Bill Henson

1985

Special book review by Daniel C Blight

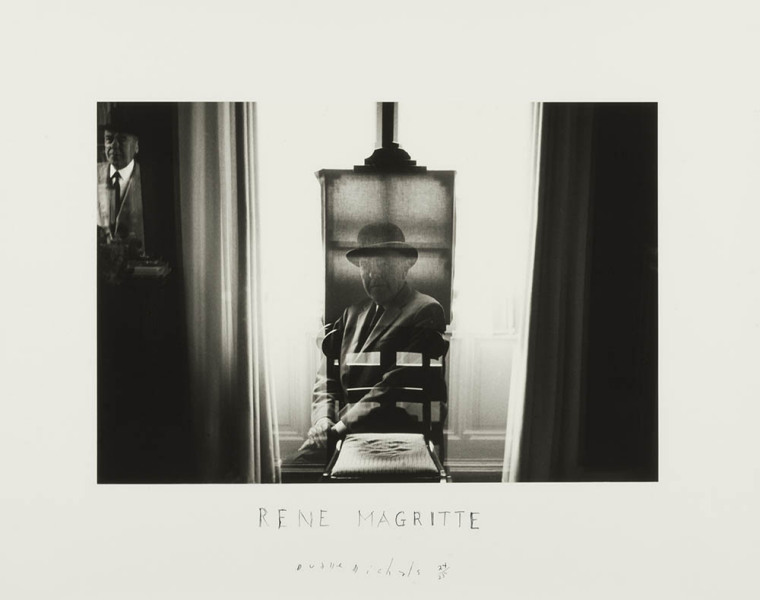

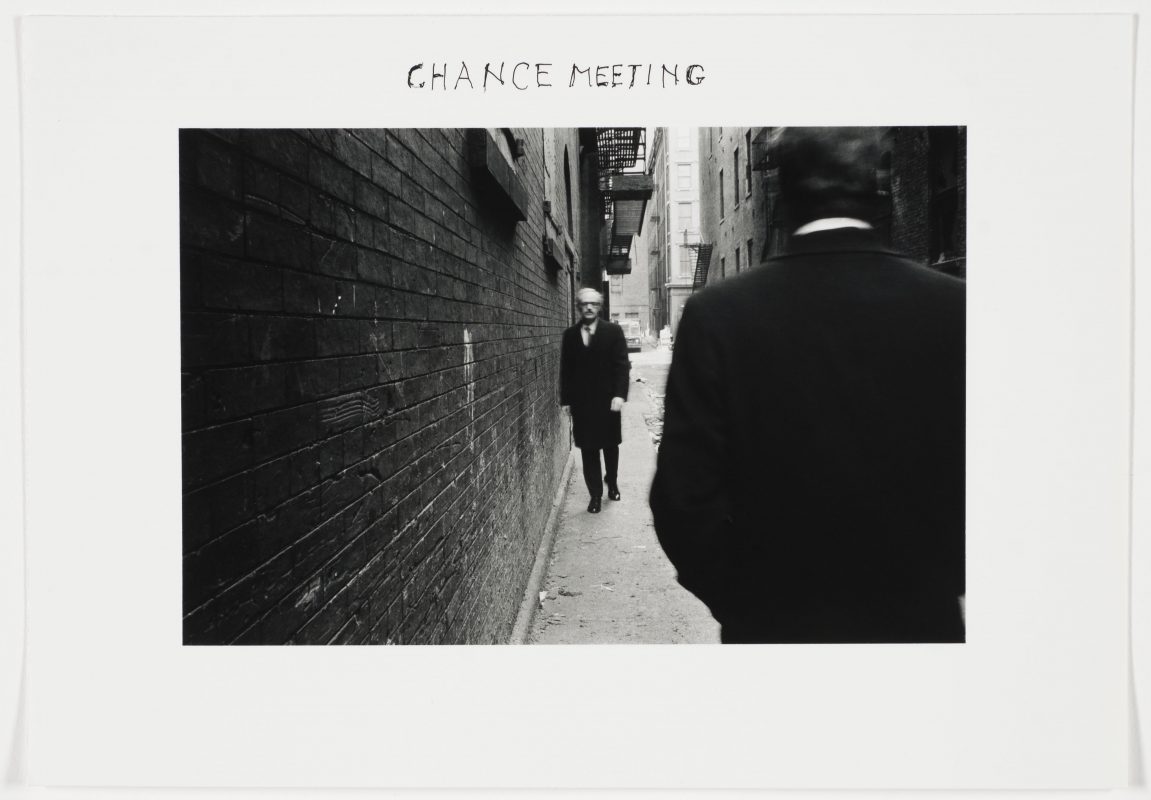

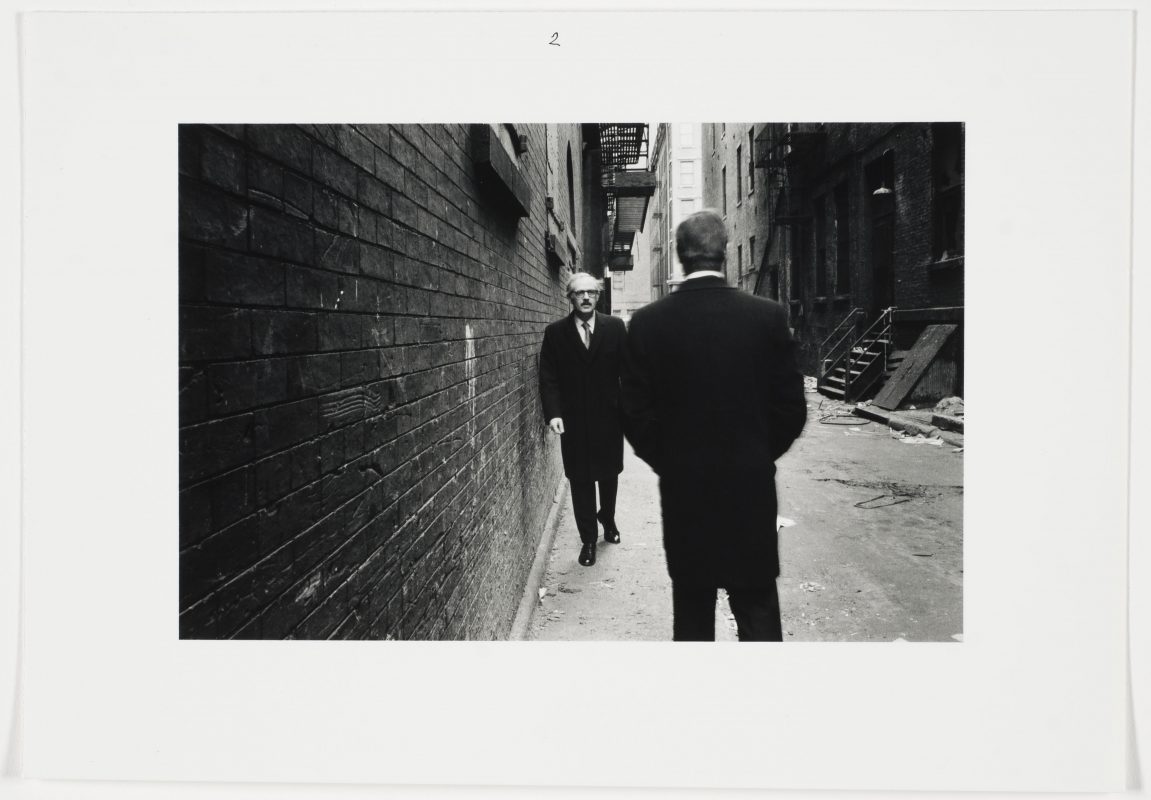

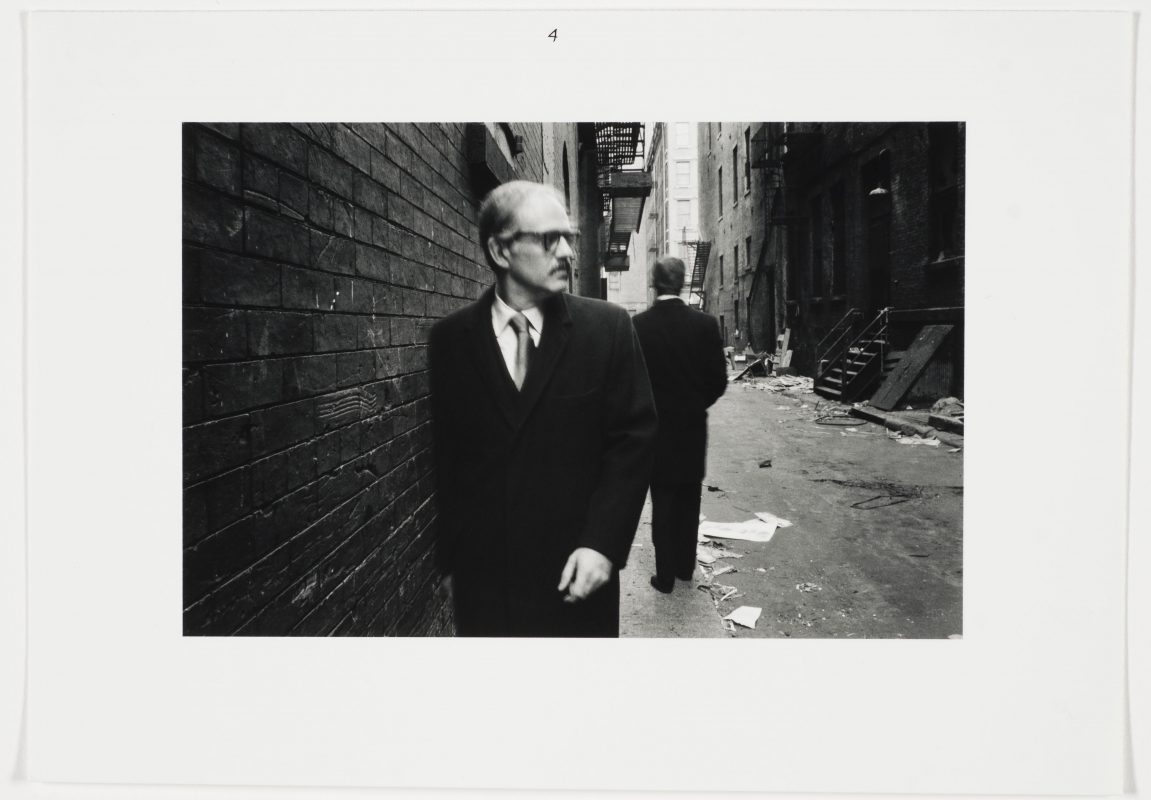

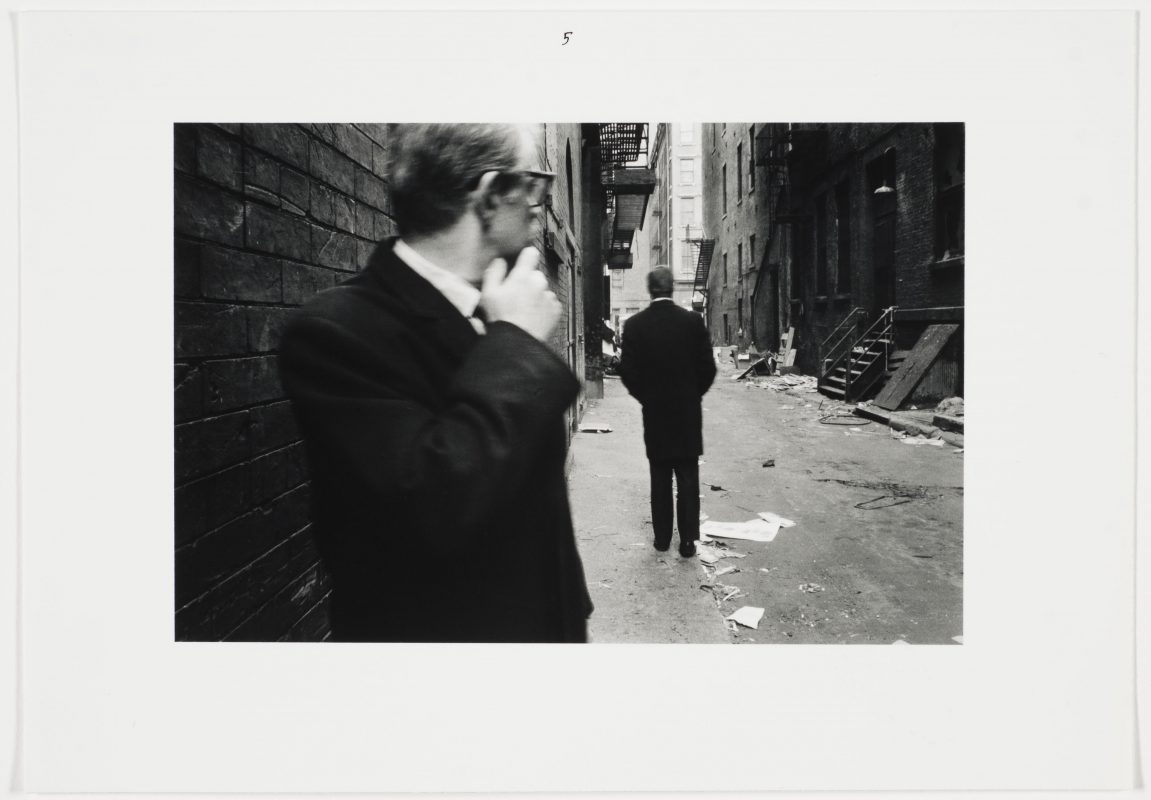

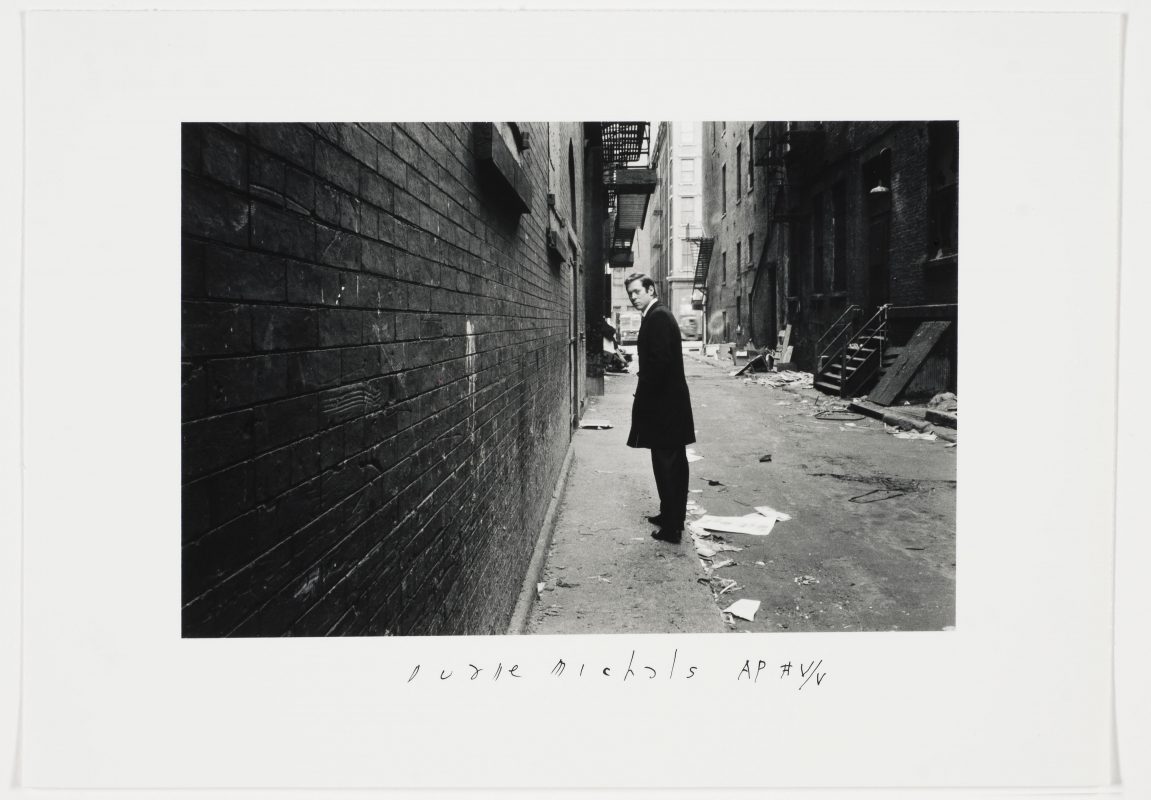

Bill Henson stands in twilight. Or so it has been suggested. In his 2006 exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the photographer was described as having created many grand things, among them: a ‘modern mythology’, ‘quiet melodrama’, ‘a contemporary reworking of the sublime’ and even ‘seemingly supernatural events’. It is not within these crepuscular tautologies that Bill Henson really stands, though. After all, they were written eight years ago. Now and before then the photographer was more likely outside, on his own taking pictures, away from all the verbose discussion.

Twilight is a very short period of time occurring twice daily. However, Henson’s work is not set in two determinable moments, nor a form of stasis, or even a particular stage of the day. Instead, these photographs might be asking us to look for something moving between what we have all managed to hide from at night, and therefore what we all fear from the day. Namely, exposure.

