1000 Words

Curator Conversations

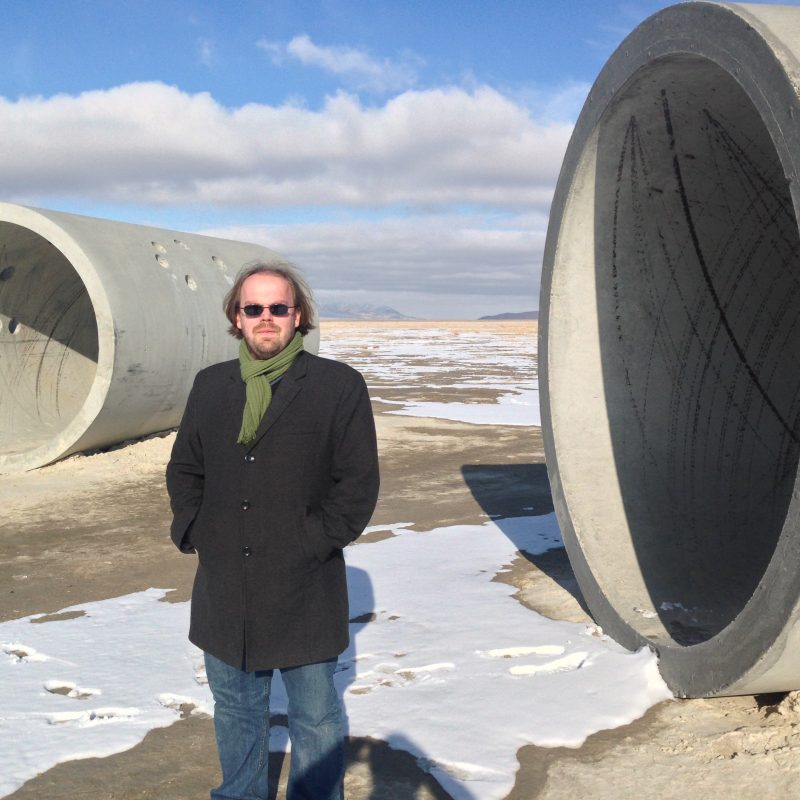

#1 Duncan Wooldridge

Duncan Wooldridge is an artist, writer and curator, and is the Course Director for the BA (Hons) Fine Art Photography at Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London. He is the curator of the exhibitions Anti-Photography (2011, Focal Point Gallery), John Hilliard: Not Black and White (2014, Richard Saltoun) and Moving The Image: Photography and its Actions (2019, Camberwell Space, as part of Peckham 24). He is working on an exhibition around photographic abstraction in the contexts of mechanical and industrial production, for 2020-21.

What is it that attracts you to the exhibition form?

Exhibitions for me are like thinking made visible in space. They can be animating and generative, because you are constructing dialogues and arguments between works, where echoes and contrasts bring qualities and values into the foreground, as something you can see, sense and think through. I normally begin at that granular level – the conversation two works have with each other, before working up to the larger display. As an ensemble, groups of work construct trajectories, and show how connections are made and remade continuously. They’re inherently propositional, I think, though they remain to this day frequently used to claim a conventional historiography that says this is how it happened, especially when a single artist is shown, or when the material is historical in nature. I’m definitely seeking to propose a different history or narrative when I’m making an exhibition. That’s what draws me to it. I like to think of how the brain is sparked by the encounter of works seen together, and how the meaning of works change by the encounters they have.

As a result, when the process works as it can, the exhibition is much more than a line of objects. It becomes a dynamic four-dimensional encounter in which your concentration and senses shift gear and become more acute. It’s like Artaud’s conception of the theatre: some senses, contexts, or details are dramatically heightened, and others temporarily subside. Being inside an exhibition can be so focused, and so concentrated, that the world outside seems to be temporarily suspended. That’s not a negation, but a reset, from which something can be built: if it holds any subsequent weight or urgency, an exhibition will subtly continue into your other encounters thereafter. Our return to the world from inside the exhibition might allow us to see and feel that it can be remade and rethought.

I realised early on in my studies that I was equally interested in the works of other artists as I was interested in making things myself. I’ve always liked this as a balance, to be neither fully the maker, the I, nor fully subservient, the classical curator/carer, occupying the supposedly neutral third person role who disappears. I am an active interpreter of the work I bring into the exhibition, but I have neither full control over the meanings, nor am I absent from their construction. When I curated an exhibition of John Hilliard for Richard Saltoun Gallery in 2014 (John Hilliard: Not Black and White) and the parallel book we made with Ridinghouse, it was to cut through John’s practice and see it a specific way with him, to read his work with my eyes, and to compare what it meant from both of our perspectives. I’ve realised since that it’s still a relatively rare model, to have an active curator of an artist with a solo presentation – I found it very illuminating, with a friction that was productive. I’d like to work more with artists like this.

What does it mean to be a curator in an age of image and information excess?

I feels like this goes very much against the ongoing narrative, that of democratic photographies or the positivism about recording our lives and our sharing economies, but I feel that the curator is meant to be demanding. And I think they should demand more of images. Our image world is so passive: most of the language about agency and participation in our work and life is a rhetorical cover, a smoke screen, for how we produce information, and for the dominant economics of our time, which currently is finance capital and advertising. To cite Sherry Turkle, we are alone together. We are producing images and we are consuming them. We are not interacting through them, at least not as we might be.

The widespread adoption of the word curator – curators pants (trousers), curated lists, and a whole lot more, a long and growing comedic list – we really should understand as an attack on careful selection, an attack on deep engagement, and a negation of specialisation, rigorous knowledge and perhaps expertise. Its comedy masks it, but it is an attack. I am not going to argue that the curator is special (we have seen of course that curators can and do maintain bias and reproduce existing relations of being subject to power), but I would have to say that the trend for curating everything is the banalisation of what can and should be a slower process of thoughtful choice. We aren’t using ‘curating’ in all of these contexts as something passionately laboured or specialised, are we? Curated pants aren’t really the best, and curators coffee isn’t any more considered, not before, not during and not after.

This is where it is directly tied to our information and image excess, to more than a rant about capital: because, like the coffee or the other commodities, we’re all hurrying to make ever more images, we’re making more and looking at more, but we’re also looking with less detail, broadcasting with less filtering, and looking with less time or expectation. The curator used to see more art than most people, but today, I wouldn’t set that as a benchmark. The curator who only wants to scan the room, or know about the new work is accelerating the process, and doing the same thing. They’re participating in what Byung Chul-Han has called the Burnout Society. Instead, the question should be, who gives work the most time? I often say that I am only occasionally a curator, and I think in the current moment, few of us are curators very often: we’re rarely given the time, or take the time, to be. Colleagues working in public institutions, who have job roles as curators, spend the majority of their time in administration, in fundraising, in organisational tasks. Curating would be a fraction of their time right now. The temptation is for this to take less time, to be more decisive, and to go with the flow of endless production, but I think a curator who is really committed to this activity will instead slow things down, and take the time to develop understanding. Being a curator is something that anyone could do, but I’d want to propose that to curate, after its original meaning, to care, is to take images and artworks outside of that cycle, and to give them an attention over long durations.

What is the most invaluable skill required for a curator?

Patience, especially in the light of the last question.

