Anselm Kiefer

Photography in the Beginning

Exhibition review by Mark Durden

Mark Durden visits Anselm Kiefer’s new show at LAM – Lille Métropole Musée d’art modern d’art contemporain et d’art brut, centred on the significance of photography for the German artist’s work. It reminds us that in his hands photographs are never simply a document: predominantly black and white, they are a skin to be marked and scored upon, collaged, contaminated, painted over, covered in clay, scattered with sunflower seeds, scratched, torn; as much a surface as an image.

Mark Durden | Exhibition review | 16 Feb 2024

Anselm Kiefer: Photography in the Beginning at LAM – (Lille Métropole Musée d’art modern d’art contemporain et d’art brut) is the first major show centred on the significance of photography for the German artist’s work. In this intriguing and multi-faceted exhibition, also involving sculptures and paintings, we get a clear sense of his treatment and relation to photography – it is a refreshing use of the medium and somewhat distinct from the dominant narratives of the history of photography (Kiefer refers to photography as his “sainted assistant” and has only partially and rarely presented this important component of his practice before).

“How can anyone be an artist in the tradition of German art and culture, after Auschwitz?” French art historian Daniel Arasse raised this question in his 2014 book-length study of Kiefer. And while many of the works on show explore myths, traditions and beliefs that go beyond the Holocaust – it is still a question that haunts this exhibition. Swathes of German culture had been tainted by their appropriation during The National Socialist regime and Kiefer’s emergence as an artist saw him confront this tradition, drawing upon quasi-mystical and ritualistic realms to address this contamination, effecting a mad or crazy romanticism, in which the artist’s antics send up Nazism. In the face of cultural consensus in The Federal Republic of Germany or “West Germany” condemning cultural allusions connected with the barbarity of the past, fascism’s image-world, Kiefer’s emergence as an artist, having been born in 1945, was very much as a taboo breaker and transgressor: someone who would not remain quiet.

What comes across from this show is an odd mixture and clash of values and beliefs. When Kiefer presents himself in photographs, mostly dating from the late 1960s but often reworked in the 2000s, he is an actor, a performer. What these actions signal and signify is fraught with conflict. Mystic? Romantic? Trickster? In fact the show begins with a photograph from the late 1960s, overpainted with gouache, showing the artist wearing a dress and standing on a chair. He is holding a branch with leaves. He seems to be evoking nature’s power of growth, regeneration and healing. He adopts or plays the role of healer after the darkness. This first room is entitled Nigredo, Latin for blackness, a reference to the first step in alchemy, the state of black matter from which the philosopher’s stone is made. But blackness and darkness also take on meaning in terms of Nazism and a history that his art refuses to remain silent on.

This exhibition has a lot of captioning texts, which help orient us in navigating our way through his complex iconography. Or rather an iconography made complex through citations and allusions to literature and culture, which as a viewer can be overwhelming. But materially the art is often blunt and direct, unrefined; a recurring tension or collision in the works. On one hand a raw visceral immediacy and directness of how materials are used and on the other the weight and richness of high cultural allusions.

The photograph is very much a medium for Kiefer, a receptive surface that in its use by the artist is never simply a document. Predominantly black and white, it is a skin to be marked and scored upon, collaged, painted over, covered in clay, scattered with sunflower seeds, scratched, torn; as much a surface as a picture.

The condition of many of his photographs might be described in terms of contamination – stained, mounted on lead, which is sometimes visibly corroding and changing. Lead for Kiefer is an important medium for its alchemical associations. It might also be seen to have a correspondence with photography itself – grey, melancholic and mutable.

Before the first room, a large photo mural shows the artist as photographer, his shadow cast against the emptiness of the Sahara desert, a void marked also by receding tire tracks. The picture might be seen to feed a myth of the lone male artist creator, a romantic portrait in which the world is a blank surface awaiting him to make his mark. But at the same time it is only his shadow, a fleeting and momentary trace of the artist.

