Posthumous collaboration

Published with Hartmann Books, Ein Dorf (A Village) 1950–2022, is a photobook by Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler in posthumous collaboration with their late family member Ludwig Schirmer. It allows the viewer to travel through time yet stay in the same place – Berka, a small village in Thuringia, Germany – where in recent days the far-right party Alternative für Deutschland (AFD) has come top in a state election. In his review, Michael Grieve writes how photography projects that collaborate with the deceased have the potential to breathe new life and recontextualise how we understand the past, the present, and project with unease into an uncertain future.

Michael Grieve | Book review | 05 Sept 2024

Serendipity can be a major creative force and harnessing its potential has the possibility to culminate into something solid and everlasting. And so it is with the modestly titled Ein Dorf (A Village) 1950–2022 published by Hartmann Books, the latest photobook project by the acclaimed German documentary photographers, Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler in posthumous collaboration with the late Ludwig Schirmer. All of them have photographed the same village at different times over a seventy year period at approximately 20 year intervals. The book is a comparative study of a specific place documented from three different perspectives over four historical periods. The story of this book is truly extraordinary, fused with many layers and chance connections that it positively feels that it was meant to come together and see the light of day. As Ute Mahler explains, the seeds of the book were sown in 2001: ‘When I discovered the pictures in my father’s estate, I was already thinking about a book. The book, At Home, with only his photographs was published in 2003. In 2019 Werner and I had the idea of taking photographs in Berka and putting all four works together.’

Ein Dorf is split into four chronological chapters; Ludwig Schirmer 1950-60, Werner Mahler 1977-78, Werner Mahler 1998 and Ute Mahler 2021-22. The ‘dorf’ in question is the small rural village of Berka, situated almost in the centre of Germany in the Thuringia district, where in recent days the far right party Alternative für Deutschland (AFD) – led by ethno-nationalist Bjorn Hocke – has come top in a state election. Thuringia is of course the place where the Nazis first won power in a German state government in 1930 before taking up the helm in Berlin three years later.

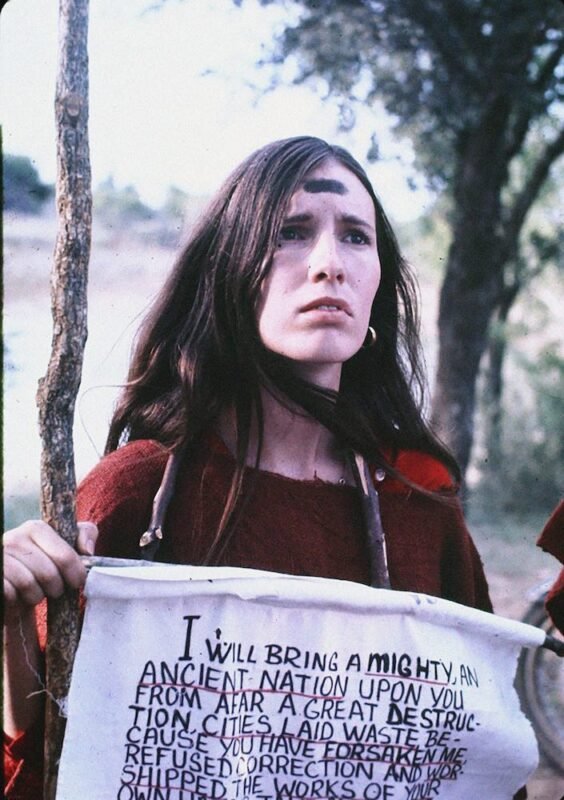

The first in this trilogy of photographers is Ludwig Schirmer who took over the family business running a mill in the village at the end of WWII. During his spare time Schirmer photographed the village over a 10 year period before moving his family to Berlin where he became a successful professional photographer. With great enthusiasm as the photographs tell, he took pictures for the most part with a medium format Primarflex 6×6 camera with great observational skill in an informal manner. His photographs are a hive of activity and always feature people, and fully embrace village life ranging from social functions and rituals to farm work, punctuated occasionally by a portrait. The slaughtering of pigs is a constant through all four projects as is the Straw Bear, a traditional character from medieval times found at carnival processions.

