Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2020

False signals and white regimes: an award in need of decolonisation

Editorial | Tim Clark

Tim Clark on Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize’s reproduction of structural inequality, Mohamed Bourouissa’s ambivalent ‘victory’ and the implications for curatorial responsibility

Algerian-born artist Mohamed Bourouissa has been announced as the winner of the £30,000 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2020, an award founded in 1996 by The Photographers’ Gallery, London and now in its twenty-fourth year.* Bourouissa was among a shortlist of four artists that included Clare Strand, Anton Kusters and Mark Neville, having been nominated for his mighty impressive exhibition Free Trade first staged within Monoprix at Les Rencontres d’Arles 2019.

Free Trade was a survey showcasing fifteen years of Bourouissa’s creative output. His work examines the value and visibility of marginalised and economically bereft members of society, as well as productions of knowledge, exchange and structures of power. Video, painting, sculpture, installation and, of course, photography are routinely put to powerful use. So too is an impressive range of imagery that encompasses staged scenes, surveillance footage and even stolen smartphones. Ideas come into focus and vibrate against one another, laying bare some of the terrible realities and injustices of late capitalism, all the while questioning the means of an image and politics of representing the ‘other’. It felt sharp, sobering, confounding, mysterious, critical and intelligible on its own political terms. In the context of the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize display here in an extended run at The Photographers’ Gallery, Free Trade has been very capably distilled into a satisfying-enough iteration of the work, despite the typical space restrictions and challenges of staging this annual group show.

Nevertheless Bourouissa’s ‘victory’ betrays an alarming fact: he is just one of four artists of colour to win this highly-coveted prize during its twenty-four year history, joining Shirana Shabazi (2002), Walid Raad (2007) and Luke Willis Thompson (2018) who have come before him.** In tandem with this disturbing revelation we must also consider another uncomfortable truth: no black artist has ever won the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize as it approaches its first quarter of a century in existence.

What this amounts to is curatorial malpractice on the one hand, and capitalist oppression on the other – a form of reproducing and perpetuating racial inequality, both in material and ideological terms. A quick, top-level calculation of the monies awarded to just the winners alone (these figures exclude the smaller sums given to runners up) shows that a total of £485,000 has been awarded to white artists (82%), in comparison to £105,000 awarded to artists of colour (18%) – a wildly unequal distribution. Not only this, but it subsequently impacts on the discrepancies in levels of press coverage received, as well as interest from galleries, museums and collectors with implications for their markets and price points of artworks. Clearly no honest observer can say that such devaluation, in every sense of the word, isn’t a problem. And it’s a white problem that needs to be urgently addressed going forward.

It may also come as no surprise then, but is still nonetheless shocking, that the five members of the jury for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2020 – including a non-voting chair – are all white.*** However highly-respected and accomplished they may be as artists, editors and curators, this too is shameful and inexcusable. Regardless of this year’s outcome.

Whitewashing on the part of the establishment is obviously harmful to our profession, and therefore to society and culture at large. In effect it’s sending out the message to young artists and curators of colour that ‘there are no opportunities for you and your chance of attaining this level of recognition are slim – there is no space for you, and your work is not valid within the narrow parameters of this prize’. It makes it seem like a rigged system, blocking the development of black and brown excellence, while depriving us all of richness of the contemporary photographic landscape we deserve. Indeed that’s precisely how the whiteness project manifests itself over and over again. For this is a continuum, not an isolated incident. We know that as a ruling principle whiteness is most effective when it is unnamed and unseen, an idea that is consolidated by upholding status privilege while neglecting other non-hegemonic modes of being in the world, thereby reasserting itself and the normalisation of its proponents’ limited worldview. But it’s detected here in the case of the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, an award in need of decolonisation despite last night’s seemingly positive result. Only then can we begin to generate the right conditions for a level playing field.

We might think of one of Stedelijk Museum’s newly appointed Curator-at-Large, Yvette Mutumba’s conception of the task of decolonisation and what it entails. In her recent interview on frieze.com she commented: “It means understanding that decolonization is not a matter of ‘us’ and ‘them’, but concerns all of us. It means acknowledging that this is not a current moment or trend. It means recognizing that BIPoC/BAME/POC are not necessarily particularly ‘political’: we simply do not have the choice to not be political. It means admitting that having grown up in a racist structure is no excuse.”

