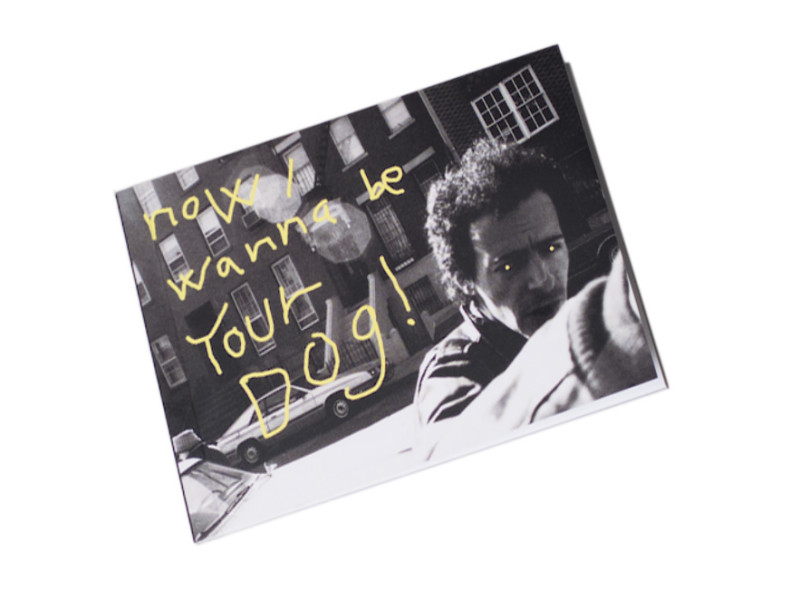

Gregory Halpern

ZZYZX

MACK

There is a place deep within the Mojave Desert, around 100 miles southwest of Las Vegas, called Zzyzx. The name was coined in the 1940s by Curtis Howe Springer – a radio evangelist and self-affirmed doctor who opened a health spa of the same name on the land. Springer – who liked to refer to himself as an “old-time medicine man” while others felt that “quack” was more fitting – was a regular chancer. Bottling water from nearby springs and knocking together potions that were really nothing more than celery and parsley juices, he claimed they were cures for any number of ailments. Zzyzx began in Springer’s mind, and journeyed into a real place over time. He named a road leading to the resort ‘The Boulevard of Dreams’.

