Alba Zari

The Y

Essay by Ilaria Speri

The most disconcerting photographic moment in my life dates back to five years ago. My 87-year old grandmother was experiencing – we did not yet know – an early stage of senile dementia. One day I stepped in her apartment and I noticed that the armchair in her living room was surprisingly occupied, albeit with a black and white portrait of my grandfather, the one, which had been sitting on the television since his passing, was nicely accommodated onto it. A blanket covered him up to his nose, so that he could breathe, and a pillow softly held his head. She had literally put him to bed. From then on, any printed or moving image would become so ‘real’ to her, that in a few months she could no longer see the difference between a person and its reproduction – images had taken over.

Photographs are known to be an ideal means for building and preserving memories. Their power over our perception of the world is immeasurable. They provide strangers with an identity, and they help us remember those who have left. They comfort us in the blank spaces of someone’s absence – when we remember, or when we wait. They are proof of our existence. Among many other reasons, this is what makes humanity’s bond with photographs umbilical. We can’t do without them. And if this wasn’t enough, they are always available.

The Internet and new digital technologies have shifted immensely the ways in which we represent ourselves, multiplied by our existence on the web. Allowing us – by ‘simple’ means of images and coding – to bring back the dead with strikingly reliable results. A significant example, among others, is Cécile B. Evans’s video piece Hyperlinks Or It Didn’t Happen (2014), a poetic monologue on consciousness and personal data narrated by a digital copy of deceased actor Philip Seymour Hoffman, populated by spam bots, holograms, and rendered ghosts. Proof that the distance between the real and the virtual is wearing thinner and thinner.

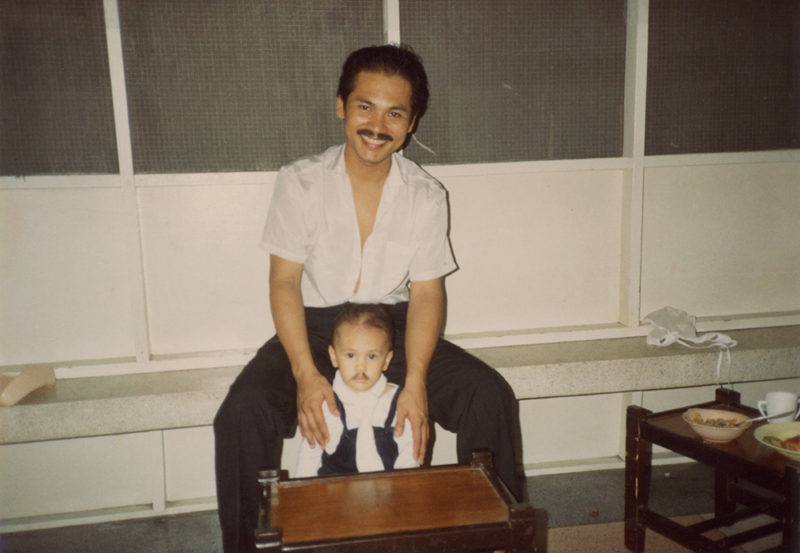

Picture this. What if you were to track down the image of a person you know exists, but never met? This is what Alba Zari, born in Bangok in 1987, started thinking after January 4th, 2014, when she found out that the man appointed in her memories as her father was not, as a matter of fact, her biological parent. An unexpected revelation made by her brother, with whom she was sure to share Thai biological origins. A DNA test confirmed the fact with an unquestionable 0% match. Zari was confronted with the sudden disruption of her identity and sense of belonging. She decided to assume the role of a detective, and started the private investigation that she conveyed in her project The Y, a title referring to the male chromosome of human DNA. What emerges is a medical-cum-conceptual visual report, which brings to the surface some of the most interesting features that make photography such a uniquely fascinating language.

