Matt Lipps

Library

Essay by Chris Littlewood

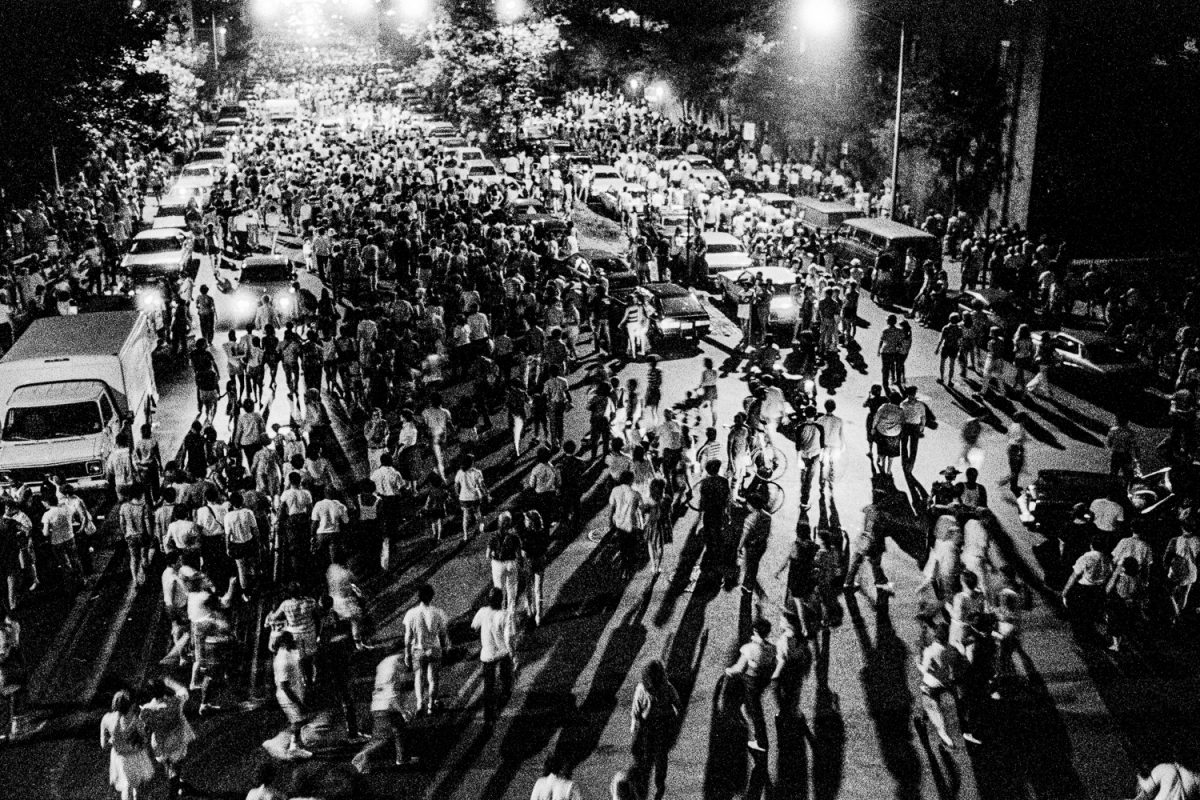

Starting in 1970, Life-Time magazine published images from their immense archive of mass-media and fine art photographs in a series titled Library of Photography. It was a 17-volume hardback edition delivered to people’s homes at a time when analogue SLR cameras were sweeping through America. After more than a century confined to exclusivity, across the country Polaroids were being pulled, family albums built. This was the moment when automatic photography became part of the mass consumer market. Demonstrative and diagrammatic, the Library of Photography began by showing depictions of darkroom equipment and cross-sections of camera bodies. From the instructional to the iconic, the series was illustrated with gravure reproductions of work by celebrated photographers, including Irving Penn and Bill Brandt. One volume was dedicated to some of the most recognised photojournalism of the time while chapters ranged from techniques to genres to the conservation of photographs, this was an all inclusive visual aide – everything you could possibly need to know about photography.