Of course we all need to check ourselves, and what we’re doing in order to be mindful of our own privilege and positionality. It has obviously occurred to me that as a cis white man mine is a voice that certainly doesn’t need liberation but we can’t just sit and wait for change to come. I am also aware many people who look and sound like me don’t speak at all – let alone take action – lest they might ‘fail’. A perennial double bind. This is something the photographer and writer Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa reminded his audience during an ‘in conversation’ with Sunil Shah early on in lockdown, as part of Atelier NŌUA’s Once Upon a Time talks series, in which he summoned Samuel Beckett’s sage words: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better.” It’s worth noting that Wolukau-Wanambwa also shared his more general observation relating to the false consciousness that somehow, by default, those working in the arts, given that they are creative with a proclivity to ‘openness’, are not thought of – or think of themselves – as adopting racist and discriminatory practices.

At a minimum it would certainly give some meaning to the countless statements of solidarity that accompanied black squares during Instagram’s #BlackOutTuesday, not to mention the performative allyship that ensued, manifesting in platitudes such as “we must fight systemic racism” or “don’t stay silent” only to never hear from such people again on the matter or see any changes in their respective programmes and activities. Now is the time for white people who are genuinely taking on anti-racism work to attend to what we say and do. The comments from Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race (2017) author Reni Eddo-Lodge in an interview with Krishnan Guru-Murthy on Channel 4 continue to orbit my imagination: “those annoying white liberals, who luxuriate in passivity as it’s not directly affecting them. They are like, ‘I support this and want everyone to do well but I’m not going to do anything.’” In short, it is a matter of deciding to use white privilege to end white privilege.

Of course, there exists no absolution. All white people run the risk of “the danger of good intentions” as Barbara Applebaum has articulated it in Being White, Being Good: White Complicity, White Moral Responsibility and Social Justice Pedagogy (2010). We must though “foster an attitude of vigilance”, in the words of bell hooks. Turner Prize-winning artist Tai Shani reminds us of this in Why Art Workers Must Demand the Impossible on artreview.com: “The bewildering ethical paradoxes of the artworld have become as much part of the artworld as art itself. These paradoxes have been sustained by a façade of equilibrium, of a liberal centrist political position that has been hardwired into the operational models of galleries, museums, institutions, art schools, and art organisations.”

For my part, it would be particularly remiss not to name these issues in light that I led the first Photography and Curation ten-week course at The Photographers’ Gallery in 2018-19 on the invitation of and in collaboration with London College of Communication, University of the Arts London. This public course examined the various ways curating can shape our encounter with and the understanding of the photographic image. Participants were exposed to various key philosophical insights – from defining what an exhibition or curator is to future practices in the era of the networked image – as well as practical insights relating to the constantly evolving display, organisation and public dissemination of photographs. At its core lay the fundamental question of what constitutes curatorial responsibility?, drawing on Maura Reilly’s Curatorial Activism: Towards An Ethics of Curating (2018) as the key reading, in which Reilly encourages us to not only listen to others but ourselves: “What are my biases? Am I excluding large constituencies of people in my selections?; Have I favoured male artists over female, white over black – if so, why?”

I’m therefore duty bound, since evidently black and brown colleagues have bore this burden for too long, which by all accounts is exhausting and dispiriting. Halting this long-standing pattern of suppression should be all of our project. I’m aligned with Holland Cotter’s piece Museums Are Finally Taking A Stand. But Can They Find Their Footing? written on nytimes.com this June: “…which raises the question of why is it left to a black-identified institution to address the matter? Because race consciousness is widely assumed to be somehow a black issue, not a white one? Even people who once believed this can see, just from watching police violence and protests on recent news, that they’re wrong.”

The collective task then, is one that partly extends beyond the reach of and even precedes The Photographers’ Gallery and Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation’s work. To a certain extent it falls to the academy of 150 nominators of which I am part – who are proffering their two selections to The Photographers’ Gallery on an annual basis every September in order to create the long-list – to properly interrogate ourselves and consider any ‘unintentional’ biases before submitting. It’s a matter of individual responsibility and institutional accountability – a single voice that must advocate for and pursue change. It therefore also begs the ‘controversial’ question: should The Photographers’ Gallery be imposing a quota to ensure equality across the genders, sexes and races? Whatever it may be, some mechanisms certainly need to be introduced in order to fight the prize’s in-built and long-upheld discrimination given hierarchies and biases are repeating very close to home. So too is a sector-wide paradigm shift required, right through from the reading lists university lecturers set their students to who specifically galleries support and represent; from the type of media coverage allotted in the art press to museums boards, directors and curators diversifying their organisation from within, all with the view to resisting, confronting and challenging these deeply-entrenched problems within our industry.

