Top 10 (+1)

Photobooks of 2025

Selected by Tim Clark and Thomas King

As the year draws to a close, an annual tribute to some of the exceptional photobook releases from 2025 – selected by Editor in Chief, Tim Clark and Editorial Assistant, Thomas King.

1000 Words | Top 10 (+1) Photobooks of 2025 | 5 Dec 2025

Join us on Patreon

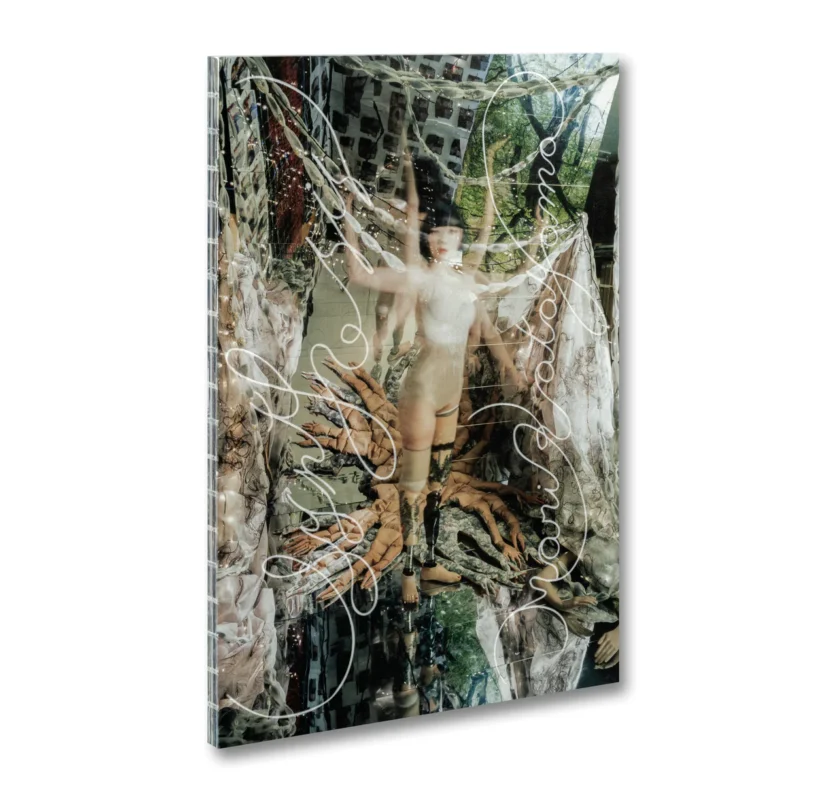

1. Mari Katayama, Synthesis

SPBH Editions

Mari Katayama gathers six years of her practice, 2019 to 2025, into an artist’s book that reads as both playful and challenging. Those familiar with Katayama’s work will recognise the materially rich choreography. Her body appears, often entwined with hand-sewn sculptures, threaded forms and collaged papers, the objects acting less as adornments than as co-actors in a carefully staged performance of the self (Katayama chose to have her legs amputated at the age of nine following a developmental condition). The book’s nine photographic series were made in Katayama’s home studio in Gunma, a conscious return to her ‘rural roots’ after years in Tokyo, during a period in which she became a mother. Yet in this turning back, she also looks forward. Synthesis is, in many respects, not a tidy catalogue but a layered fusion of self-portraiture, object-making and the living textures of experience.