Matt Lipps is a California-based artist known for his astute examination of pre-digital photographic material. By way of dissecting, mounting, reassembling and lighting, Lipps’ ornamentation of found photographs delivers the images out of antiquity into a meaningful present. By bringing together the amateur with the professional, the procedural with the artistic, Lipps’ approach is nothing short of democratic. Together with overtly stylised coloured backdrops or lighting gels, the overall effect is at once retro and contemporary. They are hybrid images – visual seesaws between past and present – that places Lipps’ work within a critical mass of predominantly American artists engaging with a post-Photoshop, post-internet image culture.

“We live in a photographic mind-set, creating memories for the future,” Matt Lipps has said. And with it, Western society now carries a camera in its pocket. That an unprecedented number of photographs are being produced daily is not in doubt. We are visually saturated and photographically dependent. Increasingly people experience life through the lens of social media platforms, where digital photography becomes less a tool of candid documentation and more a constructed reality. We manufacture moments that look like photographs that will become memories we will treasure. Concurrently, ‘art photography’ is experiencing a surge in techniques that seek to dissolve observed reality with digitally generated imagery, studio assemblages and appropriated material with sculptural installations. ‘Constructed photography’ has become the term of the day.

In his essay from the current issue of frieze magazine, entitled Construction Sight Aaron Schuman places Matt Lipps alongside Daniel Gordon, Noemie Goudal, Chris Wiley, Hannah Whitaker, Lorenzo Vitturi, Sara Cwynar and Asger Carlsen as the frontrunners of this generation. Linked by their focus on photographic form over informational content, these artists utilise photography as both a technical endeavour and a physical medium. It is the “scaffolding of the photographic medium [that becomes} explicit and intricate”. Lorenzo Durantini writes of a similar group in his essay Tool Objects: “These artists allow us to witness the evacuation and fragmentation of the object and the emergence of the tool as the primary focus of this new hybrid practice” in an article from The British Journal of Photography in 2012. The same year Durantini curated Brush it in at Flowers Gallery. Taking its title from a colloquial expression associated with the act of digital manipulation using Adobe Photoshop, the group exhibition was an assembly of works – including photo-sculptures – that engaged with the pictorial tension between virtual editing and physical intervention. There have been a handful of exhibitions in this vein, notably Foam Museum’s Under Construction – New Positions in American Photography.

It is easy to see why the photographic convention of studio-based still life has been adopted by many of these artists. It has long been associated with a heightened sense of looking and perceiving. It is also deployed as the primary language in the advertising world’s relentless campaign to sell goods. As Durantini states: “The inevitable disappointment of mass-produced commodities has created a sort of haptic half-life where the image produces more pleasure than the object itself.” This has created a fertile borderland between representation and experience, where artists are able to explore and enact revenge. No longer relevant as a genre in its own right, the devices associated with still life have all but been consumed by ‘constructed photography’. In many ways the role of the early travelling photographer helped to free artists from the confines of the studio. Now it seems the reverse is true. The studio practitioner is now freed through their ability to exert full creative control, to roam across modes of practice with seemingly little regard for tradition.

Alongside still life, there has been much talk about appropriation in a critical sense. It’s possible that Matt Lipps and others represent a kind of optimistic appropriation where the artist is partly naive. The word ‘curator’ has now become a ubiquitous term synonymous with anyone able to edit, sequence and share images. Blogs along with websites like Instagram and Pinterest enable users to not only produce unique content, but to intersperse it with existing and often anonymous material. It comes as little surprise that artists too are drawn towards this curatorial impulse.