Photographers often used to differentiate between those with a natural or forced eye and Schirmer certainly possesses the former with an innate intuition of composing complex situations, having a measured sense of distance that is close and intimate and can only be captured with subjects who trust his presence and not question intentions. Schirmer has an unflinching visual capacity to hold still the movement and energy of the people of Berka with images that are at times reminiscent of the rural painting of Dutch Renaissance artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder, who gives credence to the peasant population surrounded in a village context, and representing groups of people and individuals as small figures engaged in their own distinct activity. Unlike the fluffy, picturesque landscape paintings of, for example, John Constable in the 18th century, Bruegel was untainted with notions of romanticism and the sublime. In hindsight Schirmer’s pictures have a certain nostalgia, but these monochrome realist expressions convey a certain frisson of engagement and are without any agenda other than celebrating the hive of activity of village life and capturing a glimpse of an even greater sense of joy now that amongst the Berka population the horror of the WWII is behind them.

After the trauma of the war, Berka found itself as part of the German Democratic Republic, under the control of a socialist system. Thus the early stages of the GDR and Schirmer’s pictures obviously reveal little evidence of the socialist system except perhaps in one intriguing image of suited men with inappropriate fine shoes for a muddy field, observing a trench made by a tractor; conjuring perhaps a narrative of state officials making decisions about productive efficiency in the new age of forced collectivism. In some of the photographs, in an almost incidental way, can be seen a little blonde haired girl who is Ute Mahler, the daughter of Ludwig Schirmer. Here the connectedness of the stories of the Ein Dorf story of one place develops an autobiographical layer of meaning. In 2003 Ute described the process of making sense of her father’s archive: ‘I found one small black and white print – an image of a young child climbing a tree. A photograph of me. Suddenly everything came rushing back – the sweet smell of spring and summer, the gentle hilly landscape, my childhood. It felt like stumbling upon a hidden treasure. The photographs were not organised in any way; there were few prints, hardly any contact sheets, and contact sheets without any negatives. Eventually the whole family pitched in to help with the daunting task of sorting through the archive. We discovered unbelievably powerful images, dreamlike in their charisma and aesthetics. For the family the images from my father were very important. But for me they touched me not only as a daughter but, above all else, as a photographer.’

The central position of Werner Mahler’s combined projects can be understood as representing a link from one place in time to another; a personal bridge and documentary divide between Ludwig Schirmer the father, to Ute Mahler the daughter, and a historical and political bridge from communism to the reunification of a divided Germany. As a young man in the 1970’s Werner Mahler was the apprentice to the then now successful commercial photographer, Ludwig Schirmer, and at this moment Werner met and fell in love with Ute and so they married. As a student of photography at the Academy of Fine Arts in Leipzig, Werner documented Berka between 1977 and 1978 for his graduate exhibition. And, despite the spectre of forced socialism, village life is still very much alive with remnants of the past but now with the added, noticeable changes of fashion as well as farm machinery albeit with continued traditions and in opposition to official government policy.

In the accompanying text to Ein Dorf, Steffen Mau, Professor of Sociology describes how at this time, ‘it was not always easy to bring an entire village into line with official policy. In Berka pigs continued to be slaughtered at home, carnival was celebrated following exotic traditions, there was music in the streets and bizarre folklore traditions were maintained. Nevertheless, anyone who opposed the party line too adamantly could expect to feel the consequences, even in a village.’ 20 years later Werner was commissioned by Stern magazine to document Berka in the context of German unification which was in the process of a turbulent transformation. Werner’s photography has sharpened with experience with a more precise eye for detail and composition. This was a period referred to as the Wende, the ‘turning’ from state socialism and a controlled economy to a democratic system with a free market economy. The difference from 20 years previously is distinct in the material effects of a consumer society. Rural character and authenticity is radically being replaced with facades from home improvement stores and cars are more visible.