In my experience, I can also say that I think the capacity to solve problems is a recurring skill you have to put to work. Logistically, if you don’t have an endless budget but you are ambitious, you’re going to face challenges about how to get works from distant locations to the site of your exhibition, and you’re going to have to make decisions about how the show changes as a result of its contexts. I think the biggest budget I ever had for collecting works was for the Anti-Photography show I curated at Focal Point Gallery in 2011, where we had the budget for one collection of works in Europe, though we had new works arriving from the West Coast of the US, and works from several European cities. I enjoy that kind of working things out. It’s about knowing which compromises are acceptable and which ones have a serious effect, about knowing what you can solve, and who you can work with to make things happen.

What was your route into curating?

I encountered the process of exhibition making really in Norwich at the Norwich Gallery, where I volunteered for a couple of years, working on the great East International exhibitions, and some of their other shows. I would volunteer in the summer and autumn during my studies. Lynda Morris was there and her exhibition programme had many great connections to conversations in the artworld. I think that was where I learnt to find inventive ways around making exhibitions happen: for East they would just drive a van into Europe to go and collect everything! I remember the detail and care in preparing spaces, for example repeatedly painting and sanding a wall for a Sol Lewitt wall drawing, calling artists and arranging the collection and return of their works; the politeness and friendliness, and the ways of doing things. Andrew Hunt was there at that time too as an Assistant Curator, and he was a great, encouraging voice: ultimately our good relationship led to my first major curatorial project. Around that time I studied Photography at the Royal College of Art, and that equipped me to have a critical voice, to feel that as an artist you could participate in the discourse – you could and should make exhibitions as an artist, you could and should write and produce criticism too. When I was studying there, I was working at the Serpentine Gallery, invigilating, working front of house and handling limited editions, and so all of those different inputs gave me a rounded idea of making exhibitions and what they involved. At the beginning of a show, you’d sometimes get a tour from the artist (though not always), but you would, every time, get a walkaround where you’d be shown what was fragile, what was dangerous, how things were made, which works had high insurance values, all of the practical hidden details. It was a hidden education.

As I said, Andy Hunt gave me the first opportunity to curate a major show. I was working in my Serpentine job when I saw him again one day. I remember he asked what I was working on, and I told him about a show I was planning, called Anti-Photography. I was applying for a curatorial open call that Hayward Gallery had made. I remember that he said ‘that sounds a lot like our programme’, and told me to get in touch if the open call didn’t happen. It didn’t, and I went back to him. I think a key thing at that point wasn’t that I was an artist or a curator, but that I had a strong investment in the work of other artists, that I was developing ideas, regardless of whether the opportunity was there or not.

What is the most memorable exhibition that you’ve visited?

I don’t know if I can narrow this down, but I’ll try. I would like to say Rei Naito’s work Matrix in Ryue Nishizawa’s Teshima Art Museum, the single best installation of a single artwork I’ve ever seen. But perhaps that’s not an exhibition – it’s a permanent environment. I think it would have to be the 20th century collection displays called The Making of Modern Art, at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, which were specially curated by artist Goran Đorđević – Đorđević has however hidden himself under an alias of an institution of his own making, The Museum of American Art in Berlin (he is known as a ‘former artist’ who would make lectures as Walter Benjamin and making Piet Mondrian paintings with contemporary dates). Using a combination of works in the museum collection and copies, Đorđević quizzes and challenges the 20th century art museum, it’s construction of value, it’s definitions of art, and its appropriation of objects across historical and geographic contexts. Rather than just talking about it, this display actually does it, dares to put artworks in new circumstances to see what happens. Each room proposes a problem – how objects gain and lose and the name of art, how collections are formed, and how the cultural politics of the 20th century drive us towards certain relationships to culture. It ends in a proposed cultural reversal, where artworks from the western ‘canon’ are taking out of a white cube and placed into a room of controlled lighting and museum cabinets that are familiar to any viewer who has seen how artefacts are displayed in the Far East, in wall-lined vitrines and wooden display cases behind glass. This is only a proposition of course, but it reveals the commodity status of the artwork and the spaces it has depended upon. The museum commissioned the display and opened it in 2017, and it’s due to stay open until the beginning of 2021. I’ve been twice and will try and go again.

What constitutes curatorial responsibility in the context within which you work?

I think all cultural producers share a responsibility, I’d begin there. That responsibility begins fundamentally with looking at and thinking critically about the world, to work in response to that, to act to improve the world, not necessarily by making things which are political, but by thinking and understanding the ecologies in which we all operate, and provide models or gestures, perceptions and sensations that generate cultural progress before and sometimes against economic progress.

Isabelle Stengers has a great way of describing ecology when she describes it as thinking and acting par le milieu: a milieu, she reminds us, is something that can only be understood by a combination of the through and the around, and I think this describes what a curator should be doing whatever their subject or their context or their method. To think through and around is to think beyond oneself and to think of the context we and our cultural production belongs to. In my mind, I’ve linked Stengers par le milieu to Édouard Glissant’s mondialité, his modification of universality. In mondialité, you can’t remain at the abstract generalisation of universality – simply saying that it applies a priori to all, you have to see what it does in the world. It’s to try and think the world, but to also deal with the specifics, thought put into action. And so, for me, this connects us to thinking through and around, and to think about the exhibition and its consequence. We don’t talk about the consequence of an artwork or an exhibition often enough, we treat it like it just is or was. It’s not enough to go to an exhibition and leave again. What stays with us? What might it allow us to do? How do we react and in what way? Are we put on the defensive or made to feel overwhelmed, or enabled to think that we can have some kind of impact? What enables us to do this?

Deleuze and Guattari in their writing in Capitalism and Schizophrenia argued for the importance of what they called the micropolitical, even before we talked of micro-aggressions. Micropolitics is the politics contained in each and every action, the underlying politics of our interactions with each other. I think that especially relates to the present epoch, the age of self-interest and atomisation that characterised our society before we reached the coronavirus pandemic. It’s easy to say we are radical and forward thinking when public facing, or working into the macro-political realm. What, in our actions or in the consequences of what we produce, makes this manifest in each interaction? How do we work to support people or work to resist the logics of self-interest? Hopefully, on the other side, we might have learnt to think through and around.

What is the one myth that you would like to dispel around being a curator?

I think I’d like to dispel the notion that being a curator places you at the centre, that being a curator, or being an artist for that matter, puts you in the middle of the art or photography worlds. I think this is behind the fashion for curating everything. We appear to have a model that places creators and producers in the centre, which radiates out, which perhaps includes artists and curators, and then collectors and gallerists and critics and then students and audiences. I think we should be really critical of this model and its hierarchies. If you believe as a maker or producer that you are at the centre, then you are replicating an exclusive model of culture, based on outdated ideas of artistic production, propped up by money as something which limits access to many, and permits easy access to others. We must differentiate centrality from criticality, and privilege the idea of being both rigorous and generous over a desire to be the centre of attention. We should establish our own sets of values, and make them clear. Thankfully, there a number of people working within this culture who are both deeply knowledgeable and generous, and as a result, in some cases, those individuals become great connectors and facilitators. But you’d have to have your head in the sand to not see that there are plenty of people who direct everything, even indirectly, to themselves or their gain. They are maintaining the claim that culture circles around them, whether it structurally does or doesn’t. They’re both parts of the same problem.

What advice would you give to aspiring curators?