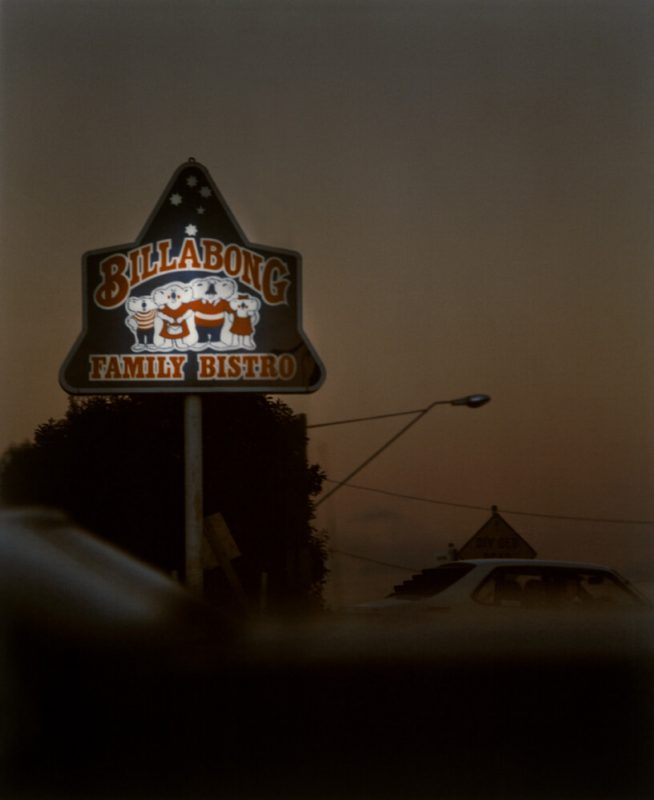

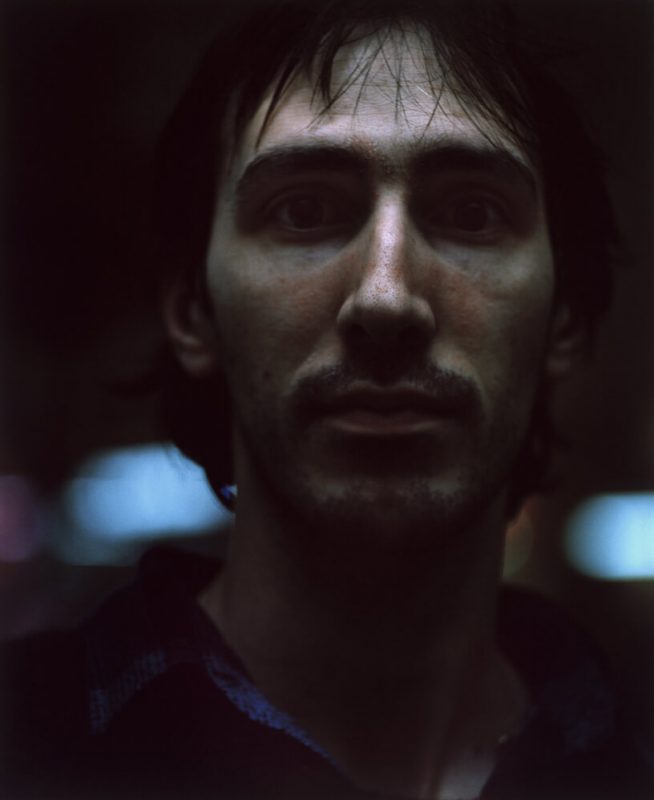

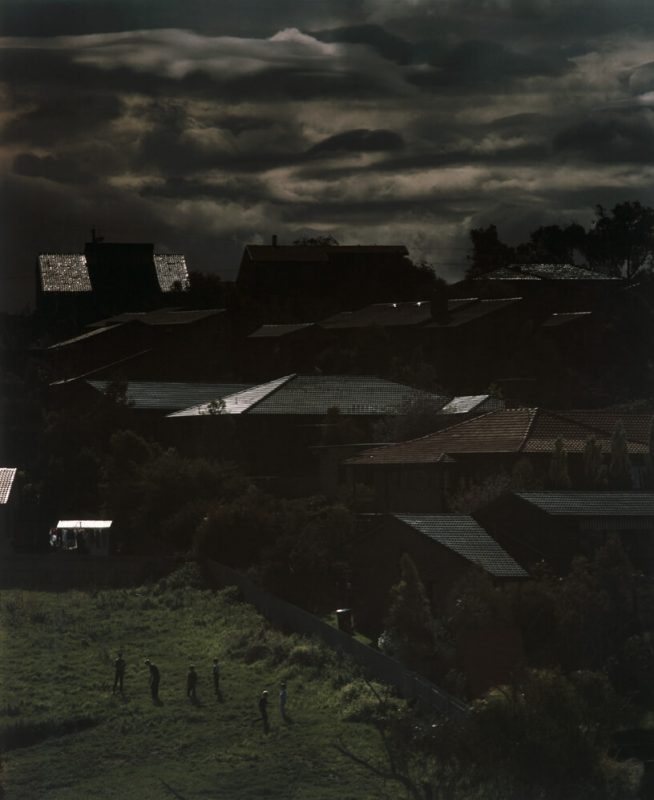

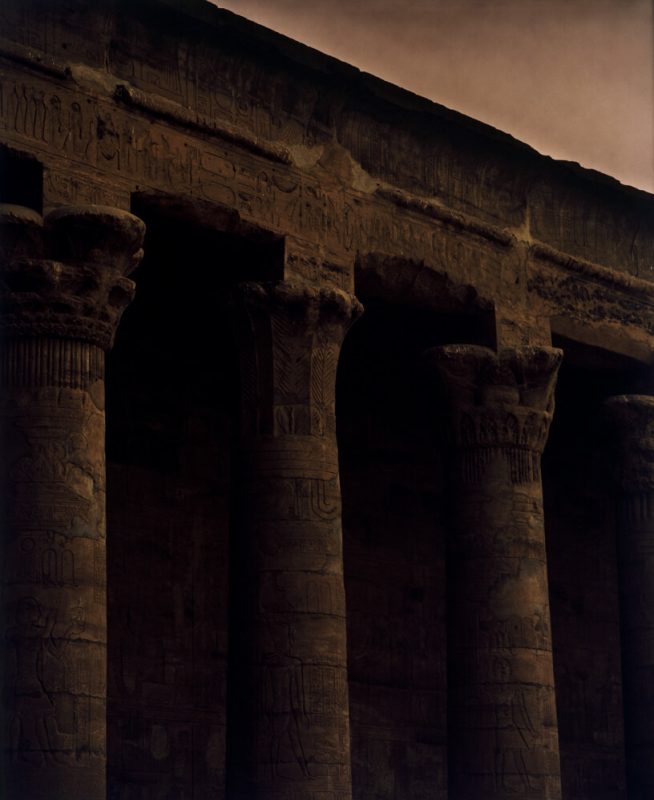

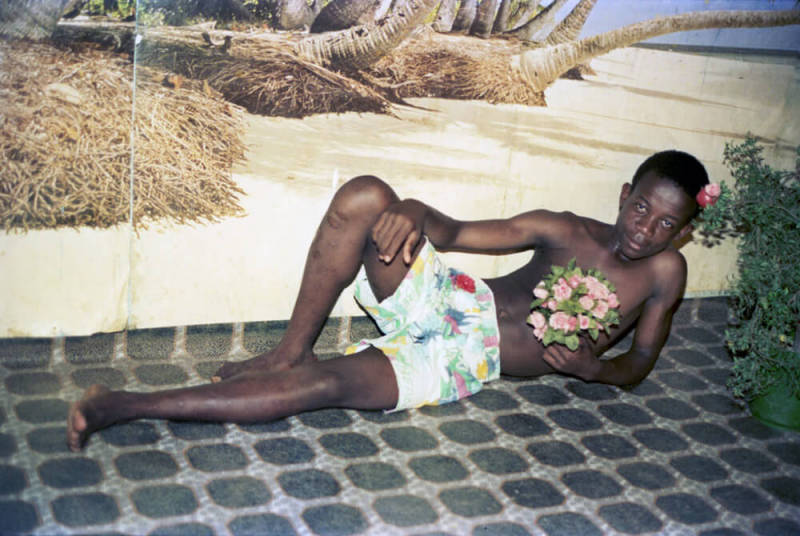

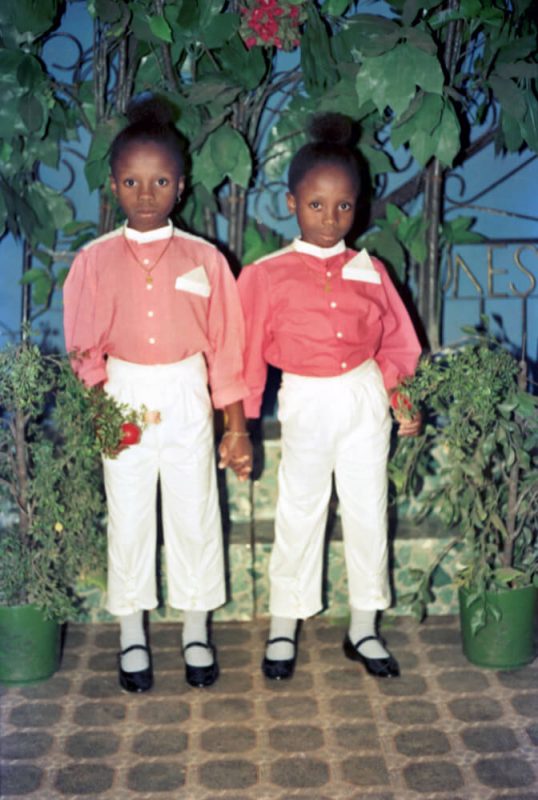

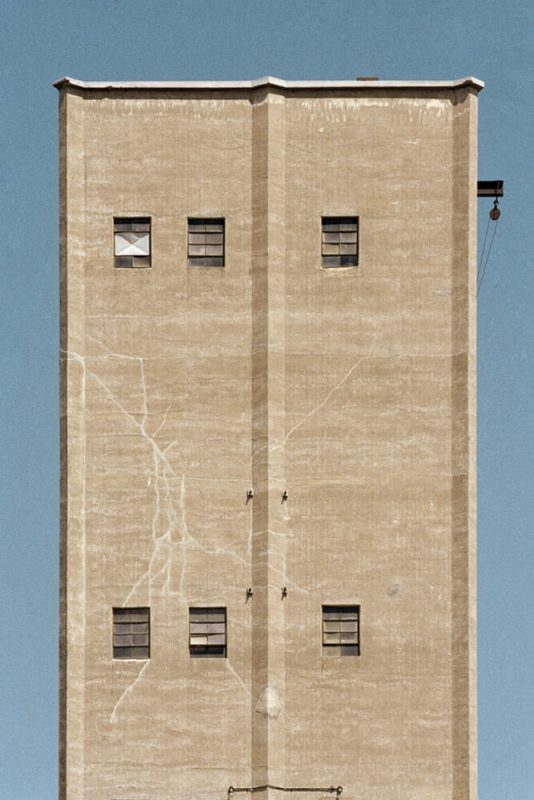

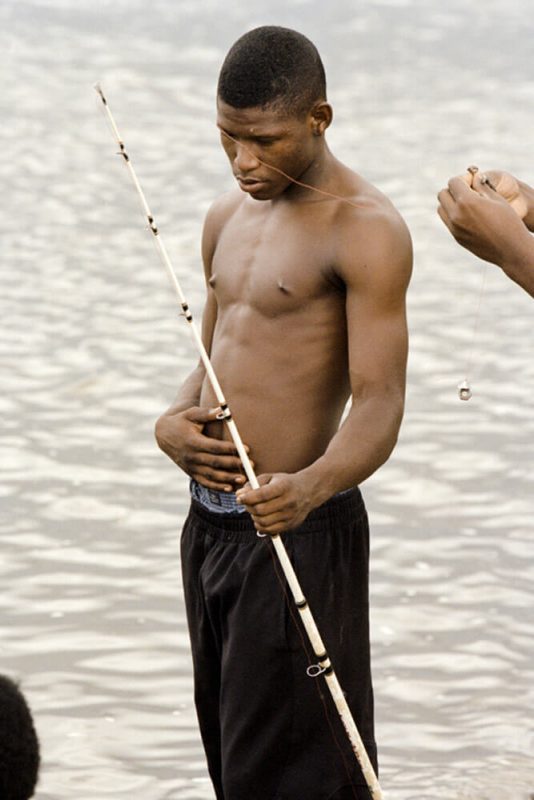

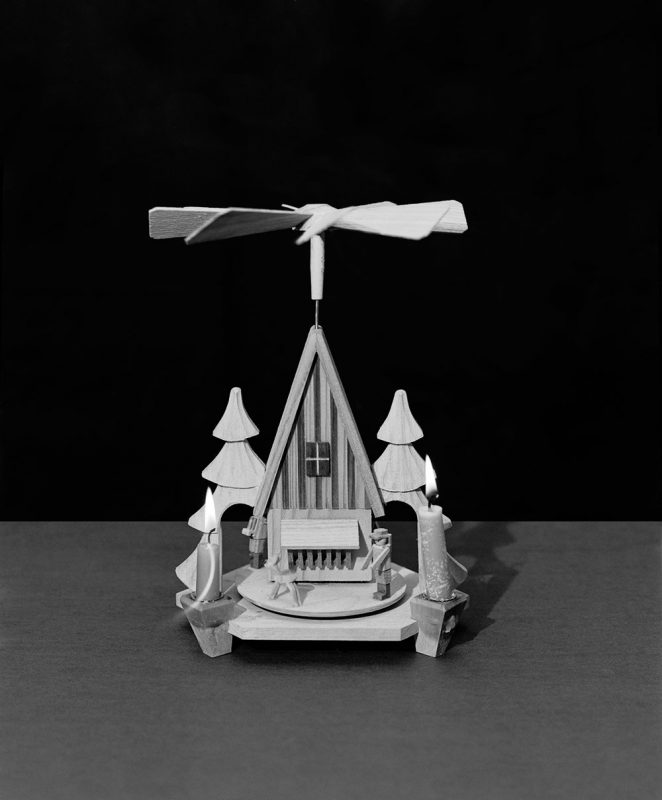

Henson’s camera has the ability, through movement and then poise, to render the best kind of sombre confusion. Henson’s images are subdued not in time, but over skies and through buildings, clouds, naked people, telephone pylons, pyramids and other familiar or extraneous abstractions. They are seemingly underexposed, but we can’t call them badly lit. Somewhere between the ambiguity of eventide and its gloaming opposite, Henson is a wonderer; one whose images intentionally do whatever they can to avoid stasis and perhaps clarity, within the confines of their static medium.