If the tragic lynching of George Floyd and countless others at the hands of the police – Breonna Taylor, Trayvon Martin, Philando Castile, Tamir Rice, Elijah McClain and Ahmaud Arbery in the US alone – has taught us anything, it is the following: “You can feel that this is different. These [Black Lives Matter] protests are not driven by empathy but by implication – ‘I am complicit and responsible therefore I must act’; this is a much more honest relationship to white supremacy and anti-black violence,” as affirmed in an ‘in conversation’ hosted by Lisson Gallery in June with the artist John Akomfrah that was led by Ekow Eshun, together with academics Tina Campt and Sadiya Hartmam.

But it is also going to take some serious soul-searching, vulnerability and ontological insecurity. As Daniel C. Blight has written in his book The Image of Whiteness: Contemporary Photography and Racialization (2019), this “means white people must work to accept that they are sutured to whiteness and that removing those stitches is a lifelong pursuit rather than a single, narcissistic point of arrival.” Blight also cites a particularly pertinent extract from George Yancy’s Black Bodies, White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race in America (2017), in which the firebrand philosopher notes that this requires “a continuous effort on the part of whites to forge new ways of seeing, knowing and being.”

In wake of this I am compelled to ask: how, in good conscience, is it possible for an Arts Council England-funded organisation of this size and stature, in a city like London which is known for its vast range of cultures, nationalities and ethnicities – those that make up our diverse communities and multiple publics – to achieve such a historically woeful lack of representation in the case of the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize? How can this feasibly be considered productive or desirable when it comes to composing a jury for arguably the most prestigious prize within our medium? Is there genuinely that little interest to engage some of the perspectives of non-white artists, writers, publishers, curators, and so on? Did the jury members not stop to question that being part of an all white jury is problematic?****

And, in any event, what sort of meaningful, or realistic, statement do the implicated institutions really expect to make on the state of photography, given that their high-profile prize is predicated on exclusion and erasure, having enabled artists of colour to be largely subjugated and therefore not granted their share of resources and funds? How can it possibly be a viewed as a legitimate history of contemporary photography, or, at the very least, a snapshot of those artists who have made significant impact on the medium during the past three decades? Why is there only, at most, one artist of colour on any given shortlist during the prize’s history? Is that all that is allowable? Is a bare minimum ever really enough? It reeks of tokenism.

The bigger question, of course, is whether The Photographers’ Gallery, under its current direction, is properly equipped to deal with the brave new world into which we have been thrust. We need cultural leaders within contemporary photography and visual culture to step up and lead the way. Those individuals that can offer long-term and enduring strategies of resistance, create solutions that will ensure equal opportunity, exposure and remuneration; and for them to harness art’s potential for change, championing work, ideas and concepts that infuse and enrich the world and the world of images. To tackle difficult issues head on – or at least back their skilled curators to do it – all the while understanding and insisting on the difference between diversity and anti-racism to avoid any institutional hypocrisy and opportunism. “In order to move into a white self-critical space beyond anti-racism,” Blight explains in his book, “whiteness must do more than make liberal gestures in the form of pro-diversity work. We must transform our comfortable denial and unwitting ignorance into something that is, in essence, new.”

Part of that new world could be a publicly funded gallery and a prize not centred on whiteness, one that takes those vitally important, other ways of being, seeing and thinking into a traditionally white institution in order to dismantle processes of marginalisation and instead collectively build an abundant space for difference to thrive. Ultimately, we need new regimes of truth that are more compatible with the present moment, similar to what Novara Media’s Co-Founder Aaron Bastani cites in Fully Automated Luxury Communism: A Manifesto (2019) as “a strategy for our times while carving out new figureheads for utopia, outlining the world as it could be and where to begin.”

With an eye to the not-too-distant future, I hope this deeply unjust cycle can be disrupted and that the prize makes amends in the forthcoming years. Let Mohamed Bourouissa’s fantastic, albeit somewhat ambivalent, ‘win’ be the start of something new. But whether or not there is an actual appetite for meaningful, positive change remains to be seen. Clearly there is much woke work to be done, curatorial correctives to take place, new support systems to be built, destructive enterprises to be divested from, uneasy conversations to be had, discomfort to sit with, spaces to give up, injustices to be called out (and acted upon), interventions to be made. And it is going to hurt.♦

—

Tim Clark is the Editor in Chief at 1000 Words, and a writer, curator and lecturer at The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University. He lives and works in London.

