Top 10

Photobooks of 2018

Selected by Tim Clark

An annual tribute to the most exceptional photo book releases from 2018 – selected by our Editor in Chief, Tim Clark.

In association with Spectrum.

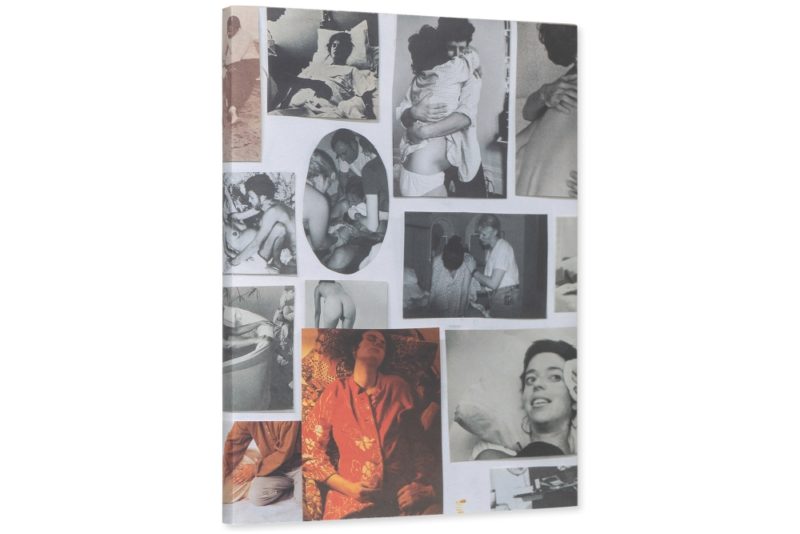

1. Carmen Winant, My Birth

Self Publish, Be Happy Editions

My Birth by Carmen Winant is perhaps this year’s standout title from Bruno Ceschel’s famed Self Publish, Be Happy enterprise. Yet it is also utterly unlike any other. Deftly fusing image and text, the book – a facsimile of the artist’s own journal – combines photographs of Winant’s mother giving birth to her three children alongside found imagery of other, anonymous women undergoing the same experience. This visual strategy aims at “the flattening of cross-generational time and feeling”, while the title is a nod to Frida Kahlo’s 1932 painting of the same name. Immediate, precarious and utterly vulnerable, Winant’s project, which coincided with an on-site installation at MoMA’s Being: New Photography 2018, is also bold and fearless. Sensitive to the world, and to the world of images, My Birth asks probing questions that move beyond transgression to open up a space for considering childbirth and its representation as a political act.

2. Zanele Muholi, Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness

Aperture Foundation

What really matters now are the needs that art answers, and visual activist Zanele Muholi always delivers with great rigour. Having first emerged as a photographic spokesperson of members of the black queer community in South Africa and beyond, her long-awaited monograph sees Muholi turn the camera on herself to powerful effect. This arresting collection of more than 90 theatrical self-portraits first reclaim and then reimagine the black subject again in ways that resist, confront and challenge complacency to racism – both historic and contemporary. During these times when violence, misogyny and even white supremacy are rife, the photographs’ accumulative presence flies in the face of stereotypes and oppressive standards of beauty.

3. Raymond Meeks, Halfstory Halflife

Chose Commune

This is the kind of pleasurable photography that approaches something so eloquent yet understated but which we cannot altogether grasp. Master of the quiet photograph, Raymond Meeks is also a prolific photo book maker. Meeks’ current collaboration with Chose Commune bears all the hallmarks of his lyrical explorations; strong narrative and occasional riffs off poetry and short fiction, all the while concentrating on the symbiotic relationship between family, memory and a sense of place. Here, black and white photographs of young men, making their way through openings in hedgerow to access prime spots for river-jumping in the Catskill mountain region of New York, are both visceral and spontaneous. Their pale bodies fling themselves into the dark void, frozen as if mid-flight, pivoting from the point of view of an adult seemingly remembering a moment of fledgling sexuality and uncertain future.

4. Michael Schmelling, Your Blues

Skinnerboox and The Ice Plant

Taken between 2013 and 2014, and shot while on commission for the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Colombia College Chicago, Michael Schmelling’s photographs in Your Blues are our guide through the city’s vibrant and eclectic music scene, where “the dominant form is hybridity”. Musicians and revellers, parties and recording studios, lovers and strangers all collide, depicted through casual views and with feelings of familiarity. This then forms a ripe photographic account of the varying degrees of individualism within this community. Blues, punk, hip hop, psychedelic jazz, emo, hardcore and house music are all part of Chicago’s cultural inheritance and encompassed here via Schmelling’s vignettes and reflections on niche and local performers in unconventional venues. Akin to a novel of images, Your Blues provides a noteworthy contribution to this year’s offerings.