Jean Baudrillard wrote an exceptionally beautiful book that is lesser known than his writings on simulations and the conditions of Postmodernity. It’s called The Agony of Power. In it, he says that the biggest question of all is what you do with the power that you have, however small or big it is, however much it might come to be. So my advice is this: be generous. Be generous with your time, with your attention, with your labour and efforts, and with your own power to impact others. ♦

Further interviews in the Curator Conversations series can be read here.

—

Curator Conversations is part of a collaborative set of activities on photography curation and scholarship initiated by Tim Clark (1000 Words and The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University), Christopher Stewart (London College of Communication, University of the Arts London) and Esther Teichmann (Royal College of Art) that has included the symposium, Encounters: Photography and Curation, in 2018 and a ten week course, Photography and Curation, hosted by The Photographers’ Gallery, London in 2018-19.

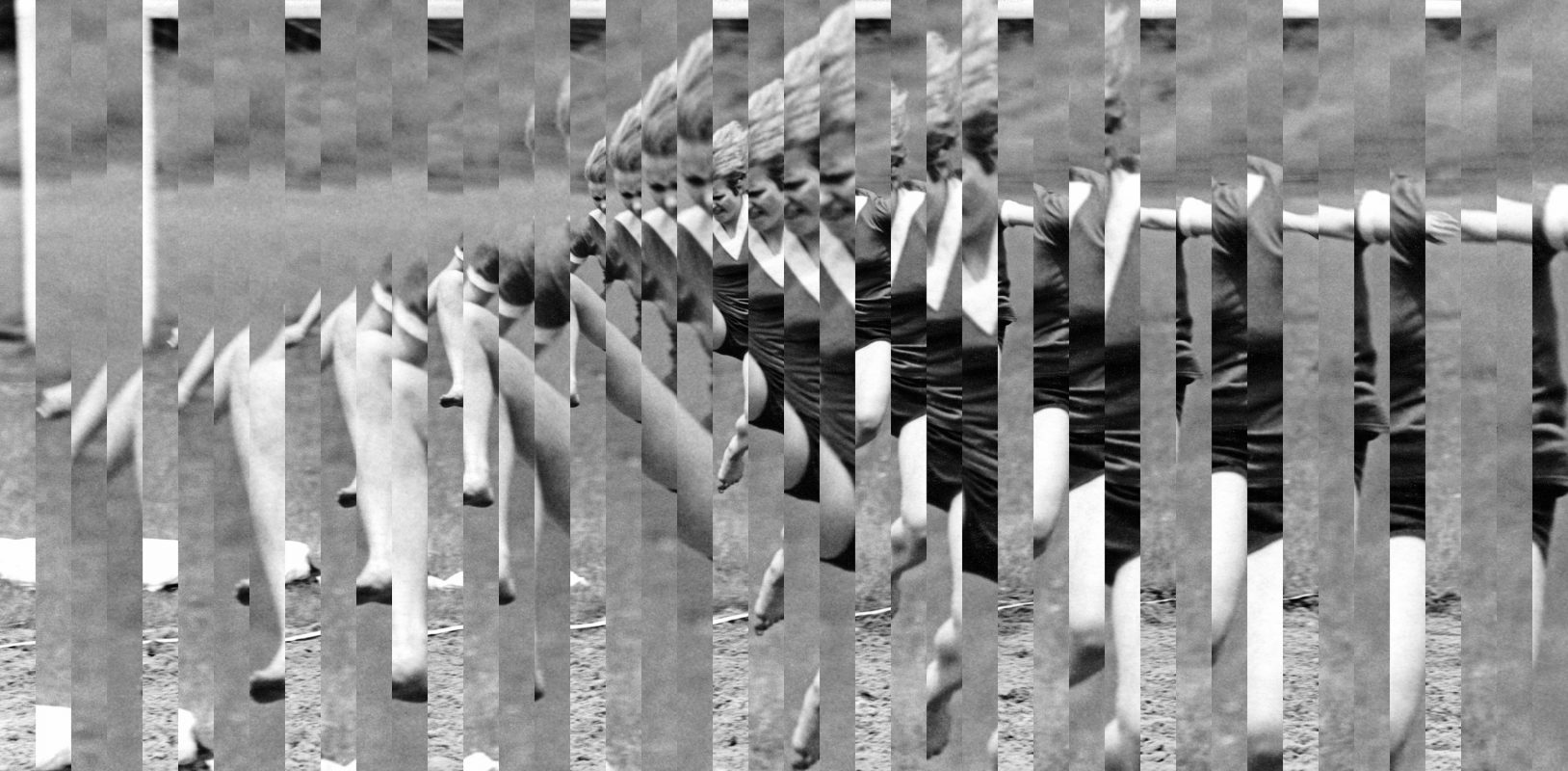

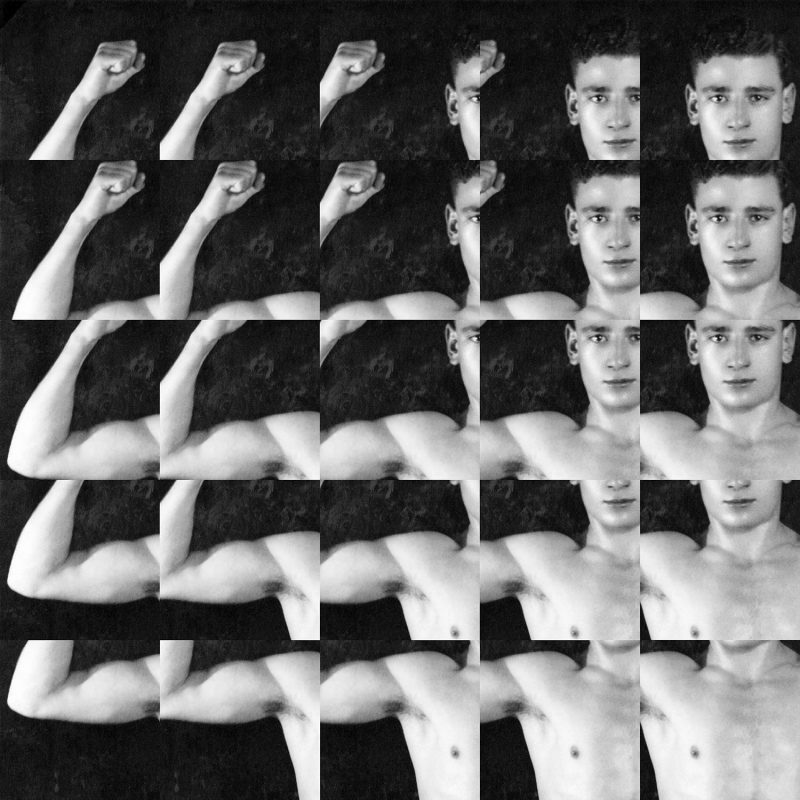

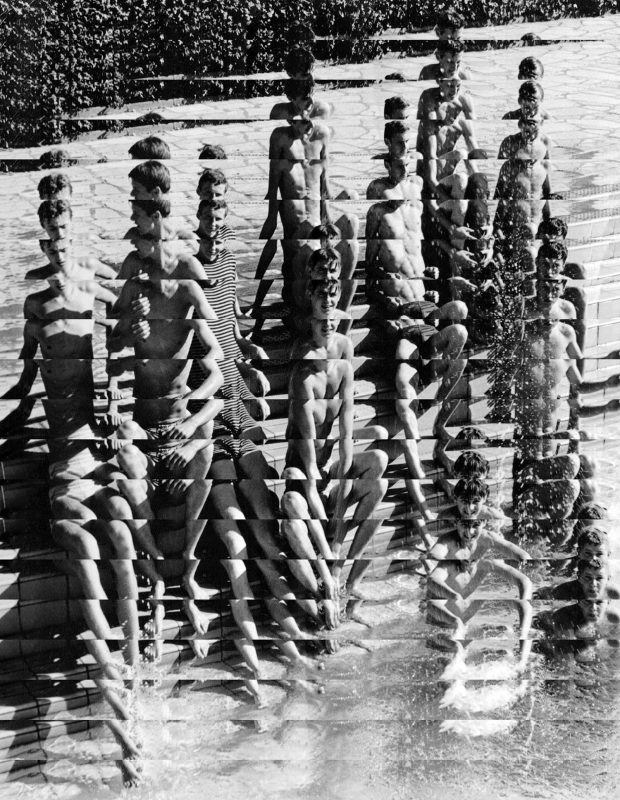

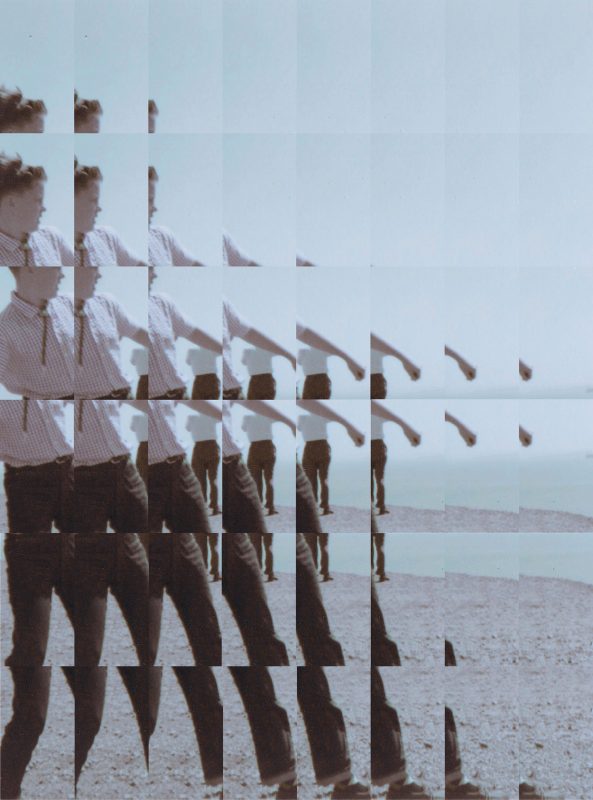

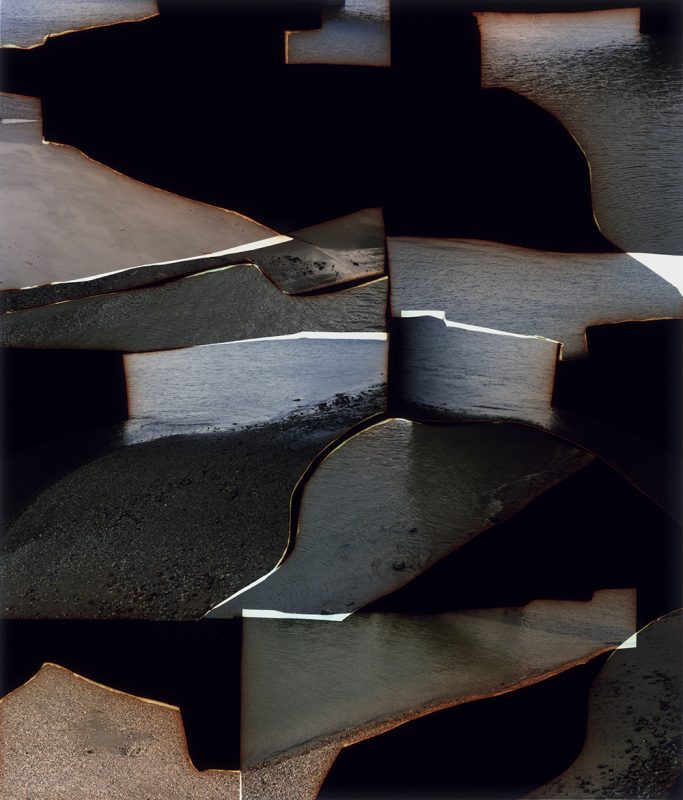

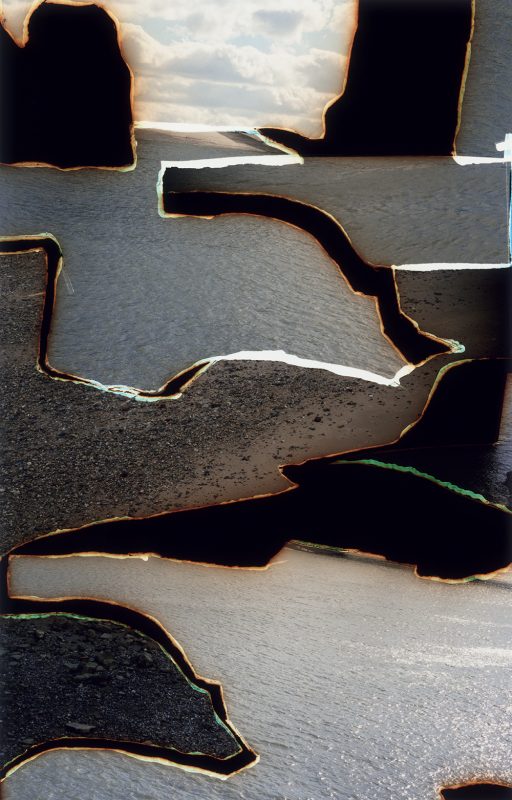

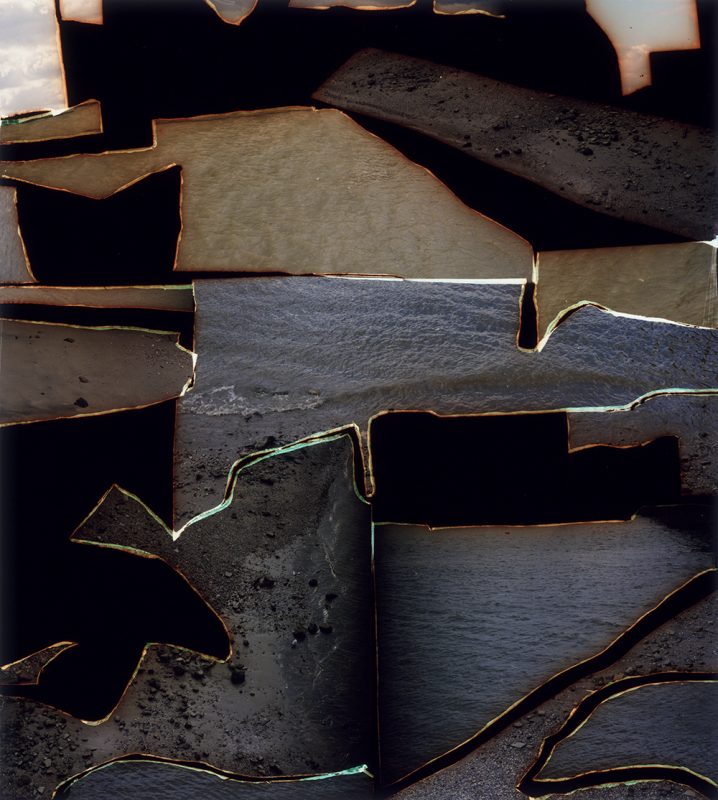

Images:

