Top 10

Photobooks of 2017

Selected by Tim Clark

An annual tribute to the most exceptional photobook releases from 2017 – selected by our Editor in Chief, Tim Clark.

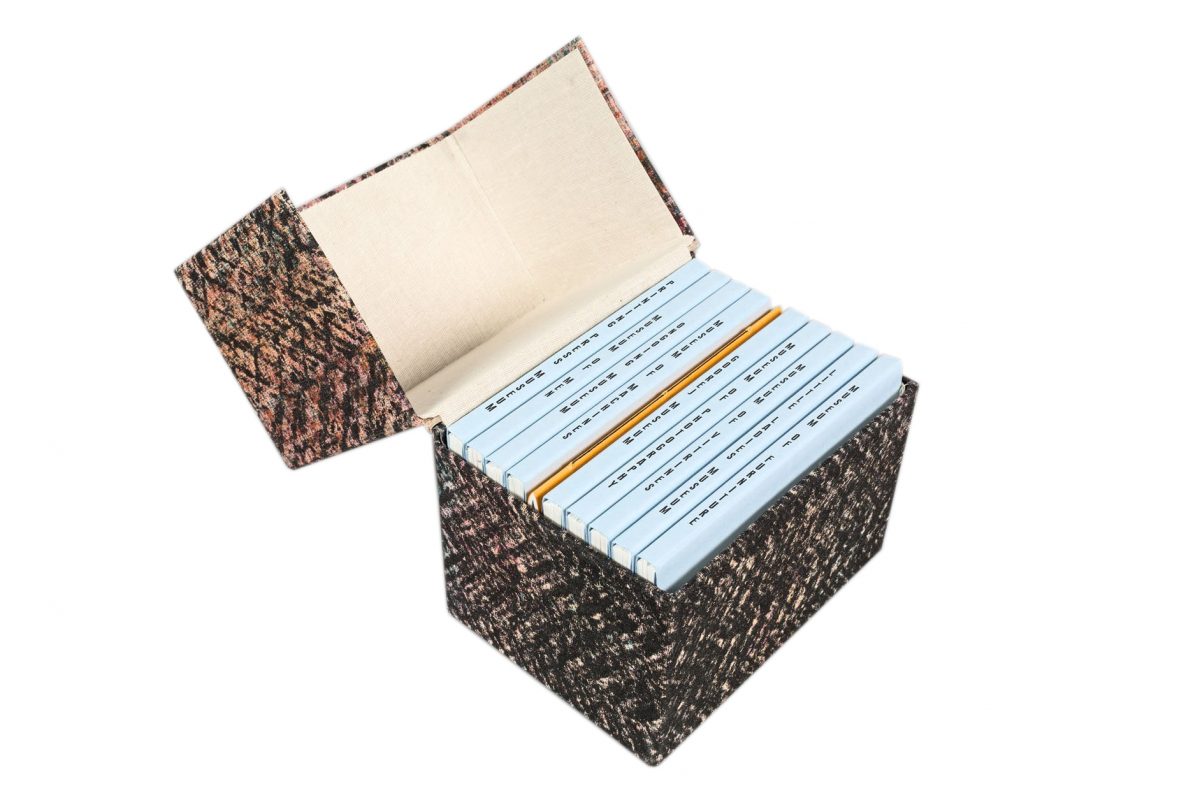

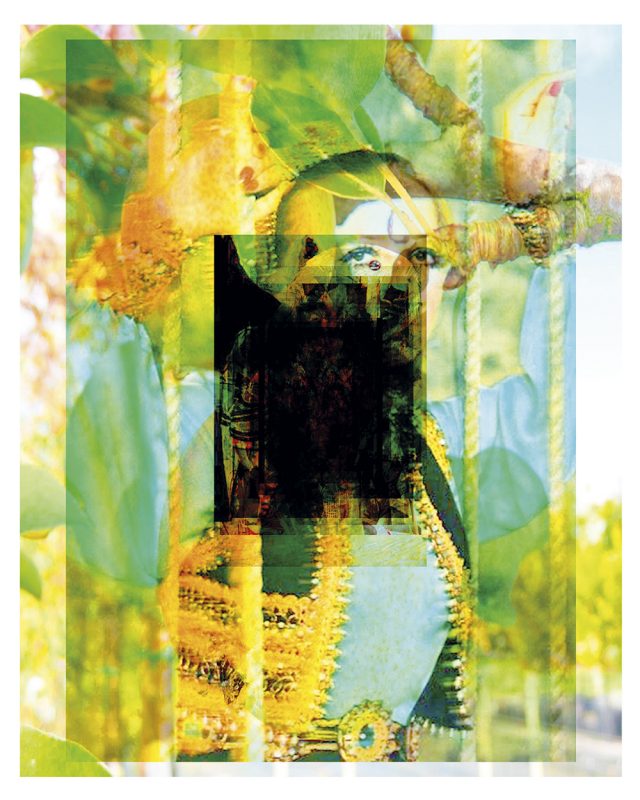

1. Dayanita Singh, Museum Bhavan

Steidl

Dayanita Singh continues to play her part in freeing the photobook from orthodoxy with Museum Bhavan. This collection of multiple bodies of work, presented as 9 miniature book ‘museums’ offers a joyous experience, where layers of discovery result from folding out the accordion-like strips which Singh welcomes viewers to curate and install as they choose. The images contained within them run the gamut of Singh’s career – from 1981 to the present – cataloguing everything from machines and furniture to more lyrical explorations of womanhood in ‘Little Ladies Museum’, among others. There is a sense of deep materiality in Museum Bhavan, not to mention an appreciation for both paper and the haptic qualities of the book object. A worthy winner of Photobook of the Year at the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation Awards 2017.

2. Nicholas Muellner, In Most Tides An Island

Self Publish, Be Happy Editions

Nicholas Muellner also expands the possibilities of what the photobook can be. Deftly fusing image and text, In Most Tides An Island is a poignant exploration of love, desire and loneliness in the digital age. Photographed in the Black Sea regions of Russia, Ukraine and Russian-occupied Crimea, and on the islands of Kronstadt, Russia and Little Corn in Nicaragua, the project has been guided by dual impulses: to bear witness to the real lives, stories and environments of closeted gay men in provincial Russia – longing for connection yet prevented from openly demonstrating their feelings – and the imagined tale of a solitary woman on a Caribbean island. At once travelogue, document, autobiography and fictional construction, In Most Tides An Island resists any straightforward definition. Its parallel stories are structured into 12 chapters, over the course of which the viewer–reader is taken on a dizzying descent into the lonely, unintended consequences of our isolated yet hyper-connected lives.

3. Simon Roberts, Merrie Albion: Landscape Studies From A Small Island

Dewi Lewis Publishing

More conventional in format but relying on utterly captivating landscape photography is Simon Roberts’ Merrie Albion: Landscape Studies From A Small Island. Released in the wake of the nationalist triumph of Brexit, this brilliant new book takes the temperature of the UK, offering insights most necessary into notions of identity and belonging and, specifically, what it means to be British at this significant moment in contemporary history. With his customary elevated perspective and tableaux style, we oversee views of places and the people that populate them to form a survey: not only of spaces used for leisure and cultural activity but also subjects and events that can now be viewed as defining locations in recent times, such as the London 2012 Opening Ceremony or Greenfell Tower. A real socio-political mood piece, the power and urgency of which reminds us why Roberts is regarded as one of the leading UK photographers working today.

