Michelle Dizon & Việt Lê

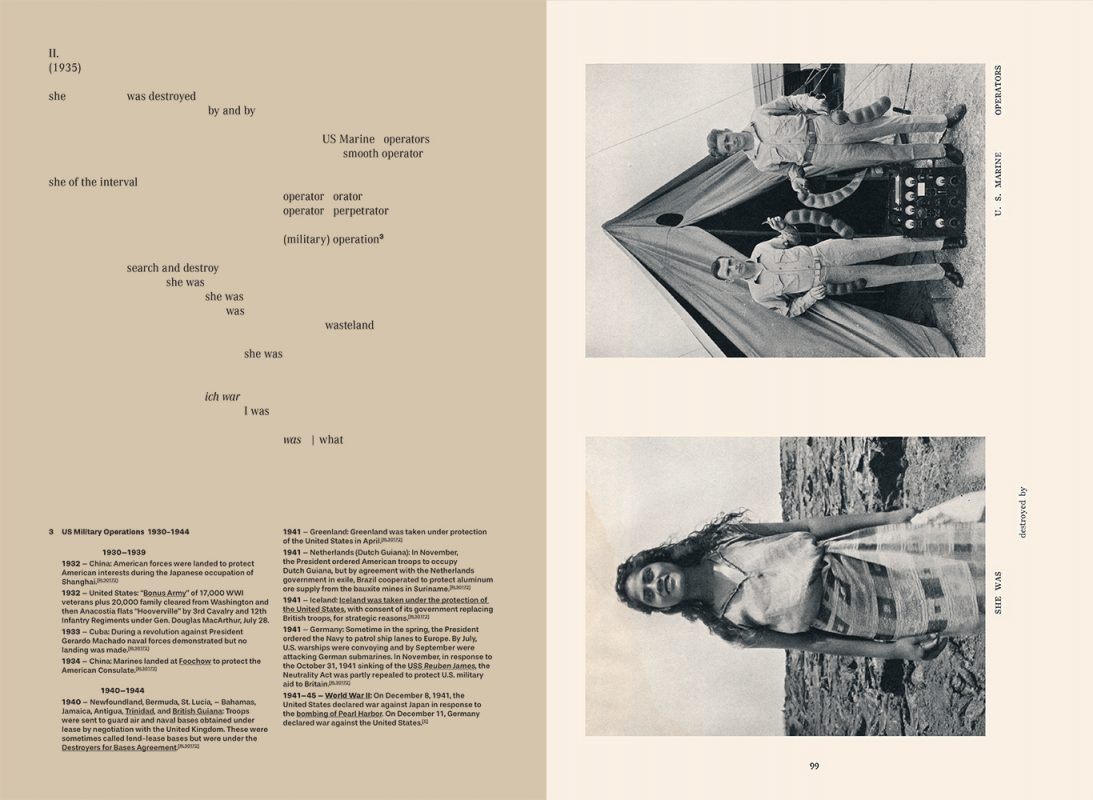

White Gaze

Essay by Daniel C. Blight

At the end of Señorita, a music video by rapper Vince Staples, the camera withdraws backwards from a street scene, through a window and into the ground floor of a house to reveal a white, affluent North American family looking out, smiling at what they have witnessed. This scene is effectively an urban prison. As the song unfolds, its socially diverse characters — working class black, latino, ‘white trash’ men (berating Staples as he walks by), a homeless man and two sex workers — are either celebrated, ridiculed or shot one-by-one by gun surveillance turrets above.

The video’s narrative is a metaphor for contemporary America: bourgeois whiteness reigns supreme at the expense of an underclass, comprised largely of people of colour and those Trump-voting white folks left behind by their middle-class counterparts. The window through which the camera withdraws frames the ‘disturbing’ scene outside for the ‘perfect’ white family to watch from a position of comfort; allowing them to look out both protected by, and in possession of, a ‘white gaze’. This underclass is mere spectacle or entertainment to that gaze. The camera, which tracks the narrative of the video is an extension of this form of ‘white sight’, eventually reclining to safety within the house. As George Yancy writes, ‘It is the social world of white normativity and white meaning making which creates the conditions under which black people are always already marked as different/deviant/dangerous.’ It is this precise sense of difference and danger Staples engages in his video.