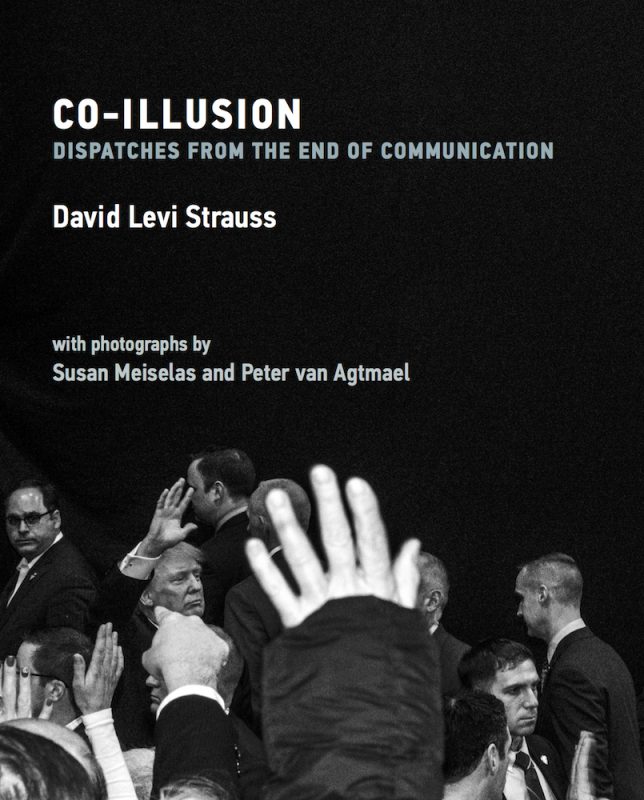

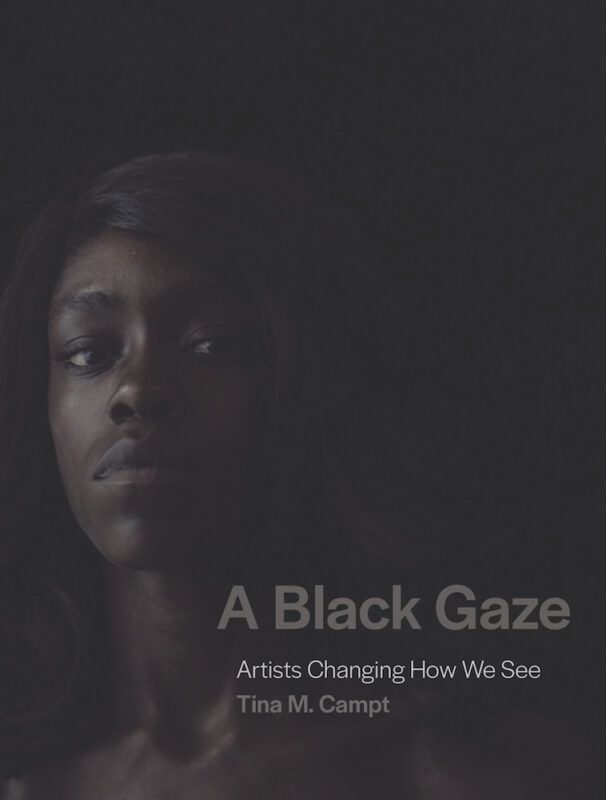

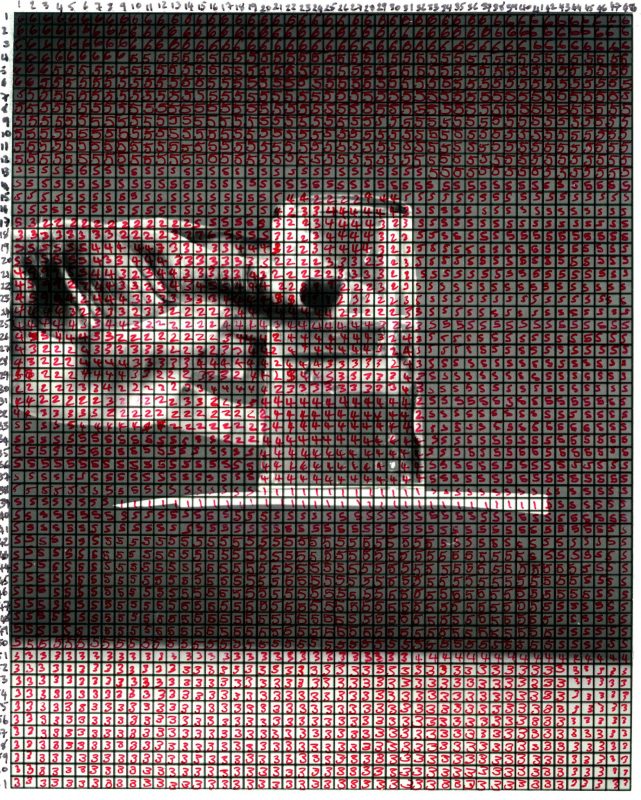

1-Duncan Wooldridge

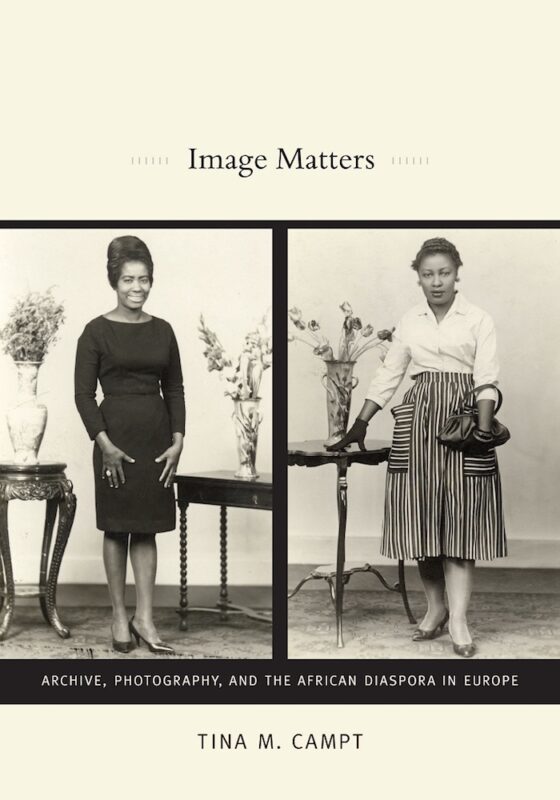