Images:

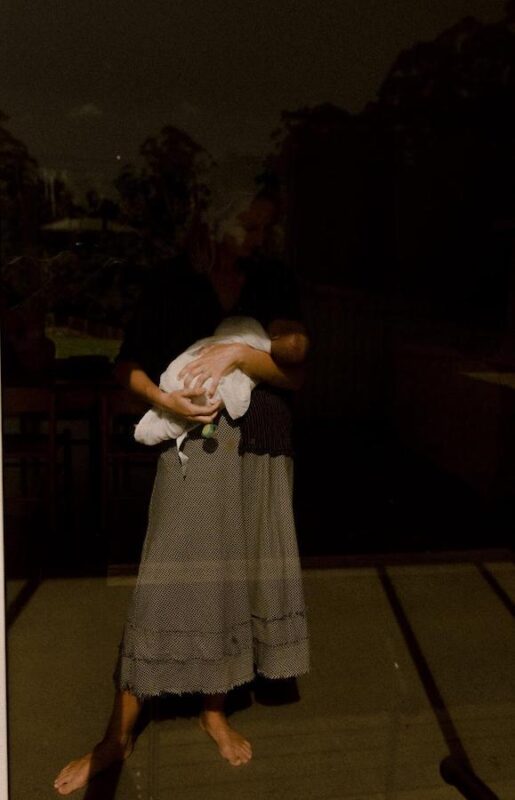

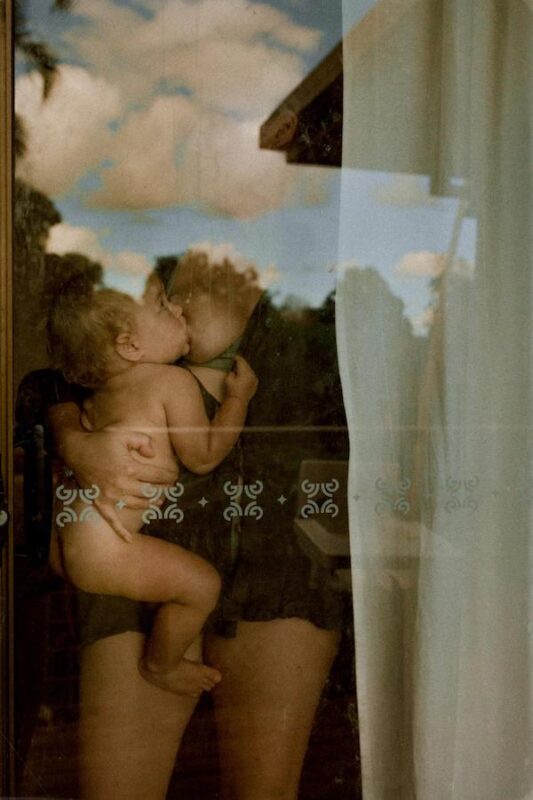

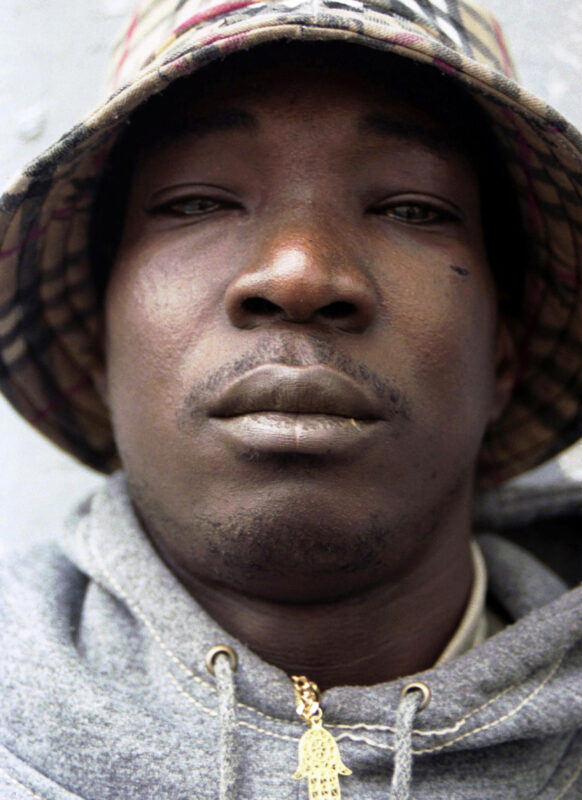

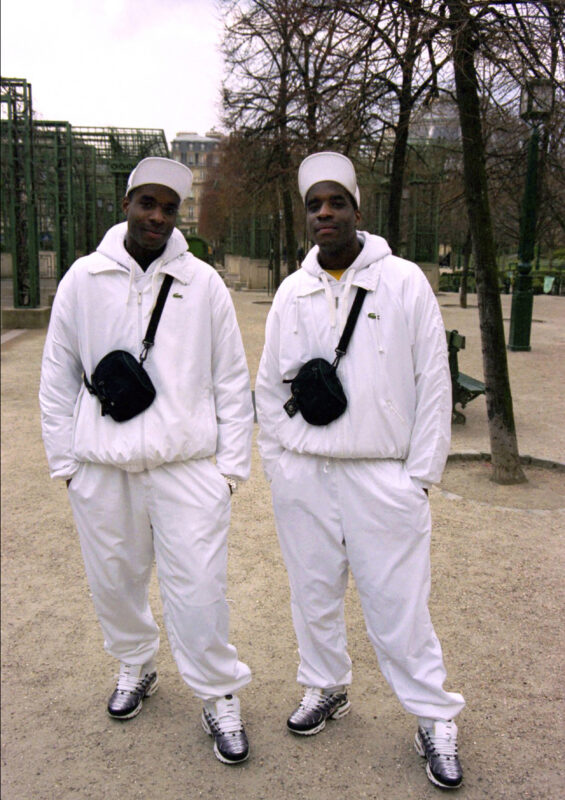

1-Mohamed Bourouissa, NOUS SOMMES HALLES, 2002-2003. In collaboration with Anoushkashoot. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Kamel Mennour, Paris & London and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles

2-Mohamed Bourouissa, Installation view. Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2020 The Photographers’ Gallery, London. © Kate Elliott and The Photographers’ Gallery

3-Mohamed Bourouissa, NOUS SOMMES HALLES, 2002-2003. In collaboration with Anoushkashoot. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Kamel Mennour, Paris & London and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles

4-Mohamed Bourouissa, Installation view. Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2020 The Photographers’ Gallery, London. © Kate Elliott and The Photographers’ Gallery

5-Mohamed Bourouissa, BLIDA 2, 2008. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Kamel Mennour, Paris & London and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles

*

Support

The Photography Prize has been realised with the support of Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation (ongoing), Deutsche Börse Group (2005-2015) and Citigroup (1996-2004).

**

Previous winners

1997 Richard Billingham £10,000

1998 Andreas Gursky £10,000