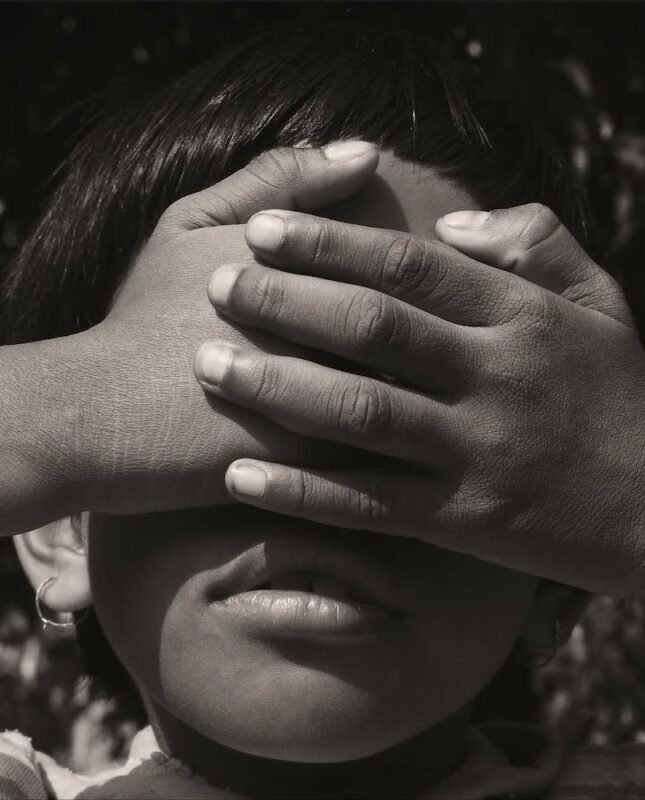

2. Phoebe Kiely, She Could See Herself In The Darkness

Witty Books

From Torino’s ever-discerning Witty Books, founded by Tommaso Parrillo, comes a vivid compendium of prints created between 2020 and 2024 by artist Phoebe Kiely. Kiely’s images interlace tight, intimate fragments of the human body, guiding the eye through surfaces, gestures and the subtle slippages between presence and absence. Following her previous book, They Were My Landscape, which explored the anonymity of people, objects and street scenes, this new work continues such investigations, deepening attention to materiality, tactility and intimacy, in which darkness holds the contours of queerness together, producing a long-awaited next-part of her photographic practice. For Kiely, bodies are never the whole story, nor is the idea of a fully realised subject; what takes precedence are parts, textures and the distances between them.

3. Daniel Lee Postaer, Mother’s Land

Deadbeat Club

China’s vertiginous transformation over the past 15 years has been devastating if not dizzying (its high speed rail network now spans over 500 cities, all constructed since 2008, is just one example of this expansion). Postaer, who lived in the country in the early 2000s and returned repeatedly in the latter decade, witnessed the country’s rapid development firsthand (his grandparents fled the communist regime there more than 50 years ago). Mother’s Land, a 15 x 11″ hardcover monograph, documents these shifts with careful eye. The demolition of old structures, the emergence of new architectures, feeling signage and spaces glimpsed in passing… ‘a country in constant mutation’ as one description puts it. And yet, despite the scale of its subject on the surface, the book remains quietly intimate and reflective, an exploration as much of Postaer himself as of the country he photographs. In his words, ‘I could feel my mother. I could also feel that wonder of what it would have been like if I had grown up there.’

