Craig Atkinson

Café Royal Books

Exhibition review by David Moore

Currently exhibited at The Photographers’ Gallery in London, Craig Atkinson’s Café Royal Books presents an eclectic collection of social relics where regional pasts intermingle, and previously unseen or half-remembered social histories are vividly recalled. With a sense of relative authenticity, the exhibition invites viewers to delve through a collection of three hundred books that capture past lives through the lens of another. David Moore reflects on the display and the project’s position among the ongoing reassessment of documentary photography.

David Moore | Exhibition review | 11 Apr 2024

As documentary photography finds new form amidst recurring questions of its legitimacy and purpose, Craig Atkinson’s monumental publishing project, Café Royal Books, presents a crowd-pleasing repository of the photographic distant, that in its entirety could be understood as a document itself of a particular photographic age.

A relatively small display of CRB’s output is currently installed at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, giving a glimpse of its residual value. The project presents an eclectic collection portraying mainly British, but also international, work of previously unseen or half-remembered social histories. Without acknowledging it, CRB shows “documentary photography”. Atkinson says: ‘Documentary is just a term like any other, and really I use it to help define what I don’t publish, rather than exactly what I do.’ The project presents works, loosely spanning 40 years. Browsing the catalogue online, I found content from the late 1940s (Dorothy Bohm’s pictures of Paris) to the 2010s (Thabo Jaiyesimi’s Nation of Islam UK 1989–2018, published last year). In-between is a diverse collection of the eccentric, mundane, the archetypal and unexpected; everything really.

CRB is driven by “functional” and environmentally light economy to allow all of this. Atkinson describes his project as being ‘somewhere between craft and punk,’ which is an apt description of his stripped down, DIY, home-made ethos. Production is cheap, retail price kept to affordable rates, ‘based around the price of a London pint.’ Pre-production, the photographer is asked to provide scans, a sequence and title, then is offered a design that is tweaked, over email. The book’s release is scheduled, and that’s it. Occasionally, special editions are offered, or second editions published.

CRB shares characteristics with the larger publishing houses. The model excludes any monetary payment to the photographer, an arrangement that has become routine for the publishing of books in recent years (only a handful of very well-known artists make any profit from direct book sales). With CRB, the photographers are offered a portion of books for themselves as “payment”. The “industry” has seemingly acquiesced to such arrangements in the knowledge that publications can be seen as promotion for print sales, exhibitions and finding audiences for works that otherwise may have been left in a proverbial box at the back of the studio.

Much of the CRB project reflects a popular interest in realist photography that is not necessarily associated within the academy or related photographic learning. Nostalgia and localism play a huge part; the value of seeing the fabric of one’s past life through the eyes of another extends access to a wide audience. Although most content is from professional or “trained” photographers, we might understand that a portion of the work relies upon a relaying of the “everyday”, a photo-journalistic or “newsy” approach. There are also the more authored documents drawing upon the aesthetic legacies and concerns of the documentary genre. It is this crossover that presents a fascinating blend suggesting that content leads the way rather than any emphasis on particular sub-genres.

What is evident, looking through the display at The Photographers’ Gallery and the online shop, is that the project occasionally reads as both a celebration and a salvage ethnography of the near. London Street Markets 1960s–1970s (2020), Old Ladies of Whitechapel (2013), Sheffield Tinsley Viaduct (2013), Glasgow Steamies (2014) and so on; lives captured and presented joyously. Such works and others represent an enthusiasm for social realism that preceded (or ignored) any de-constructivist critique of documentary and held photography up as an uncomplicated social tool.

In this sense, nostalgia for the genre itself also plays a part in the appeal of CRB’s output, further defining the project, reconsidering the documentary medium itself as a particular movement at a particular time in history, alongside questions of the conditions that created such mass activity that largely involved photographing the lives of others. In this sense, one might squint and find a mass participation project by proxy, a culturally assimilated ethnography by many like-minded people who have shared similar photographic educations and happen to be born in the early to mid-20th century, figuring out their place in the world through the observations of others.