The most powerful first impression of Ute Mahler’s photography is the profound sense of emptiness found in the well manicured streets of Berka. The contrast of the village from the time of her father up until today is truly startling; a microcosm of the increasing genericism of our societies and disintegration of community life. Unlike Schirmer’s joy and optimism, Ute Mahler’s project exists moving towards a vacuous impasse and asks questions, detectable in the eyes and manner of those young women she portrayed, the same age as Ute when she left Berka, as to a sense of doubt of any fruitful future. Four young girls dressed in tight jeans, tops and white trainers most probably produced in China or sweatshops in Bangladesh, India or Cambodia by girls the same age if not younger. This sounds extremely despondent and a million miles away from simple village life, though not so simple, yet we know that in almost every village today, in Europe and the UK, that the supermarket has gone some way to replace the local grocer, butcher and baker, and that the plasma screen in every living room has replaced social activity, not to mention the mobile phone. As always Ute’s portraits are photographs charged with a distinct empathy and honest distance and her subjects are never victims though undoubtedly the sense of an atomised community is clearly imbued in the tone and description of her visual representations. People seem to be there but not wholeheartedly present.

Ein Dorf opens up a portal into a hitherto and seemingly insignificant place, within which this complexity and multi-layered story reveals a wonderfully unique testament to the straight documentary genre; unpretentious, deceptively simple and grounded in a sophisticated process of showing what is ‘there’, and with this exemplary example we witness the inevitable changes of a particular society over a period of time. Time, of course, is the great force here and brings the narrative of this book together; an arbitrary photographic topography brought to reason. These pictures contain many small details for us to decipher and unravel a history of seismic proportions. Ute and Werner Mahler are without sentimentality and make no judgments, possessing a skilful ability to balance a cool and measured detachment with a warm engagement to the subject due, in part, to their personal empathetic recognition to those they photograph. Photography projects that collaborate with the deceased have the potential to breathe new life and recontextualise how we understand the past, the present and project with unease into the uncertain future. Not only is society in perpetual motion but the meaning of photographs are always constantly in a state of flux.

Sociologically Ein Dorf is a significant photobook and should be on the reading lists at all sociology and history departments at universities. The book also operates on another level which is the metaphysical, evoking memory and a melancholia of the passing of time while also revealing the urge of photography to fix that time. In his book Austerlitz, the German author W.G. Sebald, writes of the central character describing how in his photographic work he was always entranced, ‘… by the moment when the shadows of reality, so to speak, emerge out of nothing on to the exposed paper, as memories do in the middle of the night, darkening again if you try to cling to them, just like a photographic print left in the developing bath too long.’

The shadows of Ein Dorf have managed to be fixed by virtue of having been shared and the preservation of certain memories for the photographers themselves remains the enduring task of serious photography. Both collective and personal memory builds our identities and without it, as W.G. Sebald postulates ‘we would not be capable of ordering even the simplest thoughts, the most sensitive heart would lose the ability to show affection, our existence would be a mere never-ending chain of meaningless moments, and there would not be the faintest trace of a past.’ ♦

All images courtesy of the artists and Hartmann Books. © Ute Mahler, Werner Mahler, Ludwig Schirmer

Ein Dorf 1950–2022 is published by Hartmann Books.

—

Michael Grieve is a photographer, Director of ArtFotoMode, Hamburg Werkstatt Fotografie (HWF) and lecturer at Ostkreuzschule in Berlin. In 1997 he graduated from the MA Photographic Studies from the University of Westminster and then proceeded to work as a photojournalist and portrait photographer for publications internationally. He was Deputy Editor of 1000 Words and a writer for the British Journal of Photography. Since 2011 he has been Senior Lecturer at Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, Akademia Fotografie Warsaw and the University of Art and Design, Berlin, and currently teaches at Ostkreuzschule für Fotografie, Berlin. He is currently working on Procession, a project documenting the peripheral space between Athens and Elifsina, Greece.

Images:

1>3-Ludwig Schirmer, Ein Dorf, 1950-1960

4>6-Werner Mahler, Ein Dorf, 1977-78

7>9-Werner Mahler, Ein Dorf, 1998

10>12-Ute Mahler, Ein Dorf, 2021-22

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza