Carrie Mae Weems

Reflections for Now

Exhibition review by Jermaine Francis

Carrie Mae Weems’ work has long questioned how the representation of the Black subject has historically reproduced racism and inequality. On the occasion of Weems’ first major UK solo exhibition, Jermaine Francis considers her distinguished opposition to racial violence and all forms of oppression to engage us in a dialogue about the Black experience and narratives of resilience in the US.

Reflections for Now, at the Barbican, brings together a collection of installations, film and photography by the artist Carrie Mae Weems. For over 30 years, Weems has employed the use of multi-visual disciplines to interrogate the image and its effects on the contemporary Black American experience. Furthermore, the exhibition asks us to consider the work beyond reductionist readings of identity, as Weems has herself written: ‘There are so many avenues of exploration in the work. […] There are ideas about beauty, how beauty functions in the work.’

The exhibition opens with a series of abstract images in Painting the Town (2021), made in the aftermath of the protests that erupted after the George Floyd killing in Minneapolis in 2020. Large-scale and tightly-framed, the photographs of boarded buildings appear to resemble the visual language of abstract expressionism, but flipped on its head, once the context is revealed. The colour blocks demonstrate to the audience an act of erasure: the removal of the evidence of the protesters’ words, which in turn serves as a metaphor for a wider denial. In addition, Weems also suggests another subject of erasure: Black abstract expressionist painters, such as Mary Lovelace O’Neal, whose contribution to the discourse of painting and wider culture have often been overlooked.

The gallery space becomes the battleground in which the agency of the Black woman is asserted. Whether she is in front of the camera or behind the camera, Weems, in the words of Hilarie M. Sheets, ‘us[es] herself as surrogate for all possessed women, controlling narrative both subject and photographer.’ In Roaming (2006), which ends the show, a solitary Black silhouetted figure appears engulfed by institutions, museums, galleries and architectural structures, made even more poignant by Weems’ evocation of Benito Mussolini’s Rome, a reminder of the aesthetics of fascist desires.

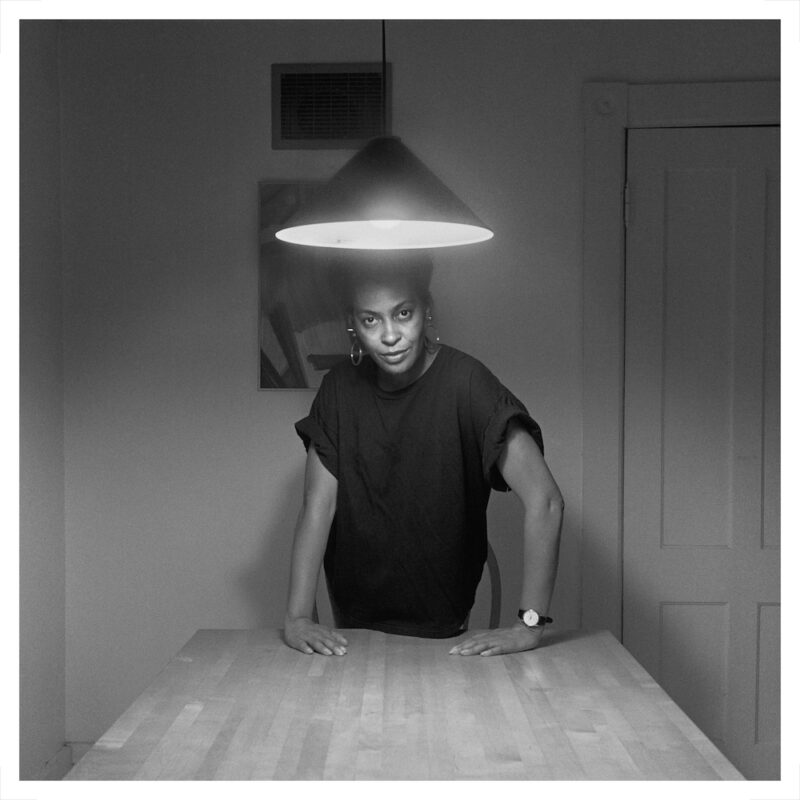

Kitchen Table (1990) is an epic series that flows through two rooms, disrupting the one-dimensional representation of the Black woman through the presentation of an unapologetically complex set of narratives by the sophisticated incorporation of performance, construction, text and the self-portrait. In these photographs, Weems is centre stage, presenting her own story. Unlike so many historical depictions of Black women, she demands agency from the viewer, whilst engaging us in a rich dialogue about relationships, race, misogyny, sex and camaraderie.