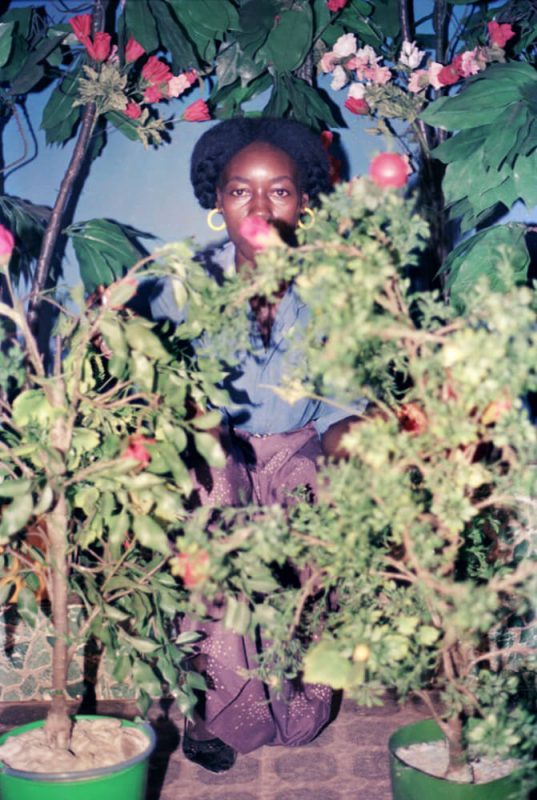

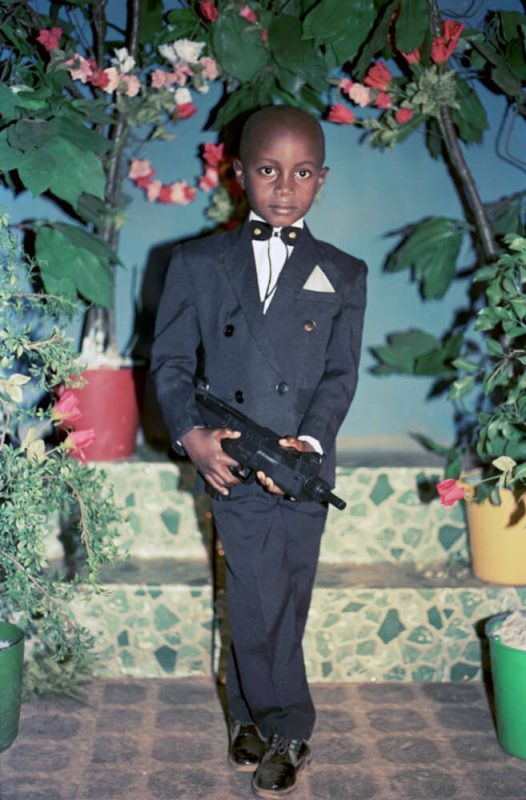

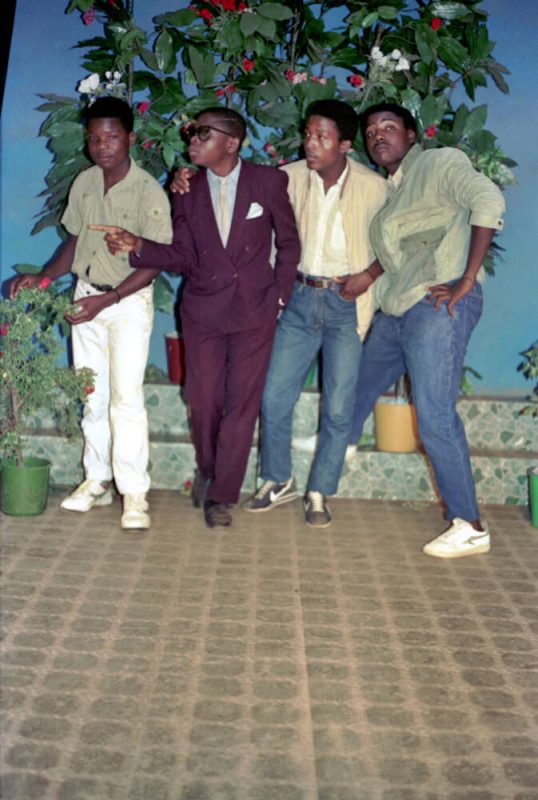

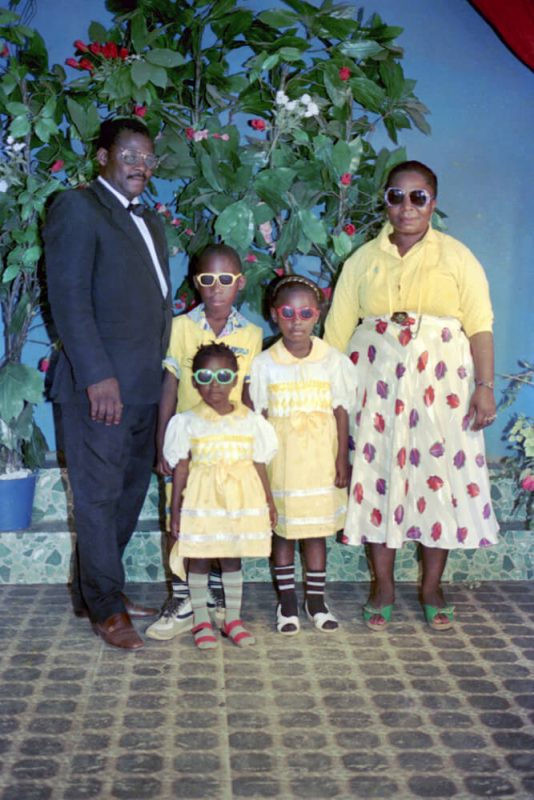

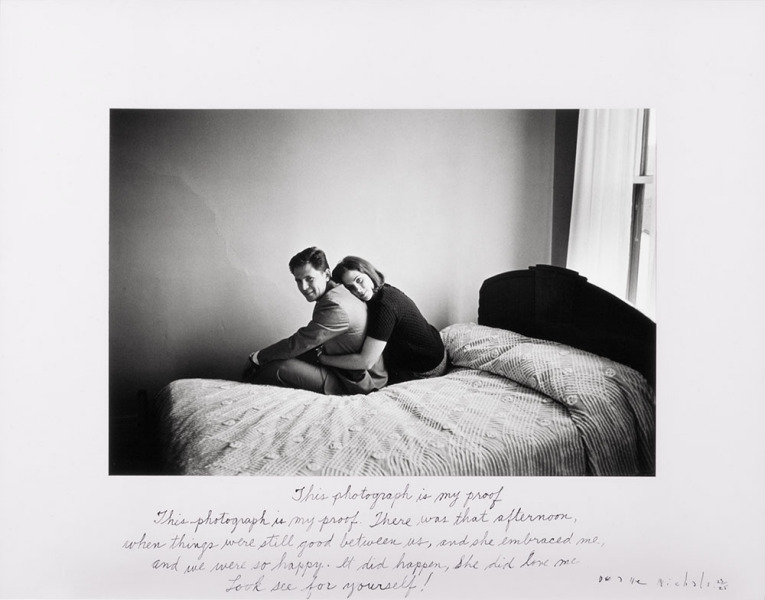

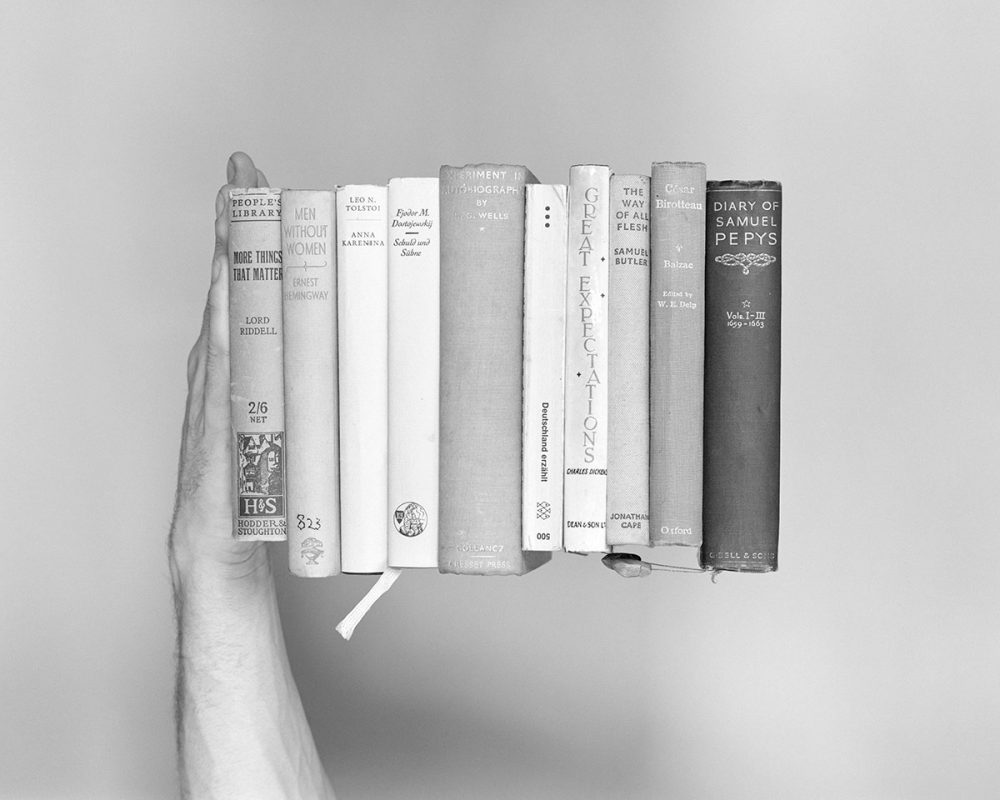

1985, his latest book, is designed by The Entente and published by Stanley/Barker, two individuals based in London, who have taken their time, in the most thoughtful way, to release two books simultaneously this year. This one is divided into two sections, comprising a short narrative prose text by Robert Walser – the Swiss modernist writer who died in 1956 – and in the other a series of intriguingly sequenced photographs taken by Henson. Walser’s text was originally published in 1982 in a collection of posthumously translated short stories, with an introduction by none other than Susan Sontag. Henson’s images were taken in 1985, both in Melbourne, Australia and Egypt.

Contrary to the dizzying curatorial language used to describe Henson’s work in 2006, the first pages of this book offer an altogether less disdainful proposition, in their turn to fiction. Such is the promise of a story.

