Alexandra Catiere

Here, Beyond the Mists

Essay by Natasha Christia

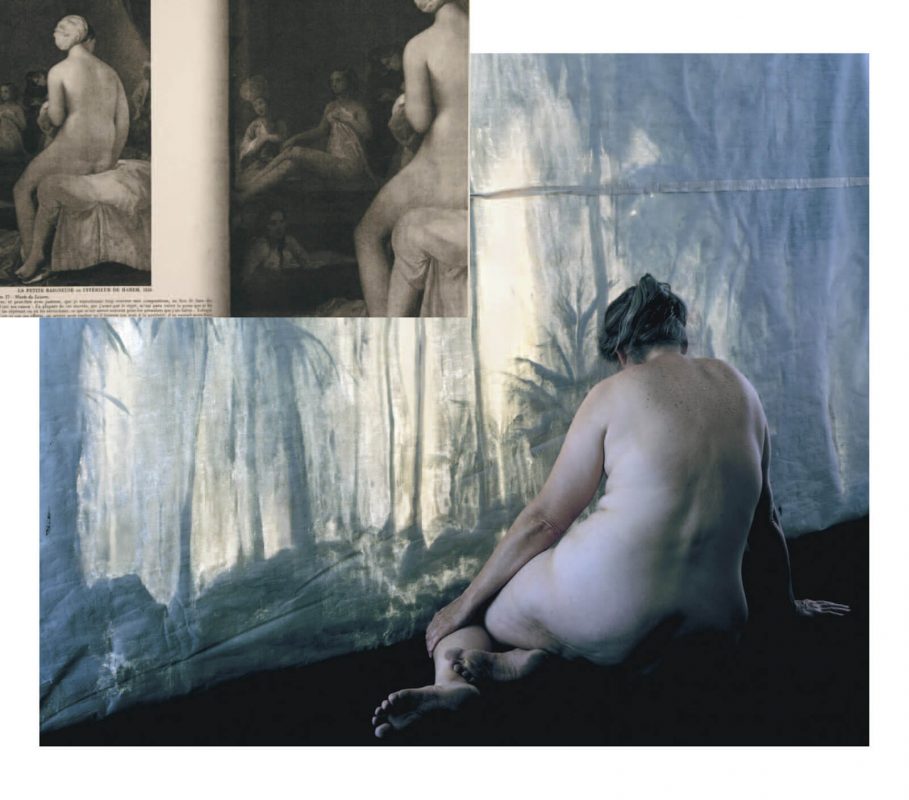

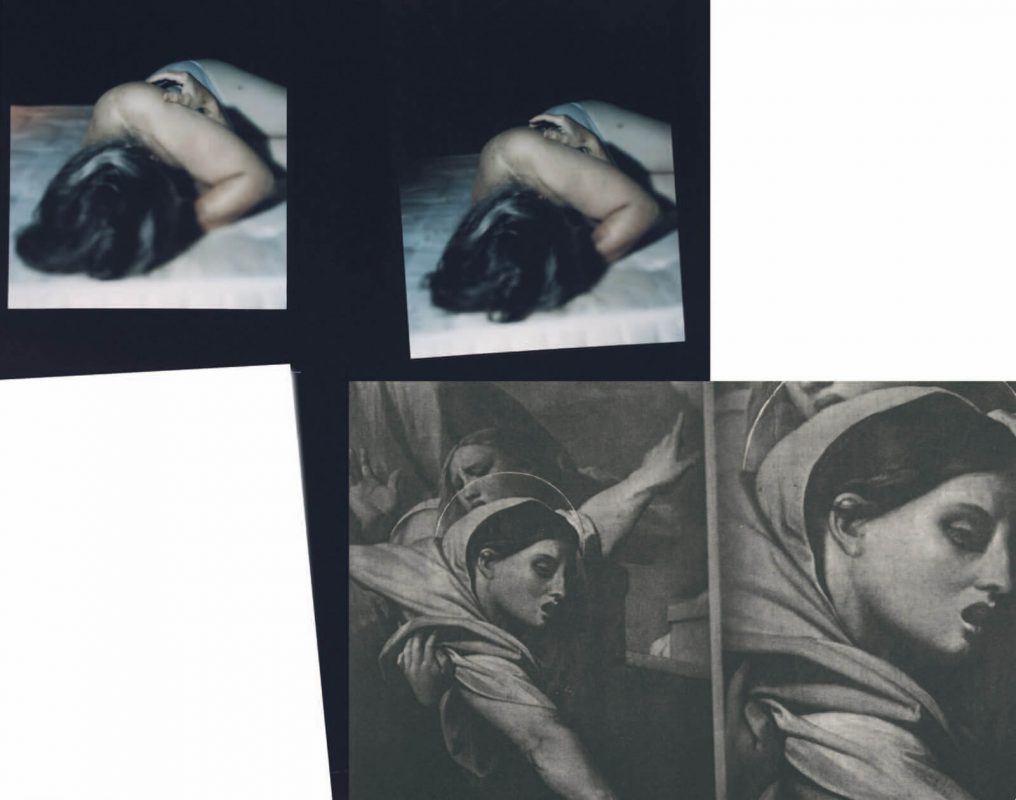

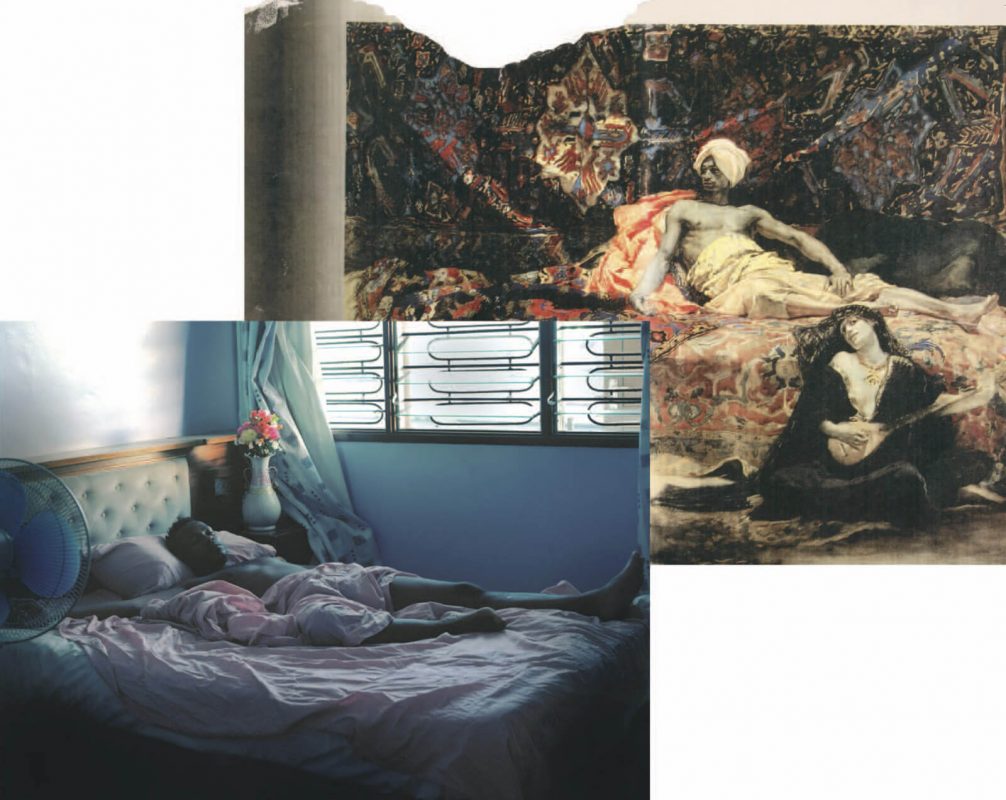

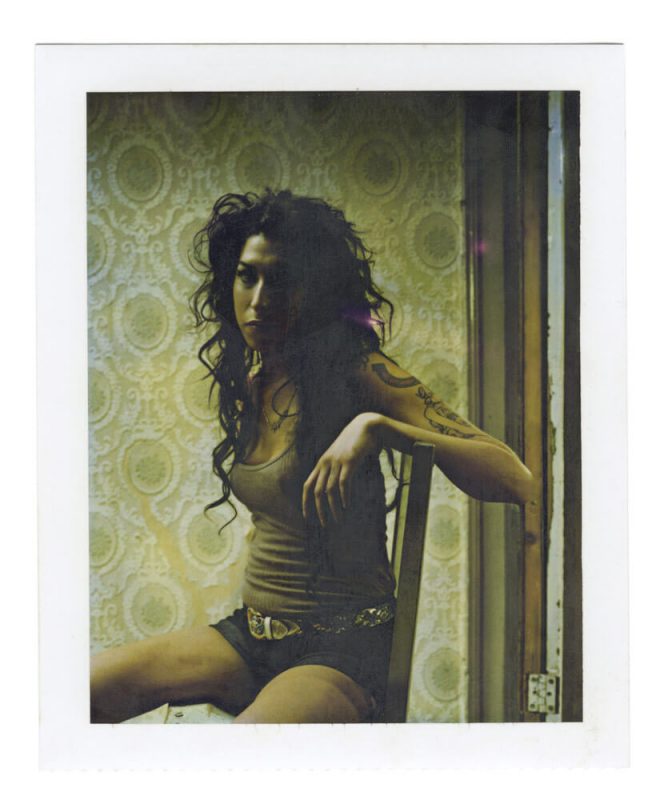

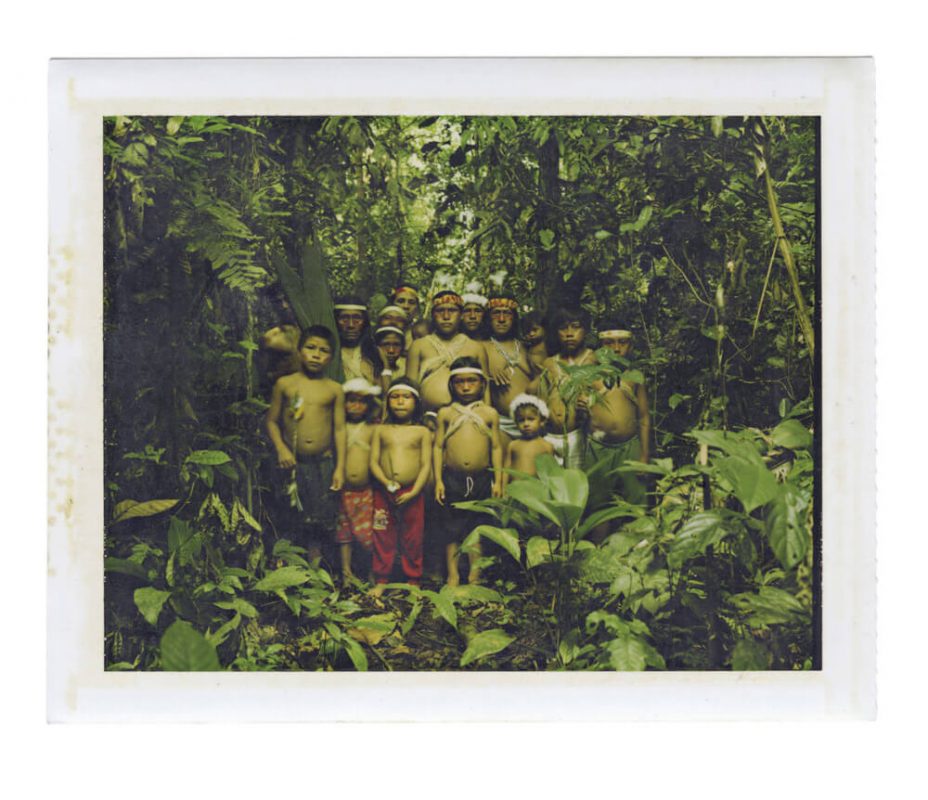

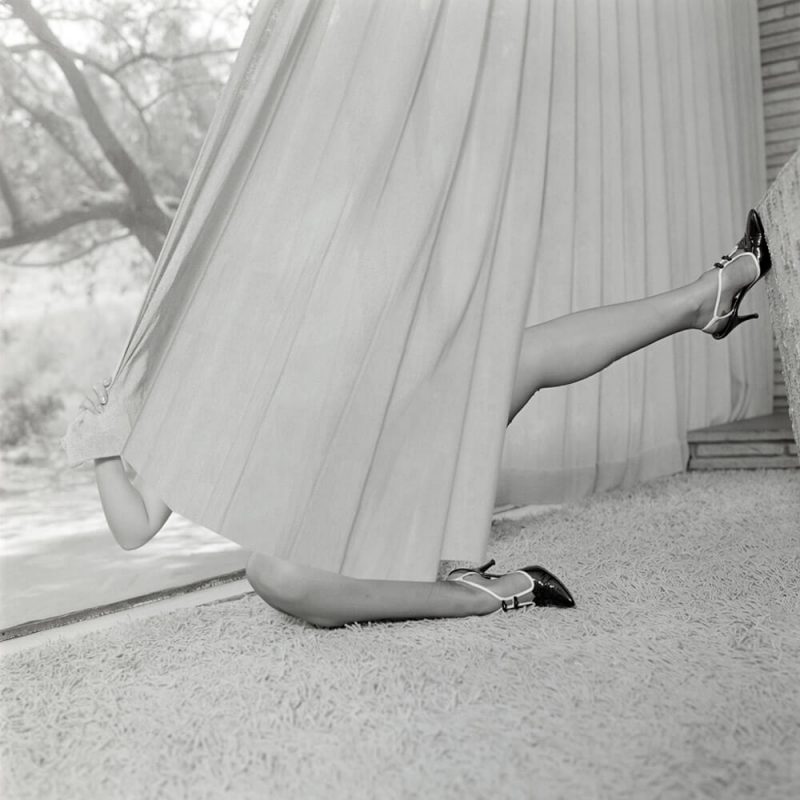

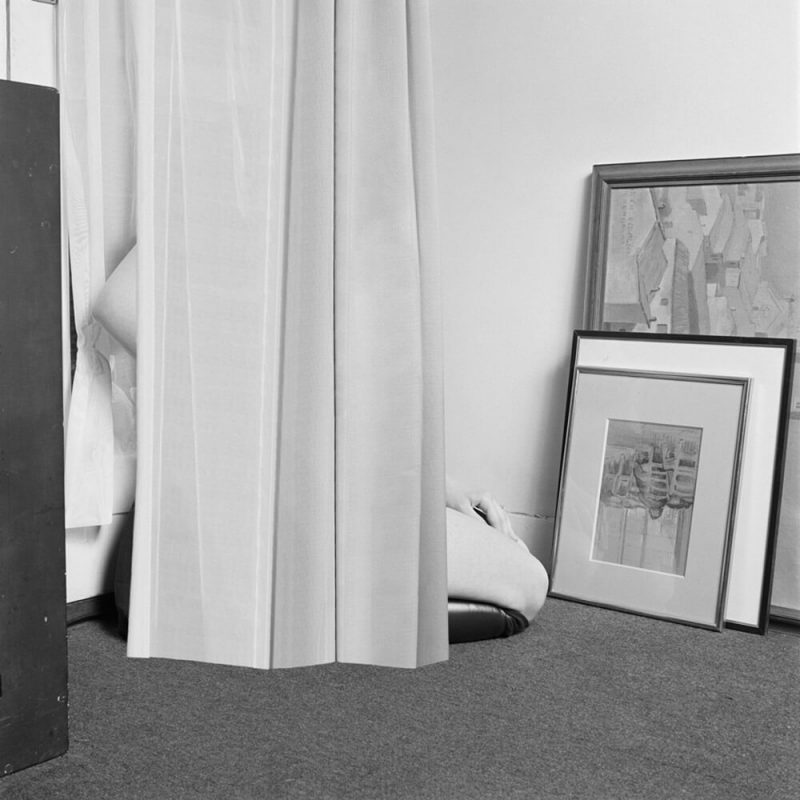

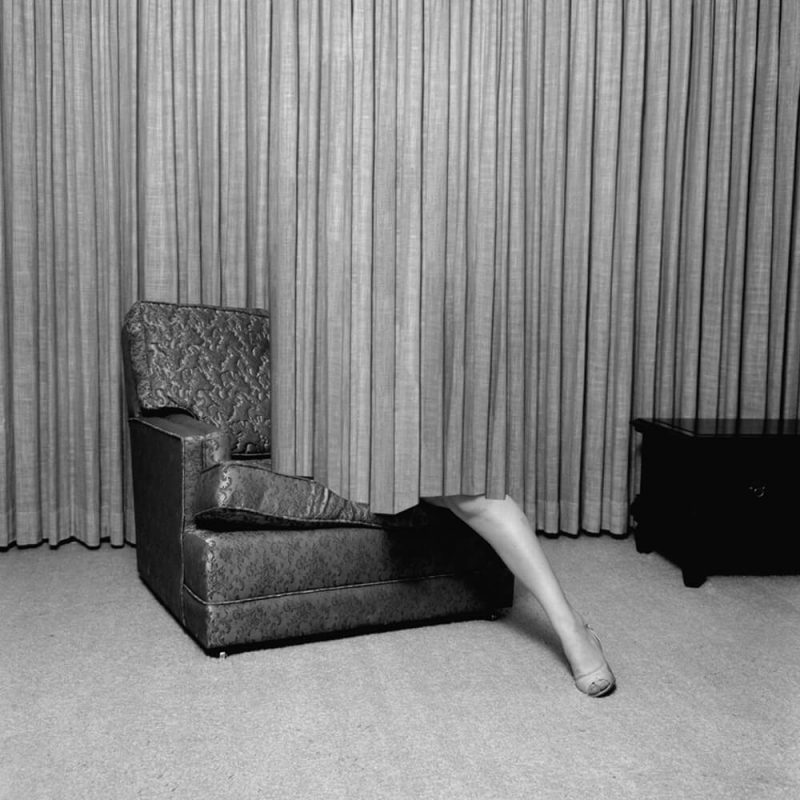

In the photography of Alexandra Catiere there is a subtle light burning, something akin to a frail but persistent memory that cannot be fully restored. Through these pictures, shot mainly in Chalon-sur-Saône, France, we encounter the remains of an agonising perception – unfinished and rapidly consumed. Something intrigues us to return to her work again and again, relentlessly trying to recover now what it felt like before, and yet also strangely as if felt for the first time. Like a speech running after the lights are dimmed, Catiere’s photographs trigger within us a sense of something irremediably lost but still somehow present. An abrupt flash-bolt, they mark a primal moment of photographic genesis, in which everything surges forth from the depths.

