Paul Kooiker

Sunday

Essay by Brad Feuerhelm

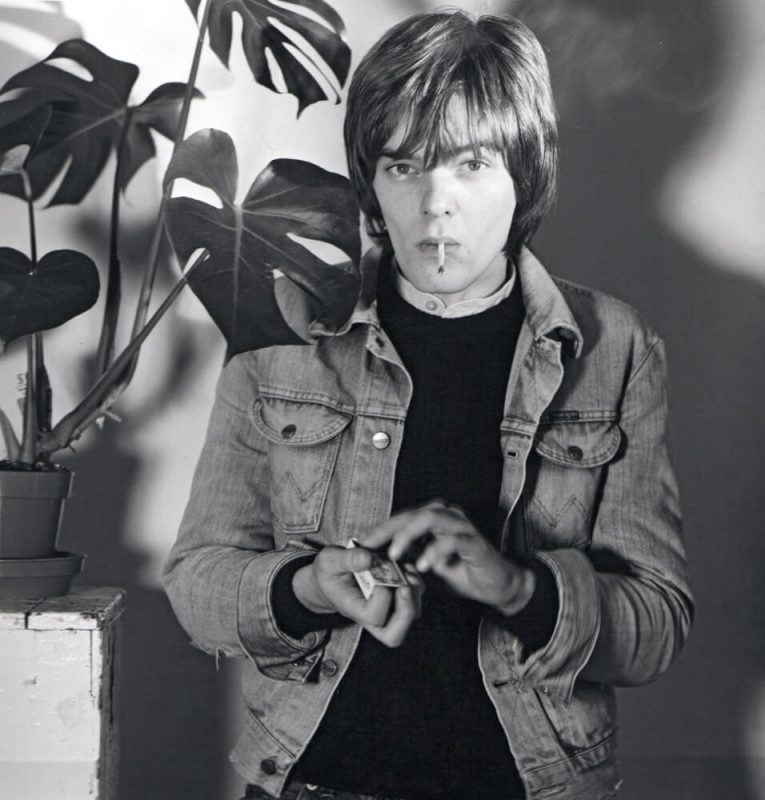

The work of Dutch photographer Paul Kooiker occupies an awkward liminal space somewhere between legendary filmmaker David Lynch and the surrealist Hans Bellmer. Yet, he claims that he draws no such direct references from the aforementioned stalwarts. As for inspiration, it’s “just life itself,” he states.