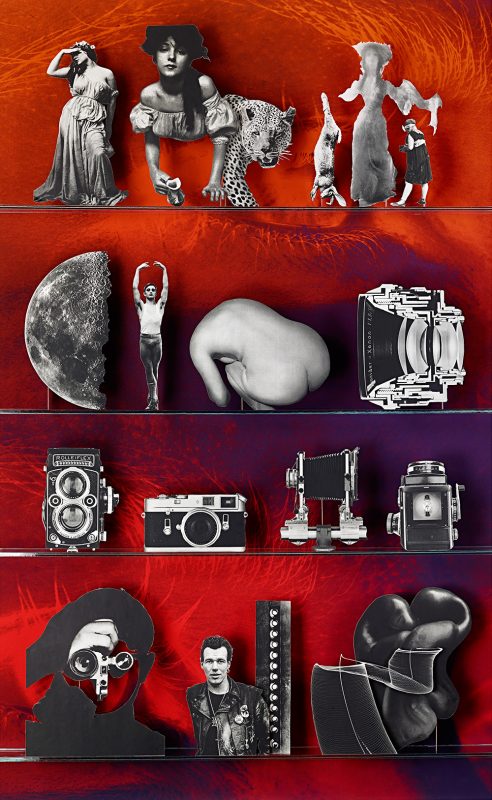

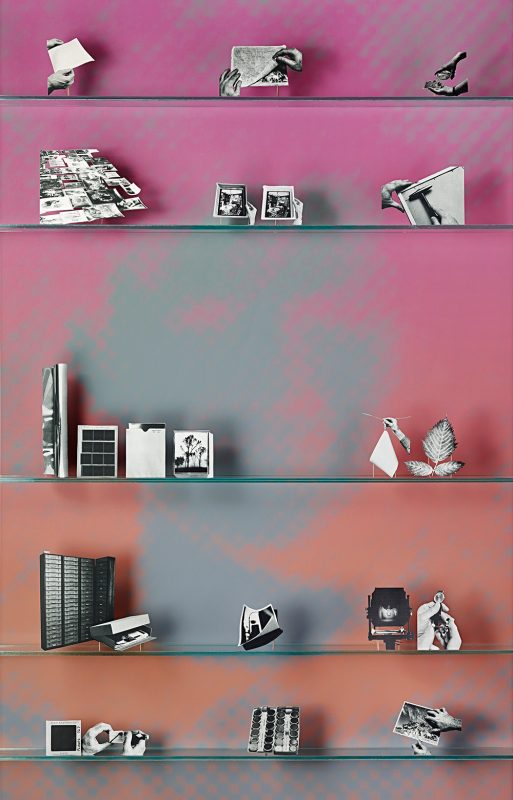

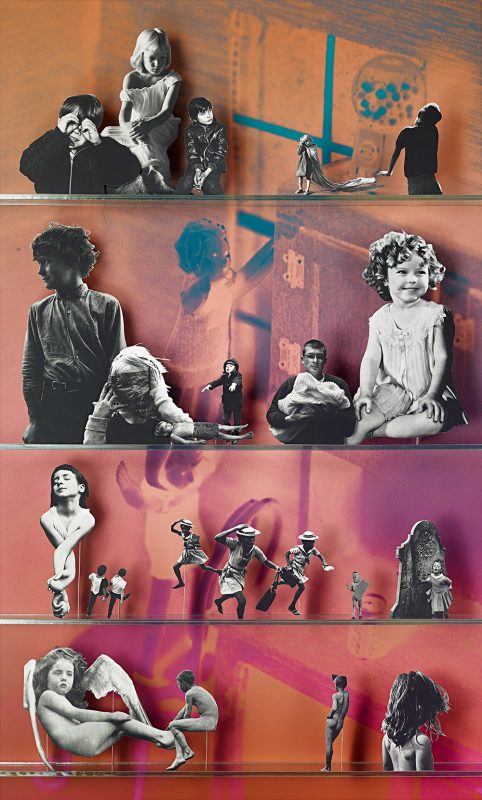