4. Henk Wildschut, Ville de Calais

Self-Published

Made in the French harbour city of Calais, Henk Wildschut’s book chronicles the rapid transformation and decline of a makeshift village, where thousands of refugees and migrants were camped in the hope of crossing the channel into the UK – only to be eventually ousted by the authorities in October 2016. Winner of Les Rencontres d’Arles Author Book Award 2017, Ville de Calais lifts the lid on the visible mass of shacks and shelters that sprang up to form a temporary city with its own collection of houses, restaurants, churches, mosques and libraries. Designed by Robin Uleman, this is a complex, multi-layered book that begins with studies of informal migrant settlements located in woods and then shifts its focus onto the area referred to in the media as the ‘Calais jungle’. The course of time becomes integral through sequencing of images that index the development of the camp, while its inhabitants are admirably pictured with dignity and a respect for their strength and resourcefulness. Ville de Calais raises the bar for all work on the migrant crises that follows.

5. Laia Abril, On Abortion: And The Repercussions Of Lack Of Access

Dewi Lewis Publishing

True to its title, Laia Abril’s latest book offers a deeply affecting study of the risks and repercussions of women’s access to safe, legal or free abortion – or lack thereof. The product of extensive research, On Abortion brings to light terrible truths by means of portraits, testimonies and ephemera to both document and conceptualise the ongoing erosion of women’s reproductive rights. Provoking debate around issues of ethics and morality, or making – in that hackneyed phrase – the invisible visible, the Barcelona-based photographer once again boldly squares up to certain taboos and stigmas with great compassion and empathy. Designed by Ramon Pez, and published by Dewi Lewis, it’s heartening to see the trio’s commitment to resisting this moment of revised misogyny that we are living through, reminding us that every year some 47,000 women die annually from botched abortions.