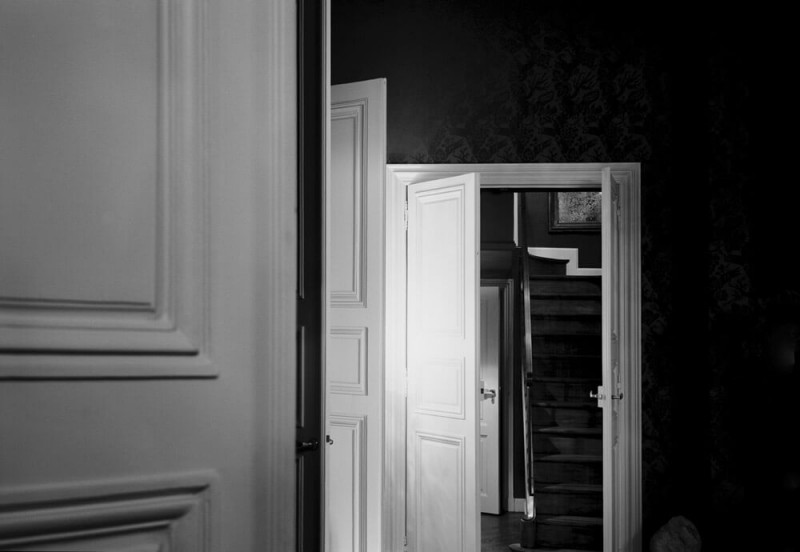

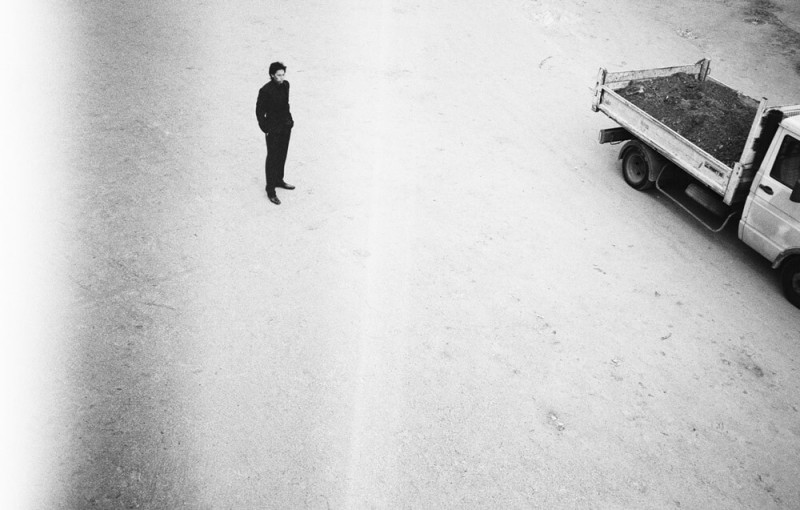

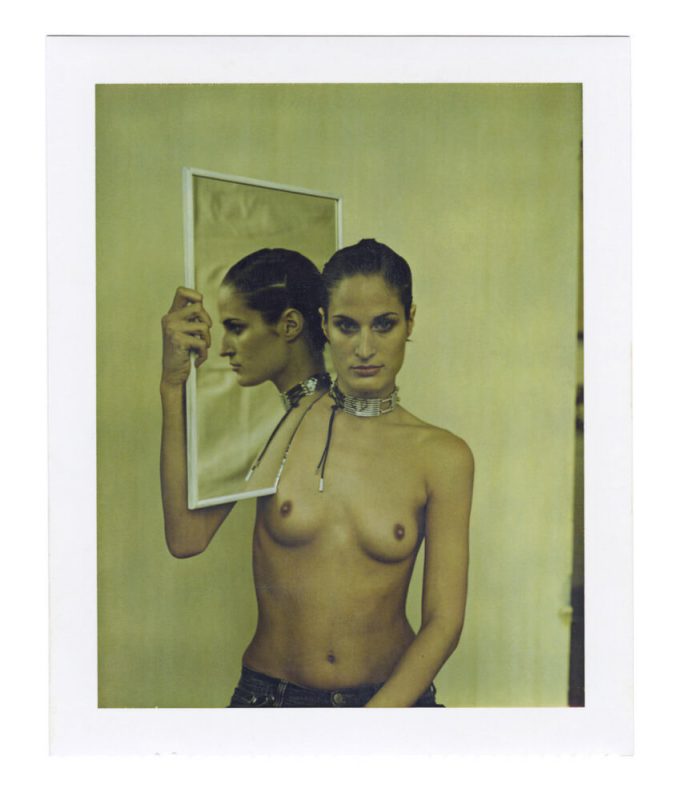

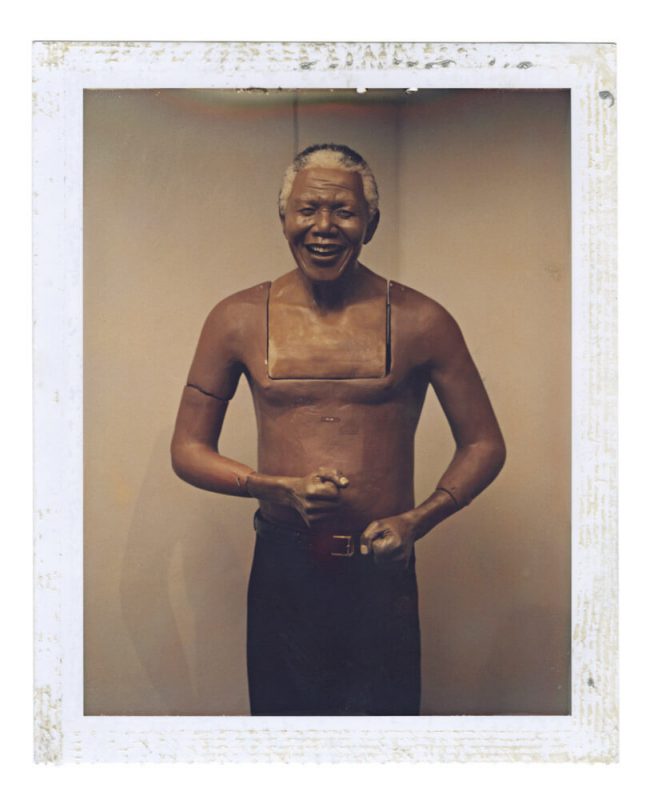

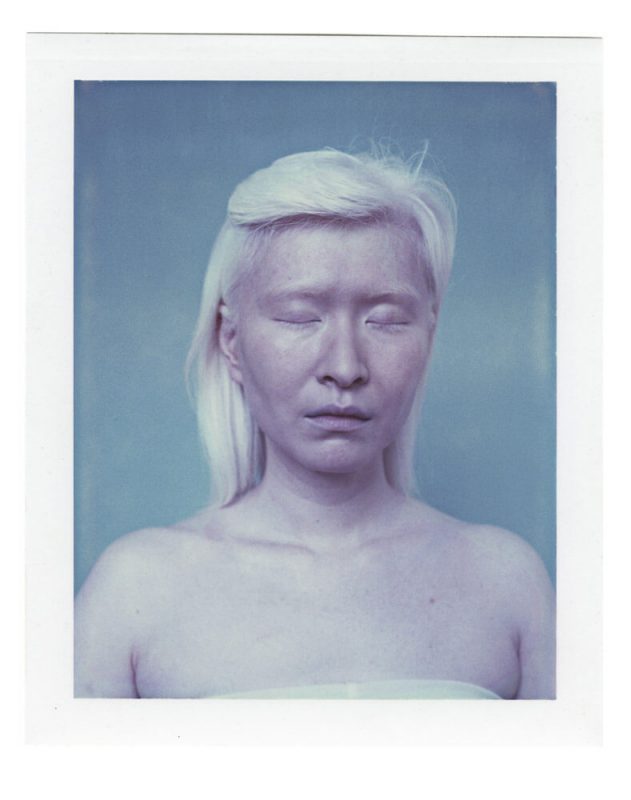

Catiere’s photographs carry the audacious transparency of a glance that announces its own partiality. Far from being instantaneous shots capturing merely the mundane aura of a city and its people, they are loaded with a timeless, dignifying gentleness that successfully bridges the space between wonder and understanding. In the image that introduces her only book to date, a truck abandons the scene, rendering as its sole protagonist a slender male figure. Ethereal and almost reduced to a black spot, the man counterbalances the emptiness of the composition while reinforcing, in his staunch immobility, the impression that the meaning infused in the picture – essentially metaphysical at heart – is in fact encountered elsewhere, outside the frame.