The amplification of the presence and resilience of Black women is everywhere in this exhibition, and felt no more powerfully than in the installation Case Study Room The portraits of Black Panther members such as Angela Davies and Kathleen Cleaver are presented equally with their male counterparts, their contributions celebrated.

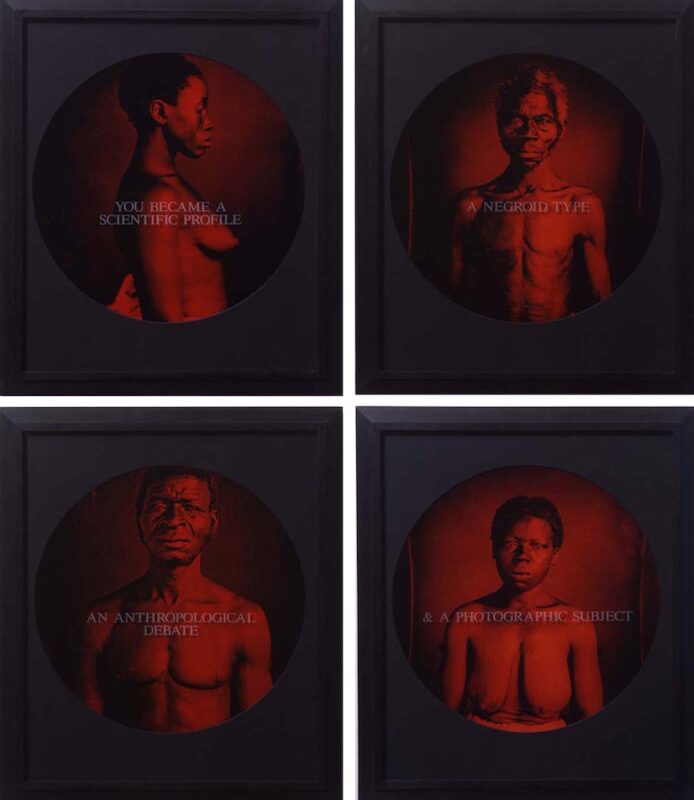

The exhibition takes us on another journey, one of dissonance and erasure that more directly addresses the issues around photography’s distribution and historical use. From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995–96) is a deeply moving and emotional work which deals with the concept of what Mark Sealy refers to as ‘racial time’. Weems asks us to consider ‘the photograph’s function as a sign within the historical conditions’ and how Black people have been historically represented.

The controversial Harvard daguerreotypes of Black slaves, now recontextualised with overlaid titles, proposes the process of dehumanisation, the photographs being complicit in the reinforcement of racial ideologies. It is further into the sequence that we are presented with the Gary Winogrand image of a white woman and a Black man, a couple, holding two chimpanzees. Some Laughed Long & Hard & Loud (1995–96) is the title, and Weems is asking us to consider this and the other images in the room in the context of ‘racial time’. It also calls to mind Jean-François Lyotard’s ideals of the sublime – ‘presenting the unpresentable’ – as well as the work of Alfredo Jarr, which employs aesthetics to unpack social injustices.

These avenues of exploration are what we are constantly asked to engage with throughout the exhibition. Articulating these overlapping themes and strategies most powerfully is The Shape of Things: A Film in Seven Parts (2021), a 45-minute-long panoramic video piece taking the viewer on a nonlinear journey through the history of the USA. Comprising a rich mosaic of archive material, news footage, noir, sound and soft monologues, it gives me a sensation similar to one I felt hearing Larry Heard’s Waterfall (1987). The panoramic screen dominates not just the room but also our eyeline, conjuring parallels to Weems’ protagonist in Roaming. There are particular scenes that are distinctive, a sumptuous frame of a Black woman fixing her gaze towards us, while papers, documents and newspapers cascade around the figure. The appearance of multiple female figures, and one male who dances in the rain, can be read as a sense of defiance but also healing. Early on, we experience a sensation of dissonance, with the screen split vertically to project repeated 1960s archival footage of a Black protest. On the right, a white crowd directs their anger to the image on the left, where a Black man verbally retaliates. A monologue in a male voice informs us that, in the end, they stopped trying because some people cannot be convinced to change.

From the multi-image work, The Push, The Call, The Scream, The Dream (2020), certain images haunt my mind. The first is a portrait of two women side by side, one young and Black, the other white and wearing the uniform of the Ku Klux Klan. The other is of a young boy crying at a funeral, which takes me to a place where I contemplate various events that have happened, and continuous cycles of hate.