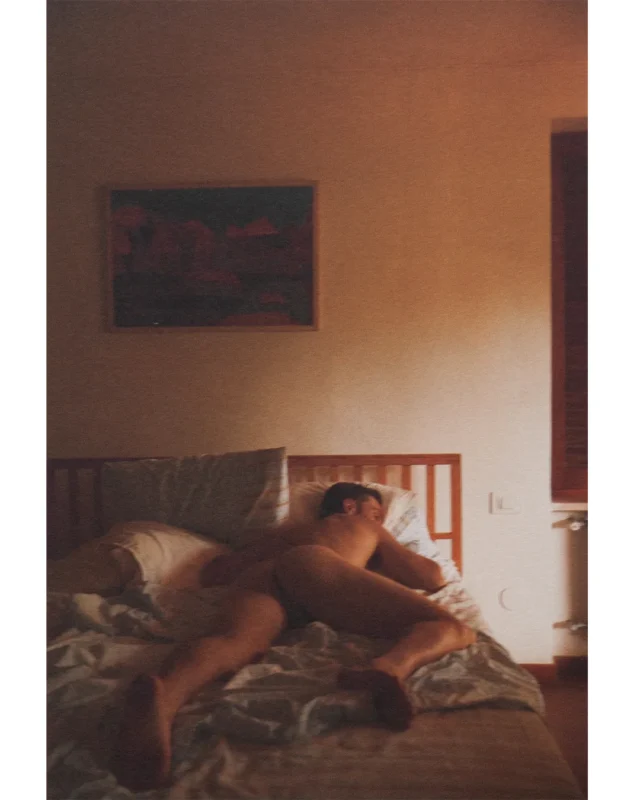

4. Rosie Harriet Ellis, The Boyfriend Casting

Libraryman

From the uncertain beginnings of a project while on her MA at the Royal College of Art, thwarted when her ex-boyfriend withdrew consent, Ellis’ The Boyfriend Casting has, over five years, evolved into a work that consummates the journey of its inception. What initially appeared as a personal and professional impasse has, over time, transformed into an act of reinvention. The book documents this evolution through short, diary-like chapters that feel disarmingly intimate, revealing a presence both within and beyond the frame, while testing how photography can function as tool for grief, yearning and reversed objectification. After the initial photographs of her former partner, Chapter 2 takes the shape of a pose guide. True to its titular promise, it functions as a casting, yet one that is inseparably bound to Ellis herself, her desires, her pursuits of intimacy, and her reckoning with what it means both to observe and to be observed.

5. Mimi Mollica, Moon City

Dewi Lewis

Mimi Mollica’s Moon City stages a spectral dialogue between the eternal and the engineered, juxtaposing the silent, cyclical pull of the moon with the stark, relentless ambition of London’s financial skyline. Shot in a film-noir style and loosely inspired by Luigi Pirandello’s Ciàula Scopre La Luna, the series positions the celestial body as a luminous, enduring counterpoint to high-rise towers, indifferent to human schemes. Through telescopic framing picturing deserted office blocks, Mollica creates a tension between vast skies and the city’s scale of power, choreographing space like a careful negotiator, drawing attention to the rhythms, shadows and silences that punctuate the square mile. As in Pirandello’s novel, the moon offers something else, perhaps a quiet resistance, to anyone daring to look up and escape the deceptive halo of capitalism.

6. Katherine Hubard, The Great Room

Loose Joints

In The Great Room, Hubbard is daughter, caregiver, artist, collaborator. Berger is mother, subject, co-maker. This is the first time Hubbard has photographed another person consistently, and the volume, published by Loose Joints, is shaped by that proximity and closeness, and this goes as far as one-to-one scale contact prints and monoprints made in the darkroom from the impressions of their skin. The house in which the photographs were made becomes a kind of palimpsest of life lived, and the book, in some respects, a record of care and change, of memory inscribed in gestures and the objects that fill it. At its centre lies the mother-daughter relationship, which is tender, uneasy, always shifting between attention and distance and Hubbard neither hides the discomfort nor leans into melodrama.

