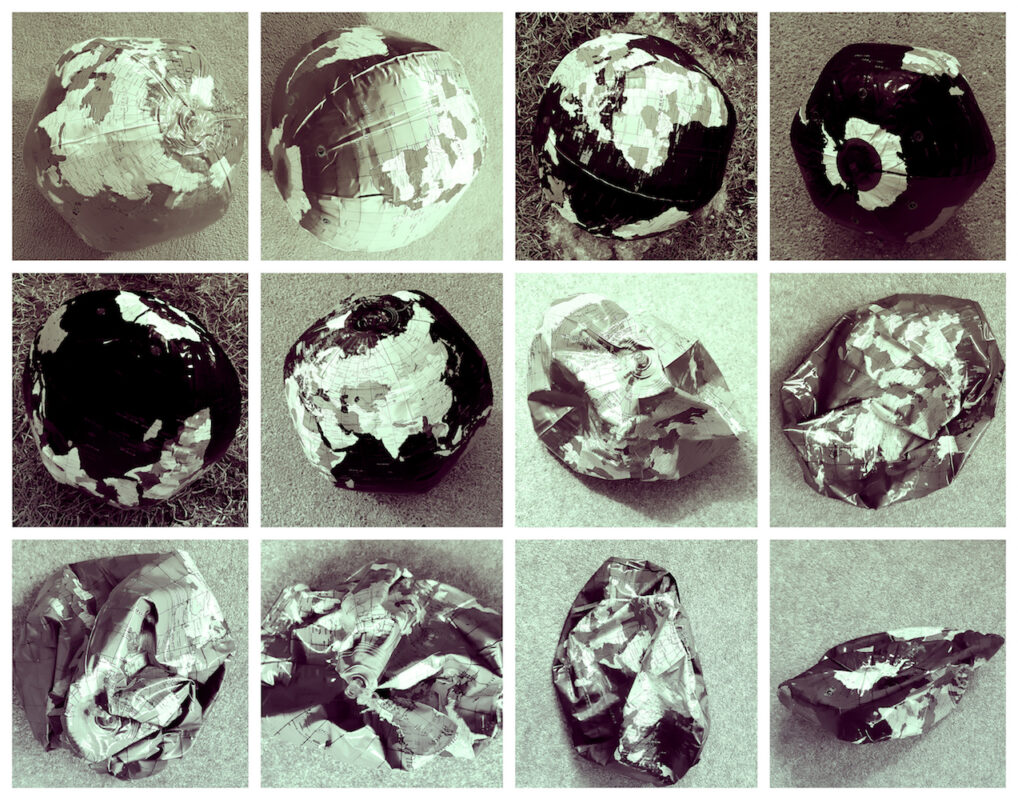

Curator Conversations #15

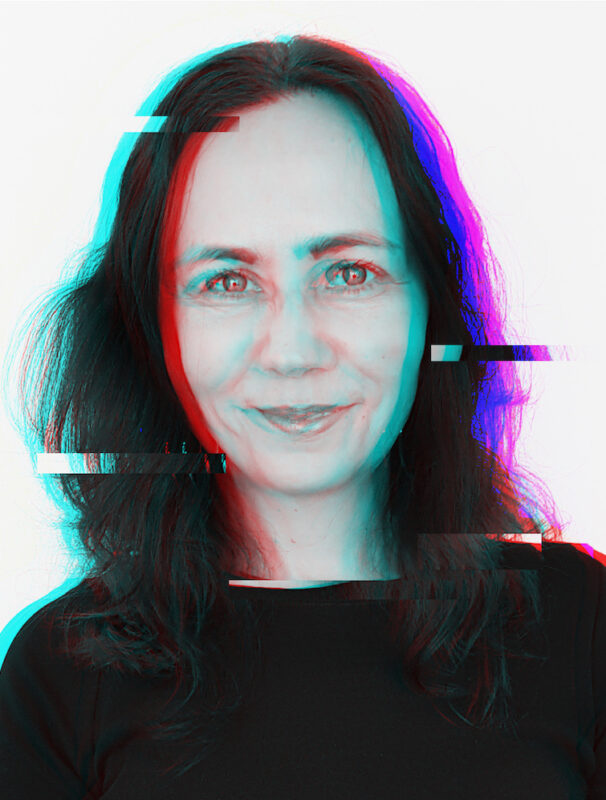

Renée Mussai

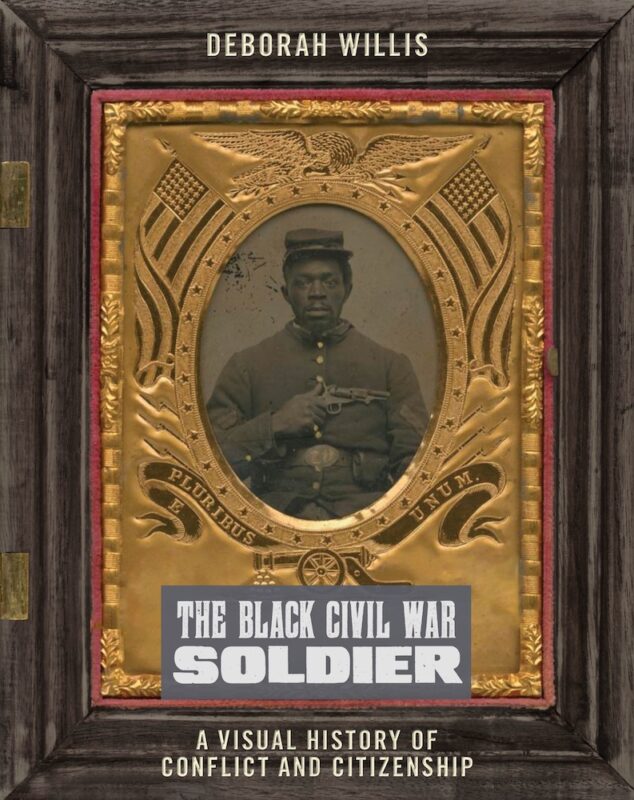

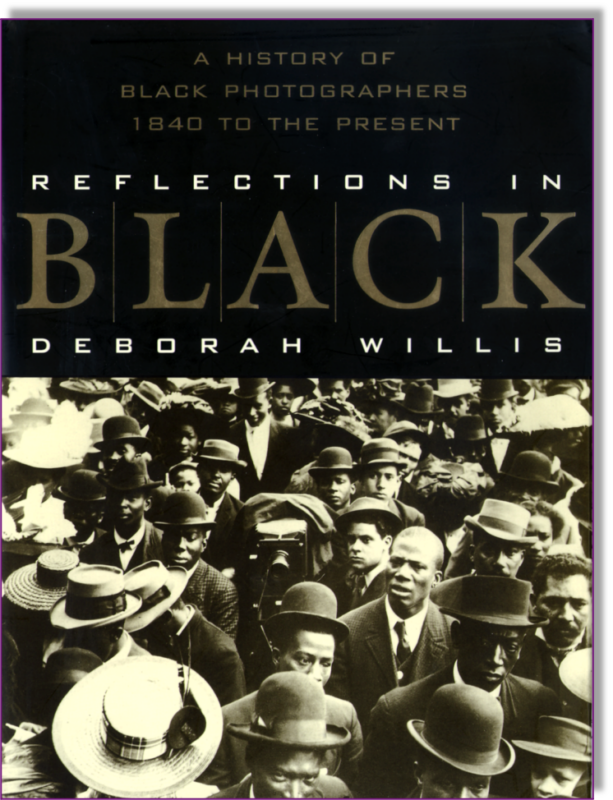

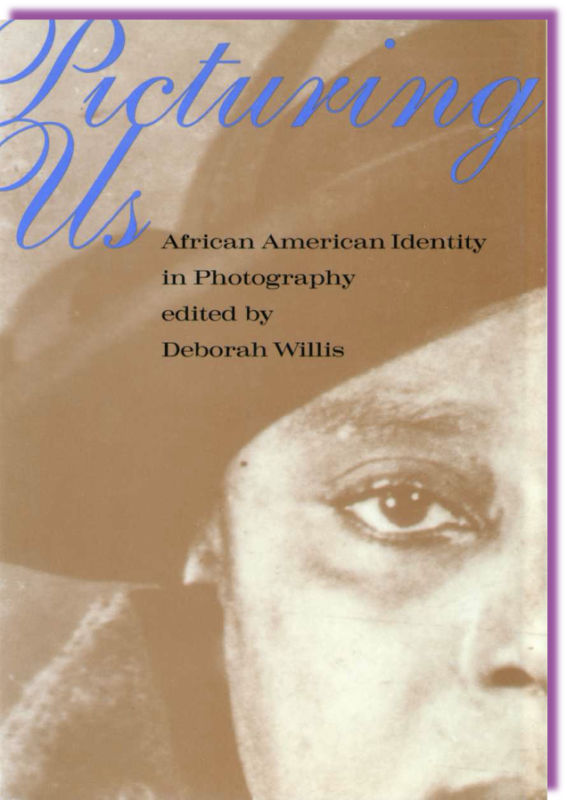

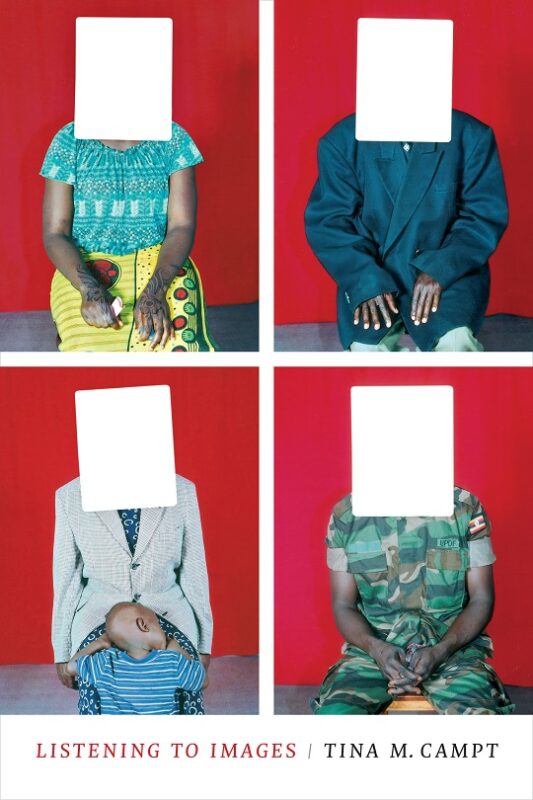

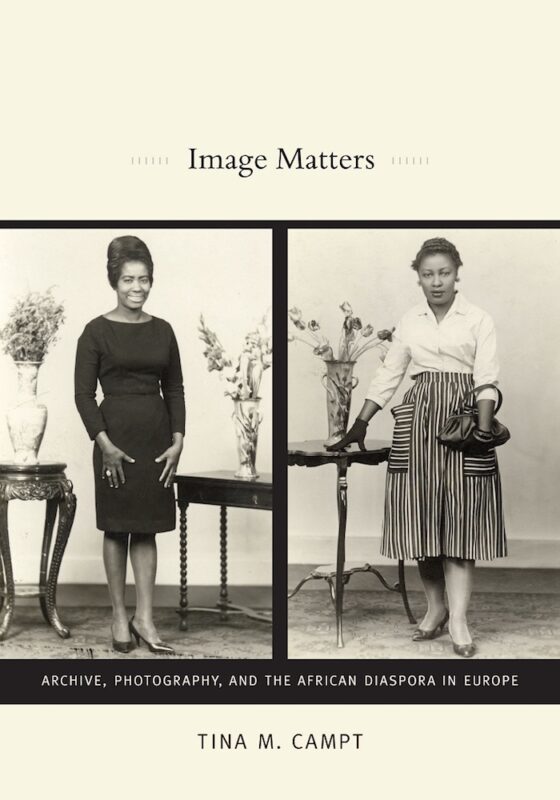

Renée Mussai is Senior Curator and Head of Curatorial & Collections at Autograph, London. Mussai has organised numerous exhibitions in Europe, Africa and America, and over the past few years curated a series immersive gallery installations with contemporary artists, including Zanele Muholi’s Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness (2017–present), Lina Iris Viktor’s Some Are Born To Endless Night — Dark Matter (2019–21) and Phoebe Boswell’s The Space Between Things (2018/19). Other previous monographic exhibitions include Aida Silvestri’s Unsterile Clinic (2016), Miss Black & Beautiful (2016), and James Barnor: Ever Young (2010). With Mark Sealy, she has co-curated group and solo exhibitions such as Omar Victor Diop: Liberty/Diaspora (2018), Making Jamaica: Photography from the 1890s (2017), Congo Dialogues – When Harmony Went to Hell (2015), Rotimi Fani-Kayode (2011), and W.E.B. Du Bois: The 1900 Paris Albums (2010). With Bindi Vora, she recently curated Lola Flash: surpassing (2019) and Maxine Walker: untitled (2019).

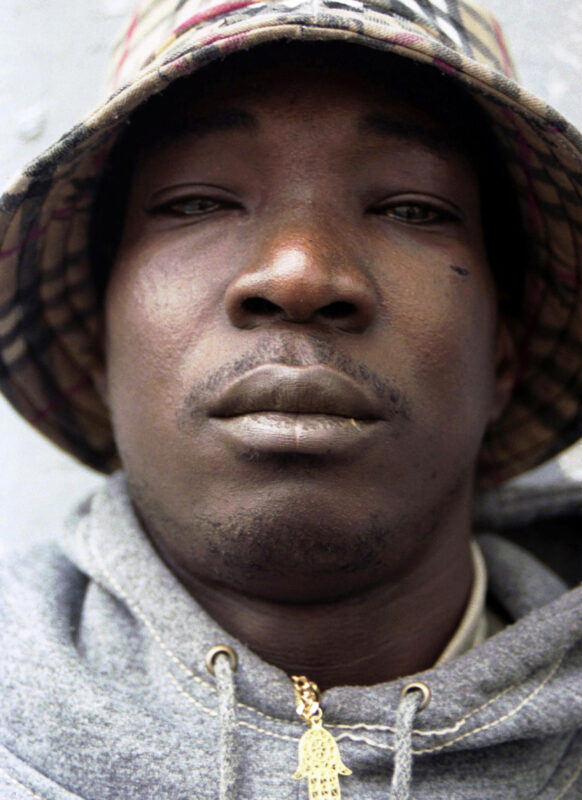

Research-led curatorial initiatives include multiple iterations of The Missing Chapter – Black Chronicles programmes, including most recently Black Chronicles IV (2018), The African Choir 1891 Re-Imagined (2016-18) and Black Chronicles: Photographic Portraits (2017) at the National Portrait Gallery, London. Independent curatorial and editorial projects include the collaborative Women’s Mobile Museum (2018, with Zanele Muholi and the Philadelphia Photo Arts Center) and Glyphs: Acts of Inscription (2013, with Ruti Talmor).

Mussai is a regular guest curator and former fellow at the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University; Research Associate at the Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre, University of Johannesburg; Associate Lecturer at University of the Arts London; and part-time PhD candidate in History of Art at University College London where she is completing her doctoral thesis on nineteenth century ‘raced’ portrait photography and contemporary curatorial care. She serves on various awards and steering committees, including Fast Forward: Women in Photography, and publishes and lectures internationally on photography, visual culture and curatorial activism. Her writing has appeared in artist monographs and publications such as Aperture or Nka, and her edited volumes include Lina Iris Viktor: Some Are Born To Endless Night — Dark Matter (2019/20), James Barnor: Ever Young (2015) and Aida Silvestri: Unsterile Clinic/Even This Will Pass (2017).