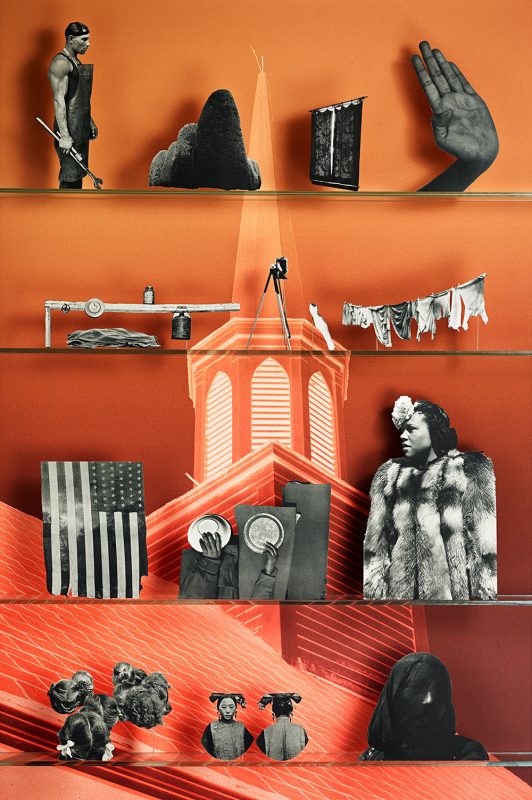

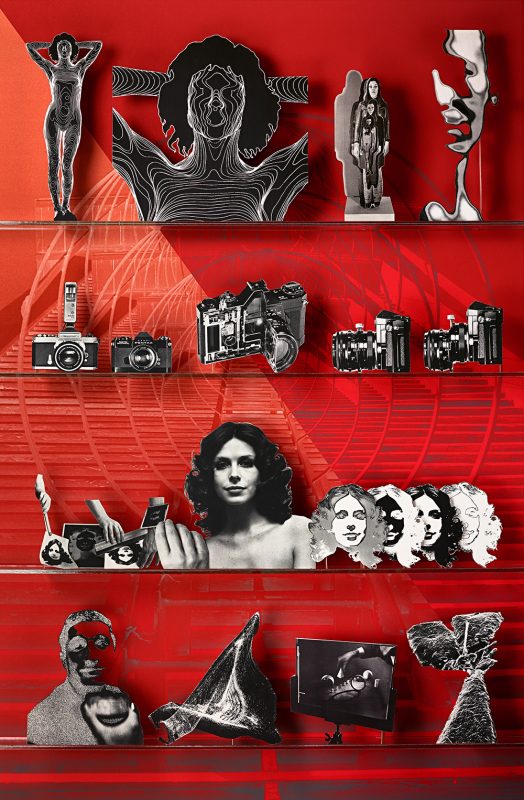

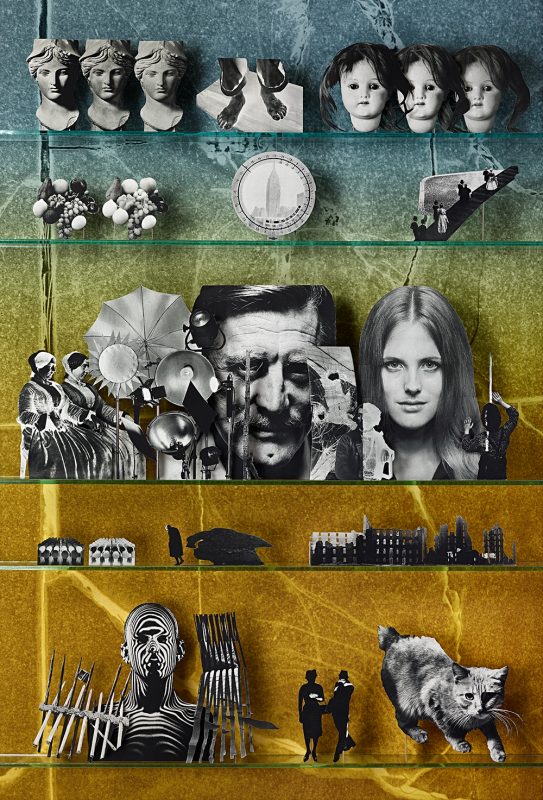