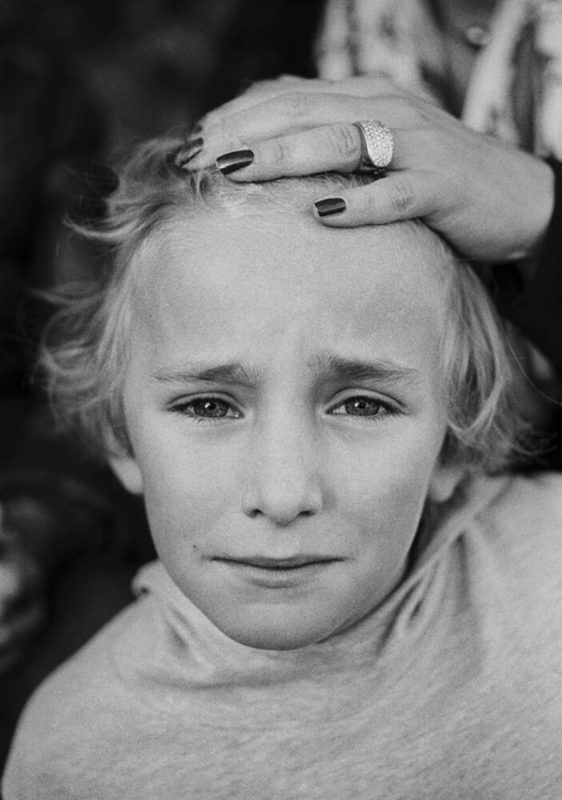

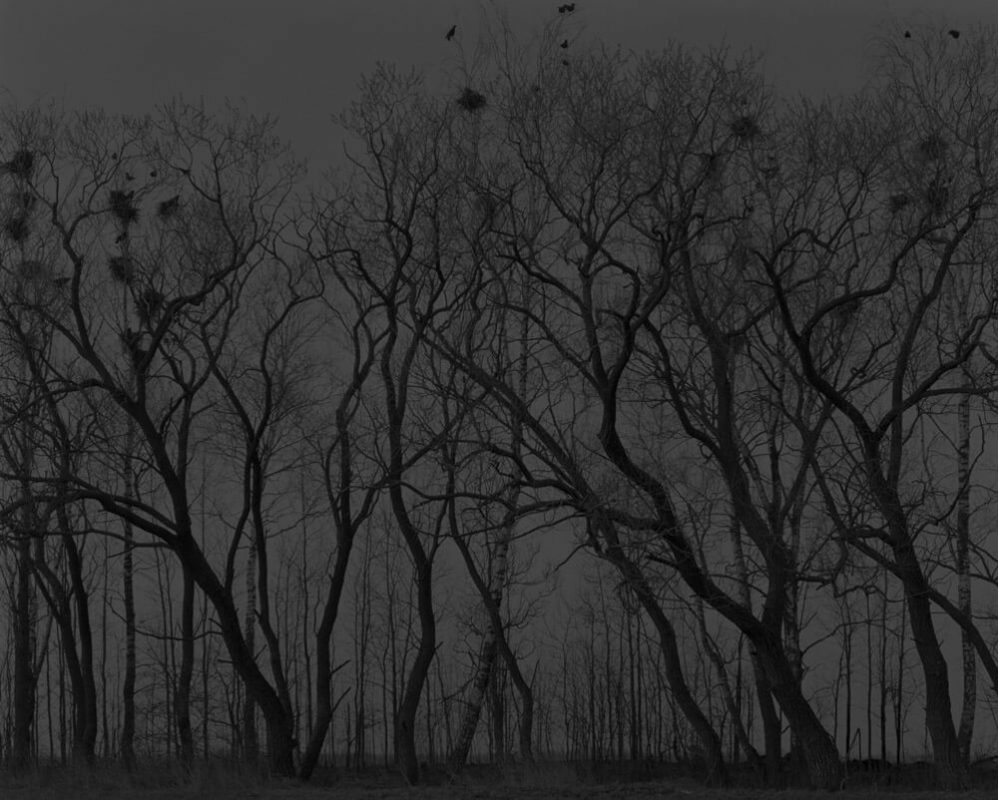

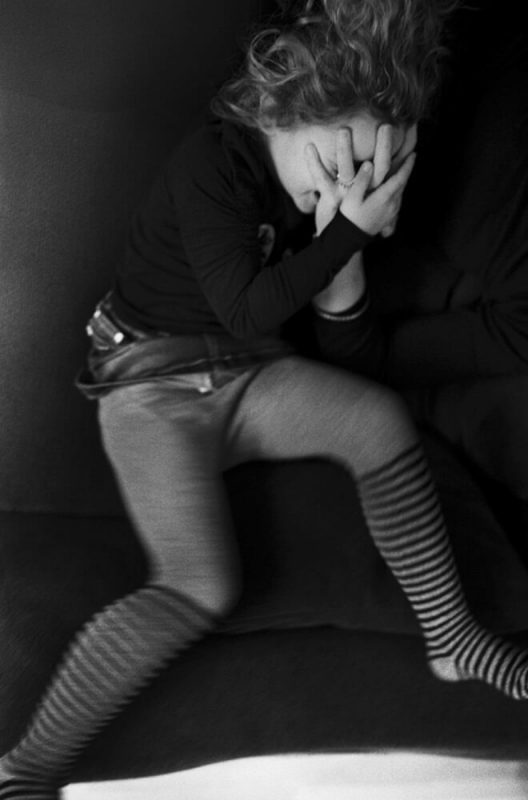

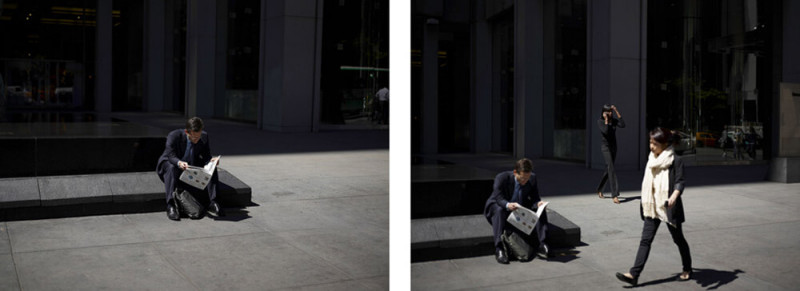

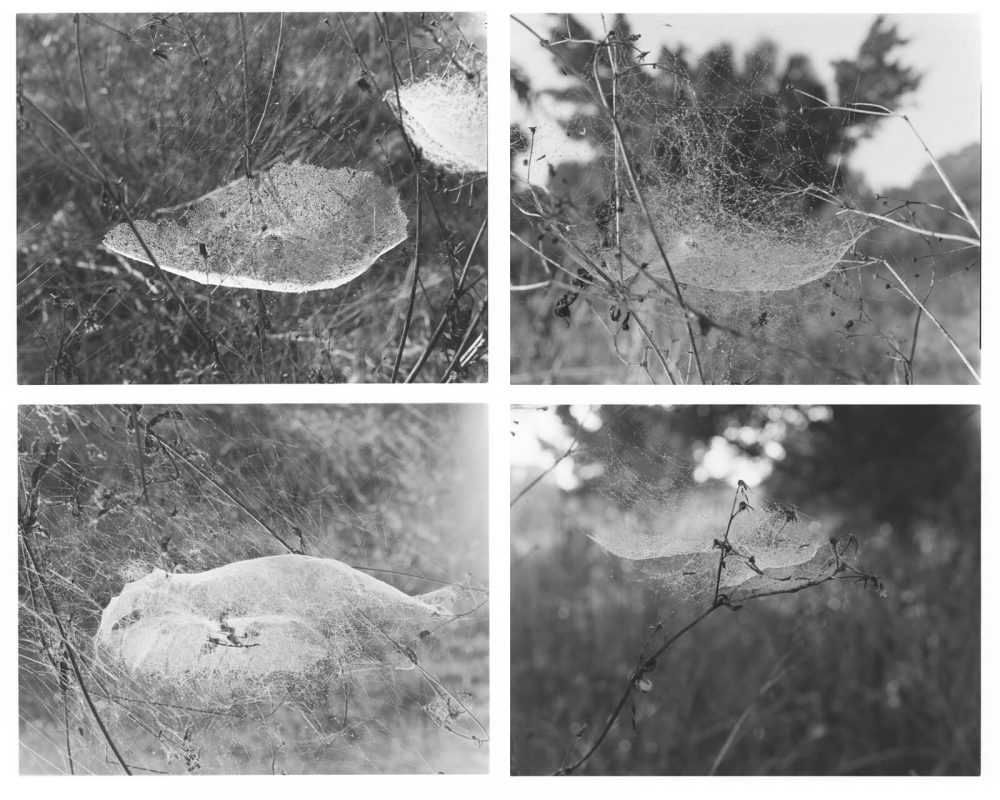

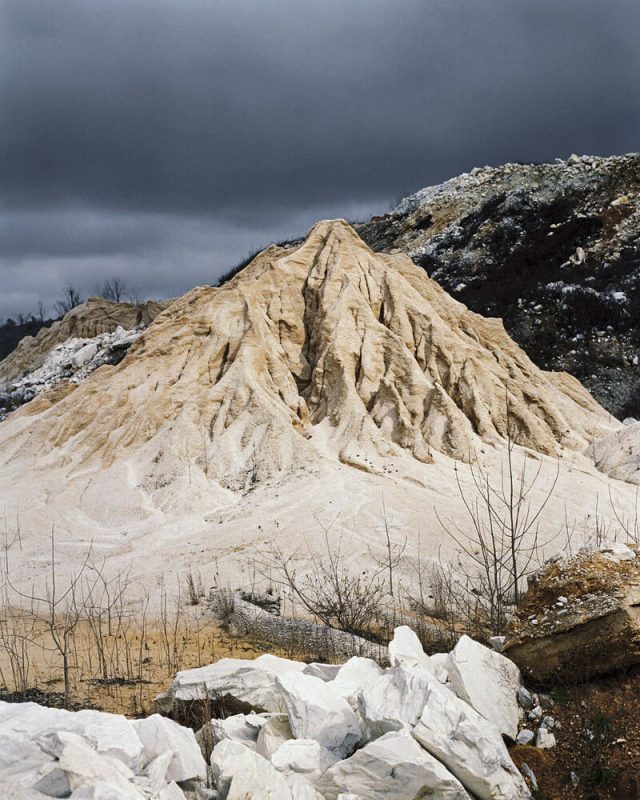

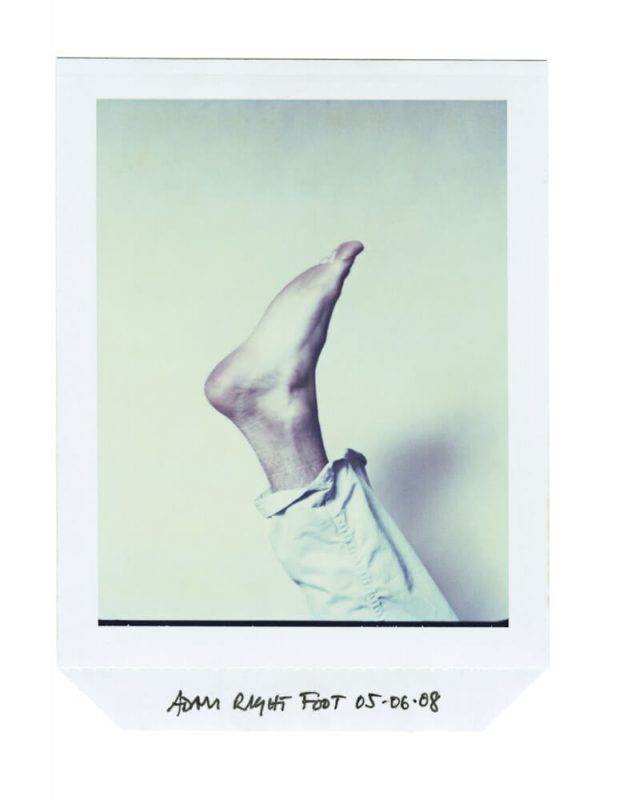

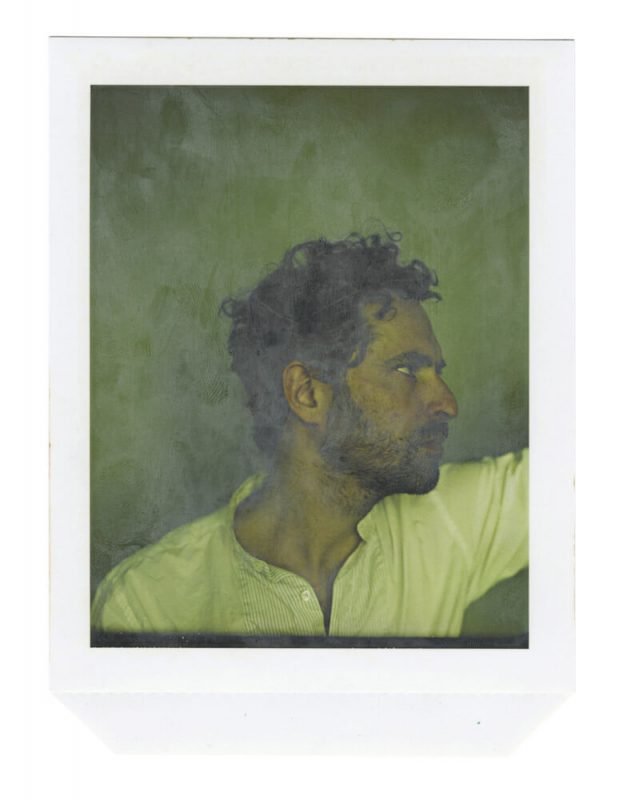

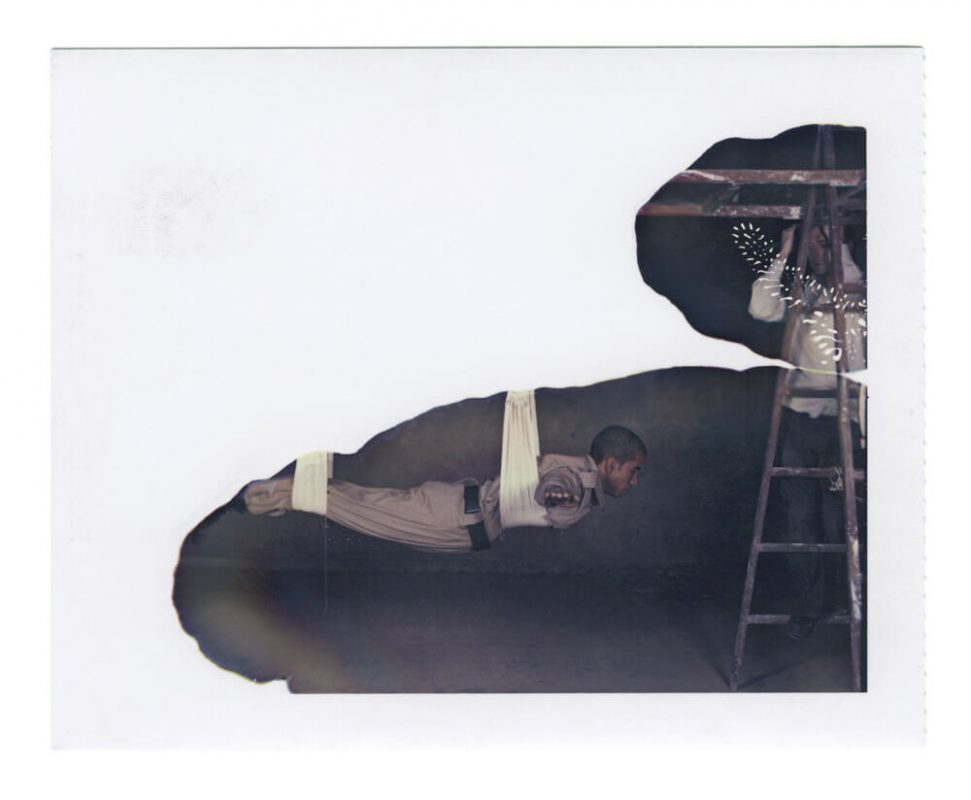

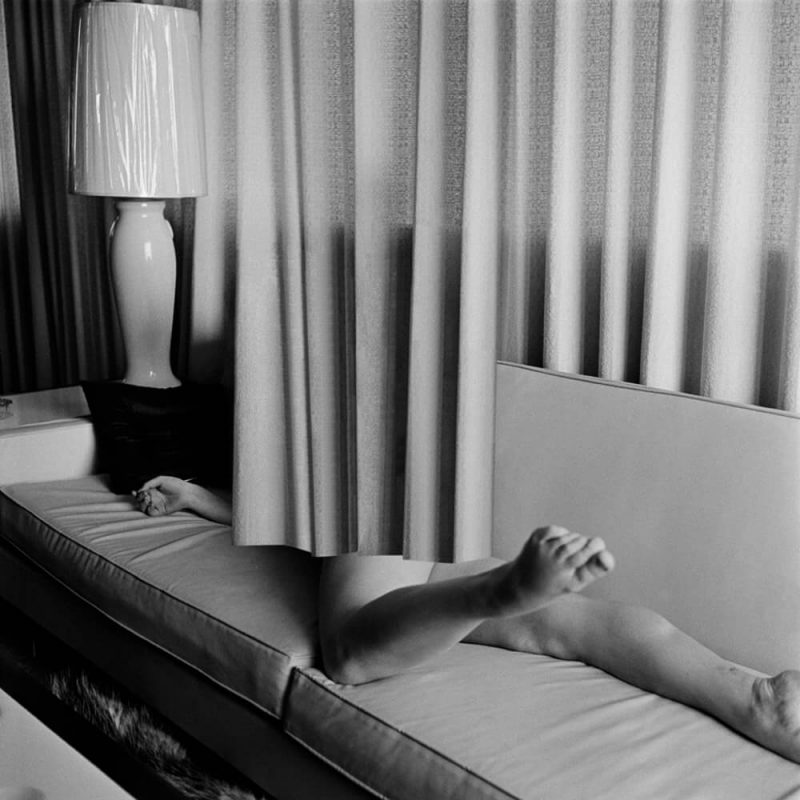

By the same token, doors and windows are frequently left half-open in Catiere’s photographs. There is always a way-out drawn by a photogenic light, a vanishing point that marks the path to a spiritual after-world beyond apparitions. In a good many portraits, the subjects appear as if they are on the verge of turning into somebody else. Or moreover their awkward poses suggest the possibility of an inner transformation. In the scenes of natural surroundings, the light mixes with the particles of the atmosphere, diluted amid the falling snowflakes that draw a profile of trees, humans and cityscapes. It is precisely this very moment, when the picture seems completely devoid of content, when its surface becomes an indefinable blank surface, that intrigues Catiere. Paradoxically, this moment of indecisiveness bestows upon us a reminiscence, only to take it away afterwards. It offers us the past as a coherent and plausible whole, but then dissolves it abruptly in the midst of the image, consumes it like a flame, leaving it incomplete, vague, mute.