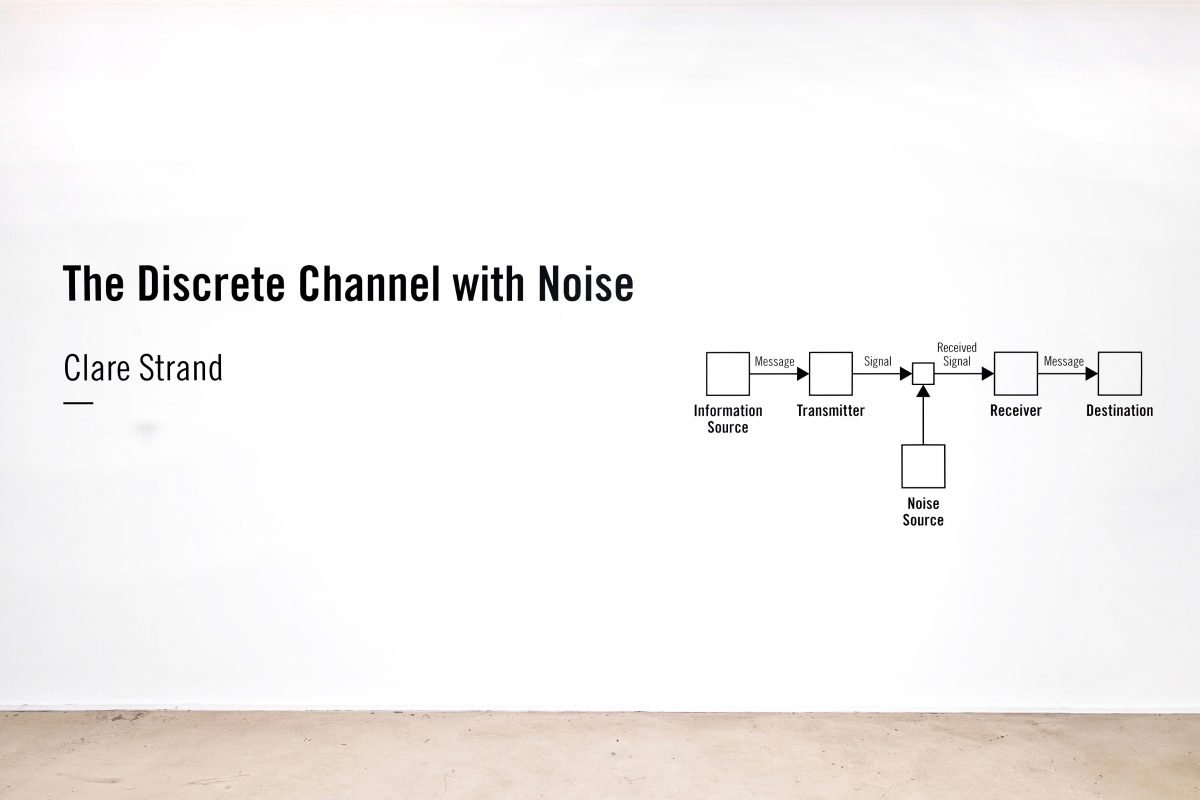

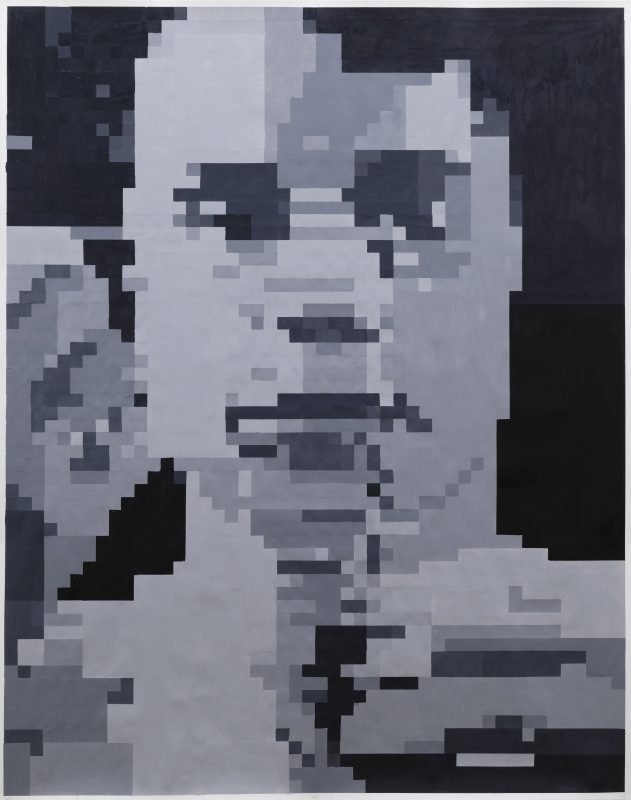

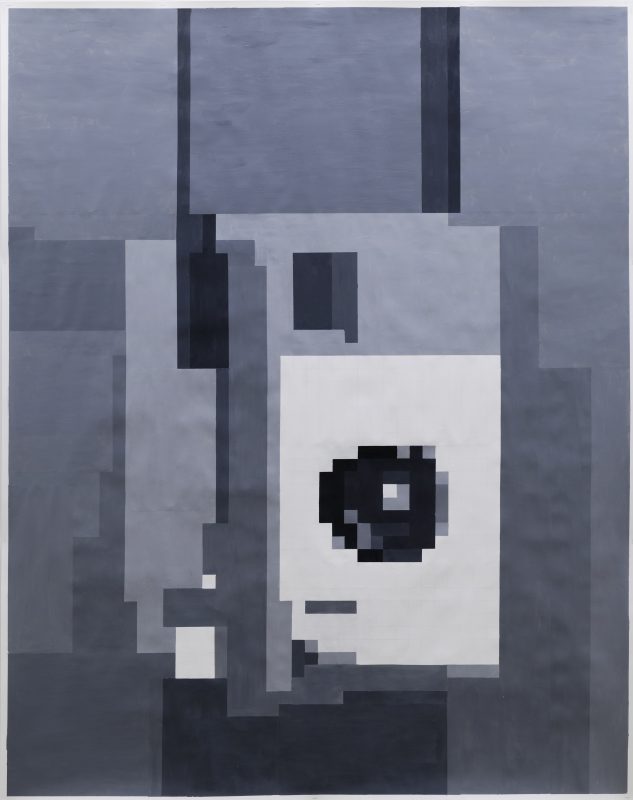

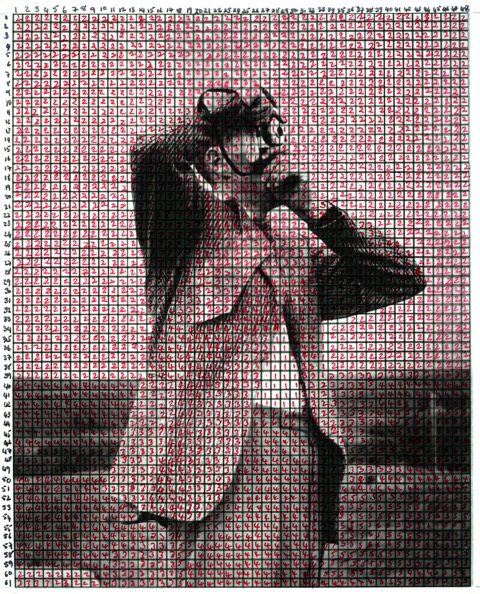

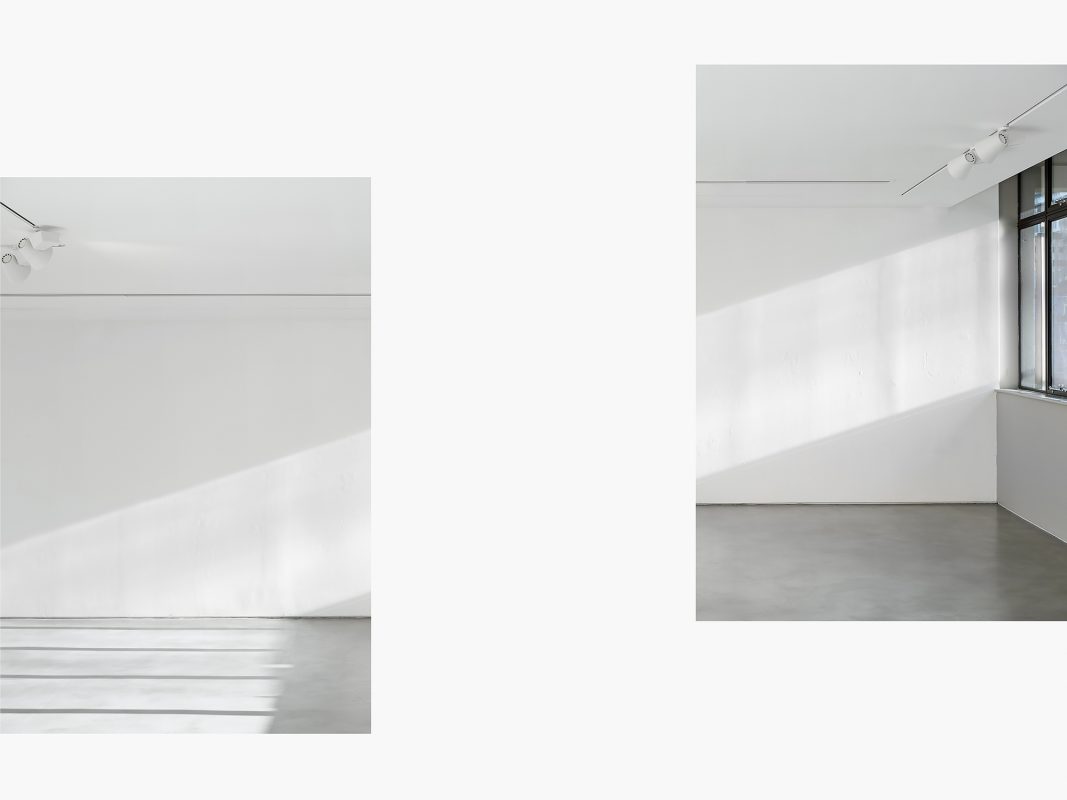