She is currently working on several forthcoming publications in development, and co-managing a new series of artist commissions entitled Care, Contagion, Community at Autograph.

What is it that attracts you to the exhibition form?

Exhibitions – whether staged inside institutions or as interventions in public realms; monographic, retrospective, thematic etc – appeal to me as locations of enquiry, as situational spaces of discourse, as sites of visual pleasure. I enjoy the collaborative nature of exhibitions, and myriad possibilities they offer… as sensory places for engagement, as experimental laboratories, as zones of reflection and contemplation. They enable us to show/do so many things simultaneously: to create openings where different exchanges can take place, encounters occur, imaginaries manifest, ideas evolve, dialogues emerge, positions take shape.

I think of the exhibition as both proposition, and provocation – as an invitation to enter a conversation – between the artworks on display, the architectures of the space, between artist and curator, between the past and the present, and importantly with and for those who visit, navigate, participate, and affect its modalities. On a practical level, I am attracted to the multiple dramaturgic dimensions the exhibition offers – discursive, textual, spatial and otherwise: the idea of an empty stage to play with, infused with colours, objects, texts – I like the idea of exhibitions as ‘visual essays’ where constellations of words and images, thoughts and objects, co-exist inside these temporary curatorial ecologies.

Exhibition-making for me is a creative, generative ‘doing’ activity – dialogic, and activist at its core… the desire is to create a visceral experience – yet one that is at once emotional, intellectual, political, personal, sensual – that is felt in the body and the mind, and hopefully, proves restorative and transformative for/to some… encourages different ways of seeing, thinking, and being – even if only temporary – and invites us to reflect and think critically about our core values, the changing worlds we live in, the historical conditions that have shaped us… and to imagine possible futures and different modes of futurity.

And crucially, as sites of evidence, exhibitions enable us to showcase the work of visionary – and often underrepresented – artists and foreground artistic voices still too often marginalised within the art “world”… to advocate for those forged into/from various registers of difference, working at the intersection of race, class, gender and sexuality – in my case especially female, and non-binary/queer artists of colour from the African diaspora who use their practice to raise awareness to socio-cultural thematics, including conceptual artists-activists such as Zanele Muholi, Lola Flash, Aida Silvestri, Phoebe Boswell or Lina Iris Viktor.