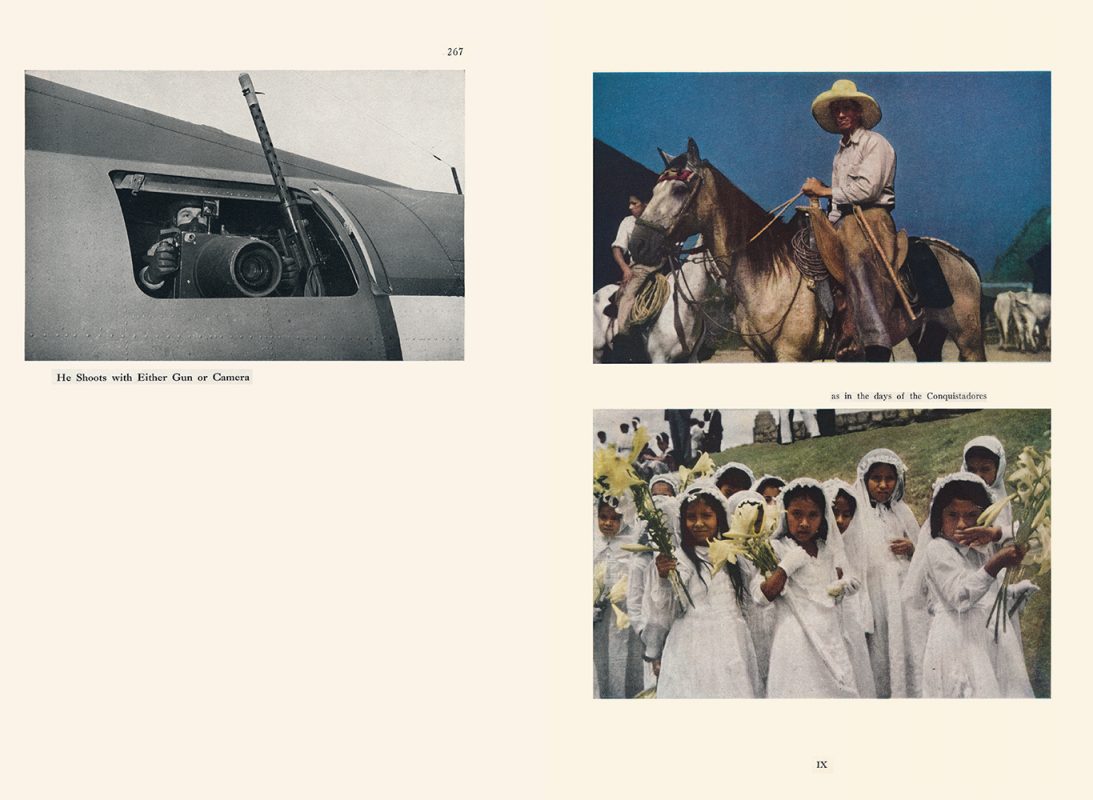

Whiteness, which in this instance takes the form of monstrously bearing witness to from a position of safety, is reflected in a system of class dominance maintained by a violent, colonial prison state more commonly referred to as the USA. Cameras and guns conflate to form a single technological and militaristic entity that protects the hegemony of white power at all costs. Whiteness – which desires to track violence outside itself – is ignorant to the fact that the real source of violence lies within its own house. Whiteness, it might be said, is the root, the provenance and the source of social barbarity from its invention in the early 17th century to its present-day murrain. As Richard Seymour notes in his essay on Salvage, ‘whiteness is a plague.’