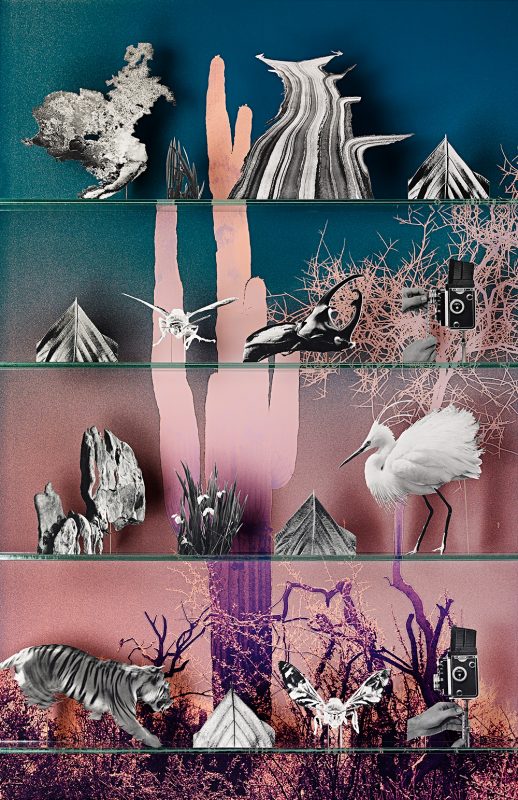

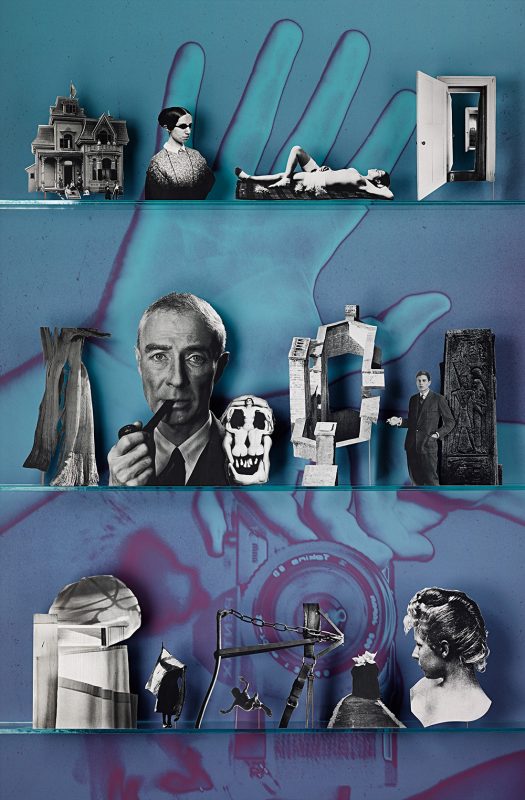

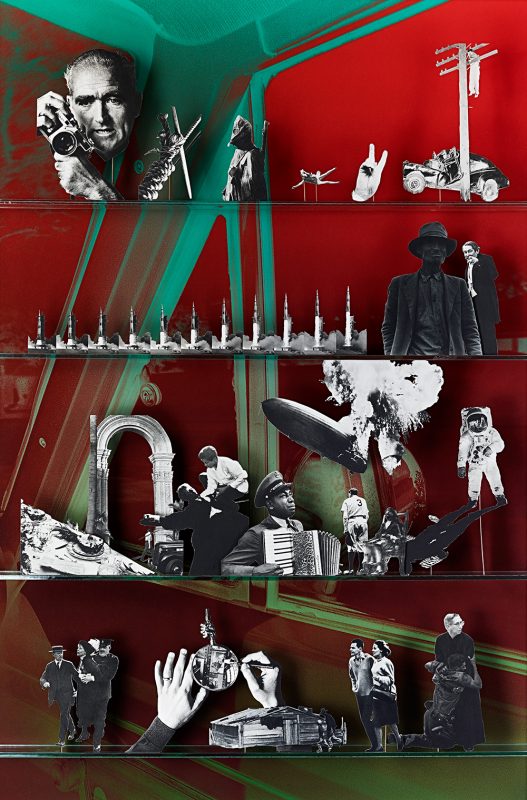