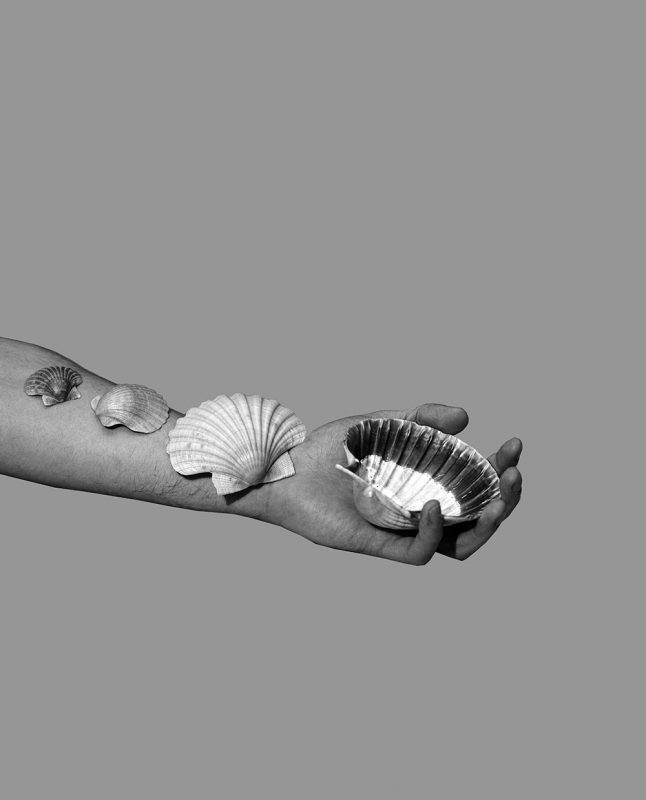

A captain, a gentleman and a young girl begin their upward rise in a hot air balloon. Various night effects are described by Walser in clear, physical description and the best kind of pleonastic turns of phrase. He also offers us the important contrast of plain language – in a ‘handful’, or something ‘splendid’, ‘subtle’ and ‘beautiful’. A nocturnal river below causes the girl to cry a little. She mourns its passing and throws a flower down to offer the water something symbolic as it passes by. Perhaps she celebrates its flowing power, but also her own tears, which are one in the same, in this gesture.

When the scene viewed from the balloon above moves into suburbia, or the city, the girl observes a burglary as people sleep. She smiles. Everyone is asleep apart from the robbers and those three characters in the balloon.