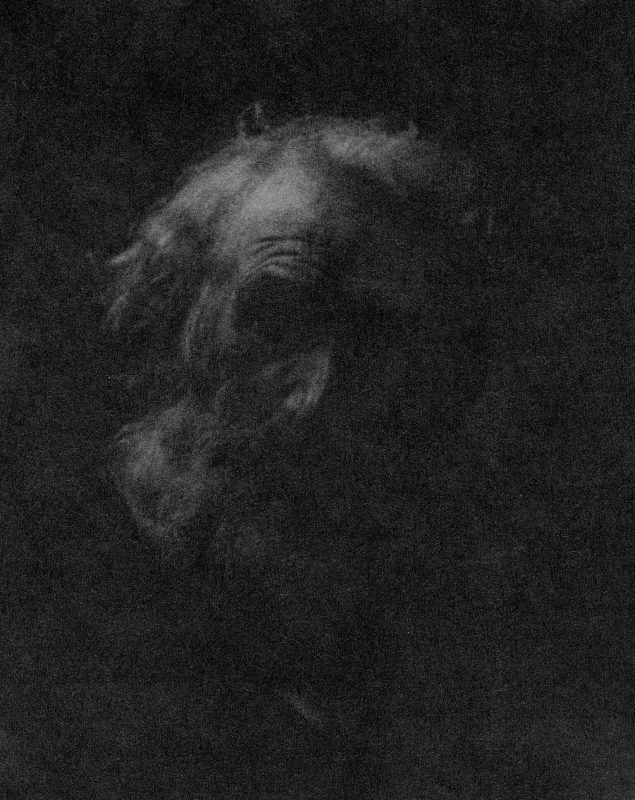

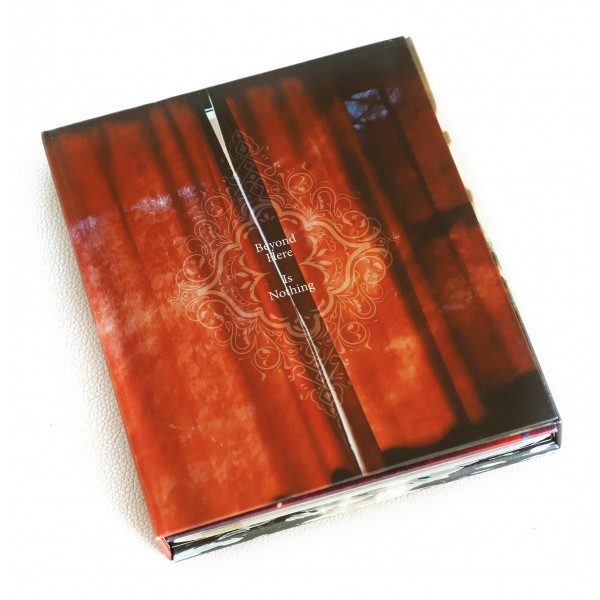

6. Sandrine Lopez, Moshé

L’Editeur du Dimanche/The Sunday Editor

A chance encounter with an 89-year-old Rabbi on the streets of Brussels serves as the starting point for Sandrine Lopez’s creative odyssey. Following a few, initial spontaneous portraits of Moshé, the central protagonist who the publication is named after, the French photographer engaged in weekly rituals with her subject over a period of two years. Visiting his house to provide care, enjoy his company and give baths, Lopez formed a touching relationship, and has come away with a striking set of photographs that are at once tender and terrifying. Unremitting in its examination of the fragility and beauty of a human body, Moshé speaks to notions of decay, impermanence, and also, crucially, about the nature of vitality in the face of the black portal beyond. With its suedette cover – complete with an intricate debossing of Moshé’s face – Lopez’s debut book dazzles in sensuality and existential query, providing a noteworthy contribution to this year’s offerings.