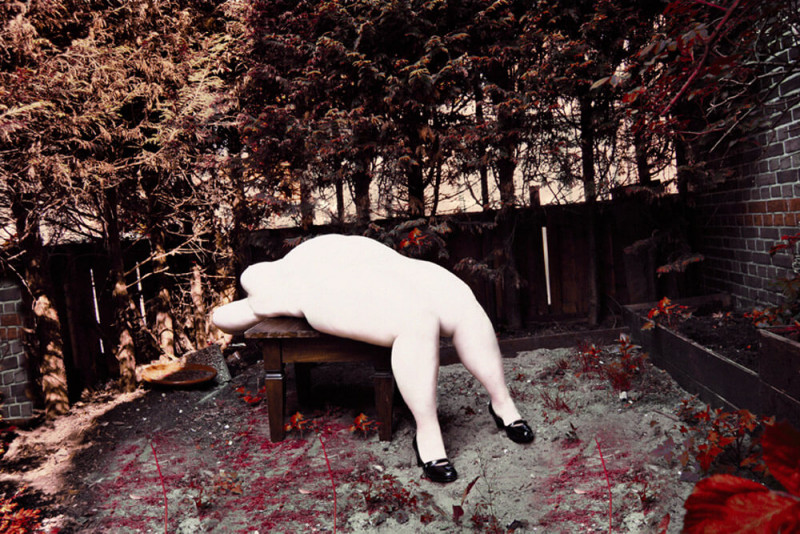

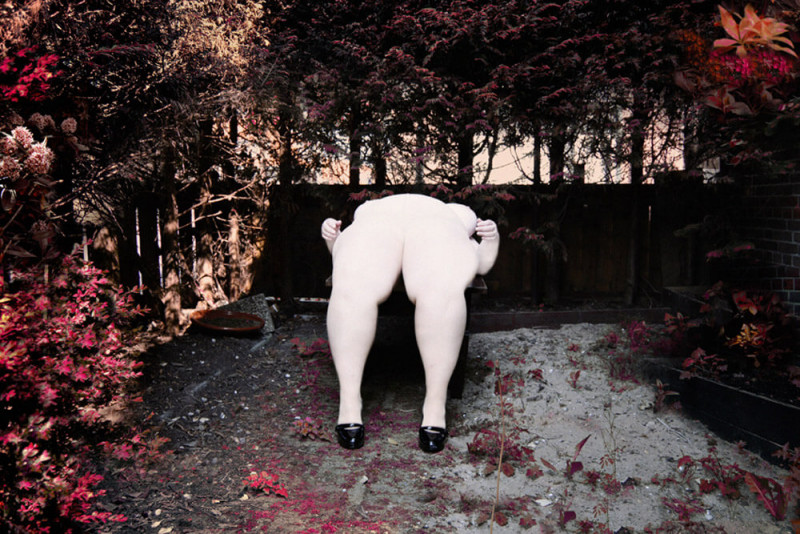

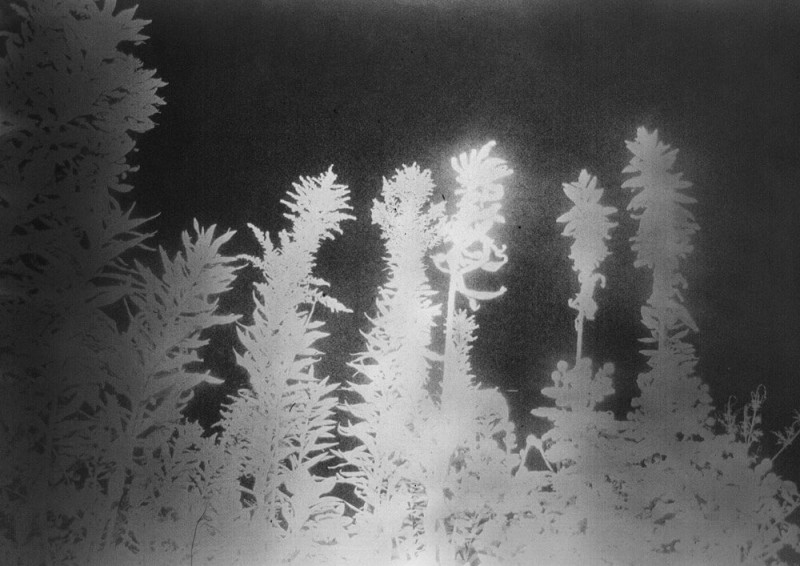

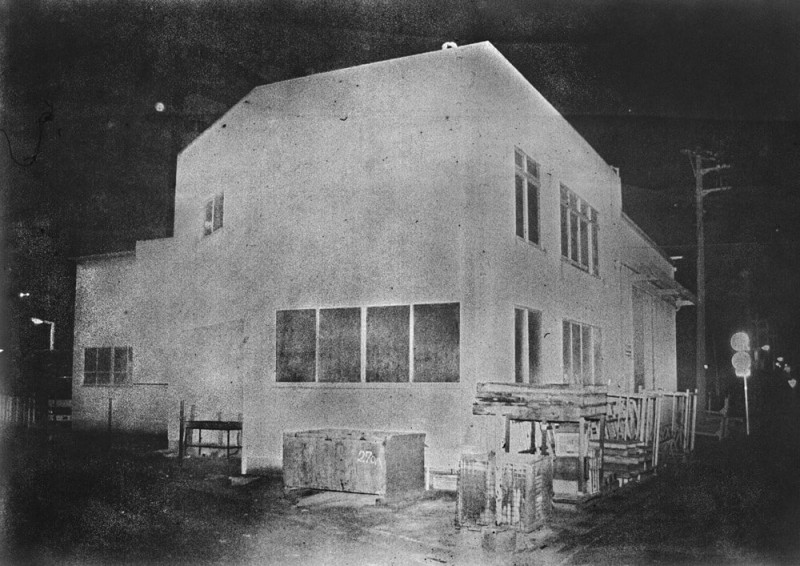

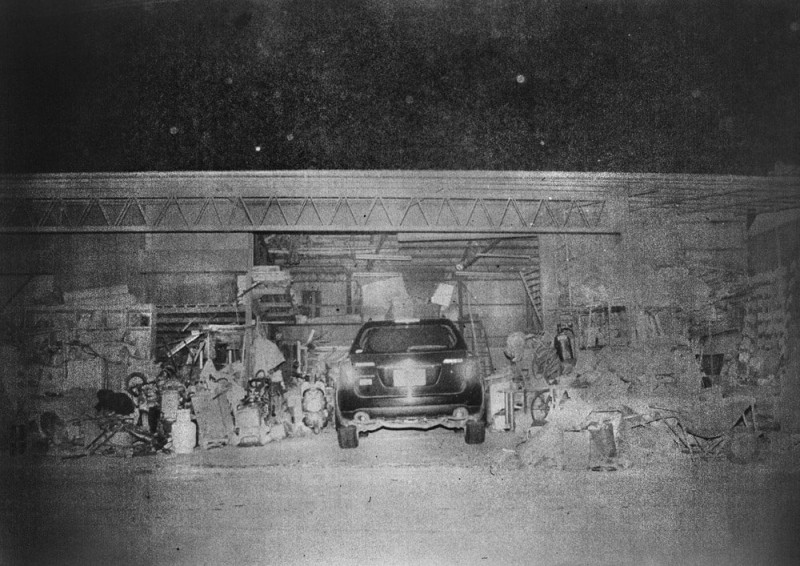

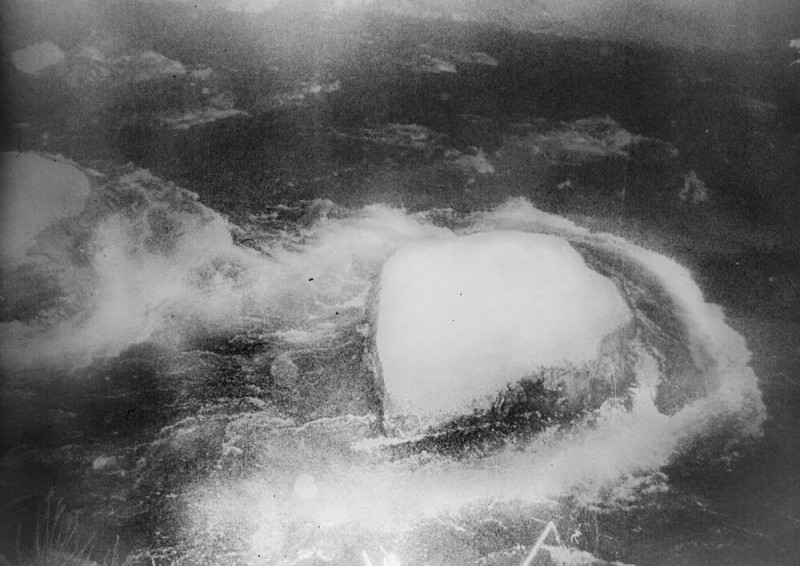