In some of his most striking and well-known photographs, Occupations, dating from 1969, Kiefer enacts a comedic reprisal of the legacy of Nazism, in which, sometimes adorned in his father’s military uniform, he adopts the Hitler salute in places in countries formerly invaded by Germany. The romantic implication when this gesture takes place in front of the sea is undermined by a comic shortfall, especially evident in the pages of some of his early artist’s books – on show in vitrines and on a video screen – showing him standing and saluting in a full bathtub in his studio and appearing to “walk on water”. The Nazi salute was, and still is, an illegal act in Germany and one that acknowledges and responds to the silence of the time: “authority competition, superiority… these are facets of me like everyone else. I wanted to find out what I would have done back then.”

The first room is dominated by a large photograph of a young Kiefer lying down and adorned in a crochet dress, but also giving the Nazi salute. Entitled Pour Jean Genet, it draws attention to a writer important to the artist: “I still feel the same fascination for the dichotomy he sustains between light and darkness, flesh and crystal, for his search for the duality between saintliness and abjection”. The photograph was pasted onto lead before undergoing the chemical process of electrolysis. The effect is visually striking, the colours and staining of the photograph and the transformation of lead, all materially reiterate the indeterminacy of the figure of the artist, counteracting militarism by cross dressing.

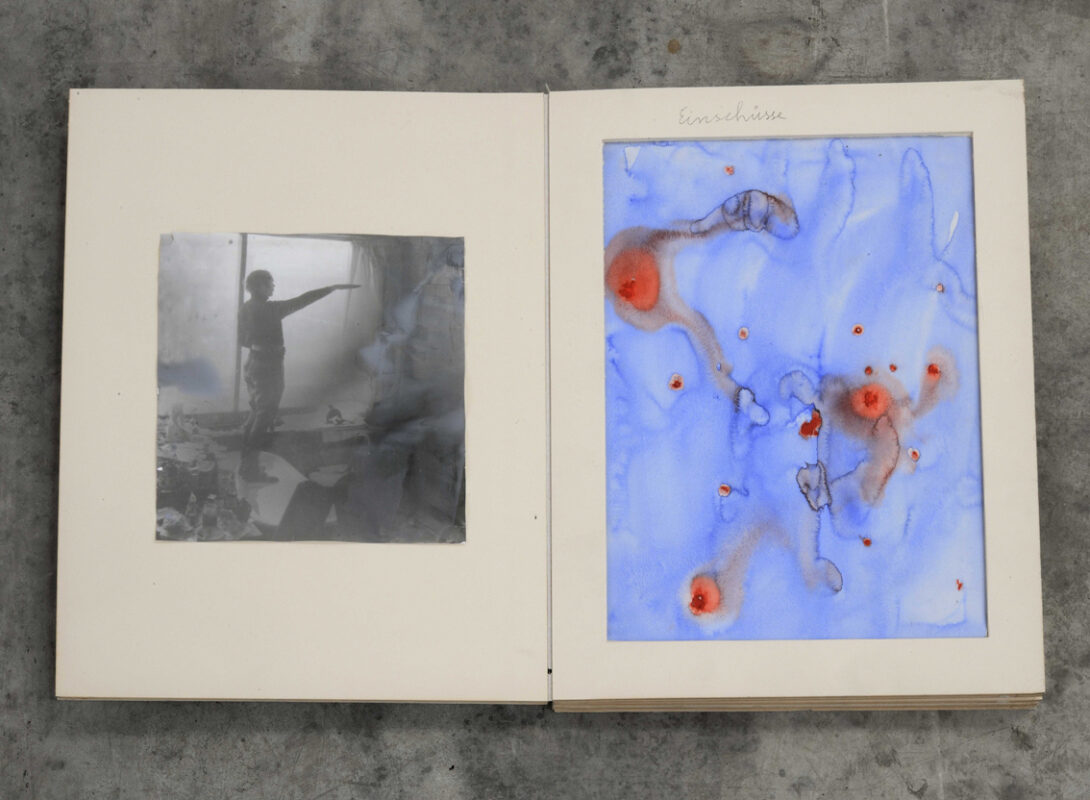

Since the end of the 1960s, Kiefer has constantly created unique books from photographs and various materials. Two rooms are given over to the books, in steel vitrines and atop lead tables. Three large-scale books are made available to physically view, one in colour offering a powerful succession of views of tunnelled excavations in his expansive artist’s famed estate in Bajac, France – a fascination with something primary and basic, a stripping back of creation to a raw encounter with matter.

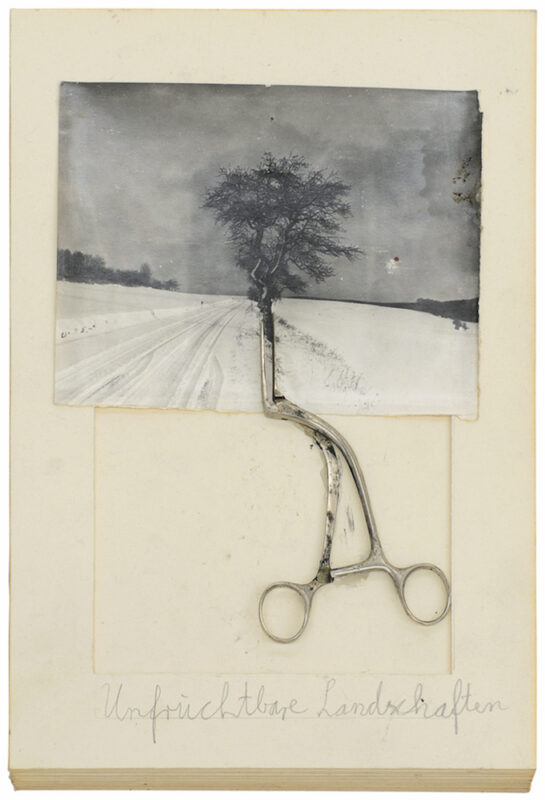

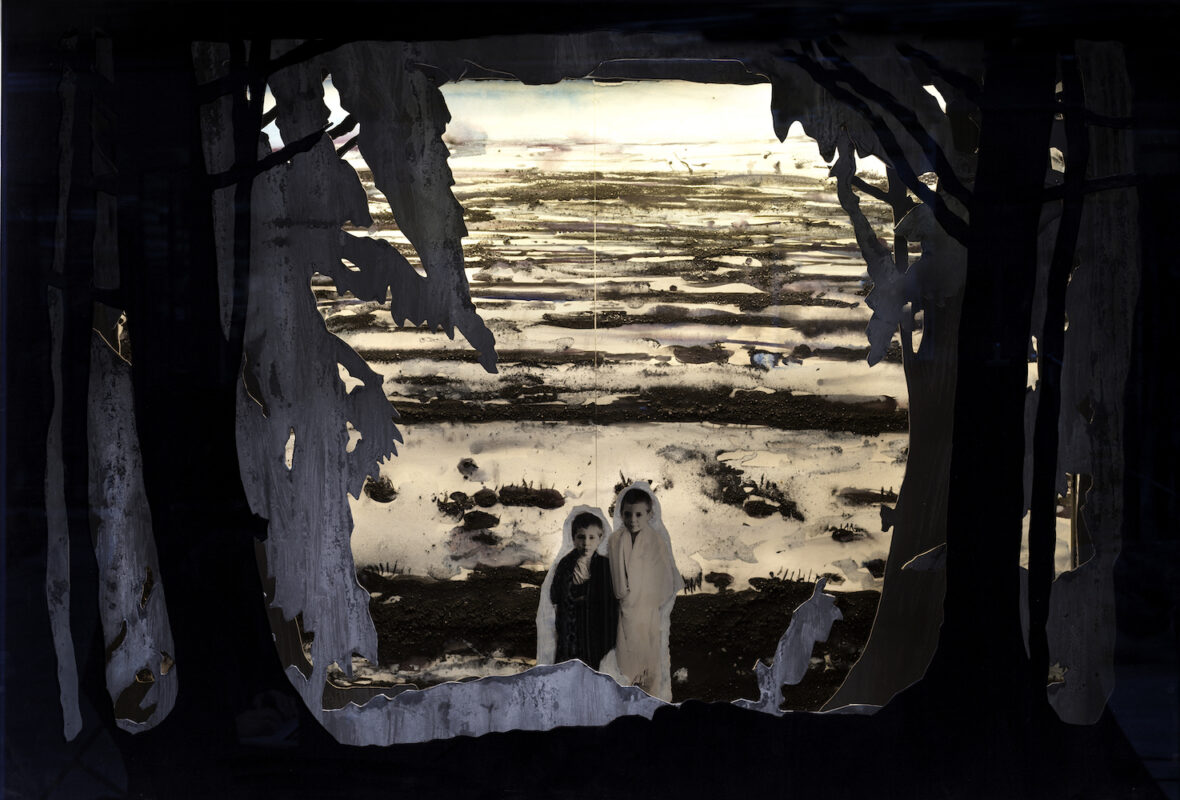

For Kiefer the German landscape is marred by the violent history of the past – a series of photographs of disused railway tracks become tragic in their allusion to the trains to the death camps. In some of the most direct uses of photographs, landscape photographs are covered with barbed wire or surgical instruments, an emphatic insistence on his de-innocenting of the romantic landscape tradition. Photographs of sunflowers could evoke the paintings of Van Gogh but are often pictured black against the light and the photographic surfaces tinted and splotched. Elsewhere in a rarely shown series, Kiefer presents sixteen dioramas, snow-covered forest scenes combined with cut out photographs, many drawn from family photographs. But much as some offer lighter scenes, a wedding couple, children, the darkness of the past lingers and breaks the spell and magic of these little scenes – in one, a figure is hanging from a tree.

Conceived in the wake of the trauma of German history, it is not surprising that we counter ruin after ruin in his use of photographs. The photograph itself is in a state of ruin, or indeterminacy, often stained and corroded. Contamination becomes a good word to describe the state of many of his photographs in light of the abiding themes and concerns of his work. For example, in one striking wall-sized work, a large torn photograph on lead that is corroded, sets up an interplay between the picture’s ruinous state and a photographic composite bringing together the image of a Greek temple and a brickworks in India, a place of primary production and construction set against the relic of Classical western culture, an evocation of two very distinct architectures and worlds.

In a different room, we encounter a series of works drawn from Jewish mythology and a more troubling association in the evocation of the female figure of Lilith, Adam’s first wife, a demonic force and uncontrollable seductress, often symbolised by her long black hair in the artist’s works. Her name and black hair floats among a haze of ash covering a large-scale painted aerial view of a sprawling city, drawn from photographs of São Paolo.

Kiefer’s obsessions and themes recur through his photographic imagery – the sunflowers, the sea, the forest, snow covered fields, the railway tracks, as well as the spectacle of ruins and the transformative site of his studios. If there is a shift in his work from the weight of German history, it is an opening out to more cosmic and abstract themes, the focus on creativity in relation to the unfathomable beyond. Photographs of the underground spaces that he had dug into the hill of his French estate represent an unresolvable quest and searching, very much like the experience of his art itself. This is its richness, a sense that we cannot readily frame or contain it. We hazard a guess, blunder around for meanings. And signs and meanings are in abundance in this work, but we are never quite sure how to make sense of them. Things are not fixed but mutable like the state of many of his photographs.

By the end of the show, a large-scaled photograph mounted on lead, shows the back of the artist, standing at the edge of the Rhine looking towards the other shore. It is a reprisal of Caspar David Friedrich’s rückenfigur (“figure from the back”), but the message is different. Despite the picture’s size, the artist’s pose is not about self-aggrandisement, mastery or heroic power. Rather, according to a quote from the artist, it is a stance and position caught up in the idea of borders and being between: “When I speak of borders, I speak of our very essence. […] We are the membrane between the macrocosm and the microcosm, between the inside – what we are – and the outside, what we also are. […] Art itself is a frontier, defined by the notion of limit: it is always on the razor’s edge, on the edge between mimicry and abstraction.”

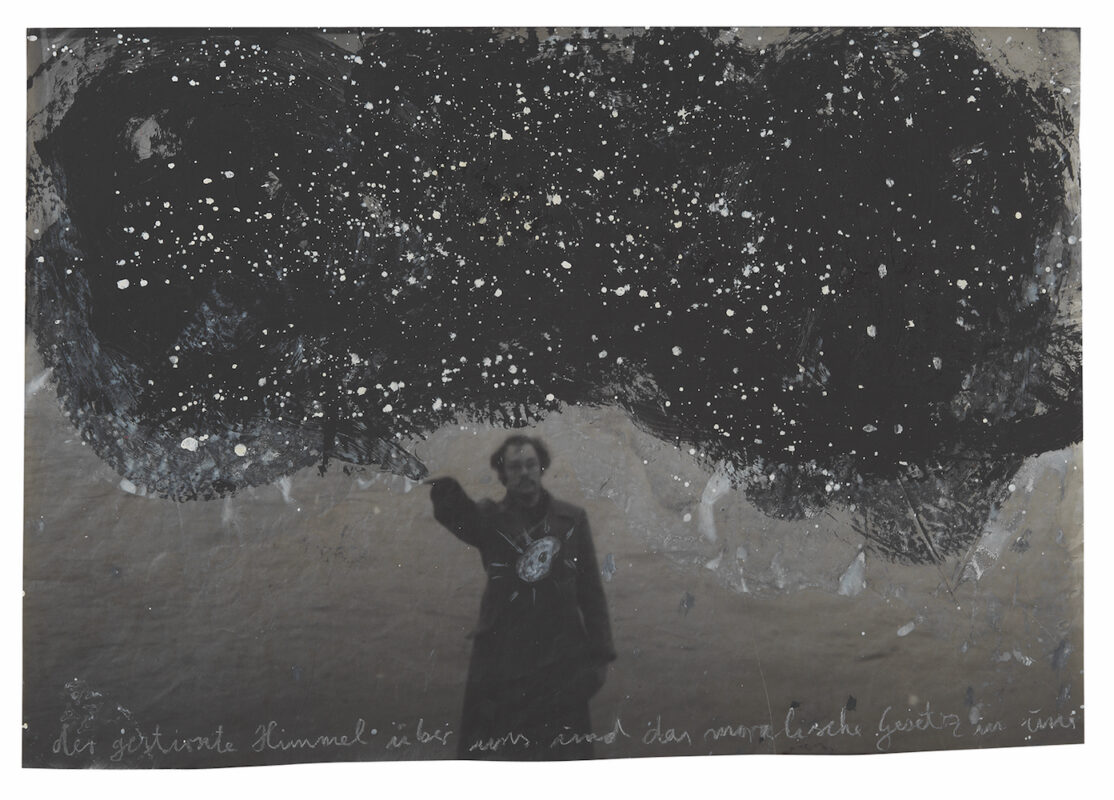

Keifer’s art is one that is full of tensions and oppositions. In many ways for all the destruction and contaminations in his use of photography, his ceaseless production and creativity is marked by an enduring faith in art and culture. Another work from his Occupations series has been painted over, fifty years later. A palette with little radiant lines around it has been painted upon the image of his chest and dots of paint over black have been added to represent the stars above him. A quote from Kant accents the dichotomy central to the picture – “The starry sky above us and the moral law within us”. In revisiting and reworking this early photograph he spells out a tension and opposition that rebounds throughout the works in the show. The cosmos, something beyond and unfathomable, is set in relation to our own morality – our potential for goodness and creativity which is symbolised by the artist’s palette, but also our potential for evil, the abject sign of fascism in that Sieg Heil gesture. ♦

All images courtesy the artist and LAM – (Lille Métropole Musée d’art modern d’art contemporain et d’art brut) © Anselm Kiefer

Anselm Kiefer: Photography in the Beginning runs at LAM until 3 March 2024.

—

Mark Durden is an academic, writer and artist. He is Professor of Photography and the Director of the European Centre for Documentary Research at the University of South Wales. He works collaboratively as part of the artist group Common Culture and, since 2017, with João Leal, has been photographing modernist architecture in Europe.

Images:

1-Anselm Kiefer, Für Martin Heidegger Todtnauberg (For Martin Heidegger Todtnauberg), 2010-2014. Black and white photographs, chalk, charcoal and silver leaf on cardboard; 20 pages (9 double-pages + cover and 4th cover); 103 x 66 x 4 cm © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat

2-Anselm Kiefer, Unfruchtbare Landschaften (Barren Landscapes), 1969. Black and white photography, surgical instruments and graphite on cardboard. Hardcover book, 14 pages; 36 x 25 x 4.5 cm. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat

3-Anselm Kiefer, Der gestirnte Himmel über uns und das moralische Gesetz in uns (The Starry Sky Above Us and the Moral Law Within Us), 1969-2009. Gouache on photographic paper; 58.90 x 83.90 cm. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Atelier Anselm Kiefer

4-Anselm Kiefer, Family Pictures, 2013-2017. Set of 16 display cases, Metal, glass, lead; 385 x 145 x 145 cm © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat

5-Anselm Kiefer, Am Anfang, [In the Beginning], 2008. Oil paint, emulsion, lead and photography on canvas; 380 x 560 cm. Grothe Collection at the Kunsthalle Mannheim, Germany. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat

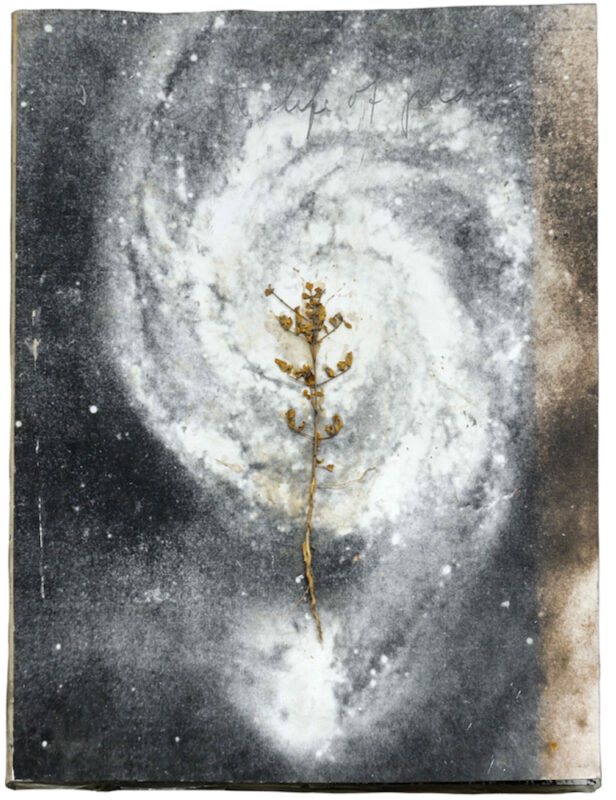

6-Anselm Kiefer, The Secret Life of Plants, 1998. Photographic reproductions, plants, graphite; 64.50 x 50 cm. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat

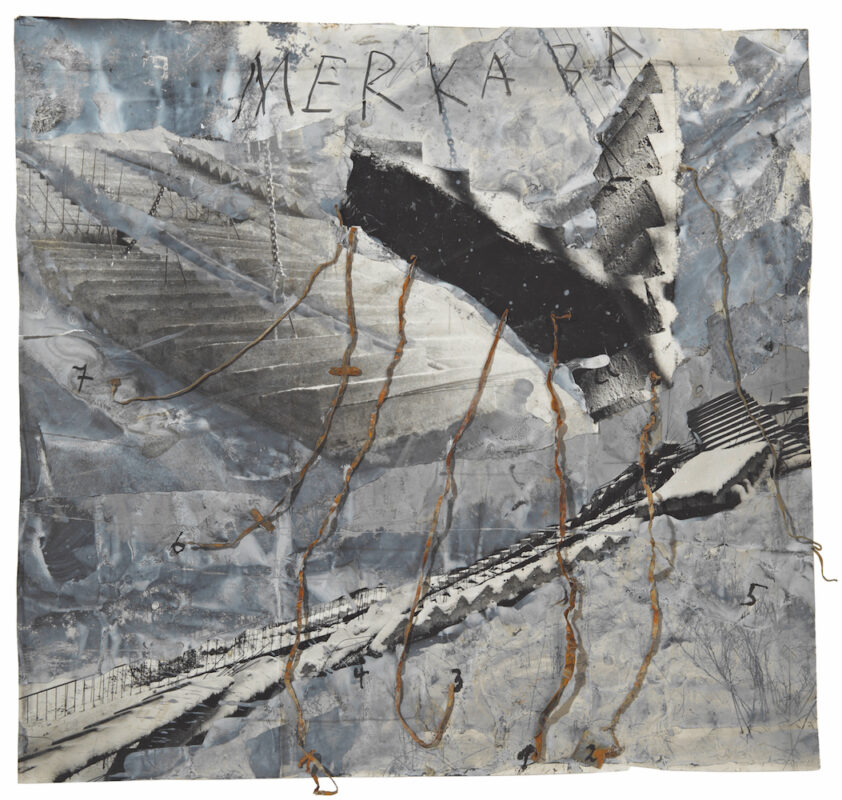

7-Anselm Kiefer, Merkaba, 2005. Gouache and lead on black and white photograph; 43.6″ x 45.5″. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Atelier Anselm Kiefer

8-Anselm Kiefer, Sonnenblumen (Sunflowers), 1994-2012. Tinted silver photographic print under glass in a steel frame; 103.5 x 160.5 cm. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat

9-Anselm Kiefer, Der Rhein [The Rhine], 1969-2012, Electrolysis on photographic print mounted on lead, 380 × 1,100 cm. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Georges Poncet

10-Anselm Kiefer, Calmly Unendingly Moves (für J.J.), 2023. Glass, steel, lead photography and mixed media; 385 x 145 x 145 cm. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Georges Poncet

11-Anselm Kiefer, Bergkristall, detail of the Family Pictures installation, 2013-2017. Set of 16 display cases. Metal, glass, lead, wood, plywood, acrylic, emulsion, photography, watercolour on paper and mist technique; 351.5 x 1400 x 100 cm. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Georges Poncet

12- Anselm Kiefer, Am Anfang, [In the Beginning], 2008. Oil paint, emulsion, lead and photography on canvas; 380 x 560 cm. Grothe Collection at the Kunsthalle Mannheim, Germany. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat

13-Anselm Kiefer, Ohne Titel, (Untitled), 1969-2009. Gouache on photograph; 110.5 x 86 cm. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Georges Poncet

14-Anselm Kiefer, Heroische Sinnbilder, [Heroic symbols], 1969-2010, Black and white photographs, gouache, watercolour on paper and graphite on bound cardboard, 10 pages, 60 × 45 × 4 cm. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Atelier Anselm Kiefer