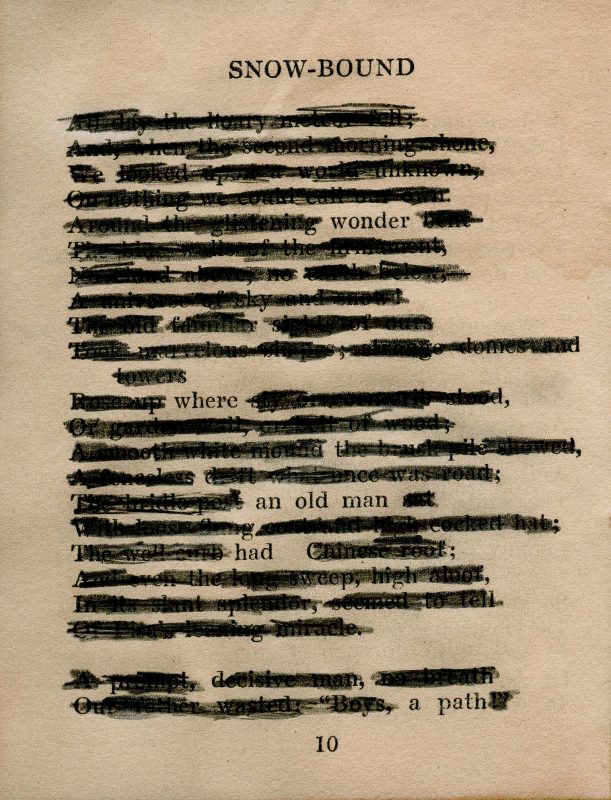

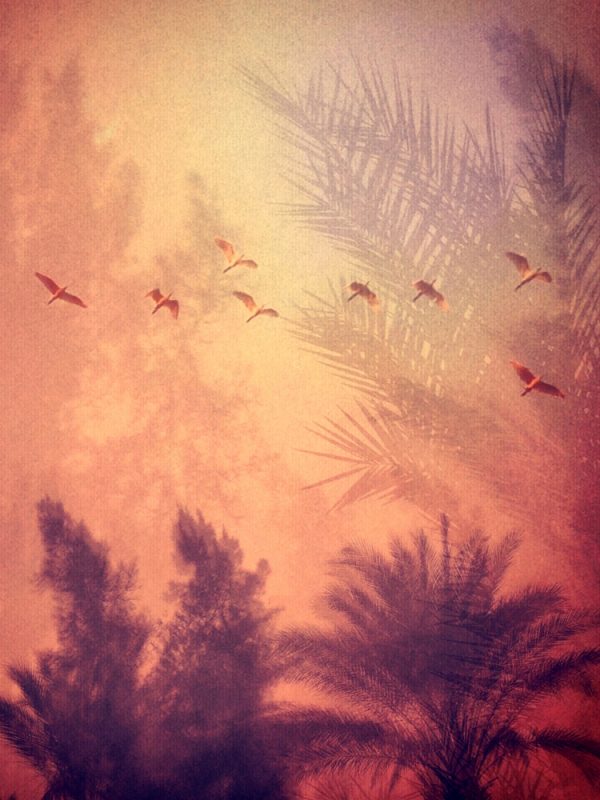

7. Edgar Martins, Siloquies and Soliloquies on Death, Life and Other Interludes

The Moth House

Produced in collaboration with the Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences in Portugal, Siloquies and Soliloquies on Death, Life and Other Interludes is born out of a frustration with photography’s inability to show the nature of death, as opposed to the media’s glorification of the gory and the bizarre. Contemporary depictions tend to focus on spectacle, rather than attempt to create the space to encourage an understanding of its causes, contexts and consequences. Edgar Martins seeks to bring the latter to the fore. Dealing with violent death and, in particular, suicide, the he meditates on the often unforeseeable but always inevitable nature of mortality. He investigates its legacies through the depiction of material evidence – from extracts from suicide notes, to press photographs reporting family murders to photographic records of deceased persons’ belongings. A kind of conceptually-driven photography masterfully pairing text and image to explore the contradictions and problems inherent in the depiction on death, while also reflecting on language and semiotics. Martins shows us he is as much an accidental theorist as a photographer.

8. Debi Cornwall, Welcome to Camp America

Radius Books

Following her 12-year career as a wrongful conviction lawyer, Debi Cornwall’s practice as a photographer is informed by experiences of representing innocent DNA exonerees, which she channels into empathetic and, at times, darkly humorous photographs that comment on mechanisms of state control. Welcome to Camp America is a weighty tome that has layers upon layers of images of the spaces and surfaces of the Guantanamo Bay, complemented with classified government documents as well as first hand accounts. It is also studded with studio photographs of absurd merchandise available to buy from the detention centre’s very own Gitmo gift shop, including “I Love Guantanamo Bay” t-shirts for toddlers and high-top Velcro “Maximum Security” shoes. Text excerpts from prisoners and military personnel in both English and Arabic also run throughout the book, rounded off perfectly by searing essays from Moazzam Begg (a British-Pakistani man held in extrajudicial detention by the US government) and Fred Ritchin. A rivetting insight into the Kafkaesque qualities of this infamous facility to attend to the details of the West’s military-industrial complex, post-9/11.