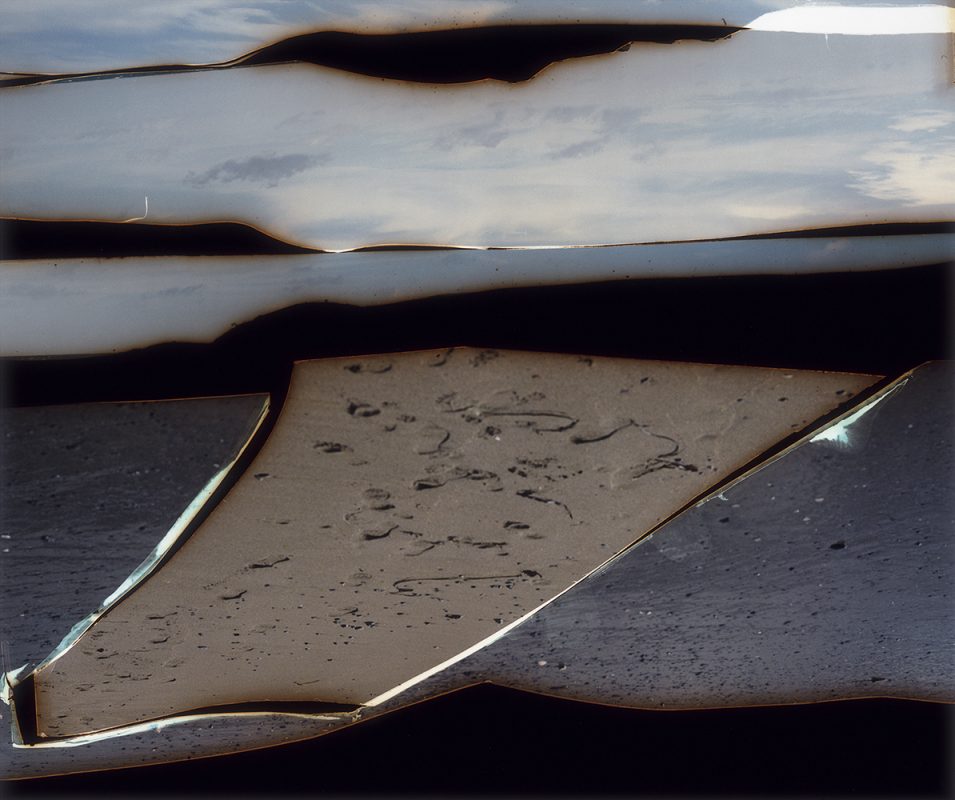

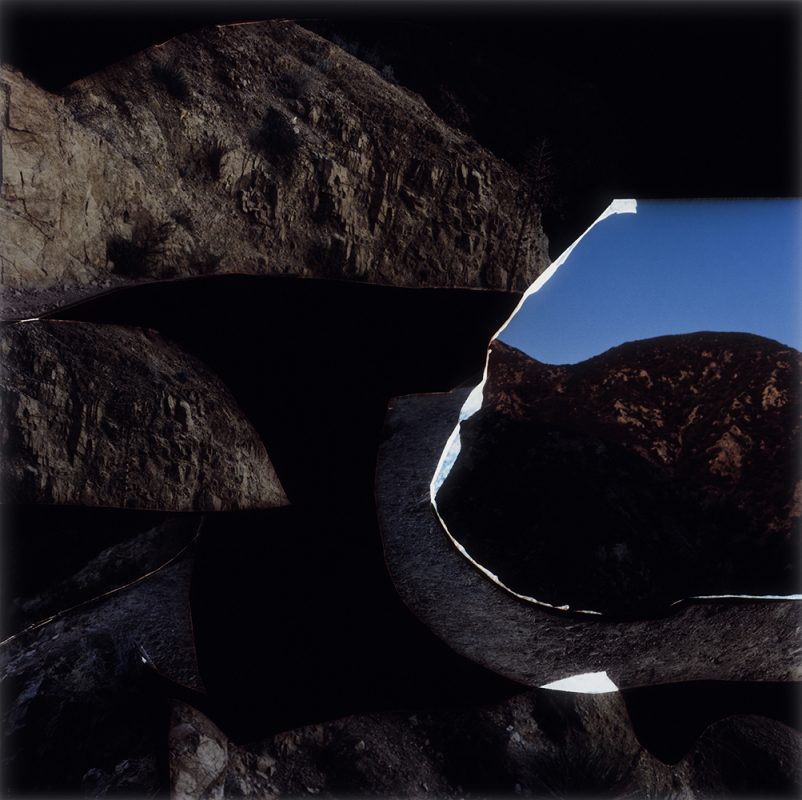

2-View of the exhibition Moving The Image: Photography and its Actions, Camberwell Space, as part of Peckham 24, 2019.