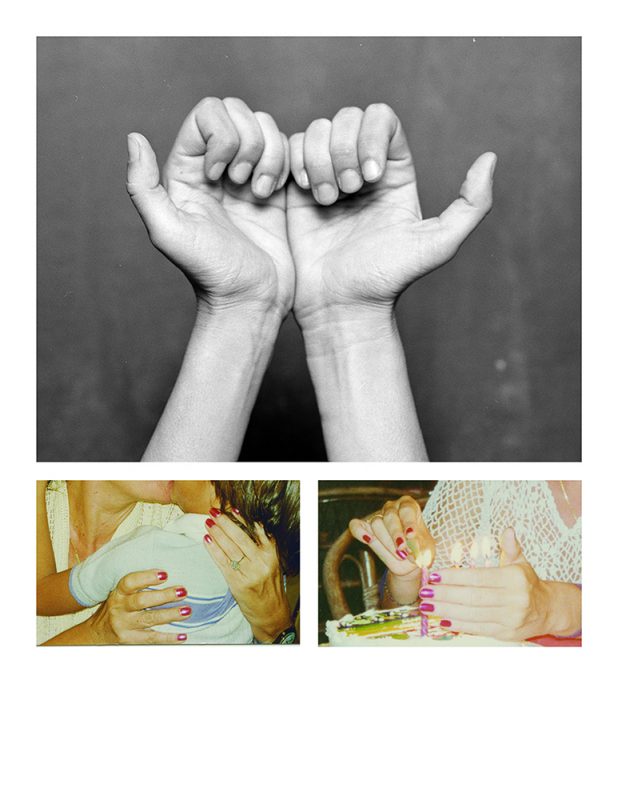

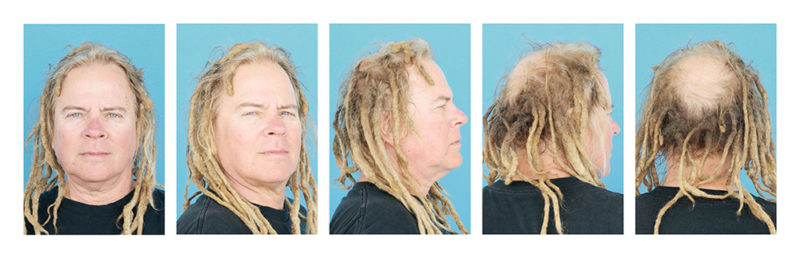

Despite the autobiographical premise, the project is marked by an infrequent – as much as remarkable – capability of the artist not to take control over her own story. She leaves room for the puzzle to come together through attempts, failures and discoveries, rather than imposing an unnecessary – as much as painful, as the artist specified in a previous conversation – dressing of emotional involvement and storytelling. As a result, the series pays homage to a long history of medical and forensic photography, and of its transformation into artistic processes – from Duchenne de Boulogne and Adrien Tournachon’s famous electrophysiology experiments, up to Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s pioneering photo-book Evidence (1977). Travelling the world both physically and virtually, from Thailand to the United States to YouTube, Alba Zari’s work merges scientific reports, archival images, film negatives, personal relics, mugshot portraiture and 3D facial construction.

