Marten Bogren

Tractor Boys

Essay by Christian Caujolle

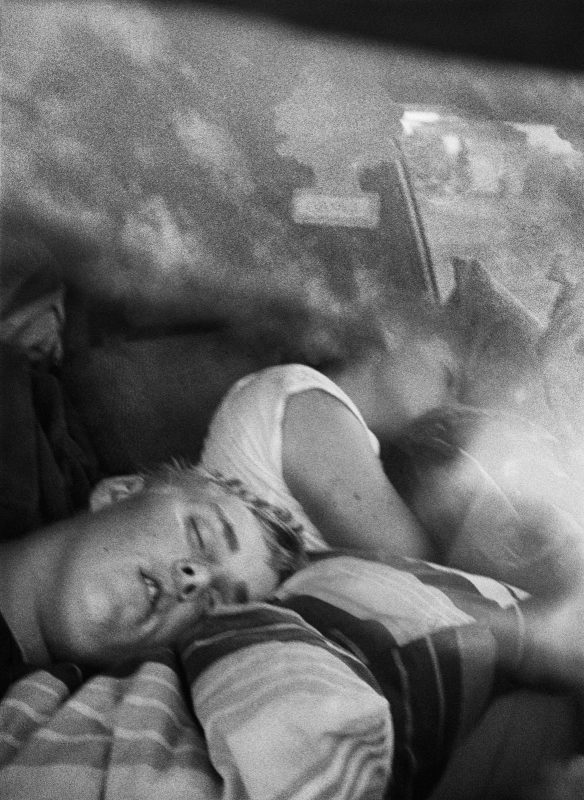

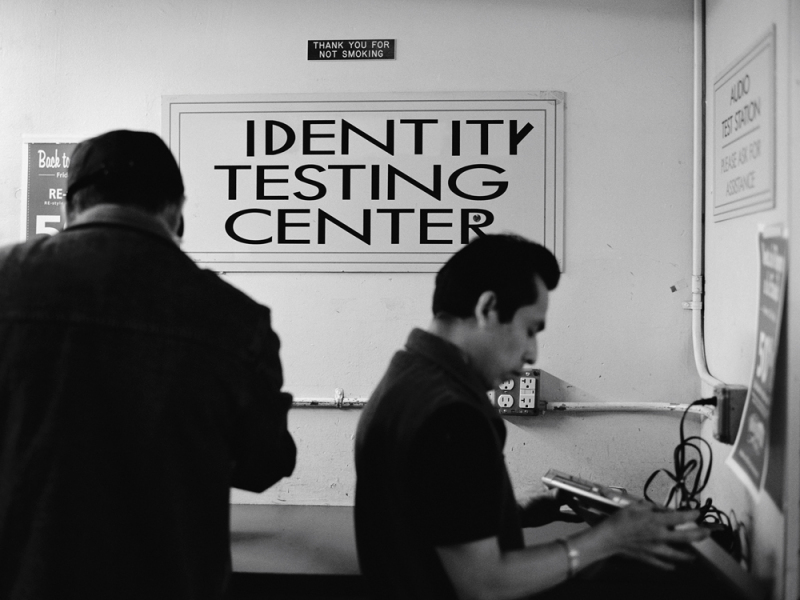

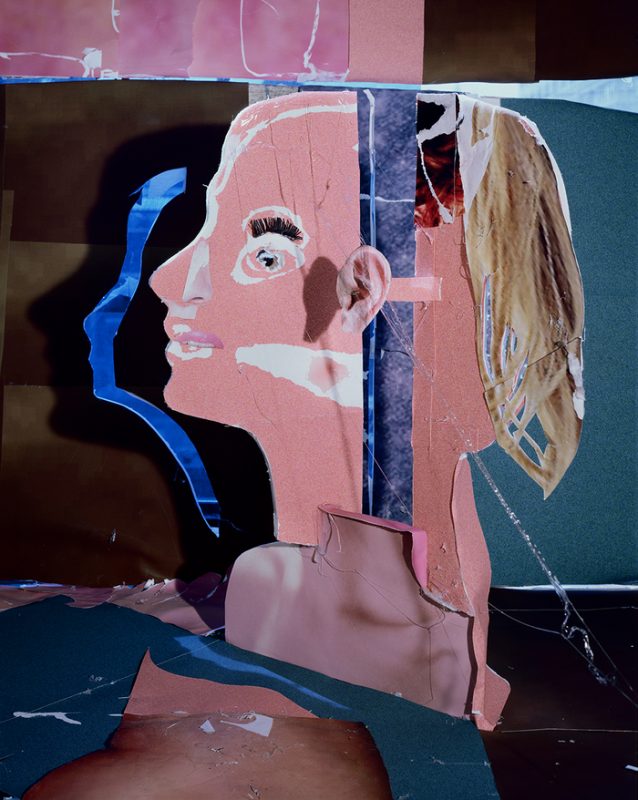

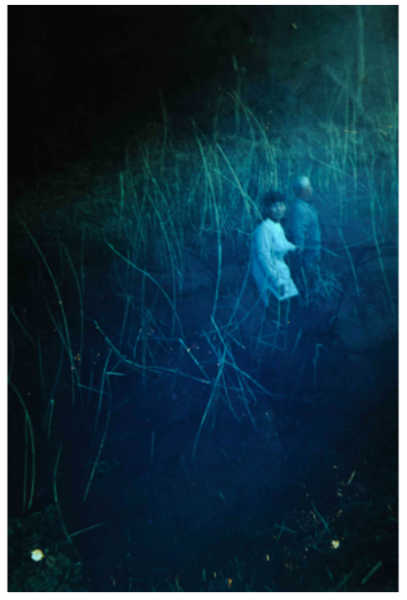

Exhausted, placated, perhaps both. Behind the car windscreen, through which the photographer gently catches them unawares, they are sleeping. A grey light, filtered, a visible texture, specks of brightness, everything is softness. Left by themselves, they seem even younger than they are, off in a world of their own, the reflections separating them from our world even more securely than the glass of the windscreen.