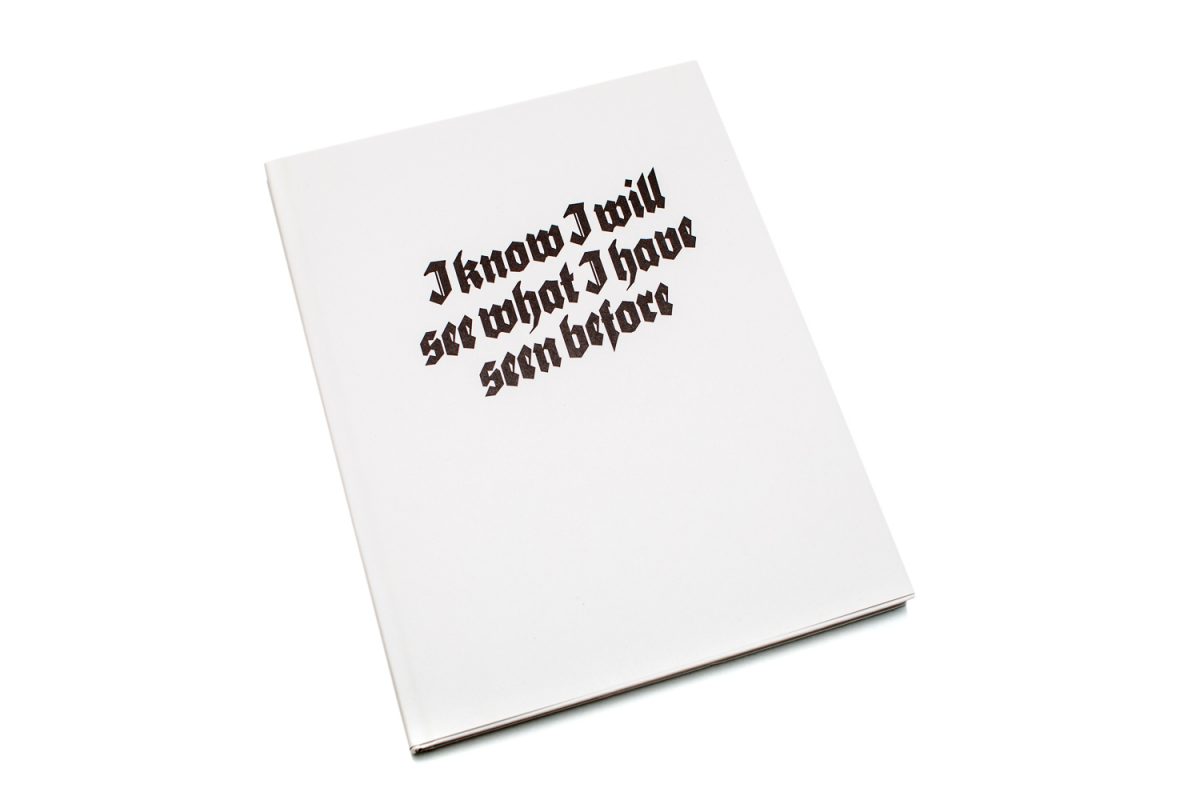

Something about the story of Zzyzx conjures up images of a young Sissy Spacek, arriving at a mysterious health spa in a small, dusty Californian desert town in 3 Women. Interestingly, beyond it’s setting, 3 Women is a film that is said to have come to its director, Robert Altman, in a dream, and he chose to pursue it without ever fully understanding what it was. Dreams, then, are a recurring theme, as Gregory Halpern’s own ZZYZX comes from a similar place, and he too saw a version of the bizarre dystopia we see in this book, fragmented in his dreams through time. Piecing together images of real people, and real scenes he reconstructed the place that had existed only in his mind. A fiction that made it’s way into reality.

ZZYZX traces a path that begins in the desert east of Los Angeles, moves through the city and ends up at the Pacific. Halpern uses the iconic idea of the journey West – embarked upon by countless artists and writers before him – as the symbol of a voyage to a better life, and a new start. California, in all of its sublime, inconceivable beauty is often seen as the embodiment of the American Dream – a brilliant, psychedelic, intensely dazzling place. But the brighter the light, the deeper the shadow. Los Angeles is also a fractured, profoundly devastating place. Where there is Hollywood there is skid row not so far away. Halpern’s LA makes your head swirl, oscillating somewhere between the two.