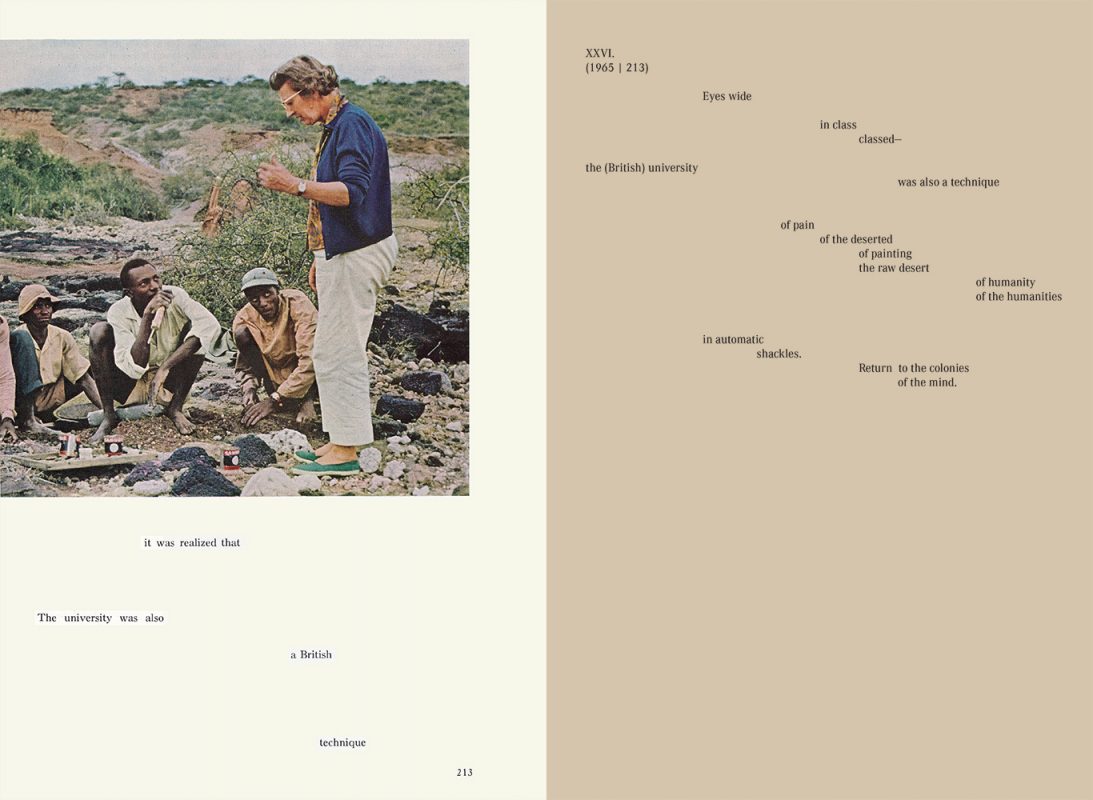

In a poem by Viêt Lê with an accompanying image by Michelle Dizon, whiteness gazes on in the form of a gesticulating white woman standing above three crouching black men. The image suggests she has something to explain; that her knowledge – her performance of a certain kind of education – must be articulated both verbally and physically ‘above’ – thus gazing down upon – the bodies of people of colour. The accompanying poem reads:

Eyes wide

in class

classed—

the British university

was also a technique

of pain

of the deserted

of painting

the raw desert

of humanity

of the humanities

in automatic shackles

Return to the colonies

of the mind.

Here, whiteness takes power as a form of European knowledge, the all-seeing and knowing eye of white sight manifest in the gestures of the white body and the utterances of the white mind. Here the white gaze offers – incognizantly, tediously, repetitively – its intellectual fruits to people of colour on their own land. In a different form of education-as-violence than the colonist Sir Thomas Dale promoted when starting a college along the Powhatan River to ‘educate the natives’ in early 17th century British America, this anonymous white woman professes her ‘unsurpassable’ knowledge to those she deems to be below her cultural imperialism. Criticised directly in Lê and Dizon’s image/poem intersection, the elite British university system is the network of institutions that socialised and educated elites who paved the way for the formation of the earliest inventors of whiteness – a group of governing individuals named the House of Burgesses (a word which is aptly derived from ‘bourgeois’) who, in 1619, forced the first group of twenty African slaves into servitude in the British colony of Jamestown, Virginia.