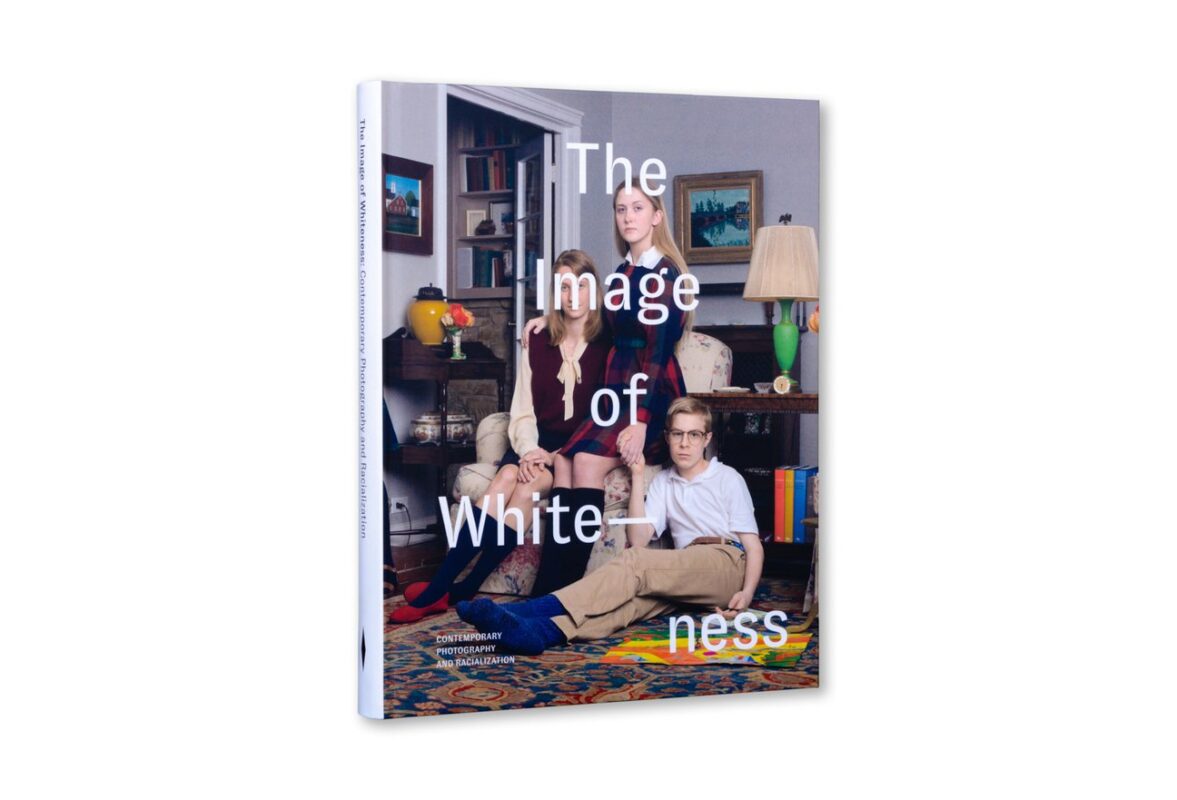

So, the exhibition can be a space of refuge, offering both critique and hope: I see the making of exhibitions, and curating as a praxis, as a form of resistance – and insistence – an opportunity to ‘practice refusal’: to stage a disruption of the traditional white cube space – and deluminate its metaphorical and literal whiteness. I am interested in the communion between art and activism – its disrupting power, if you will – and in the transformation and activation of space(s): painting gallery walls black, for instance, is a favourite curatorial gesture/pleasure … especially inside mainstream institutions!

What does it mean to be a curator in an age of image and information excess?

This depends entirely on what we understand by/as excess, and what kinds of images and information we feel exist in surplus? I would say, in response, that this is ultimately a question of perspective. What constitutes too much, and not enough? Too little or too many images of which kind – still too many afro-pessimist images yet still not enough afro-futurist images, for instance? Do we really see enough images of non-white people in positions of power or moments of leisure? Too many images of people of colour suffering, of black and brown and queer bodies under duress circulated without care? Do we have enough images and information to make us see the urgency of climate crises unfolding? What about indigenous image archives? Where is the excess when it comes to images by people from the majority world in global picture libraries?

For me, working as a curator in the decolonial mode means to continuously question both excess and lack in relation to images and their affective registers. It means to continuously look out for blind spots, and trace proverbial ‘black holes’ in existing image repertoires – searching for ‘missing’ images within information excess marked by notions power and privilege. We know that the photographic archive/history of photography – both past and present – is full of omissions, gaps and misrepresentations. What type of information and imagery continues to be buried? Who remains invisible, in this ‘age of image and information excess’? Who produces the critical context of these images? Who controls the flow of information and image?

In other words – as I contemplate your question, I am deeply immersed in ongoing research into Victorian image repertoires and the recovery of photographs of black figures in nineteenth century Britain – part of our critical curatorial labour to activate the archive as a radical locus for knowledge production and diasporic visibility. Until very recently, both information and images on this topic were scarce – with hundreds of images ‘lost’ in the archive for decades – remediated only now by the long-term curatorial research initiated by Autograph under the the Black Chronicles – The Missing Chapter rubric, a programme that began in 2013 and continues today with forthcoming publications in progress.

Thus the location and implication of image/information excess is a critical and complex question to answer – especially when viewed through the lens of cultural politics of race + representation. It is also one intimately linked to the notion of ‘whose eyes’ – who is producing, curating and excavating our image and information archives? Who is looking? Who is affecting – and affected by – these oftentimes raced, classed and gendered optics through which both excess is constituted and lack maintained, and wherein certain images remain fugitive?

What is the most invaluable skill required for a curator?

In many ways curators, one could argue, are perpetual/involuntary professional shape-shifters, so perhaps the only skill truly invaluable might be the ability to adapt and combine different competencies… although the capacity to develop additional tentacles to better multi-task and problem-solve would be really helpful, too!

Critical thinking, writing and organising skills are important in my view – the ability to think differently – and transnationally, sensitively, curiously, inclusively, patiently, collaboratively and dialogically – to think with rather than about – and to think diagonally as well as non-hierarchically: curators tend to fulfil different roles, often simultaneously, operating in several occupational zones comprised of fragments from a range of hyphenated ‘curatorial’ identities: fundraiser–salesperson–gallerist–organiser–registrar–researcher–archivist–commissioner–writer–critic–editor–publisher–lecturer–educator–strategist–activist–educator–translator–designer, etc. A lot of the time we are administrators and project managers… at other times, some sort of curatorial agent-obstetrician – tasked with the birthing of partnerships, representation of artists and delivery of projects.

Since a majority of curatorial efforts, especially large-scale exhibitions, are joint operations with many collaborators and co-conspirators, being able to work collaboratively with people is key – the ability to connect, communicate and build caring relationships with others, especially with artists, first and foremost – but also with the many other stakeholders involved: colleagues, gallerists, designers, printers, framers, installers, technicians – as well funders, collectors, patrons, etc – and of course with audiences, for whom the work is staged.

What was your route into curating?

I have been fortunate to develop my curatorial practice within the trajectory of a unique, flexible, multifaceted small arts organisation with a strong mission – advocating for photography, film and lens-based media that addresses cultural politics of rights, race, and representation – and with the support of committed colleagues with enlightened curatorial visions.

I joined Autograph (led by director Mark Sealy who is also a very accomplished curator and writer) almost two decades ago, when I was in my early twenties, and an undergraduate student studying photography at the University of the Arts London. This long-term, sustained organisational/institutional affiliation has been deeply rewarding… I initially worked across different areas – including education, print sales and artist liaison, with job titles ranging from researcher to archive project manager and eventually curator. I also spent my formative curatorial years at Autograph working inside our permanent collection of photography: collections and archives are wonderful – and often underrated – sites for any fledgling curator to acquire invaluable skills and knowledges; absolutely crucial in my view as spaces to help formulate thoughts, practice curiosity, and explore ideas for future exhibitions, or publications. My first big curatorial project, a retrospective of James Barnor, and later exhibitions such as Miss Black & Beautiful – were born out of early curatorial archive and collection work.