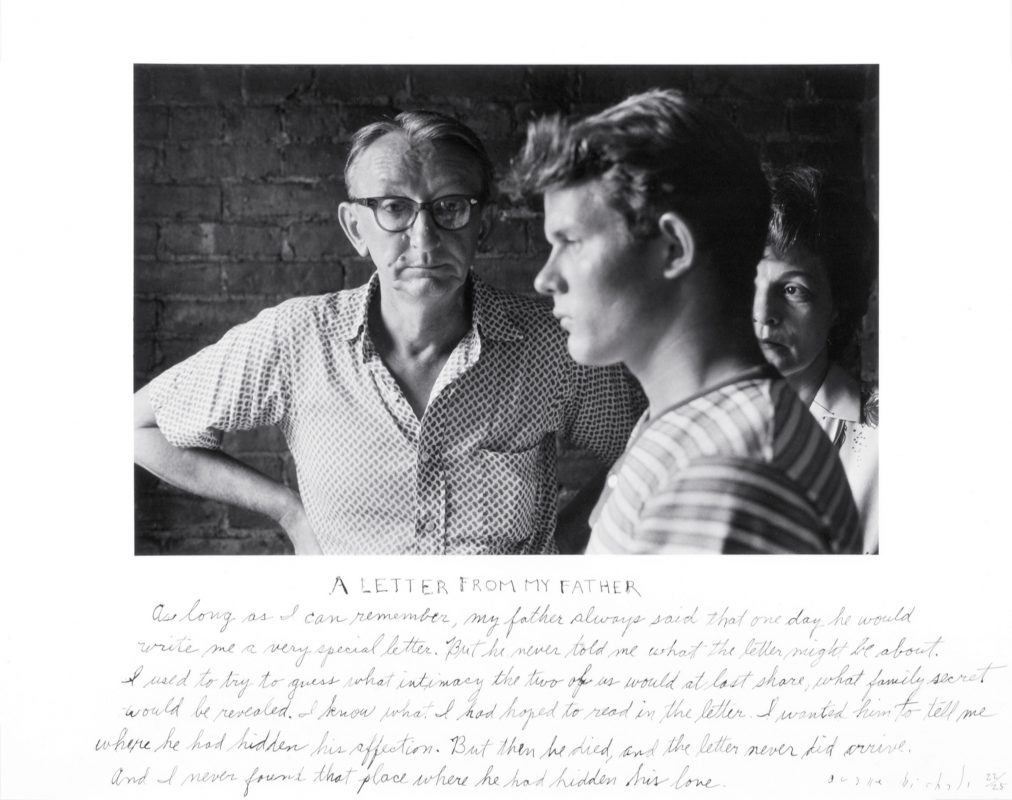

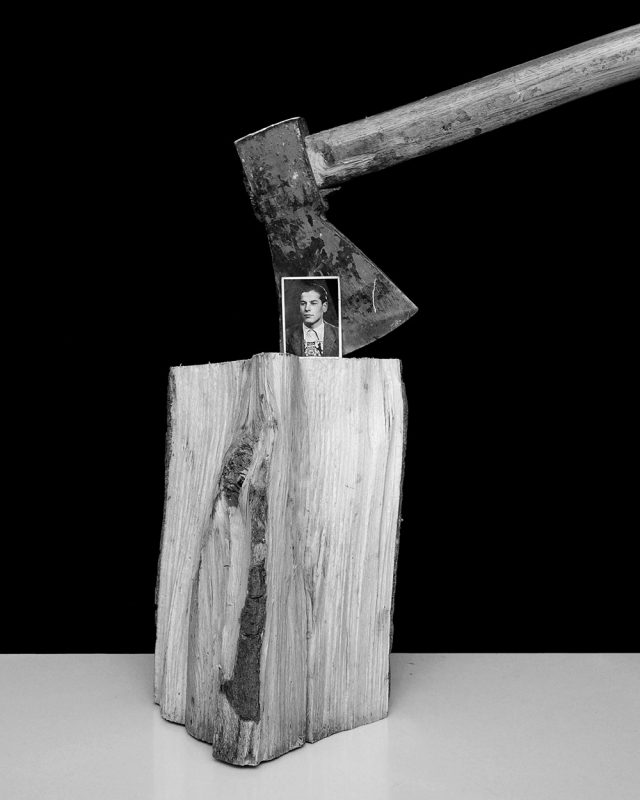

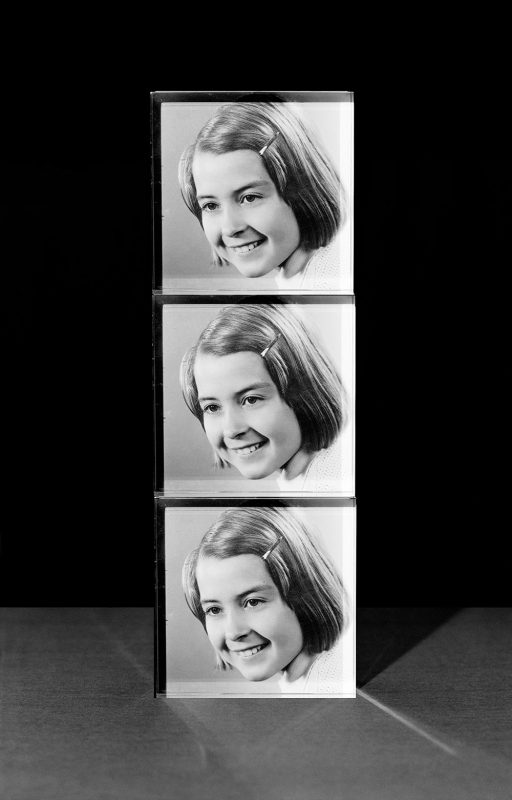

The story ends with daybreak. The reader, then, has been taken on a journey through night with three strangers. Before one views Henson’s photographs that follow the writing, an entire series of mental images are created through the text. We are therefore asked to consider one set of images, conjured through Walser’s writing, along with another in the form of Henson’s photographs that follow, something from the perspective of the sky and something from down below on the ground. This rich experience of many images at once, articulated from two perspectives, is what Henson excels at. Within his own images, and indeed the book as a whole, we are offered a stream of things paired together. Night and day, the sky and the ground, up and down. These movements are the pattern in which Henson works. Some things are paired logically, and others appear unrelated but nonetheless intuitive and compelling.

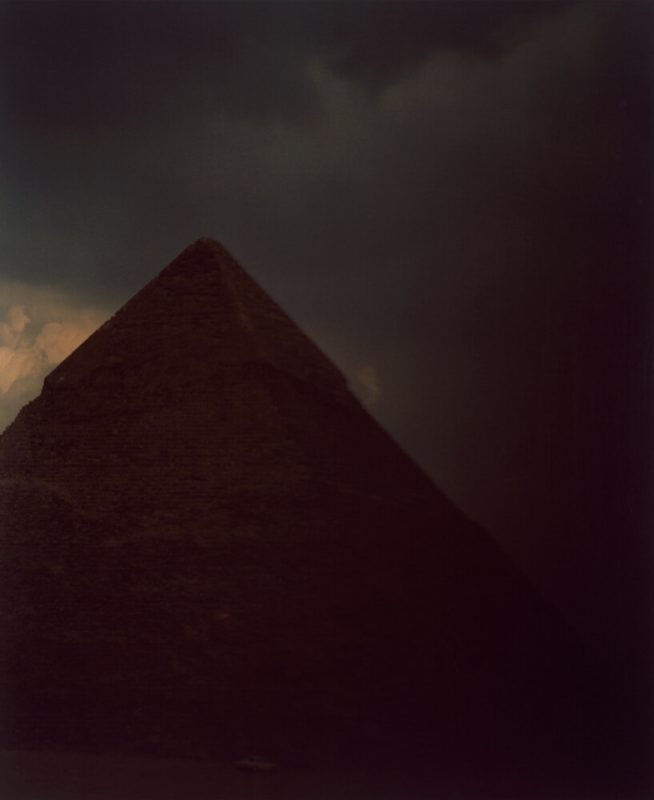

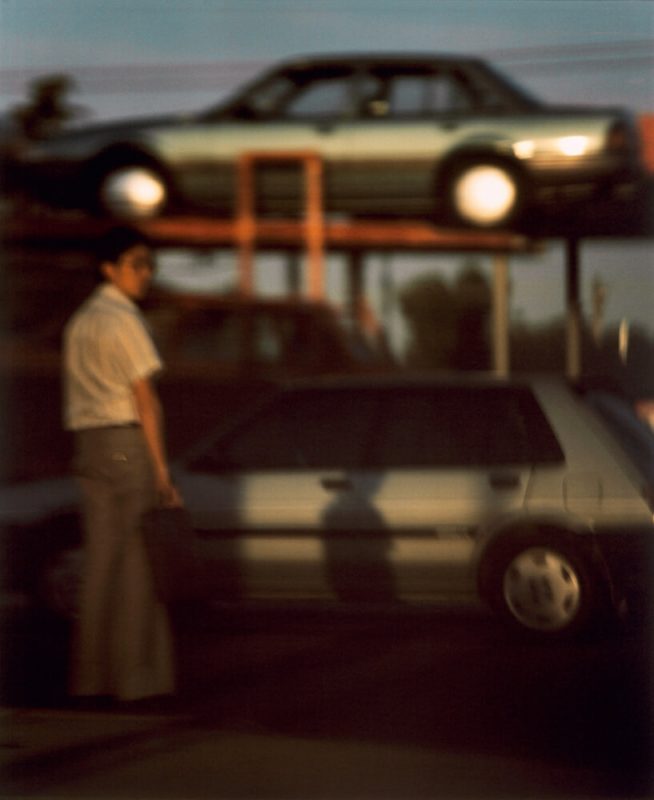

Three pages after Walser’s writing, a spread which depicts the vague shape of a pyramid on the left hand page, is pitted, on the opposite page, against two cars stacked on top of one another and a man in a short-sleeve shirt, glancing off to the right. Here we are looking at two pyramids: one shot in Egypt – in all its symbolic meaning reaching from the ground to the heavens – and one shot in the city of Melbourne, an metallic view of two cars either being transported for purchase, or to be salvaged or crushed, that much is unclear.