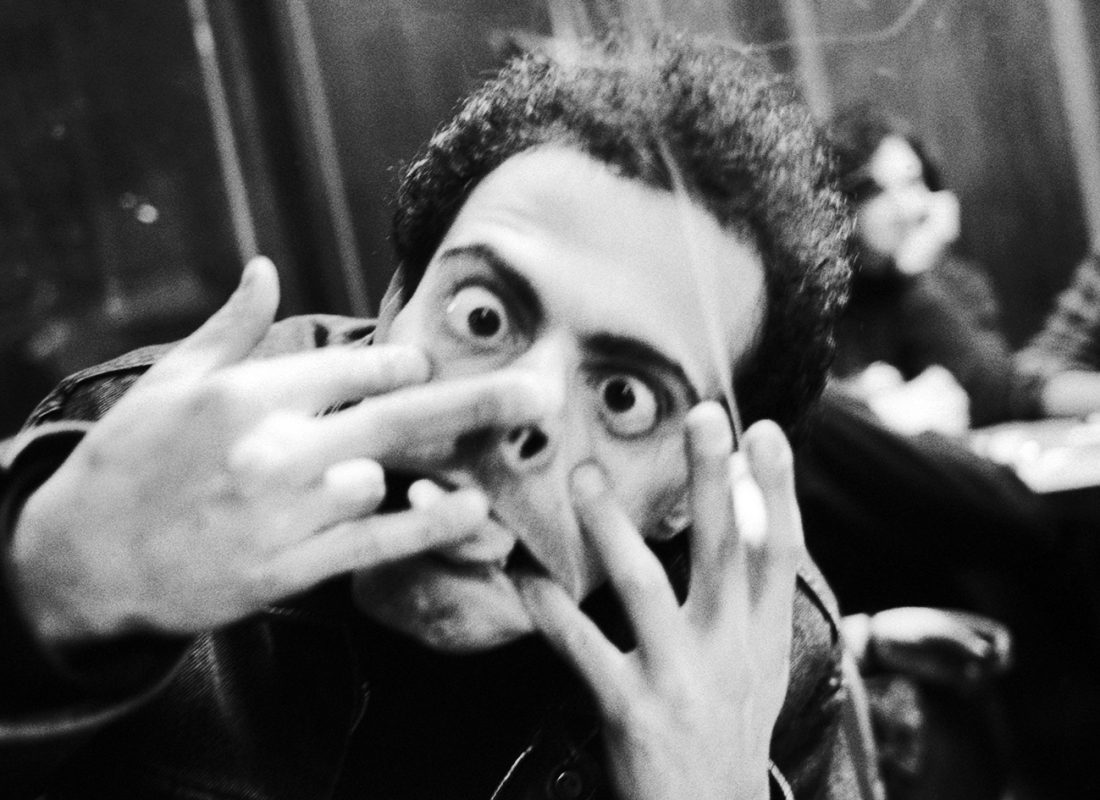

The book opens with the image of a hand with stars drawn upon it, reaching out of the darkness, palm illuminated to the sky. This image sets the chimerical tone of the book: sometimes the scenes we see are scorched in the blinding midday sun, while at other times we survey the city from the shadows. People, places and animals eclipse in and out of vision. The individuals who appear in Halpern’s photographs are often those who exist on the edges of society, and the view we are given as the reader reflects that. Almost always, the subject of the photograph is out of reach, seen from a distance, and obscured by branches or fences. Halpern’s portrayals of the people he meets are touching and very human – a particularly resonant photograph depicts a laughing woman, resting her head in the hands of another.

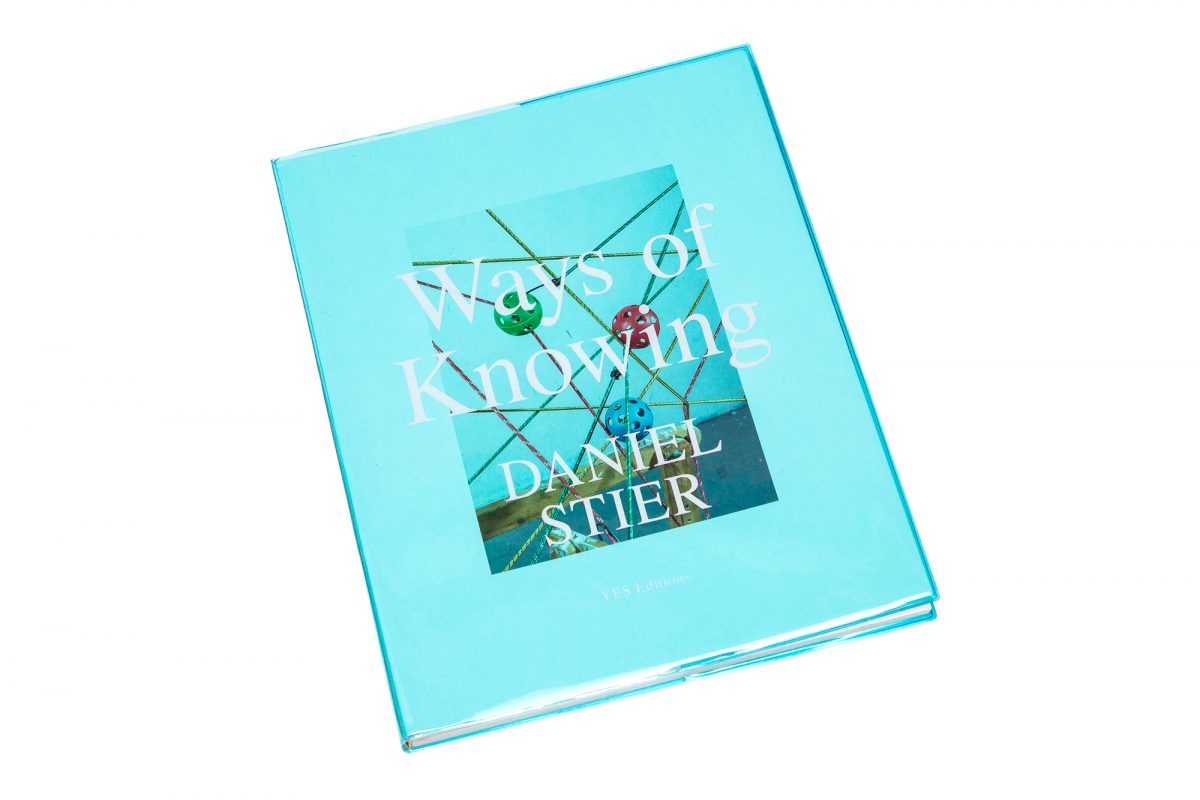

In the colophon, Halpern thanks Jason Fulford for his formative edit of the work, and that makes a lot of sense, as the images speak to each other in ways that are, at times, quietly reminiscent of Fulford’s own brand of image-editing. Subtle connections based on form and colour and symbol emerge between scenes. A cluster of criss-crossing branches gives way to the intersecting lines of a stairwell. A man, jaw agape and front teeth missing, appears opposite a shattered windscreen, it’s arch echoing the curve of his mouth. Everything leads from one thing to another.