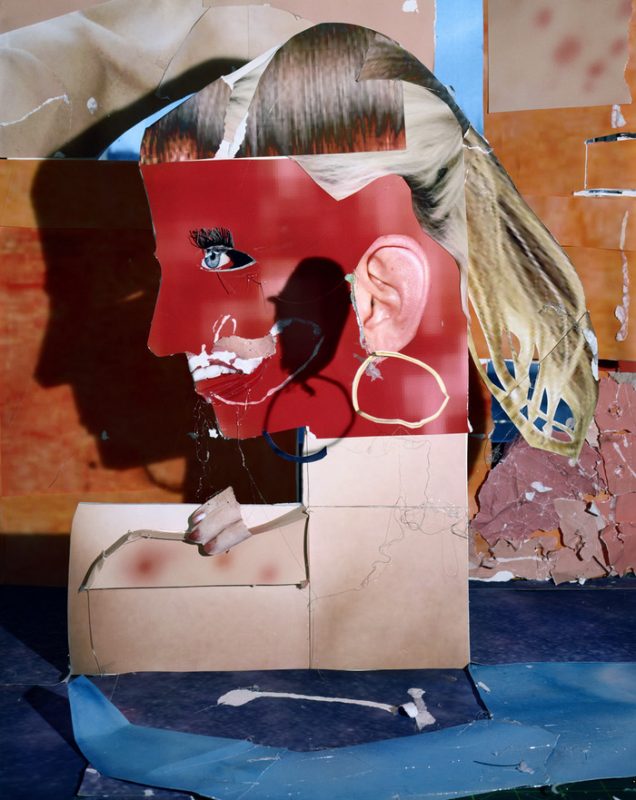

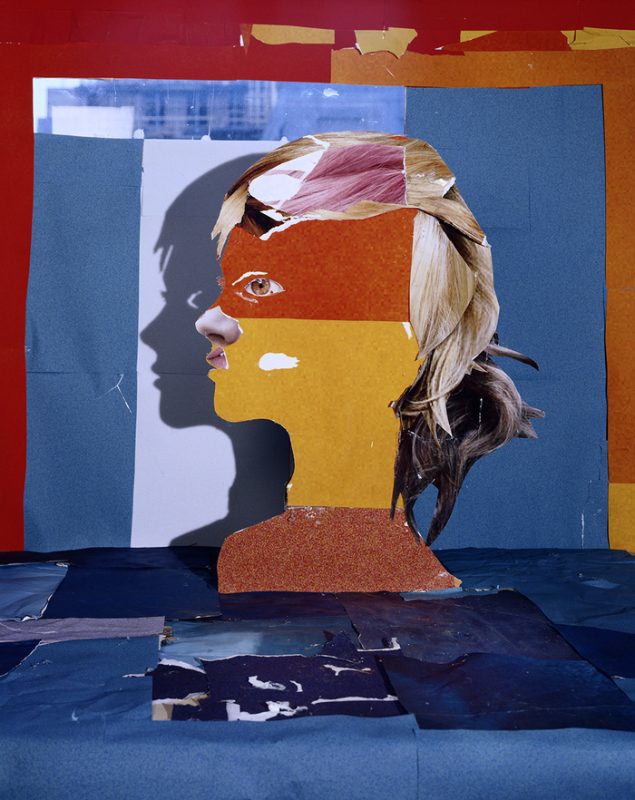

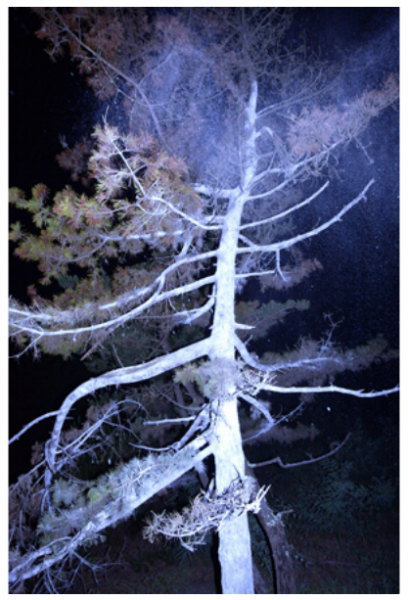

The explanation lies in the other images, the ones that set the scene. The viewpoint broadens out to a coniferous forest that shimmers in the light, to large areas of deserted nature, to these northern territories which breathe fully and whose nakedness, which can be exhilarating, is no less painful for teenagers than the boredom that lies in wait. They need to release the energy within them and explode this boredom eating away at them. And so, they get hold of these ‘tractor-cars’, these cars transformed into agricultural tools; they tinker with the engines to unleash the speed and the screech of tyres, they use excessive amounts of oil, all in order to indulge in the intoxication of speed.

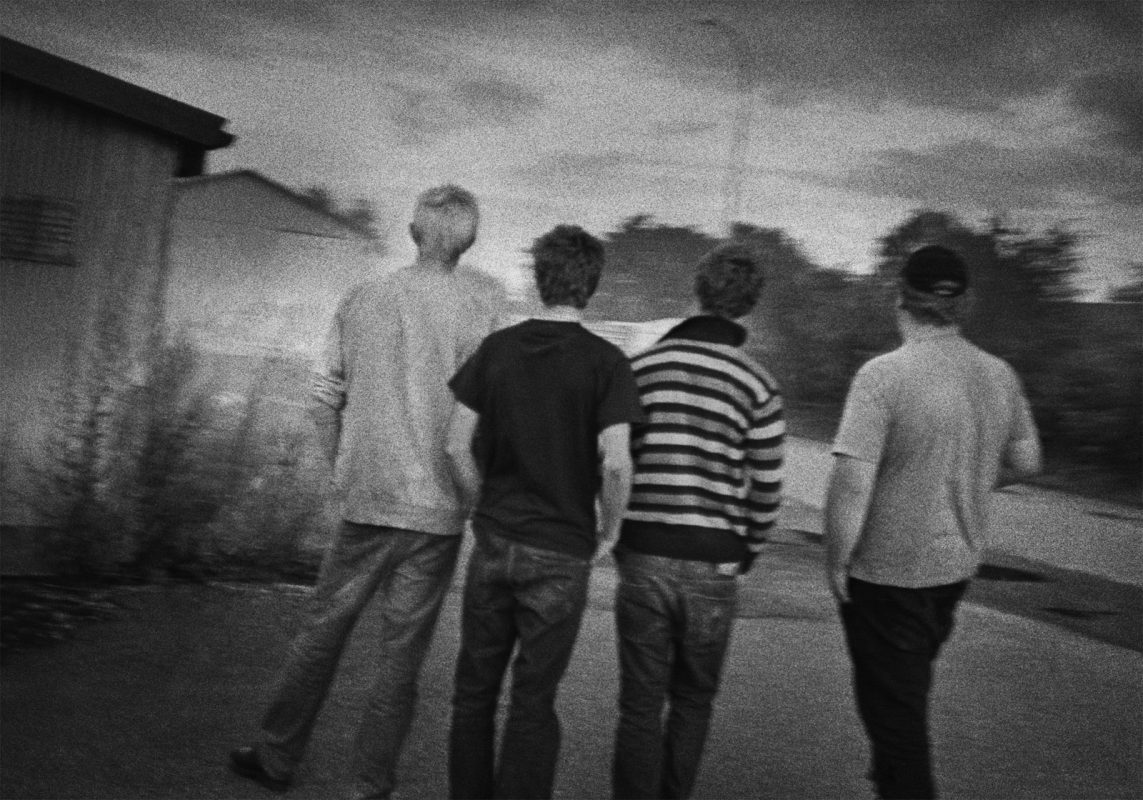

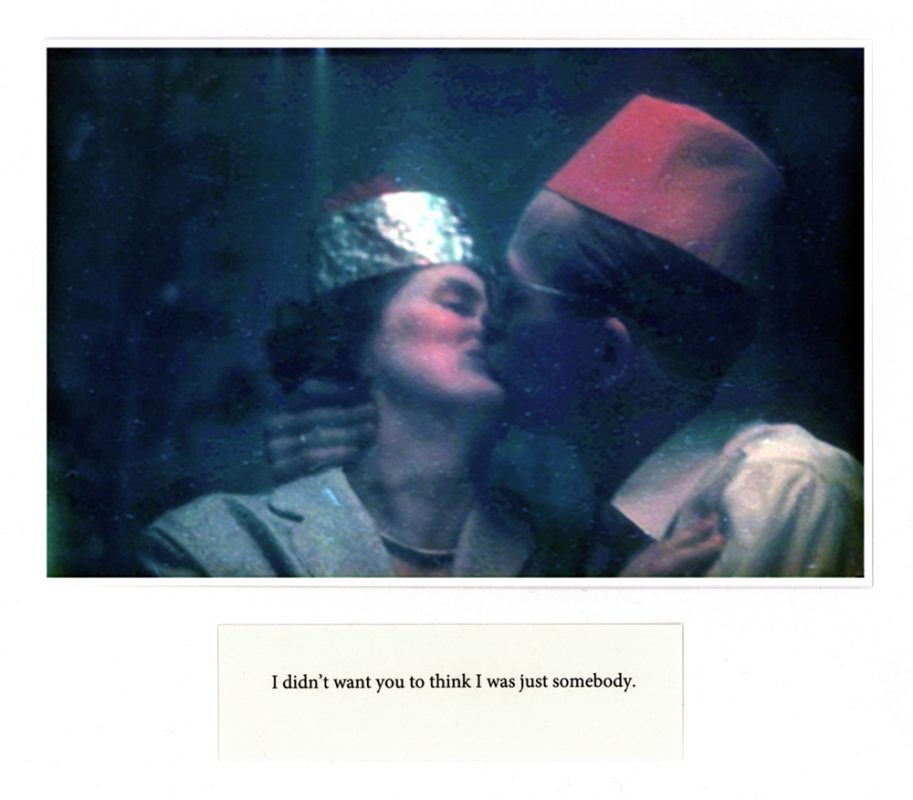

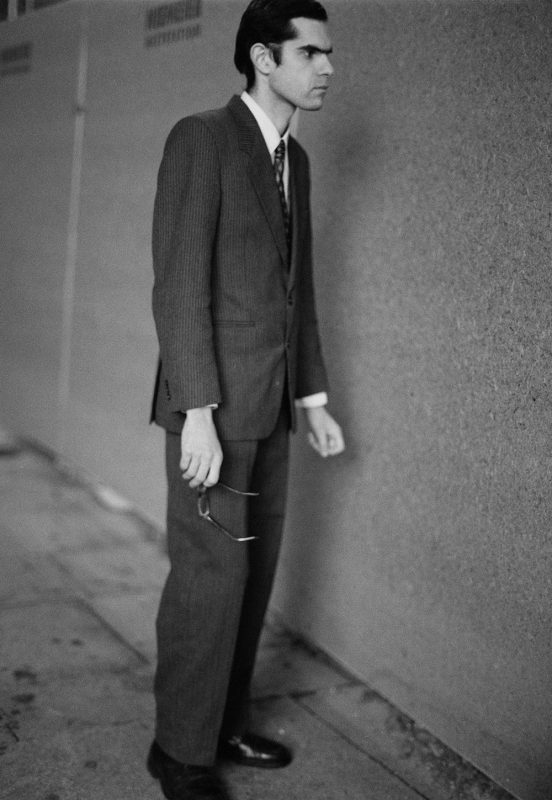

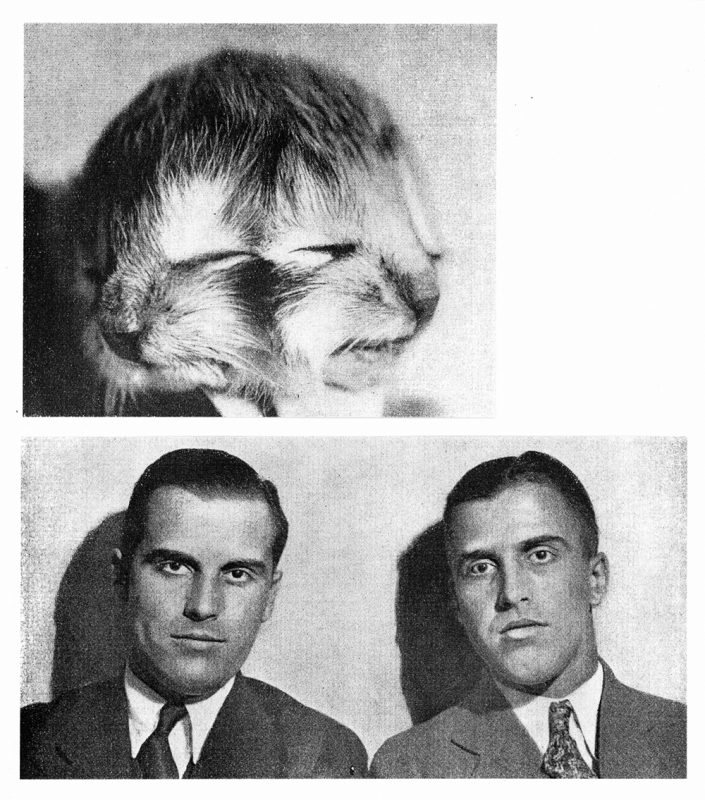

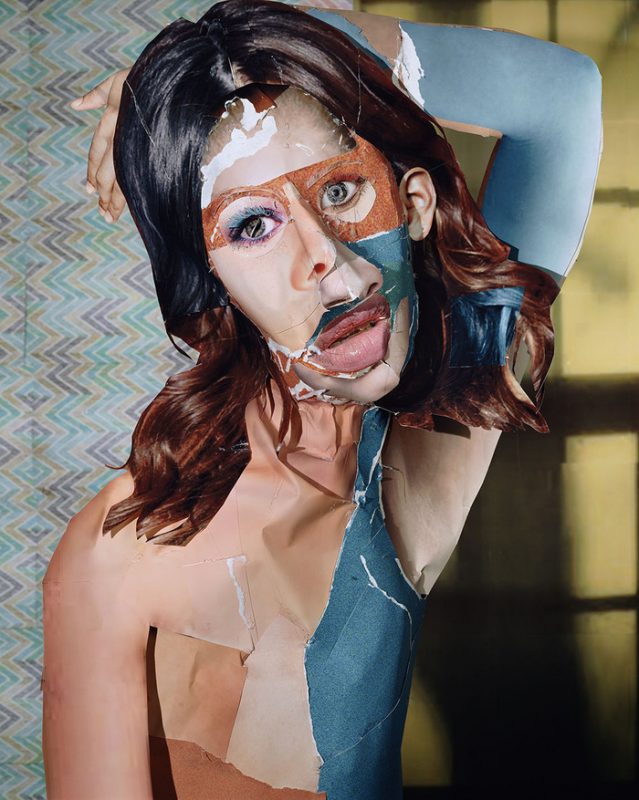

These kids present themselves as tough guys to impress the girls. They meet up to confront themselves and others – to try to define who they are in a world that doesn’t constrain them. They smoke gallantly, they walk with a swagger, they take risks, but something isn’t right. As in all these complex moments of adolescence, childhood and adulthood clash, emerging as a basic and impossible contradiction.

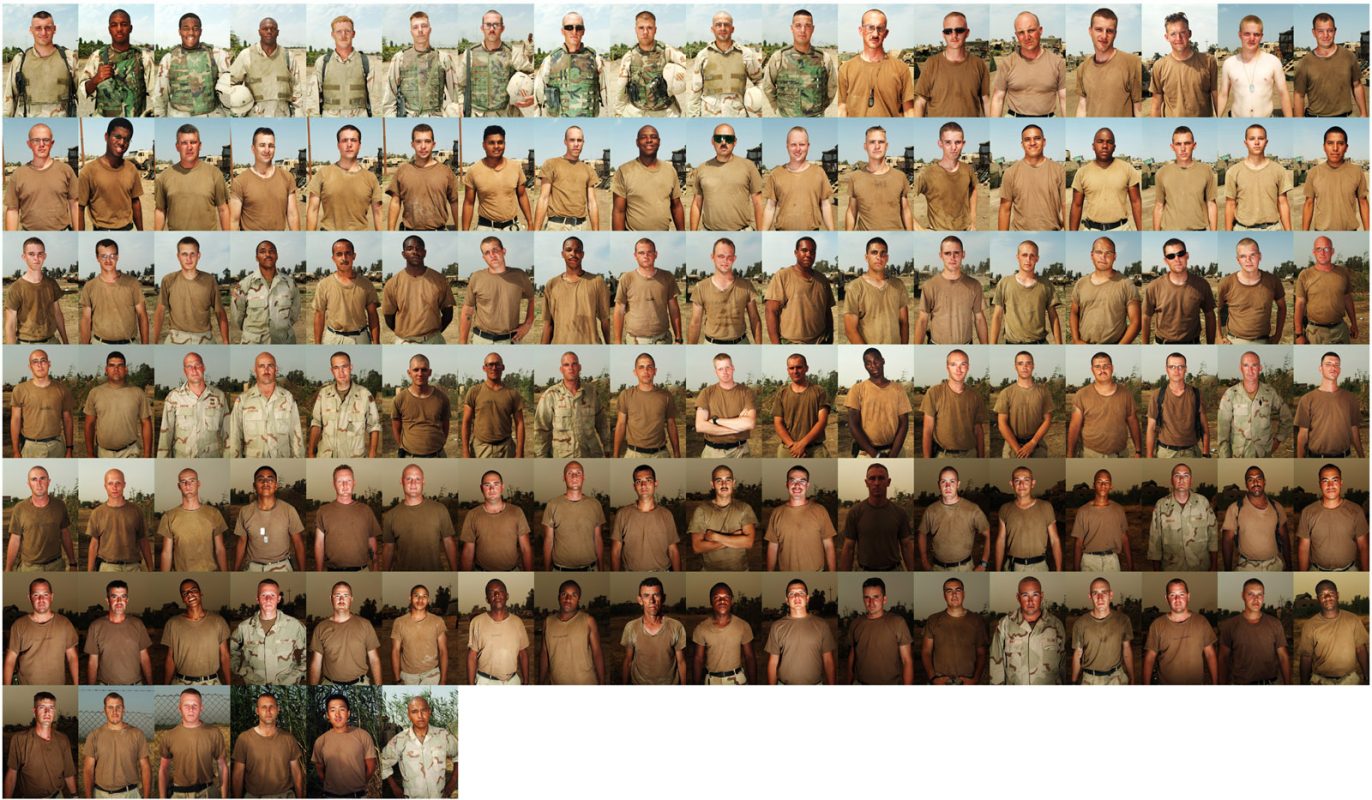

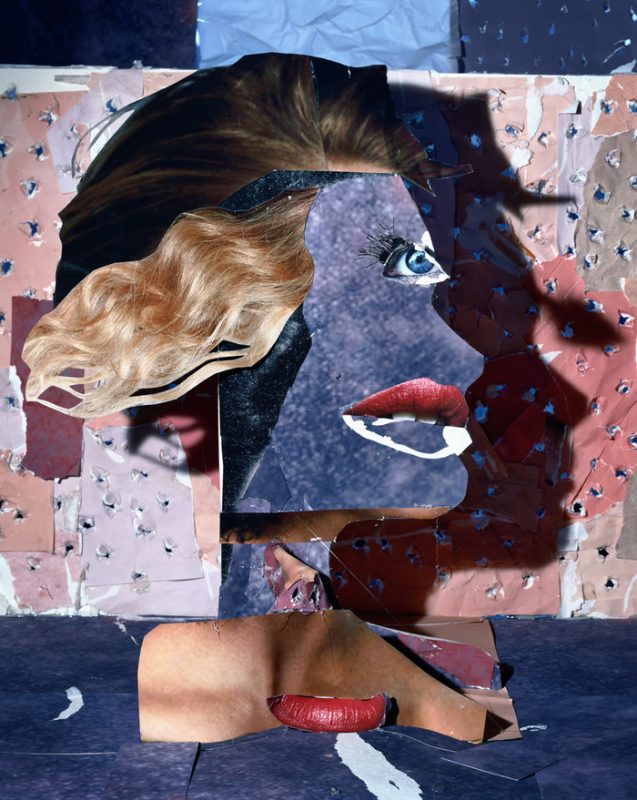

All of this has the air of a spectacle staged by actors. What matters, and what makes this work so compelling, is the way it is seen. Photographer, Martin Bogren, has been accepted into a world clearly prohibited to adults. He doesn’t let himself be carried away by the exuberance of what he sees, or the excess, nor does he allow any complacency. A silent witness – it is truly remarkable that these images of moments of fury should be silent to this extent – he observes. In compositions as flexible as they are precise, as natural and instinctive as they are understated, he endeavours to report what he sees and what he perceives. At every moment he finds the right distance, one which states nothing other than the subjectivity of his perspective and he succeeds in combining a documentary approach with a sensitive affirmation of his vision. One thinks, of course, of all those photographers who – from Robert Frank onwards, from Anders Petersen to Michael Ackerman – have known how to give us the gift of their way of looking, telling us that they wanted to show nothing more than what they needed to show and to say.

Somewhere between a group portrait, delicately isolating faces and expressions, and a chronicle of a life dreaming of going as fast as possible, the photographer manages not to disrupt the world into which he immerses himself, with decency, with attention and acuity, and with respect, without judging – holding his breath. We feel this in the attention to light, the grey tonality contrasting calmly with the intensity of the action.

First kisses and first flirtations, cigarettes inhaled deeply, tracks that wind across the tarmac, hair blowing in the wind, life at breakneck speed – an episode repeated by appointment against the backdrop of the smoke of the factories. We cannot know anything of this world, it is not for sharing, it belongs to these young people who are leaving childhood and want to believe that they have become grown up. But the photographer, because he has understood the position that he should take, half-opens the door. He marks these minute moments that make sense and that we want to connect to each other to try to reconstruct relationships that we can only understand through what we can draw from our own memories.

There is something unreal and yet very present in these images; something that truly resembles photography in its dependence on reality. There is also a peculiar music, perhaps resembling that of The Cardigans, the band that photographer Martin Bogren toured with, and whose track Been It begins with the words ‘baby boy’. ♦

All images courtesy of Dewi Lewis Publishing. © Martin Bogren

—

Christian Caujolle teaches, writes, curates exhibitions and festivals on photography. He was an art critic for the daily newspaper Libération in 1979 and focused on photography. In 1981 he became picture editor of the same newspaper and continued to write about photography books and exhibitions. In 1986, he created VU’ Agency, the first ‘photographer’s agency’ and ten years later he established the VU’ Gallery. He left VU’ in 2007.