These relatable images speak of weight, but also of two types of historical symbolism that are vastly distinct. The pyramids in Egypt, in their geometric form, mimic the shape of the sun’s rays. We might understand Henson’s image of a pyramid, then, as a means to offer light where there is none. But a pyramid, photographed in darkness as Henson does, paradoxically withholds any reflection of the light that might emanate from this so-called primordial mound. At its most metaphorical level, Henson’s pyramid reduces the grand stature of the Egyptian sun god Ra to a bleak triangle cowering in shadow. And in a more everyday contrast, the opposite almost-pyramidal roof of a car is reduced to a simple, inert object of industrialisation.

Whatever one reads into Henson’s pairing of disparate scenes, there is certainly some process at work which seeks to compare Ancient Egyptian architecture and its referents, to that of 1980s Melbourne. Like the girl who mourns the passing of a river and then strangely smiles at the burgling of a house, Henson too responds in an unexpected manner by way of his photographic observations of two distant and antithetic cultures. Perhaps 1985 should be read as a work in writing. Not one that gestures towards twilight as a metaphor for photography’s own philosophical relationship to light, nor some grand description of the supernatural or the contemporary sublime, but instead simply of the sort of effect that occurs when the things we normally see lit, are reduced into a sort of tenebrous poetry of cultural contradictions and symbolic juxtapositions. ♦

All images courtesy of Stanley/Barker. © Bill Henson

—

Daniel C. Blight is a writer based in London. He is co-editor of Loose Associations, a periodical on image culture published by The Photographers’ Gallery; visiting tutor in the department of Critical & Historical Studies, Royal College of Art and lecturer in photography at the University of Brighton.