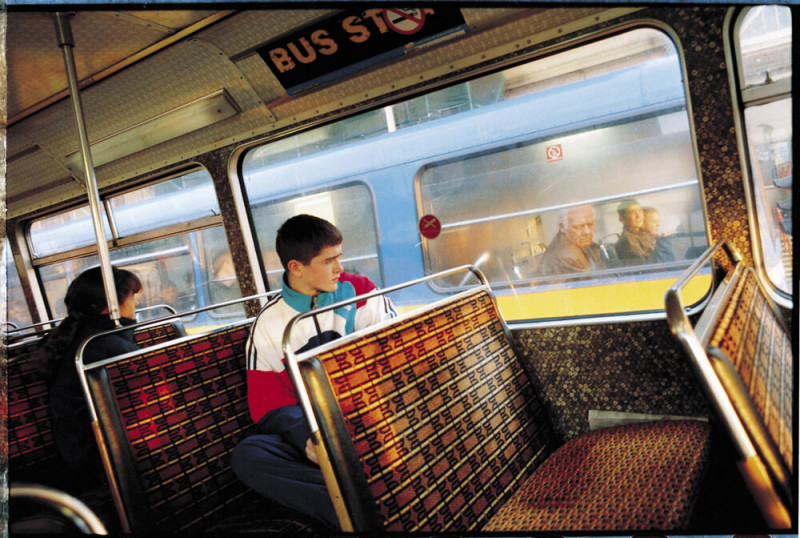

Still, his use of overly lush and vivid technocolour springs a fountain of false nostalgias, an anachronism that results in a kind of new noir. Such a palette evokes the membrane of a honey-soaked eye, blinking in the burning sunlight of a bright day. When the eye reopens the colour appears drained, but then it begins to materialise again in pantone schemes that resonate with intensity. It’s an optimising effect for the evocation of a memory that we may have only seen in a film.