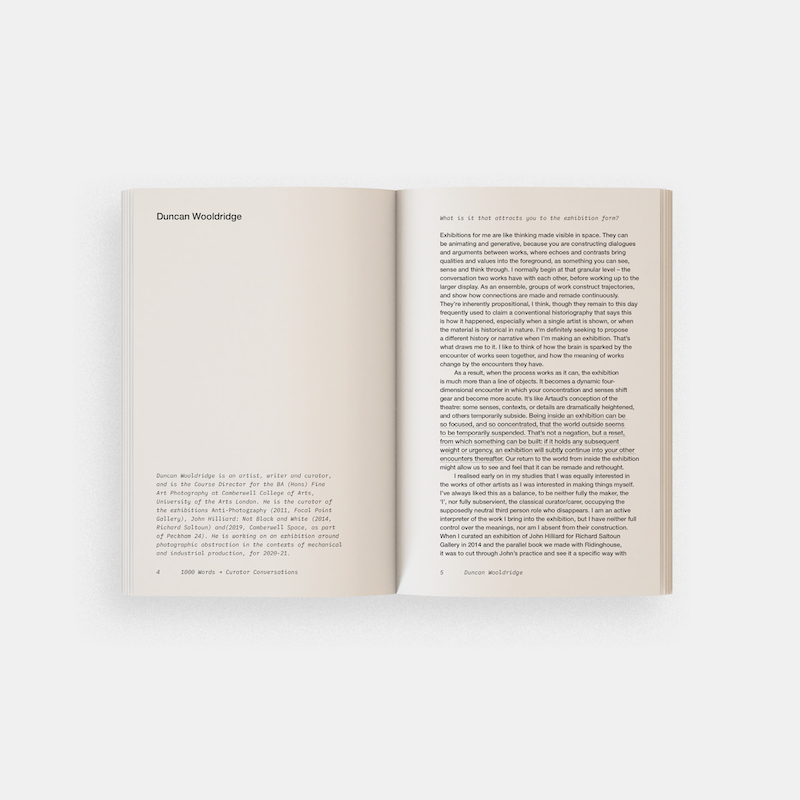

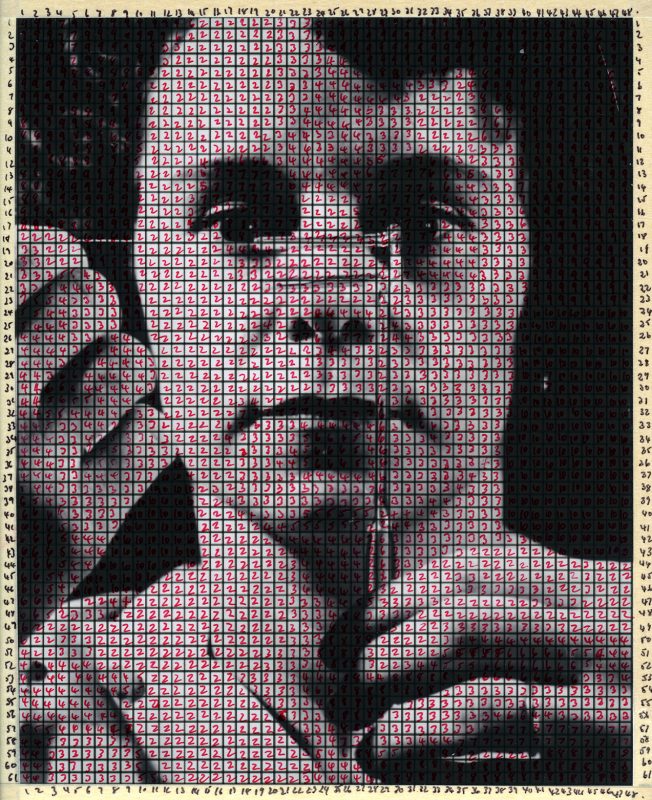

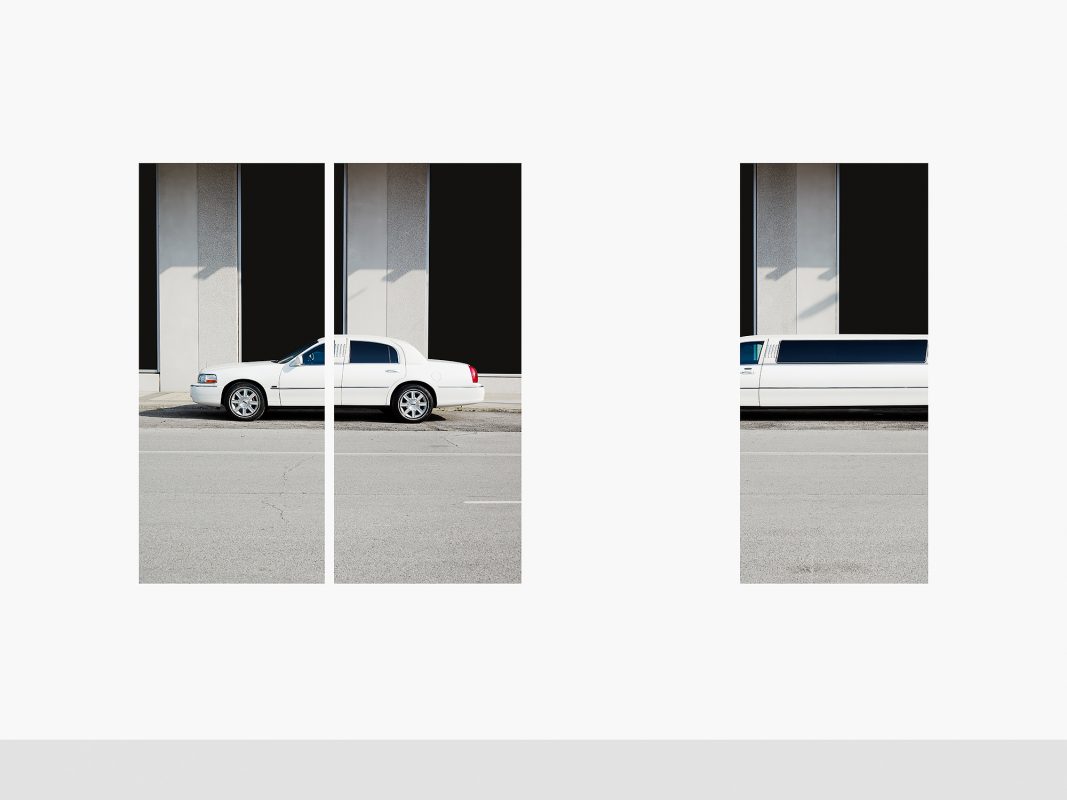

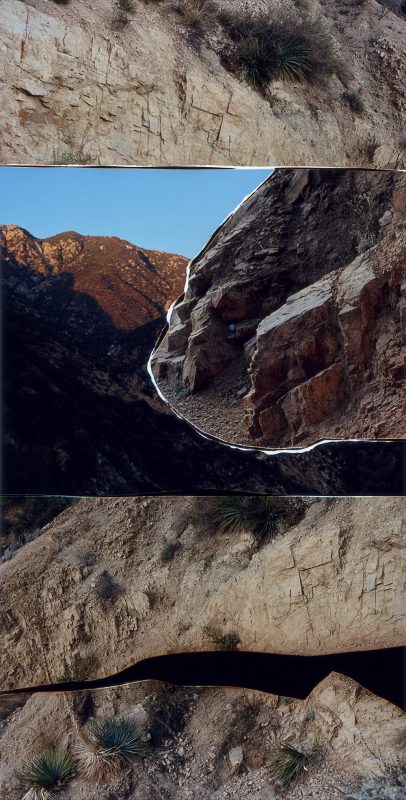

3-View of the exhibition Moving The Image: Photography and its Actions, Camberwell Space, as part of Peckham 24, 2019.