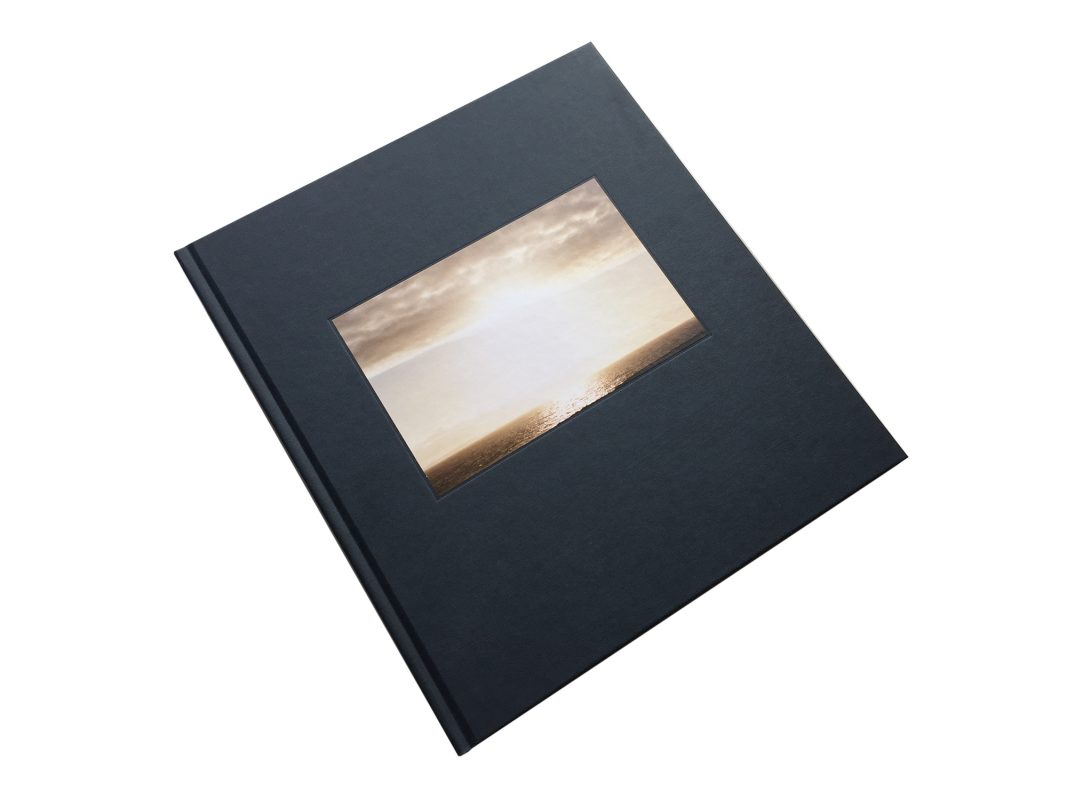

There is a constant sense of movement in ZZYZX, and the book carries us forward at an uneasy pace. With flashes of characters and quiet moments, it’s something akin to somnambulation. As Halpern sweeps across the city, things seem to get bigger – a small fire as a book burns on the beach later gives way to a forest blaze, pushing plumes of smoke across the sky. It always seems to be teetering on the brink here. Are things about to collapse? Halpern has recently said that in LA it feels like the world is always, slowly ending. Pathways, freeways and stairs recur throughout the book – ways in and ways up. Furthermore, Halpern wanted for there to be something biblical about this project, and certainly it feels like his pilgrimage. His attempt to distill Los Angeles – this terrifying, awful, beautiful, sprawling, almost mythical city – and everything that goes on inside of its parameters is exquisite and at times, painful. Towards the end of the book, Halpern moves back out, across sea and land. The penultimate image he offers us is phantasmagoric, of two overlapping squares of light falling across the sand. The place we saw, if only for a while, disappears, shimmering in the evening light. ♦

All images courtesy of MACK. © Gregory Halpern