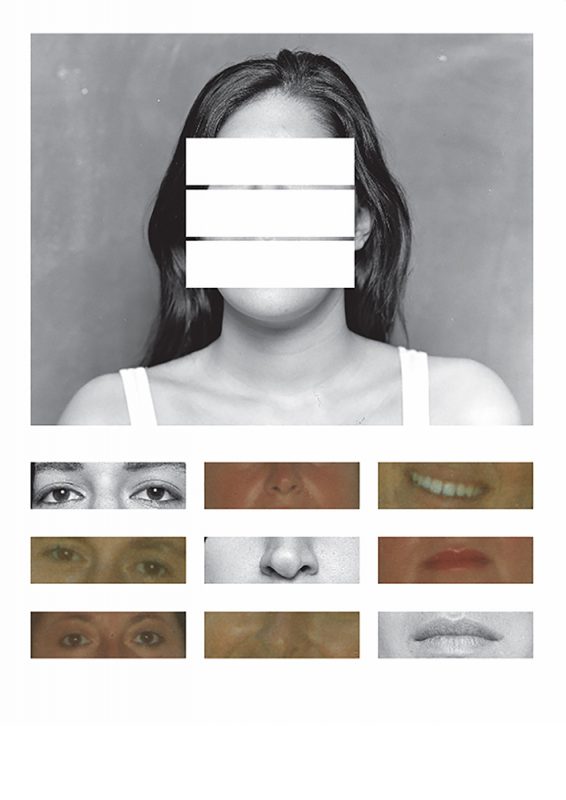

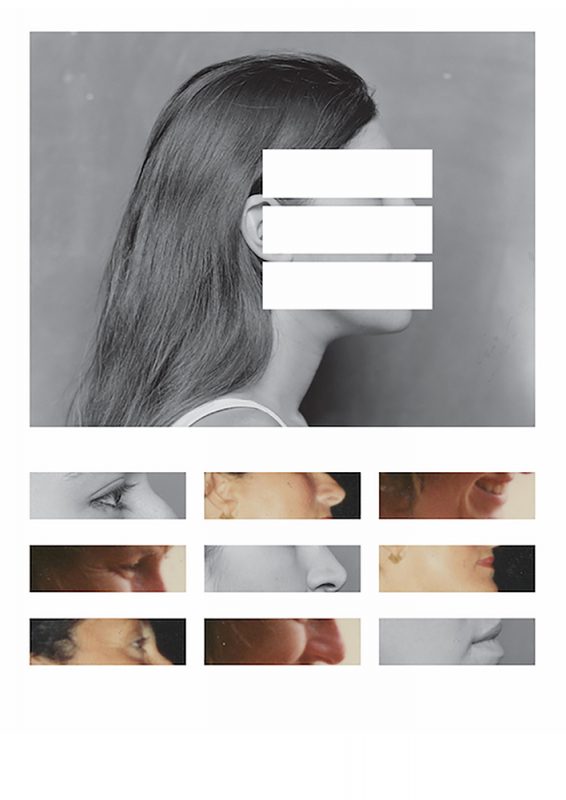

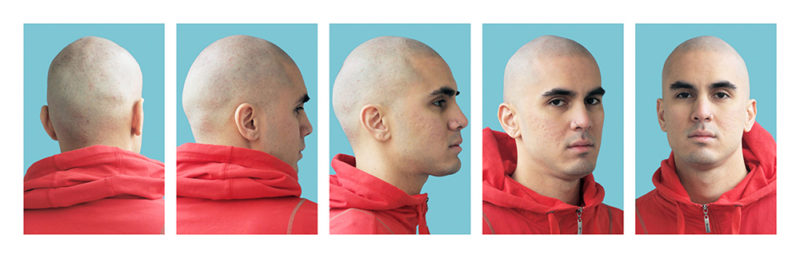

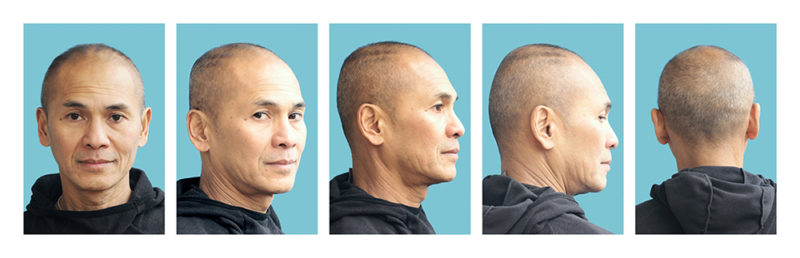

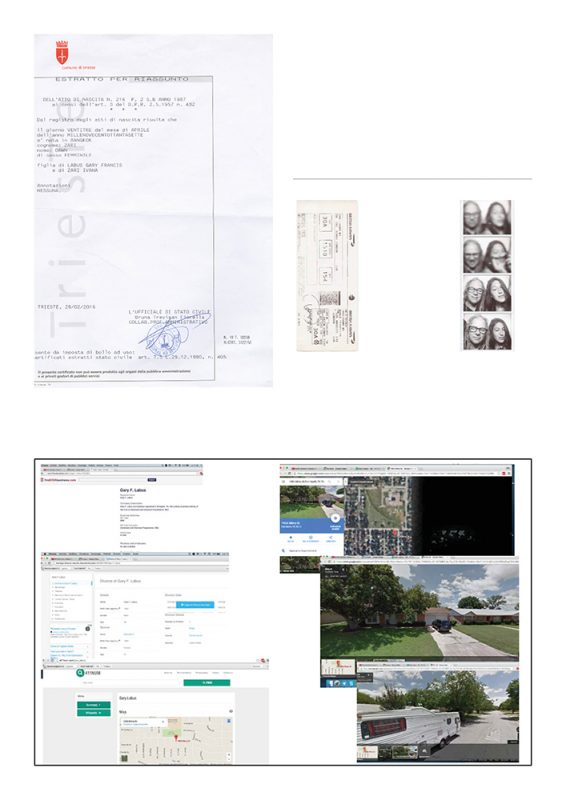

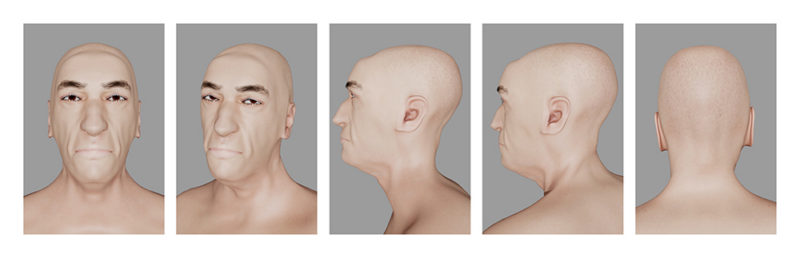

Once Zari obtained her birth certificate, she reached out to the man who had signed it, who, following colossal searches on the Internet, turned out to be homeless person living in Santa Barbara, California. In the series, the man appears next to her putative father and brother in sequences of 360° portraits – the kind used to determine facial traits in digital imaging. At the end of the journey, all she knew – and currently knows – is that her father’s name was Massad, and that he used to work for the Emirates Airlines. She analysed her family album, painting over a no-longer reliable fatherly figure, before turning to the process of exclusion deployed in physiognomic studies, a test based on her mother and grandmother’s traits as well on her own. Highlighted in a large-format self-mugshot, it quite clearly revealed that her nose, mouth and eyes bear a striking resemblance to those belonging to Massad. However, she hadn’t yet been able to find anything close to an image of the man himself.

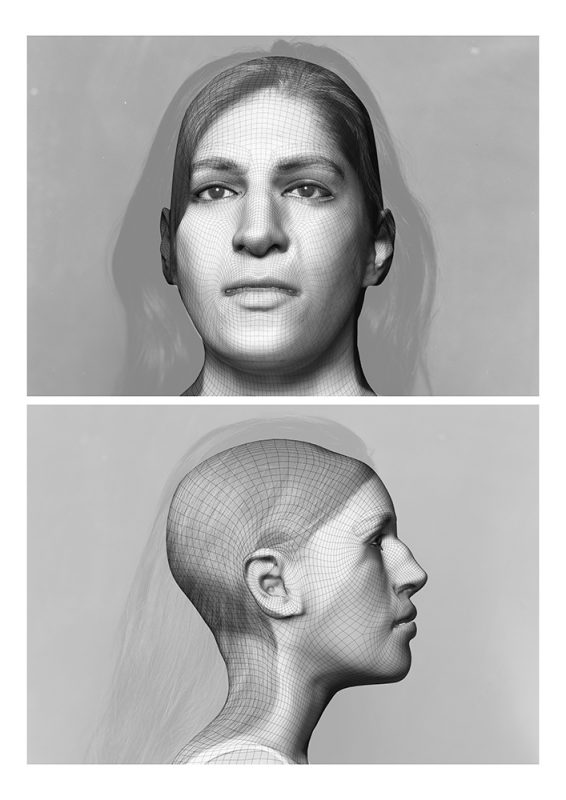

Zari’s ultimate attempt sees the use of Make A Human, a software usually employed to design avatars in digital animation. Here, she created a digital identikit by applying her facial traits – those belonging to her father’s side – to a neutral digital model. In visual terms, what is most interesting about the renderings that today’s software can provide – as pointed out by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin in their unsettling series Spirit is a Bone (2015) – is that despite their plausibility they are designed to look straightforward. From every angle we look at them, their gaze bypasses us, pointing towards another dimension – one we have no access to. The complete absence of interaction, of human interconnections, marks the occurrence of a major transition in the notion of portrait itself, one which will no doubt require further explorations in the future.

Eventually, the project reaches an end with the nearest visualisation of the man the artist could achieve – an avatar of his presumed face. Only the web may still represent a lifeline for soon the 3D portrait will be released online and spread worldwide in a global open call to help with the ongoing process of identification. The results are unpredictable. In the artist’s words, the rest is about life. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Alba Zari

The Y is curated by Francesca Seravalle as part of a fellowship at Fabrica – The Communication Research Centre of the Benetton Group.

—

Ilaria Speri carries out research, curation and production for exhibitions and publications. Since 2013 she has been part of Fantom, a curatorial group dedicated to photography, visual and sound arts. A correspondent at Il Giornale dell’Arte, she writes for magazines and artists books, and has collaborated with publishers such as MACK, Humboldt Books, Skinnerboox and Skira. She taught History of Photography at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna from 2014-17 before taking up the role of Curatorial Coordinator at Fotopub festival (Novo Mesto, Slovenia), for which she curated the first solo show of the collective Live Wild in 2016.