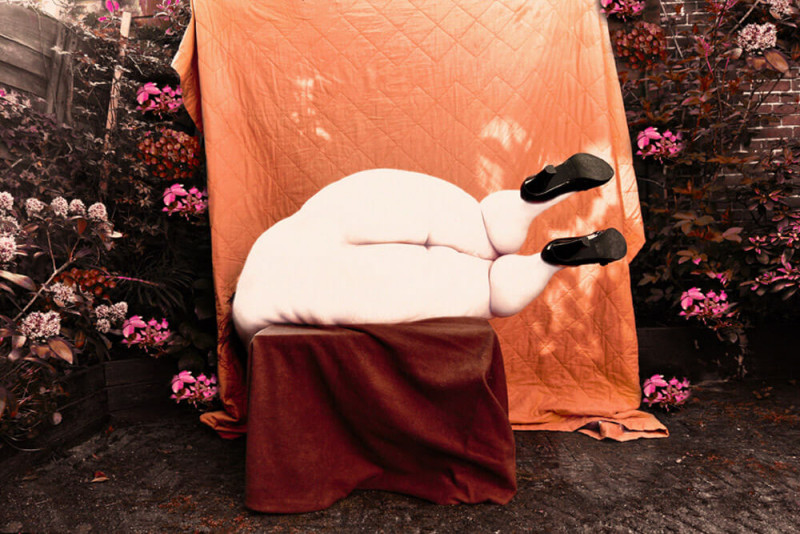

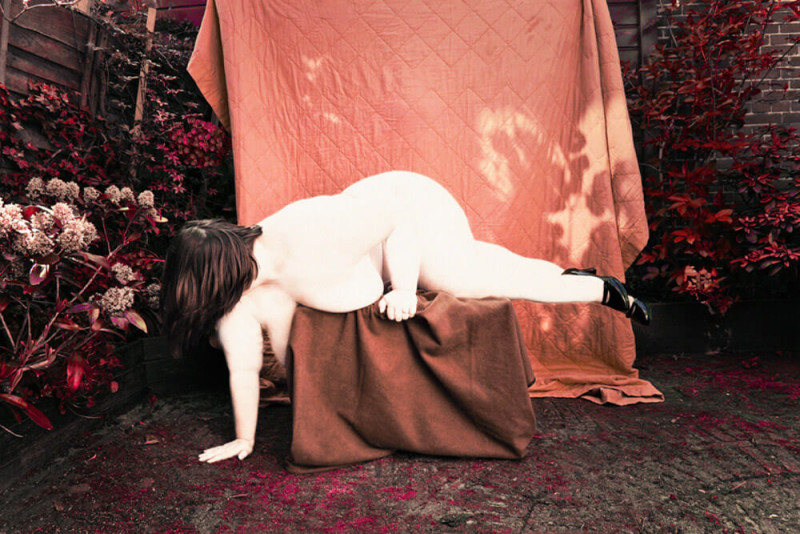

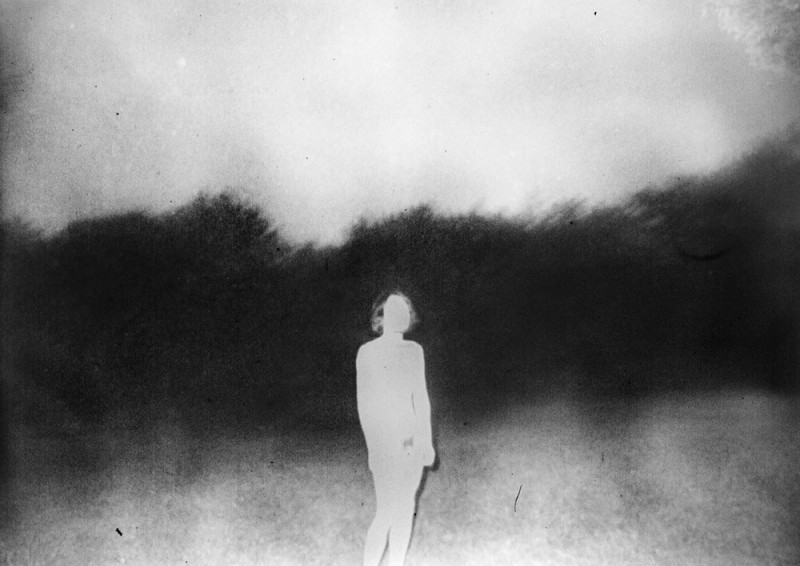

With regards to the spectre of Hans Bellmer, the work considers the mode of repetition and the sculptural if disembodied female form. “In general I am not interested in the single image,” explains Kooiker. “I like to show the study of a project. In the first instance the work is made for the book, the sequence of pages and the little changes of the model have a good rhythm, as a exhibition it would have a different seriality.”

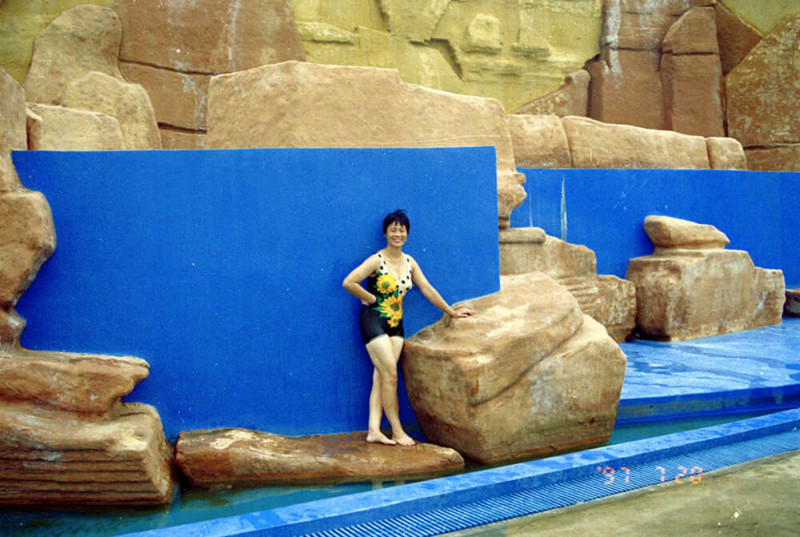

Kookier’s work, in one sense, elevates his model to the status of art in the manner of a still life. (“She could be an object instead of a woman,” Kooiker notes.) At the same time, the sculptural plinth upon which the body of the woman is photographed and thus viewed from multiple angles almost presents a case for several photographers working together during their ‘hobby time’ away from their families. Kooiker attests to this: “This element of the amateur contained within is apparent in all my work.”

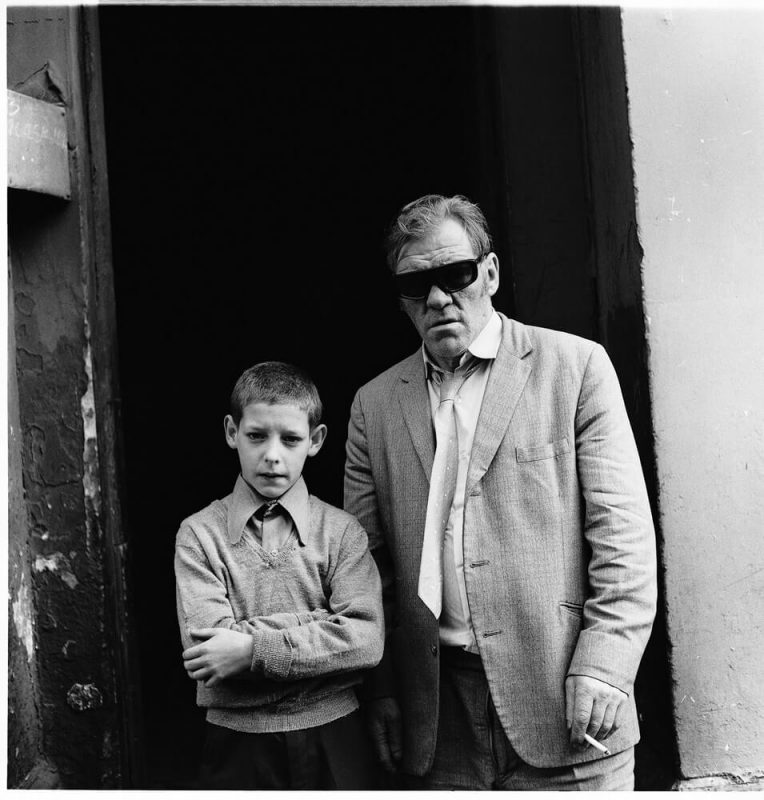

The erotic elements are still in place, but the images are far from explicit due to the genitalia not being represented. Nor are there the complicated incursions upon identity since the face is obfuscated for the most part. While we are at least lucky to escape the problem of model age, the subject within Sunday is also reminiscent of the women in Irving Penn’s Earthly Bodies series. Both Penn and Kooiker whitewash the models creating a somewhat ghostly suggestion. There is also a whiff of Bill Brandt in these distortions. André Kertesz as well. As we see, it is within the tradition of a certain European sensibility that these are images located.

There is also the notion that these illuminate a corner of Kooiker’s mind that he is being incredibly honest about. One could also say the opposite. One could read these as exploitative forms of a very specific hetero-European male practice of art making. It could be that the objectification factor and the loss of control through the model’s posing are at odds with clear presentation of its intent outside of the libidinal re-arrangement of female flesh ad infinitum and in tight quarters. It would not be an unfair assessment but the potential is not as resistant as the artist may wish.

Despite its subtle nuances, it does and will provoke a reaction on the part of its audience. Past the initial grappling with the large format of the work and satirising color effect, it leaves one questioning the pattern and its insistence on the body and its politicised body within the tradition of contemporary art and culture at present.

In further exchanges with the artist regarding these issues, Kooiker refutes the suggestion that the use of a more voluptuous woman might be based around the formalism in his work, or the fact that the softer, larger form could potentially be easier to produce a new tableaux with. Nor is it, he says, simply down to the particular model that being available on the day of the shoot. “This is a very special model,” he says. “She understands what I want. Why I did I use a larger model for this series? I cannot directly answer this. It is also a mystery for me.”