1999 Rineke Dijkstra £10,000

2000 Anna Gaskell £10,000

2001 Boris Mikhailov £15,000

2002 Shirana Shahbazi £15,000

2003 Juergen Teller £20,000

2004 Joel Sternfeld £20,000

2005 Luc Delahaye £30,000

2006 Robert Adams £30,000

2007 Walid Raed £30,000

2008 Esko Männikkö £30,000

2009 Paul Graham £30,000

2010 Sophie Ristelheuber £30,000

2011 Jim Goldberg £30,000

2012 John Stezaker £30,000

2013 Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin £30,000

2014 Richard Mosse £30,000

2015 Mikhael Subotzky & Patrick Waterhouse £30,000

2016 Trevor Paglen £30,000

2017 Dana Lixenberg £30,000

2018 Luke Willis Thompson £30,000

2019 Susan Meiselas £30,000

2020 Mohamed Bourissa £30,000

***

The 2020 Jury

The members of the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2020 were Martin Barnes, Senior Curator, Photographs, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom; Melanie Manchot, artist and photographer, based in London, United Kingdom; Joachim Naudts, Curator and Editor at FOMU Foto Museum in Antwerp, Belgium; Anne-Marie Beckmann, Director of the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation, Frankfurt a. M., Germany; and Brett Rogers, Director of The Photographers’ Gallery as the non-voting chair.

****

I am deeply ashamed to have taken part in my last all-white panel for an award as recently as February 2020. I have since turned down two other similar invitations and will ensure this never happens again.