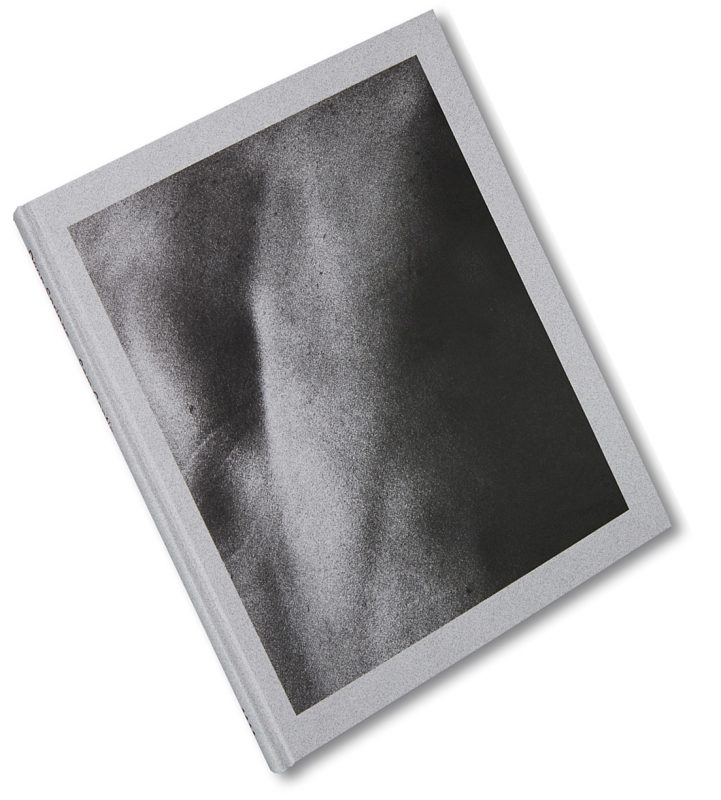

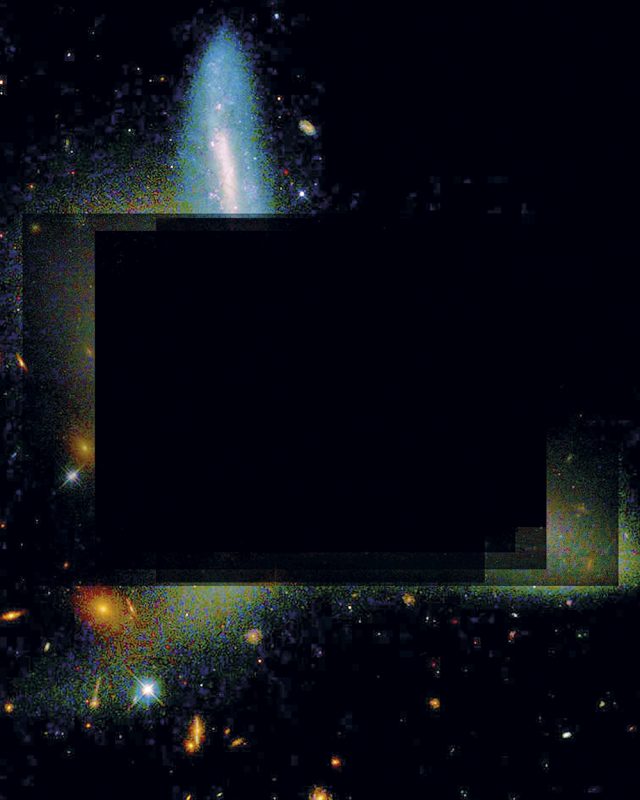

9. Giorgio di Noto, The Iceberg

Edition Patrick Frey

Photobooks don’t come any more obscure than this. In The Iceberg, Giorgio di Noto’s mysterious publication, the Italian artist cleverly explores how the Internet’s deep web has served to facilitate a ‘lawless no-man’s land, only accessible using specific software, where anything goes and nothing is traceable, and where illicit online businesses proliferate.’ It is said that this represents 90% of all net usage, yet whose contents are not indexed by any standard web search engines. As such, The Iceberg features an array of both stock imagery and poor quality photographs appropriated from countless advertisements for drug sales, designed to engage prospective clients’ attention. Curiously, the book comes with a torch fitted with an ultra violet bulb in order to view these original photographs, since they are invisible under normal light conditions. Evoking the practice of drug enforcers looking for traces of narcotics, this is a bold and experimental photobook project that pursues the anonymity and temporary nature of illegal deep web imagery – and celebrates it all the same.

10. Susan Bright, Feast for the Eyes: The Story of Food in Photography

Aperture Foundation

As food photography histories go, Susan Bright’s is of the highest and most delectable order. The renowned writer and curator has amassed her extensive research into the subject for this sizeable publication with Aperture Foundation. Tracing its development from the advent of the photographic medium to the present day, Feast for the Eyes features work from the likes of William Henry Fox Talbot through to Daniel Gordon and Rinko Kawauchi. Illustrated primarily through examples of still-life and fine art photography Feast for the Eyes also looks at the range of different applications and encounter in which food appears – such as fashion photography and cookbooks – to delve into the political, aspirational, symbolic and national dimensions of the genre. Insightful, immersive and extremely aesthetic, at the very least Feast for the Eyes is a great reminder of the manner in which photography touches every aspect of our lives. ♦

—

Tim Clark is a curator, writer and since 2008, has been Editor in Chief and Director at 1000 Words.