The legacies of this contribute to the enormous reach of CRB’s output, that could be easily edited and curated into larger narratives and publications of documentary approaches, based around geographical location, social thematics and so on. And with scale in mind, there are inevitable analogies and shared interests to be made with the Mass Observation Project or even the much-overlooked German and Russian located Worker Photography Movement, with, of course, significant differences regarding their origins, social histories and political contexts.

On the night of the private view, the exhibition space was continually busy, as the audience were involved in a brisk and satisfying material engagement with the works on show, handling, looking and putting back. Whilst the installation at the gallery will clearly be enjoyed, for logistical reasons it shows only 300 books whereas the upcoming show at Impressions Gallery, Bradford, will reveal 700. To see CRB’s output in its entirety would be an ideal (and conceptual) installation offering a monumental showcase to what is a monumental project.

One of documentary photography’s strengths is its ability to project social history. Arguably, a distrust of photography’s intersection with AI, for example, may embolden this, having a refreshed relative authenticity on a popular level at least (and, whatever happens, an interesting dialogue is about to ensue). The analogy with the Mass Observation Project, and its relatively low-key activities contemporarily, brings forward questions around the supply of work that CRB publishes and whether it might dry-up. I have a friend who mudlarks in the Thames, finding ancient artefacts, some of which are now in the Museum of London. We marvel at how, at each turn of the tide, new riches are given up, seemingly inexhaustibly. Photography, too, just keeps coming, but how does the production of modern social narratives, which most of us participate in with our regular uploads, fit into the documentary paradigm that is presented by CRB? The relocation of such vernacular work made continually on camera phones has similar but differing values. Enabling such egalitarianism would be a natural fit with the politics of this amazing project.♦

All images courtesy of Café Royal Books

Café Royal Books runs at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, until 2 June 2024.

—

David Moore is a photographic artist and Principal Lecturer at the University of Westminster, London, where he teaches on the Expanded Photography MA programme.

Images:

1-Amelia Troubridge, Motörhead, from Motorhead UK, 1997

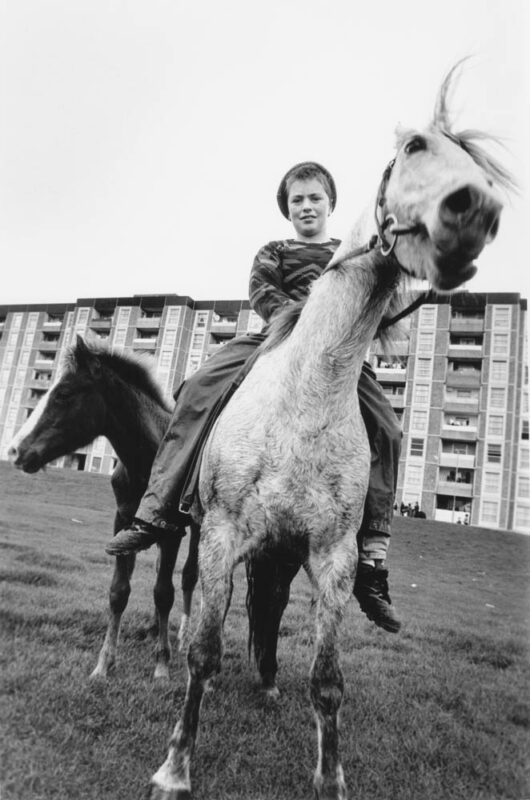

2-Amelia Troubridge, Urban Cowboys, from Urban Cowboys Dublin, 1996

3-From Being British 1975-2005 © Barry Lewis

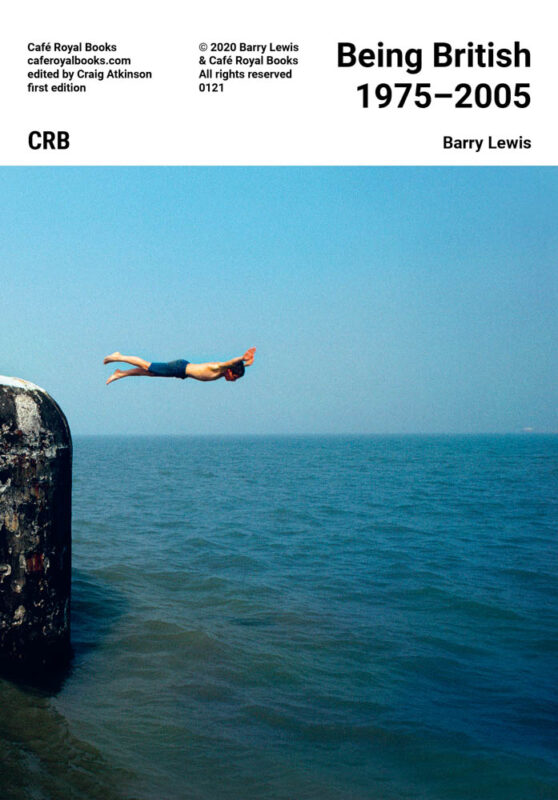

4-Cover of Being British 1975-2005 © Barry Lewis

5-Chris Miles, Musical Float. From Notting Hill Carnival, 1974