The famous fog that lies like a blanket over the Saône river couldn’t be a better backdrop for the dreamful but contained imagery of Alexandra Catiere. Here, Beyond the Mists, the title chosen for the work, serves as an apt statement of purpose. Far from being mirrors of the world, her images are sparkles, fugitive apparitions. They are blank reflections of missing idols – of what we long for from the past but are unable to recover in the present; of something that, in its painstaking departure and absence, becomes properly ours. Loss is not the question here, nor is there space for drama or free melancholy. It is rather all about a sort of decaying vital information we carry in our genes and about what we can make of it.

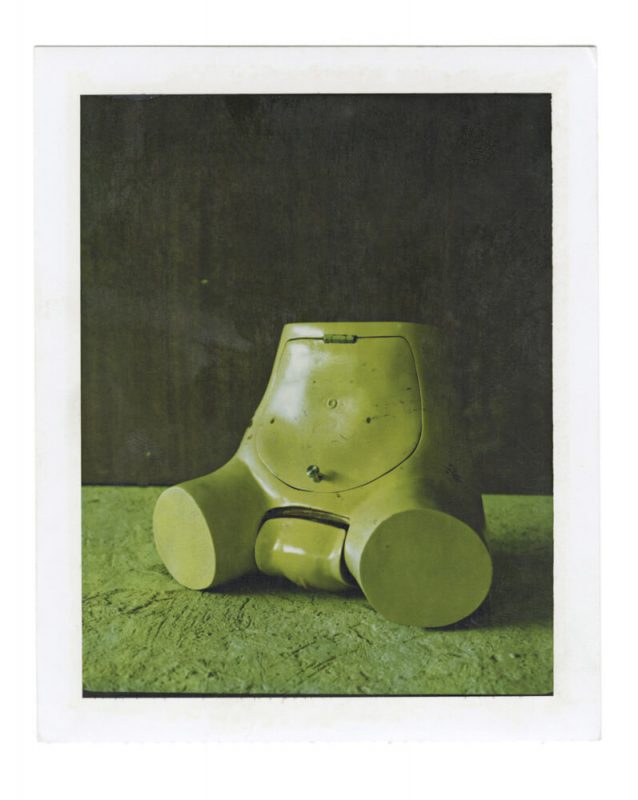

Light burns everything in these pictures. Light as evoked in the darkrooms of the first pioneers, light as the mystic force of the first heliographic experiments and their alchemical processes; glass negatives, plates and contact sheets. Even so, this young artist does not stick to the rules for her prints do not seek perfection. On the contrary, as if by a series of deliberate accidents, they push the limits in terms of contrasts, tonality and nuances, fostering a manner of expression that is distinctly contemporary.

While informed by the subtle and intimate lexicon of black and white imagery, her pictures conjure a space devoid of solid statement. Eschewing creative ties and affinities with her generation, her works go further to integrating the old and the new into an unvarnished map of personal sensibility. Catiere approaches her subjects, but also maintains an honest distance from them. The encounter between the photographer and the world around her is an ephemeral celebration steeped in empathy and honest exchange.

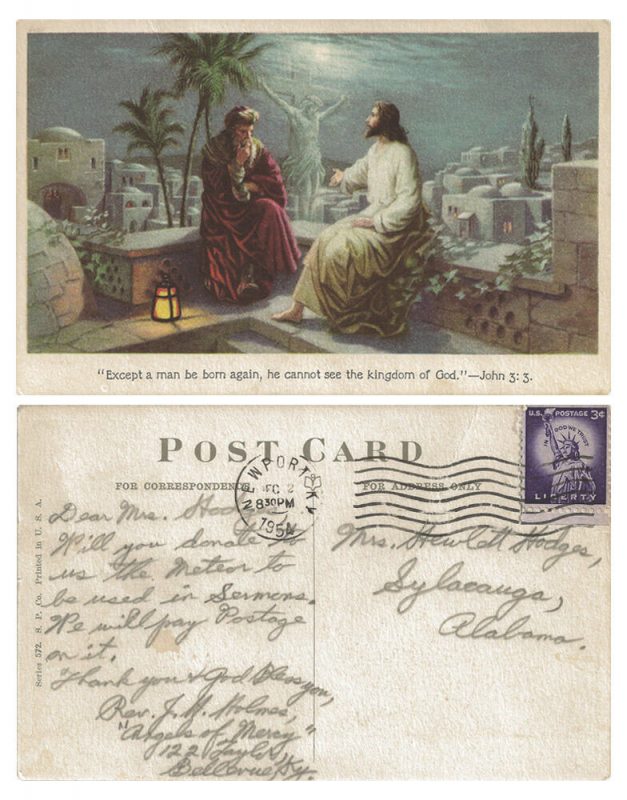

As a result, Catiere recollects, through her imagery, diverse emotions and moods, constantly evoking the circles of life, birth, childhood and ageing. The way she chooses to conclude her book – from Burgundy, France she goes back referencing her hometown Minsk, Belarus – reinforces this feeling of integration to the chain of an ever-changing historical reality. On the last page her book we encounter a tiny image that shows the statue of Nicéphore Niépce at a distance. Lost in the mist, could this represent a last homage to one of the fathers of photography ahead of a future that will be distinct photographically? Or is it, perhaps, the tangible record of a reminiscence diluting in the passage of time?

By turns gentle and haunting, Catiere’s photography raises awareness of the fact that memories do decay and that they lose their original shape and coherence. All that is left is to look at and discover the beauty beyond the mists – a beauty, proper to the living, pure and immaculate at heart, that will stand over the patina of time. ♦

Born in 1978 in Minsk, Belarus, Alexandra Cartiere initially began experimenting with photography at Minsk State Linguistic university. As encouraged by her mentor Youi Kuper, Cartiere moved to New York in 2003 to complete a certificate programme at the International Centre of Photography. She then worked as an assistant to internationally renowned photographer Irving Penn.

In 2005, Cartiere was listed as one of the twenty most promising emerging photographers in New York, and as a result participated in the Art & Commerce Festival, a travelling exhibition that began its tour in D.U.M.B.O, NYC. Since then, Cartiere has been named as an emerging star of International Photography in American Photo magazine, 2005, and exhibited at photography festivals in France, Japan, Italy and Spain. In 2006 she received a Silver Camera award from the Moscow House of Photography.

In 2009, Pobeda Gallery, Moscow, presented the work of Cartiere at Paris Photo and went on to showcase her new series at VOLTA6 in Basel in 2010. Cartiere was the artist chosen for the first BMW residency, a liaison established between BMW Art & Culture and the Museum Nicéphore Niépce in France. The work produced here, with the support of the museum, alongside a publication published by Trocadéro Editions, was featured most recently at Les Rencontres d’Arles 2012. In addition to her art practice, Cartiere works as a fashion photographer, and has had her photography featured in Dazed & Confused, Liberty Magazine, The New Yorker and T Magazine (The New York Times).

All images courtesy of the artist. © Alexandra Catiere