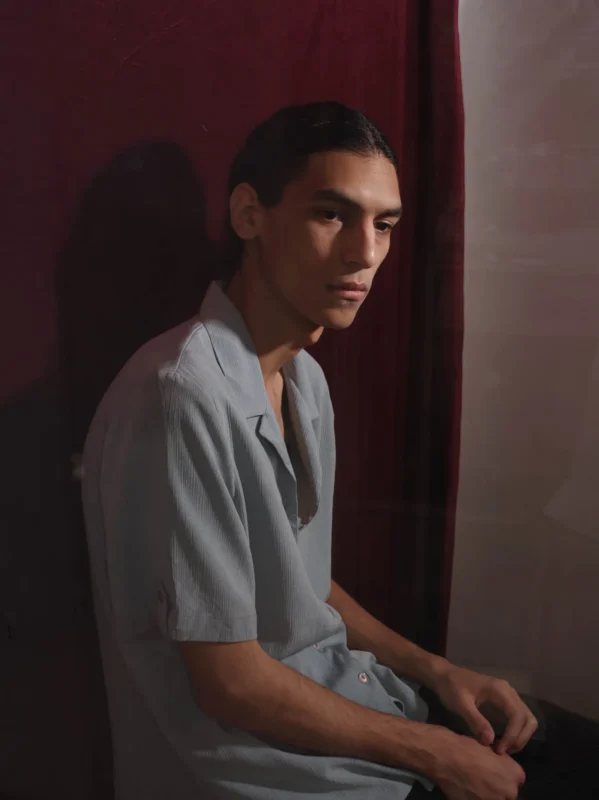

7. Mohamed Hassan, Our Hidden Room

Ediciones Posibles, Fundación Photographic Social Vision, PHREE

Another parental story, and sharing some similarities, is that of Mohamed Hassan, whose Our Hidden Room received the Star Photobook Dummy Award 2024 and was nominated for the Paris Photo–Aperture PhotoBook Awards 2025. At once a response to what some have called ‘the fall of Egypt’s democratic experiment,’ the book draws in part from the photographic archive of his late father, a gifted portraitist diagnosed with bipolar disorder at a young age. Interlacing his father’s surviving images with his own photographs and text, Hassan creates a triptych of inheritance, dialogue and in his own words – a ‘room,’ his and his father’s, as a shared space of return. In a candid conversation with Irene Alison, he reflected that, in photographing, he sometimes feels himself drawing nearer, meeting his father again.

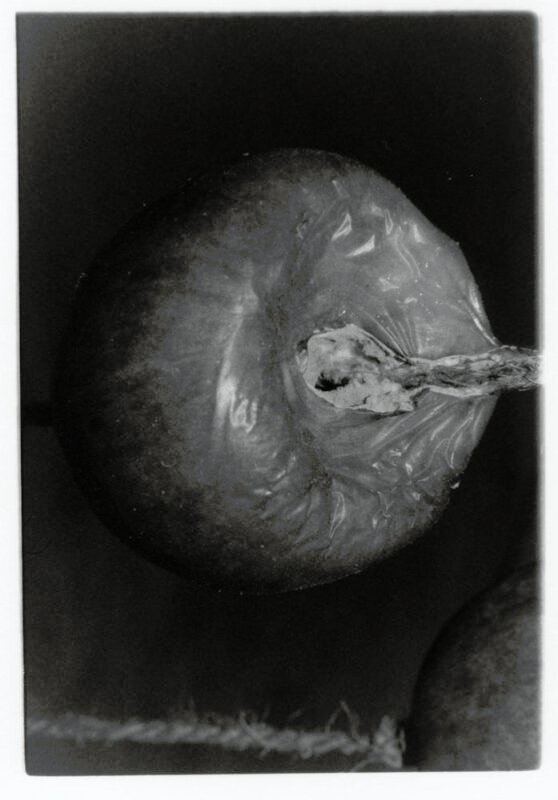

8. Ying Ang, Fruiting Bodies

Perimeter Editions

Jane Simon wrote earlier this year in 1000 Words that Ying Ang’s latest offering (the artist’s third major book and her first with Perimeter Editions) arrives as ‘a provocation to think about abundance beyond the frame of the reproductive body.’ Taking a somewhat more declarative tone than Ang’s previous works, which are notable in their own right, Fruiting Bodies takes us to the unseen networks of mycelium, where ecology and feminist thought intertwine. Neither allegory nor anthropomorphism, it proposes another kind of vitality, subterranean poetics of reciprocity, where decay and regeneration are inseparable. Simon writes, ‘The perspective here is born from the personal, but this is also about a collective experience of how women’s bodies are labelled, classified and devalued over a lifetime.’ The result is strikingly original and surprisingly evocative.