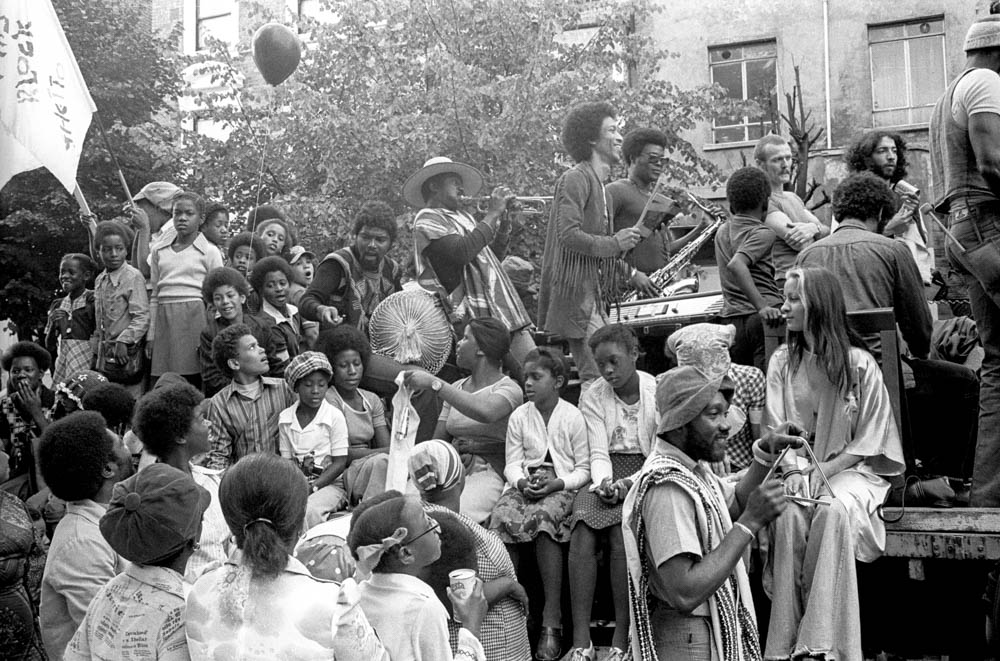

6-Cover of Parfett St Evictions, 1973 © David Hoffman

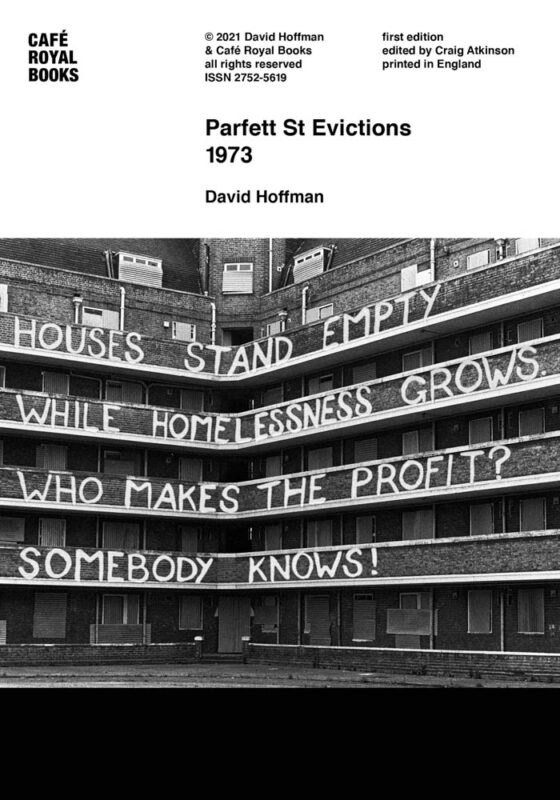

7-From Burnley 1970s © Dragan Novakovic

8-Cover of Black Power Black Panthers, 1969 © Janine Wiedel

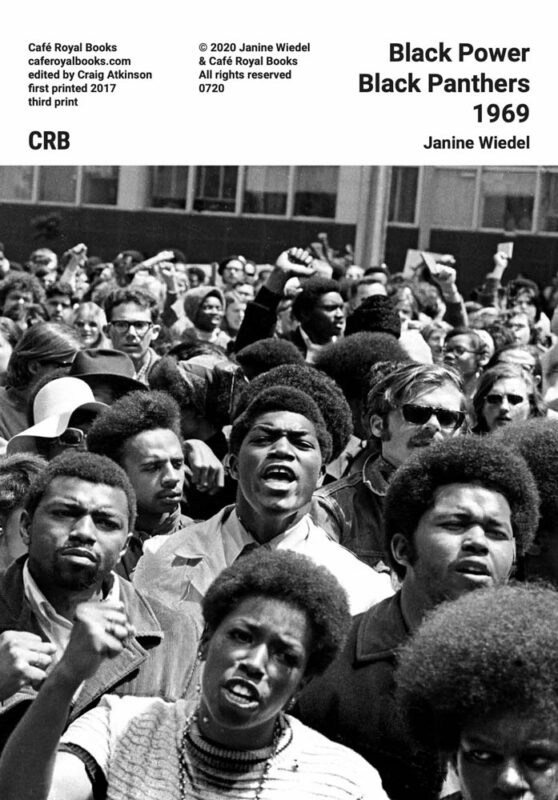

9-Cover of Football Fans, 1991 © Richard Davis