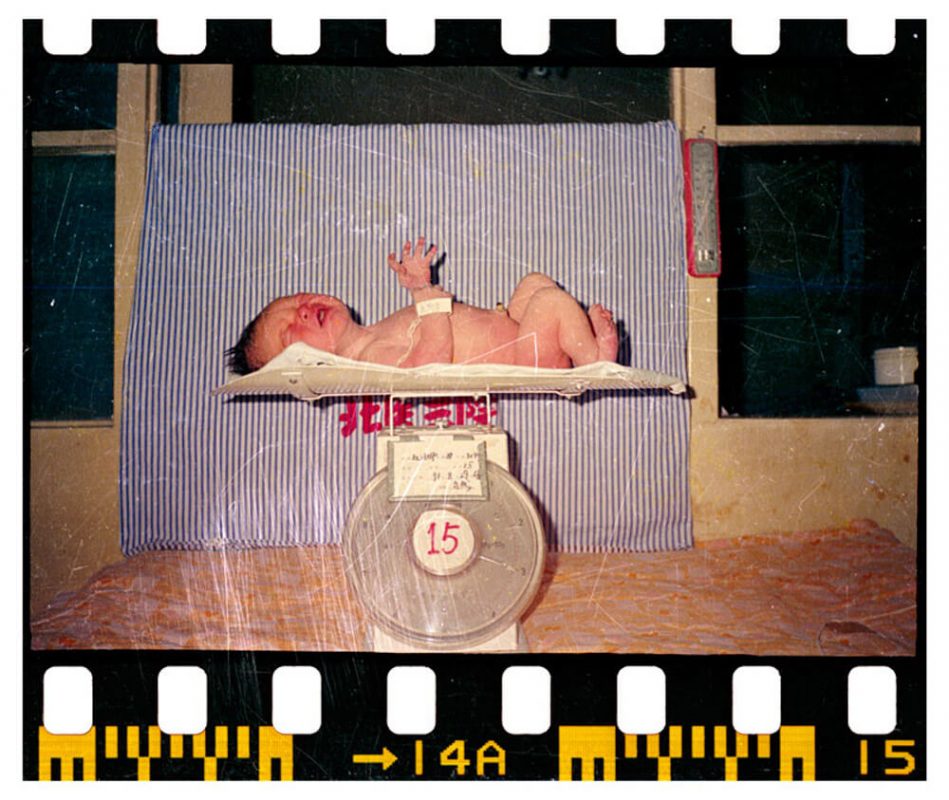

Likewise, he opts not to explain his intentions – for better or worse. He has even said that being conscious while making work that the female subject should be examined in a certain way that takes meaning to the edge without exploiting it is of no concern to him. Clearly though, the notion of the abject is not lost on Kooiker. He speaks of his early interest in medical photography which resulted in his photobook Utrecht Goitre – an incredible selection of unique historical images from a pathology clinic in Utrecht alongside his own photographs that depict strange but not uncommon features such as birth marks and moles, cracked heels and baldness. The grand themes of the grotesque and abject are of course valid forms of artistic currency and Kooiker’s specific form of voyeurism straddles certain uncomfortable truths.

There are quivering tensions between subjectivity and objectivity, beauty and ugliness, seduction and shock, observing and being observed that reside in the whole image. Kooiker’s work then is a revelation that obsession and the quest to qualify images of personal, near-obliquely-diaristic projections of to create an atmosphere of uncertainty is worth the identity it assumes within this series. The questioning of the work becomes reflexive. It forces the audience to think and leads to questions directed towards ourselves, of our perceptions of human form, of women, of ‘the other’ and of our own forced nostalgias that are created by colour or sensory perceptions of sound or smell. ♦

Paul Kooiker (1964) was born in Rotterdam. He studied at the Royal Academy of Arts in The Hague and at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam. Since 1995 he has been teaching at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam. In 1996 he won the Prix de Rome and in 2009 he was awarded the A. Roland Holst Prize. Paul Kooiker’s work has been exhibited widely including group shows held at Maison Européene de la photographie, Paris; Fotohof, Salzburg; Kumho Art Museum, Seoul; Arsenale Novissimo, Venice; Zabludowicz Collection, London. Solo exhibitions since 1996 include those held at Kunsthal, Rotterdam; Vleeshal, Middelburg; James Cohan Gallery, New York; Fries Museum, Leeuwarden, Foam Fotografiemuseum, Amsterdam; Gemeentemuseum, The Hague; Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Paul Kooiker has published several books: Utrecht Goitre (1999), Hunting and Fishing (1999), Showground (2004), Seminar (2006), Room Service (2008), Crush (2009), Sunday (2011) and Heaven (2012). Between 2007 and 2009 he published fourteen issues of Archivo, a bi-monthly photo journal curated by himself and gallerist Willem van Zoetendaal.

All images courtesy of the artist. © Paul Kooiker