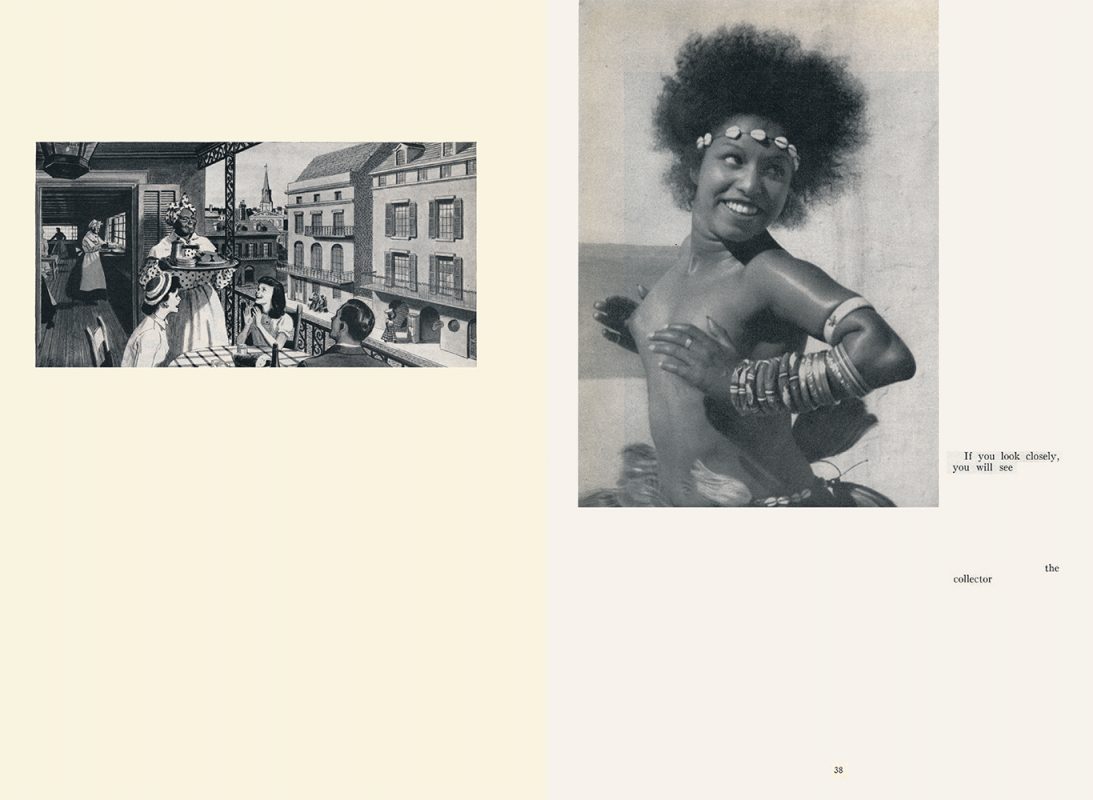

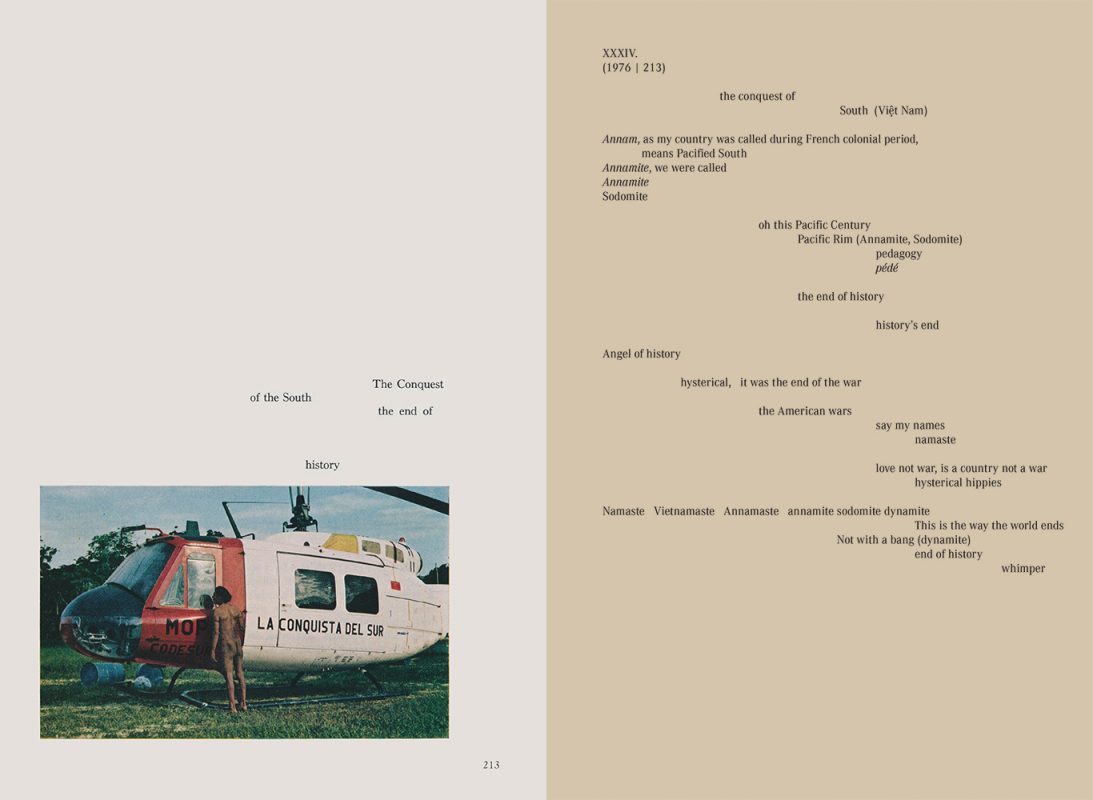

Across multiple images and texts, and spanning various periods of colonial rule by different nations, Lê and Dizon’s White Gaze reveals page-by-page the way in which those socialised white often unconsciously experience – and therefore gaze upon – the world around us. Named after both a philosophical theory and the practice of one of the most violent forms of seeing, this book stands as a potent visual and poetic affront to whiteness.

Central to the idea of the gaze is the notion of desire. ‘In the beginning… desire is always competitive,’ writes Peter Wollen in his essay On Gaze Theory, which traces the genealogy of human desire in the form of looking and wanting from G.W.F. Hegel to Laura Mulvey. The desire of one human portends to the desire of another: I may want what you desire, I may shadow or mimic your desires, and it’s in this kind of relationship that human history might be thought as the ‘history of desired desires’, remarked Alexandre Kojève in a 1947 lecture on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. In this way, you and I are constituted as truly human only when we focus our desire on the desire of an “other”, and, that in this instance, according to Wollen in his reading of Kojève, becoming human is somehow about being self-consciously in competition with an “other” via the gaze as a form of shared desire (because I desire what you desire above all else). I want not exactly what you want, but more precisely I yearn to be within the throes of that which you desire.

In Hegel’s view, during the early 19th century the gaze as a form of power was a struggle between two different kinds of unequal human: the master and the slave. The slave desires to take the position of the master and the master desires the acknowledgement of their power over the slave. At this point we would do well to remember Hegel’s immensely ignorant words on the “Negro” which, as Achille Mbembe reminds us in his On the Postcolony, are ‘an example of animal man in all his savagery and lawlessness.’