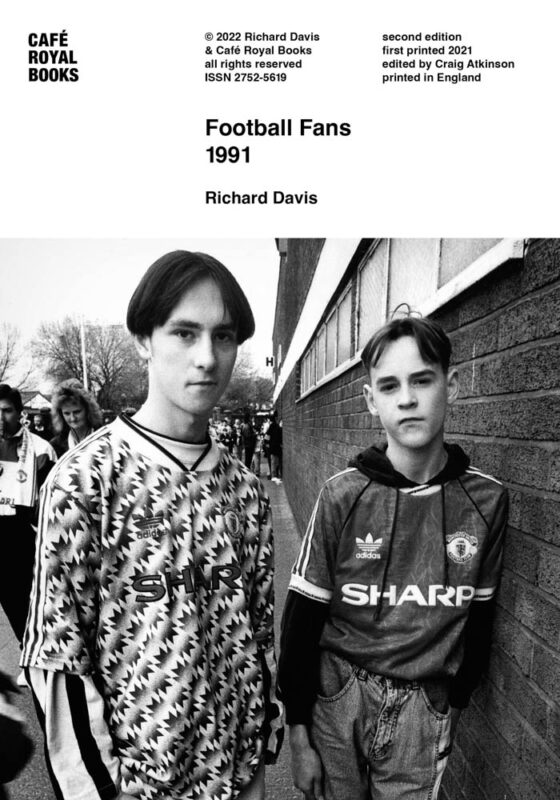

10-Cover of Early Colour, Hulme Manchester, 1985 © Shirley Baker

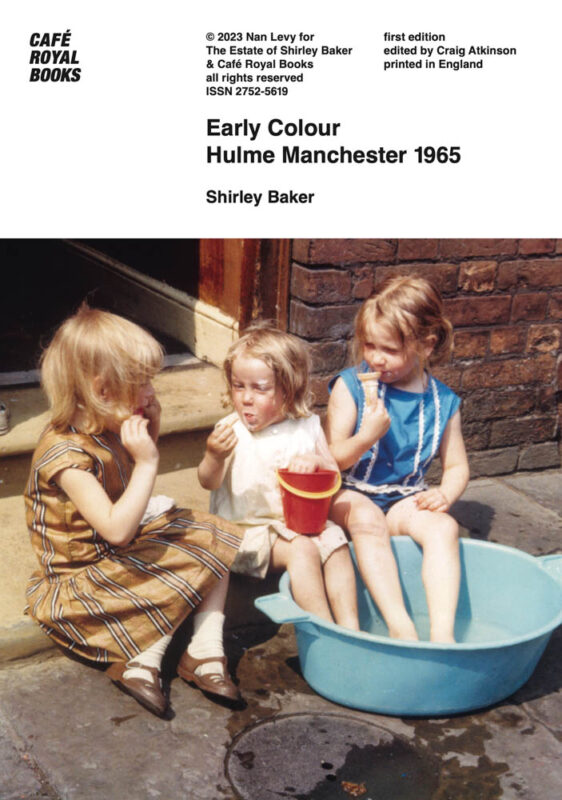

11-Cover of Northern Soul, 1993-96 © Elaine Constantine

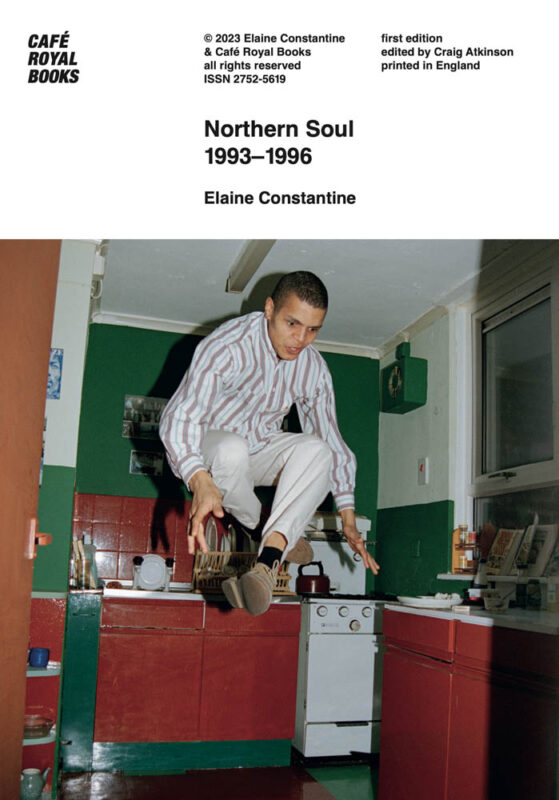

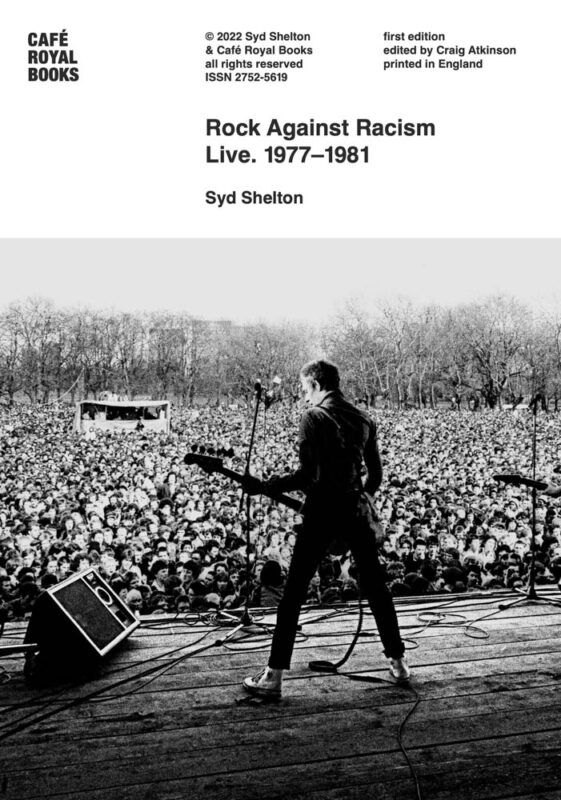

12-Cover of Rock Against Racism Live: 1977-1981 © Syd Shelton