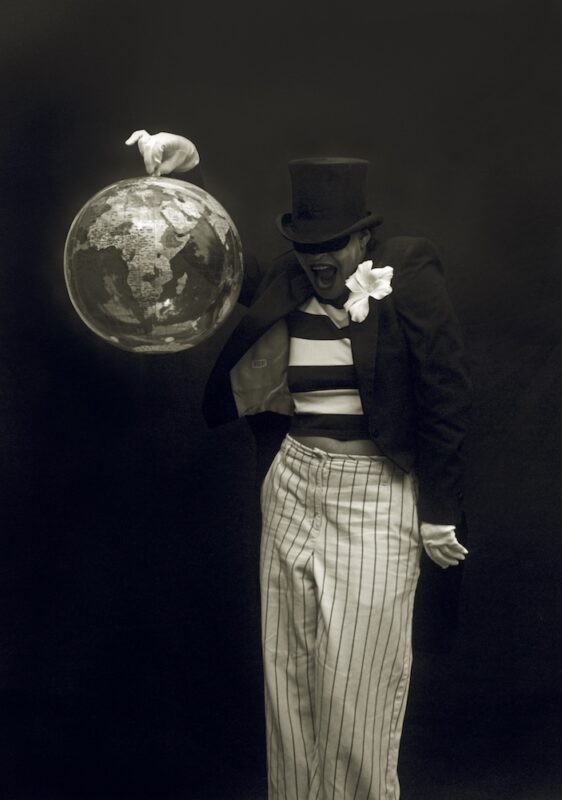

We are presented with scenes of modern tragedies in which desperate people attempt to flee wars, famines and droughts: news footage of Afghani families trying to board the disembarking planes, refugees fleeing on boats, combined with ladies of leisure drinking tea from a bygone era; archival films of old comedy circus performances, devious clowns, alongside views of the Capitol riots. These are the consequences of this modern day pantomime and Weems asks us to reflect on America’s polarisation and the collateral damage being the Black demographic. This is reinforced by a scene in which a Black man runs in front of three clocks all set to three o’clock, whilst a voice undulates the dream-like sequence: “commemorating all who have fallen, and all those who have endured, commemorating every Black man who sees age 21…”

The words speak of the other reality; of the Black and brown victims, repeatedly killed at the hands of those in positions of authority, who wear the same uniform as Goodman. In the hypnotic darkness of It’s Over – A Diorama (2021), an installation which I would describe as a memorial to the fallen, Weems presents a sense of hope. We are given propositions by a male voice whilst a camera sweeps over illuminated individuals in a crowd. A kind of manifesto exploring how citizens in the US can maybe find a better way of living, the film ends with the image of Weems swinging to the Jimmy Durante song, Make someone happy. Reminiscent of circus acts, it all feels appropriately bittersweet.

I often found myself questioning whether the wall texts need to be so descriptive of Weems’ intentions, yet this is a criticism that could be levelled at any exhibition. Maybe I wish it was left more to the viewer than some institutions might like to imagine, or maybe what’s most important is to experience a journey, one that tries to engage us in a dialogue about the Black experience and resilience in the US. In a world in which dialogue appears to be under attack, maybe we need this more than ever. ♦

All images courtesy the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York / Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin and the Barbican, London © Carrie Mae Weems.

Carrie Mae Weems: Reflections for Now runs at the Barbican, London until 3 September 2023.

—

Jermaine Francis is a UK born and London based photographer and visual artist. Originally from the West Midlands, his work explores power, space, identity, social and political issues. He has exhibited at the ICP New York, Photo Oxford, Saatchi Gallery, Galeriepcp, and the Centre for British Photography. He co-curated Notes on a Native Son at Peckham 24 2023 together with Emma Bowkett.

Images:

1- Carrie Mae Weems , Untitled (Woman Standing Alone) from Kitchen Table Series, 1990

2- Carrie Mae Weems , Untitled (Woman and Daughter with Make Up) from Kitchen Table Series, 1990

3- Carrie Mae Weems , You Became A Scientific Profile; A Negroid Type; An Anthropological Debate; and & A Photographic Subject from From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, 1995-96

4- Carrie Mae Weems , If I Ruled the World, 2004

5- Carrie Mae Weems , The Assassination of Medgar, Malcolm and Martin from Constructing History, 2008

6- Carrie Mae Weems , Still from Cyclorama – The Shape of Things: A Video in 7 Parts, 2021

7- Carrie Mae Weems, The Louvre from Museums, 2006

8- Carrie Mae Weems , Philadelphia Museum of Art from Museums, 2006

9- Carrie Mae Weems , When and Where I Enter — Mussolini’s Rome from Roaming, 2006

10- Carrie Mae Weems, The Edge of Time — Ancient Rome from Roaming, 2006

11- Carrie Mae Weems , Lincoln, Lonnie, and Me — A Story in 5 Parts, 2012