This interpretation of the gaze puts emphasis on, as Wollen continues, ‘the possibility of struggle’. In a simple sense this demonstrates that it is entirely possible to desire an object or thing – to struggle to obtain it – because others around us also desire it, not because we actually want it. When we desire things – for example whiteness, to be white, to act white – what form of power dynamics are at play as we do so? When we unwittingly project our white desires onto others, who are we in “competition” with? Might it also be said that we thus desire at the expense of others supposedly unlike ourselves? These are not the only relevant questions in the case of Lê and Dizon’s White Gaze, which begins to ask what the relationship between a certain form of white desire and photographic images might be?

Much like the way in which Vince Staples’ video seeks to metaphorise White America as a form of racialised power – the final scene literally framing the world of people of colour as an urban prison apart from the white familial space of comfort – Lê and Dizon’s project demonstrates that the history of photographic images and the camera itself equally reflect forms of deeply violent white sight. In my view, the importance of White Gaze is that it uses photography and poetry to ask white people to feel less comfortable in our whiteness (and for an increasing number of us, our new-found ‘wokeness’) and instead find ways to meaningfully resist our own white subjectivity. As George Yancy quite rightly suggested at a symposium in response to the question what should white people do? – and we white people might think of this book as a catalyst for the same action – “I want them to confront their own whiteness. That’s the kind of honesty I’m looking at; the kind of humility I’m looking at. That fearlessness to be torn apart… White people should go home tonight, get naked, look in the mirror and ask themselves, what’s so special about me?” ♦

All images courtesy of the artists and Sming Sming Books. © Michelle Dizon & Việt Lê

—

Daniel C. Blight is a writer based in London. He is Lecturer in Historical & Critical Studies in Photography, School of Media, University of Brighton; Visiting Tutor, Critical & Historical Studies, School of Arts & Humanities, Royal College of Art and Online Editor, Viewpoints at The Photographers’ Gallery, London.