5. Max Pinckers, Margins of Excess

Self-Published

A response to the ‘post-truth’ era, Max Pinckers’ speculative documentary work revolves around the narratives of six protagonists who all momentarily achieved infamy in the US only to be ousted as fakes or frauds by the media. Such highly-idiosyncratic stories range from a self-invented love story set in a Nazi concentration camp to a man compulsively hijacking trains. With fever-dream urgency, Margins of Excess brings together fragments of these lives through staged photography, archival material, interviews and press clippings: the explicit folding of imagination into imaging “in which truths, half-truths, lies, fiction or entertainment are easily interchanged.” Pinckers’ take on embracing reality in all its complexity via this particular strand of storytelling offers an interesting reminder: that contemporary documentary practice might be more productively considered as small arguments, gestures or even critical methods.

6. Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê, White Gaze

Sming Sming Books

Readers of 1000 Words will recall the recent magazine feature on this gem of a photo book from collaborative duo Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê, which deserves much wider recognition in light of its poetry, playfulness, acuity and, most crucially, decolonising strategies. Intellectually energetic, White Gaze repurposes imagery from National Geographic to confront notions of white privilege and Western-centrism by reworking and negating image and text from the publication’s original pages. Countless uncomfortable truths hidden at the bottom of every lie, every act of denial or white complicity, come to bear through the interplay of the two languages, critiquing how meaning is constructed to administer imperialist narratives and racist histories.

7. Mimi Plumb, Landfall

TBW Books

As far as great discoveries go, the case of Mimi Plumb’s resurfaced archive has been a fairly recent but major breakthrough. Having taught photography throughout much of her career at San Jose State University and San Francisco Art Institute in the US, it has only been during the past five years that her work has really come to light following the 2014 exhibition of her Pictures from the Valley series. Now, a collection of images taken throughout the 1980s have been published by TBW Books under the title, Landfall, containing black and white photographs full of foreboding and unease, yet always delicate and beautiful in register. They appear to encapsulate a time when the world at large seemed out of kilter – with obvious parallels to our present moment. Stylistically, too, there’s a whiff of Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand and Henry Wessel to these images that certainly will not fade quickly.

8. Chloe Dewe Mathews, Caspian: The Elements

Aperture Foundation and Peabody Museum Press

It’s heartening to observe this renewed period for Aperture Foundation’s photo book publishing arm, albeit still very traditional in format. One of its many great, recent titles comes courtesy of British photographer and filmmaker Chloe Dewe Mathews who spent five years roaming the borderlands of the Caspian Sea, where Asia seamlessly merges into Europe, to come away with a compelling record of the region’s complex geopolitical trevails. Much of this of course is largely bound up in the singular importance of gas and oil reserves and the disparate economies of bordering countries – Russia, Iran, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan – but it’s Mathews’ receptiveness and examination of the ties between people and the landscape, as well as the religious, artistic and therapeutic aspects of daily life, that are so intriguing.

9. Thomas Demand, The Complete Papers

MACK

While there is obviously no equivalent experience to viewing a Thomas Demand artwork at its intended size and scale, this new volume on the oeuvre of the acclaimed German artist more than makes up for it in scope, depth and scholarship. Edited by Christy Lange, and with texts from voices as diverse as the novelist Jeff Euginedes to curator Francesco Bonami, The Complete Papers provides a hugely comprehensive view of Demand’s past three decades of artistic production. Known for using pre-existing images culled from the media, routinely with political undertones, which he then recreates from cardboard and paper at 1:1 scale before photographing the assembled scene, admirers of the work will no doubt appreciate hitherto unseen pieces from the early 1990s when he first started making paper constructions for this sole purpose of photographing them. With the customary bibliography and full exhibitions listing, this is a researcher’s dream. A catalogue raisonné of the highest order.

10. Sunil Gupta, Christopher Street, 1976

Stanley/Barker

Sunil Gupta’s Christopher Street, 1976 performs an act of personal remembrance by bringing together photographs shot in in New York when the artist spent a year studying photography with Lisette Model in between cruising the city’s streets with his camera; part of a burgeoning, proud and public gay scene prior to ensuing AIDS epidemic that subsequently sent it underground. The photo book is minimally designed, presenting one black and white photograph on each right-hand page in a spiral-bound volume, marking the latest release in Stanley/Barker’s small but judicious selection of titles. It celebrates both a key moment in Gupta’s identity and the political value embedded in the struggle for LGBT liberation, the consequences of which were far-reaching. ♦

![]()

—

Tim Clark is a curator, writer and since 2008, has been Editor in Chief and Director at 1000 Words.