And, because Autograph operates internationally through an agency model based on partnerships with peer organisations, I’ve learned a lot from working in a guest curatorial capacity within different spaces and institutional structures, both ideologically and geographically. As gallery, publisher, and commissioning body, we have over the years placed great emphasis on developing a space of making, and working closely with artists has been, and continues to be, the greatest privilege. Much of my curatorial work is developed through in-depth dialogue and exchange with artists, often over long periods of time. We have just launched an exciting new series of artist commissions at Autograph entitled ‘care – contagion – communion: self & other’, in response to the wider context and implications of Covid-19.

My route into curating is also a story of migration in reverse: my educational background is both academic and practice-based, having trained as an artist for five years, after studying combined humanities at the University of Vienna – history of art, film studies, theatre science, and philosophy. Curating offered a way to bring these various areas of interest together, and engage in visual politics as creative practitioner, scholar and facilitator, while also developing my writing and teaching practice.

What is the most memorable exhibition that you’ve visited?

The most memorable exhibition? Perhaps Alfredo Jaar’s The Sound of Silence, which I first saw at Fabrica as part of the Brighton Photo Biennial in 2006, an ingenious installation which features only one single photographic image visible for a matter of seconds… the critical questions the exhibition posed – about the limits of representation, the failure of photography, the psycho-social and political implications of the documentary genre, the precarity of human rights and our responsibility as image makers, image takers and image consumers – have stayed with me palpably ever since.

I often return to the Walther Collection’s inaugural exhibition Events of the Self: Portraiture and Social Identity curated by the late Okwui Enwezor whose pioneering curatorial vision placed the work of celebrated African and German portrait photographers – such as August Sander and Seydou Keïta – in close dialogue with one another. It opened up a discursive dialogue across different geographies, modernities and temporalities, while inadvertently questioning how canons are made/maintained, and photographic traditions constituted as separate rather than parallel and intimately entwined histories.

A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965 – 2016, Adrian Piper’s retrospective at MoMA was infinitely memorable: an incredibly rich unpacking of fifty years of conceptual art practice, and a truly generous curatorial offering. A beautiful gift of a show… even reproductions of Piper’s seminal Calling Cards were freely available to visitors as printed tools to confront recurrent acts of racism and sexism many of us experience regularly: as relevant now as they were when Piper first produced them in the 1980s and 90s.

An exhibition I often wish I had seen is Like A Virgin organised by the late Bisi Silva at her Center for Contemporary Art in Lagos, Nigeria in 2007. Bisi was a wonderful curator of contemporary African art and photography – and this was a courageous and bold exhibition to curate about African women’s radical sexualities in a place that does not openly welcome such dialogues (LGTBQIA+ politics on the African continent are still deeply precarious and living is dangerous for those who advocate for freedom of expression and equality). I have spent so much time talking, thinking and imagining this show, that it somehow feels ‘memorable’ although I haven’t actually seen it.

What constitutes curatorial responsibility in the context within which you work?

To me, curatorial responsibility is intimately linked to the notion of curatorial care – curating as a praxis of care. Etymologically, curate derives from the Latin cura/curare, meaning ‘care/to care’. In the context of my own curatorial praxis/practice – and in the wider context within which we work collectively at Autograph – curating is tied not only to ideas around the ethics of care, but also the notion of repair: a remedial doing and undoing, a continuous addressing and redressing, a suturing of broken archaeologies, an offering of an alternate (curatorial) ‘otherwise’.

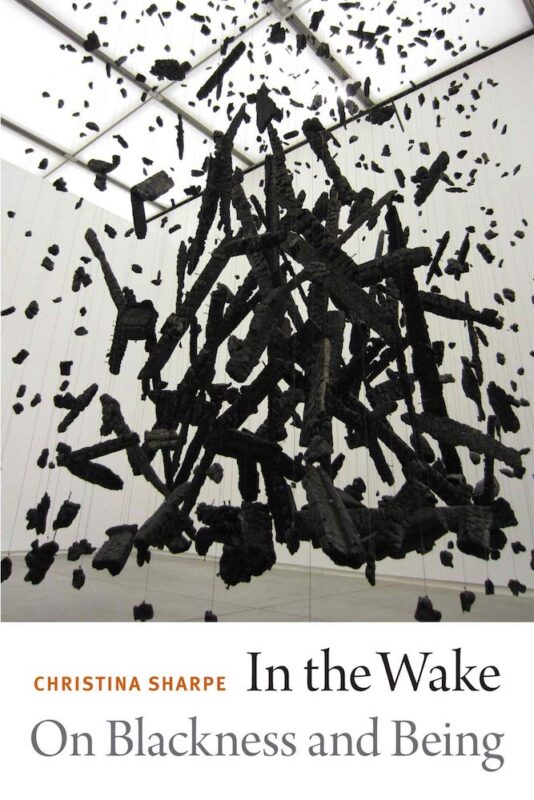

I think of this affective cultural labour as remedial curatorial care work – a feminist, activist, decolonial kind of antidote and embrace… which also reflects the critical thinking of black feminist scholarship (from Audre Lorde to Hortense Spillers to Saidiya Hartman, and others) and, in particular, the sentiment the brilliant scholar Christina Sharpe posits as critical wake work in her beautiful mediation In the Wake, On Blackness and Being. I am currently developing these ideas further, in my ongoing writing/thinking for a series of essays and chapters in progress – hence reflecting deeply on the question of curatorial responsibility, and how to make a difference.