9. Bharat Sikka, Ripples in the Pond

Fw: Books

Fw: Books’ Hans Gremmen continues his thoughtful collaboration with photographer Bharat Sikka, whose sepia-toned studies of Makharda (a peripheral township on Kolkata’s outskirts) and its surrounding landscape form the artist’s latest book, Ripples in the Pond. The softbound volume, with its intentionally unpolished edges, comprises photographs of the area’s many ponds, gently leading the viewer toward the project’s underlying preoccupation with the site’s layered temporal and socio-cultural rhythms. This comes to light in the way that, after each journey to Makharda, Sikka subjects the photographs to an extended practice of scanning and reworking, a slow, deliberate method that mirrors the reflective logic of the ponds themselves. It is a quietly powerful exploration of the ‘semi-rural imaginary’ that leans on the 1980s Indian television series Malgudi Days for inspiration, which portrayed the quiet life of a small town, and, has been described as a ‘personal act of return’.

10. Raymond Thompson Jr, It’s Hard To Stop Rebels That Time Travel

VOID

The ‘rebels’ for Raymond Thompson Jr are the maroons, the runaways, the Black people whose lives moved outside, between, beneath official historical records. Their ‘time travel’ is the movement between the visible and the invisible, the archival and the lived. The project is, in his words, ‘my portal to slip between the past, present and future,’ with focus especially on maroons, enslaved people who escaped but did not go north, instead finding refuge in the wild margin‑lands between plantations, swamps and borderlands, and how their survival practices (what he terms ‘freedom practices’) resonate with Black environmental imagination and presence in the American landscape. Fittingly, the book’s slim, rectangular form recalls a travel guide or field notebook, made to accompany a journey, including archival material such as reward advertisements, quotes, newspaper clippings and truly striking portraits.

+1 Martha Naranjo Sandoval, Small Death

MACK

Martha Naranjo Sandoval’s debut book is a tactile, iterative object – its vivid red cover encasing not only the weight and texture of a generously bound volume, but that of an artist attuned to the material language of memory and making. Spanning some 300 pages, Small Death gathers photographs from Sandoval’s early years in New York, selected from her original contact sheets and reels, a return to beginnings made urgent in a time when ICE disappears people and sanctuary feels perilous. Sandoval’s images quietly respond to this moment through an intimacy reminiscent of a family archive. Photographs of her brother, parents, husband, cat, landscapes, and nude self-portraits stitch together the smaller stories that, in turn, prompt questions around displacement, border-crossing and the violent architectures of exclusion. ♦

—

Tim Clark is Editor in Chief at 1000 Words and Artistic Director for Fotografia Europea in Reggio Emilia, Italy, together with Walter Guadagnini, Luce Lebart and Arianna Catania. He also teaches at The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University.

Thomas King is Editorial Assistant at 1000 Words and currently undertaking an MA in Literary Studies (Critical Theory) at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Images:

1-Cover of Mari Katayama, Synthesis (SPBH Editions, 2025)

2-Mari Katayama, on the way home #005, 2016

3-Phoebe Kiely, She could see herself in the darkness (2025)

4-Daniel Postaer, Shanghai, (Anting), 2016 / 2020

5-Rosie Harriet Ellis, The Boyfriend Casting (2025)

6-Mimi Mollica, Moon City (2025)

7-Katherine Hubbard, The Great Room (2025)

8-Mohamed Hassan, Our Hidden Room (2023-ongoing)

9-Ying Ang, Fruiting Bodies (2025)

10-Bharat Sikka, Ripples in the Pond, (2025)

11-Raymond Thompson Jr, It’s hard to stop rebels that time travel (2025)

12-Martha Naranjo Sandoval, Small Death (2025)

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza

Join us on Patreon today and be part of shaping the future of photographic discourse