Within this ecology of curatorial care, our responsibility is first and foremost to the artists – and the work entrusted to us, and then, if appropriate, to the archive, as well as to our audiences: to operate ethically with integrity, sensitivity, and respect, while opening doors, and – where possible – break down barriers of access. As both praxis, and process, this remedial curatorial care work I describe entails a deep commitment to diversity, and within that our curatorial responsibility – or response-ability, to borrow Toni Morrison’s phrase – is to continuously support new and different voices – to act and activate our power(s) to create inclusive spaces for solidarity and multiple occupancies: it means a long-term promise to work towards cultural and structural change and social justice – towards a counter hegemonic ‘otherwise’, if you will.

Ultimately, curatorial responsibility for me constitutes a continual – not intermittent –commitment to tackle notions of heteropatriarchy and euro-centrism, and other deeply engrained regimes that must be undone: all those structural inequalities, empty policies and toxic ideologies that so stubbornly prevail within institutions and societies at large – from systemic racism, sexism, classism, ableism, to queer/trans/lesbo and homophobia, and countless others. How do we best – collectively and individually – challenge such sentiments and unfix oppressive, established narratives? The key I believe is to practise the doing and acting inherent within the notion of response-ability, to keep speaking up against discriminatory, exclusionary practices – both actions or non-actions – and doing our part in helping to accelerate this slow process of diversification, cultural reform and gradual change within institutions, and beyond – taxing and difficult as this affective labour is at times, and of course often disproportionally burdened onto black and brown professionals in the arts (and academia, too)… efforts imbued with a renewed sense of urgency in the wake of Covid-19, the recent killings of people of colour in the US and elsewhere, the ongoing protests and monument ‘wars’, the decolonising and dismantling campaigns, and of course, crucially, the Black Lives Matter movement.

It also entails a sense of critical self-reflexivity – including an awareness and regular assessment of our own privilege(s) and biases, as well as our agency. Are we doing the work? Are we doing enough? Who do we represent? Are we empowering others? Might we be complicit in upholding certain existing power structures? Does our care include care for the climate, care for others, care for the self – e.g Do I really need to take this flight, or speak on this panel? Might there be someone local who could speak to the topic instead, someone less privileged or less salaried perhaps? May I rest?

What is the one myth that you would like to dispel around being a curator?

There is value in myths, and on a tired day I’d be inclined to say just allow them to grow … The term ‘curator’ has become both terribly charged, and strangely desirable lately – so many other ‘titles’ we could use instead: cultural facilitator, exhibitions organiser, or creative producer… It would be nice to dispel the inherent ideas of authority, of curators as gatekeeper, and undo the ‘top down’ hierarchies often implied… Curating, in my experience, is rarely a solitary form of creativity or activity that warrants recognition through individual/single authorship – curating is relational, situational, and inherently collaborative. I think we should speak more about how curatorial pleasure – and curatorial resilience – is often forged in those moments of intimate, and sustained, dialogue – especially with artists, but also peers, colleagues, collaborators, and audiences. It’s all about working together, mutual support and learning from one another.

What advice would you give to aspiring curators?

Be brave, and courageous. Care, and dare. Make trouble… Take risks. Nurture what the brilliant speculative fiction writer Octavia E. Butler coined as ‘positive obsession’: decide what you want, aim carefully, go for it and keep going.

Research meticulously. Build your curatorial toolbox. Gain as much practical experience working on different projects as possible. Keep learning and un-learning… Think global, and decolonial. Don’t be afraid to seek counsel from others, be open to the possibility of failure, and course-correction… build bridges, and resilience. Challenge existing power structures. Be reflexive: why am I doing this? What’s at stake? What contribution am I making to the field? Does what I propose shift or enrich the conversation? Is it urgent? Is it relevant? Who needs it? Why now – is this the right time? Who is it for? Is the audience ready for this?

And don’t forget to think about the ethics [of curating], be conscious of your own position/positionality. Always look after and protect your artists… and look for allies. Collaborate. Learn from others. Find your tribe. Reach out. Share. Be generous. And enjoy….♦

Further interviews in the Curator Conversations series can be read here.

Click here to order your copy of the book

—

Curator Conversations is part of a collaborative set of activities on photography curation and scholarship initiated by Tim Clark (1000 Words and The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University), Christopher Stewart (London College of Communication, University of the Arts London) and Esther Teichmann (Royal College of Art) that has included the symposium, Encounters: Photography and Curation, in 2018 and a ten week course, Photography and Curation, hosted by The Photographers’ Gallery, London in 2018-19.

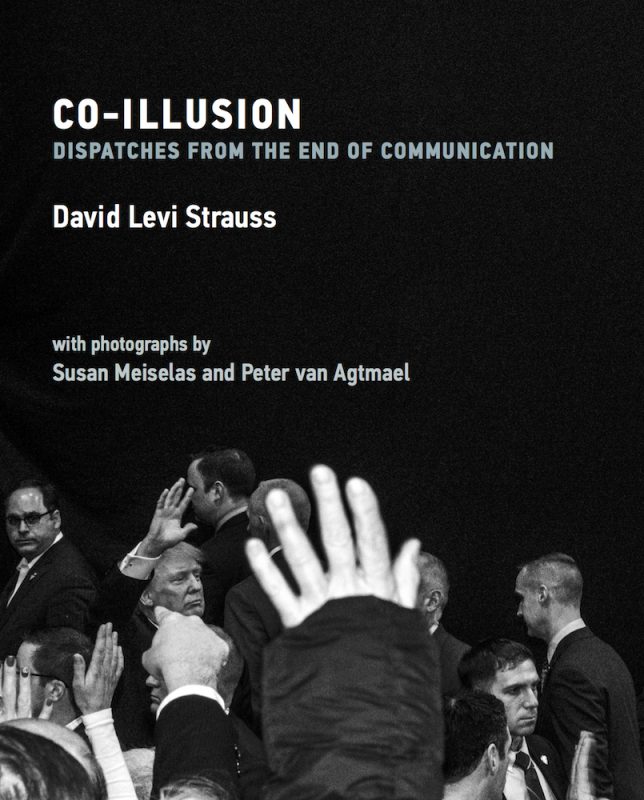

Images:

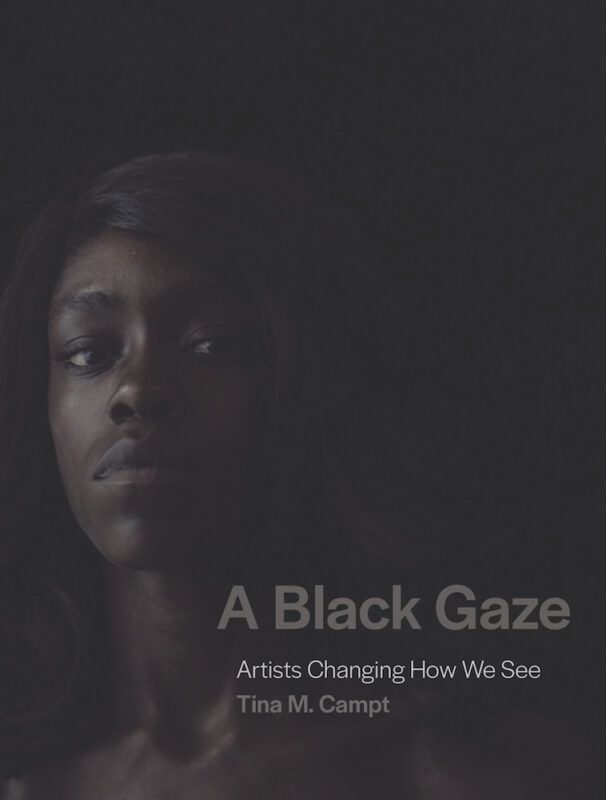

1-Renée Mussai in the exhibition Lina Iris Viktor: Some Are Born To Endless Night — Dark Matter, Autograph London, 2020.

2-Installation view of Lina Iris Viktor: Some Are Born To Endless Night — Dark Matter, Autograph London, 2020. © Ben Reeves.

3-Installation view of Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, Autograph London, 2017. © Zoe Maxwell.

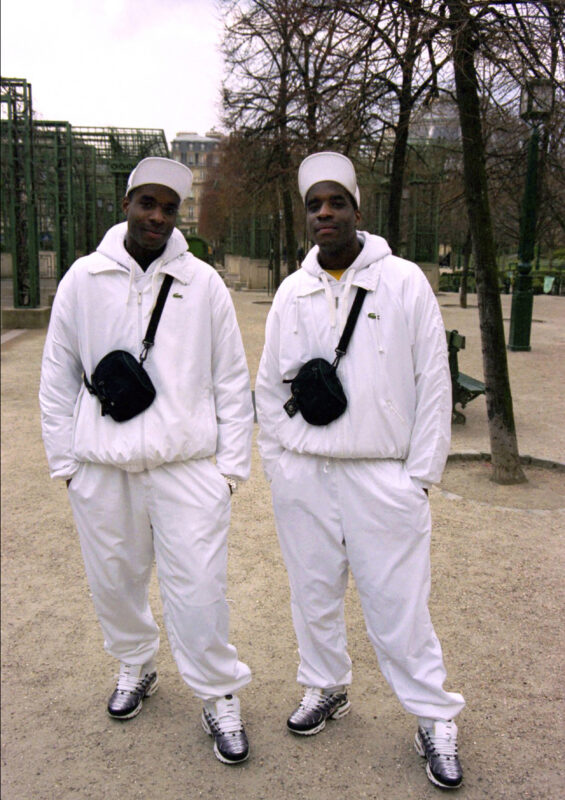

4-Installation view of Black Chronicles II, Autograph London, 2014. © Keri-Luke Campell.