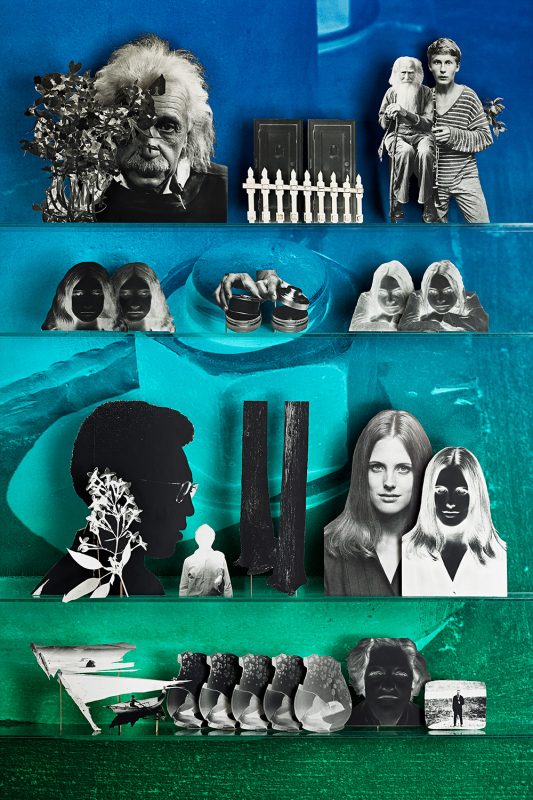

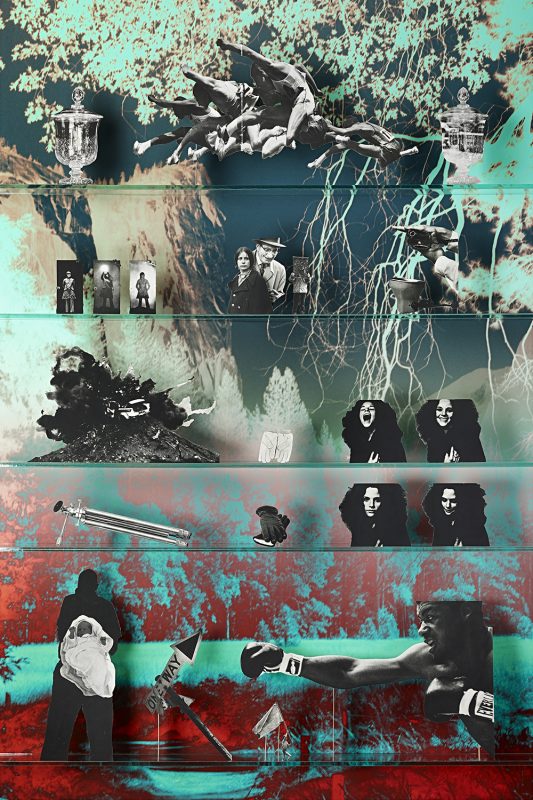

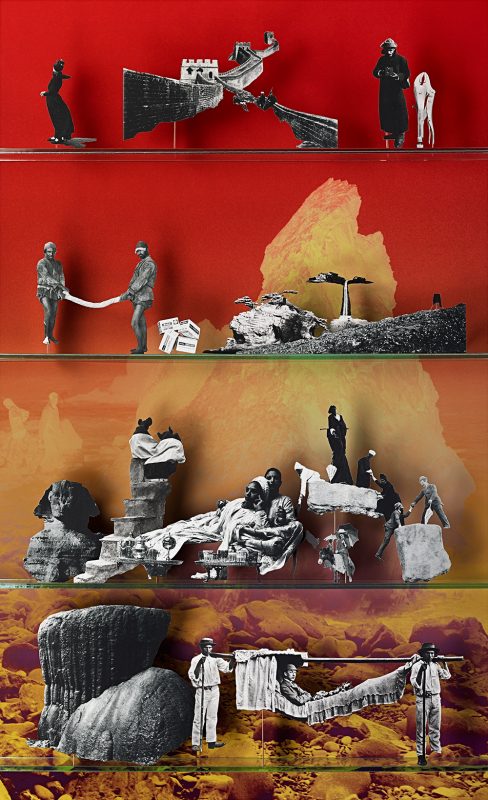

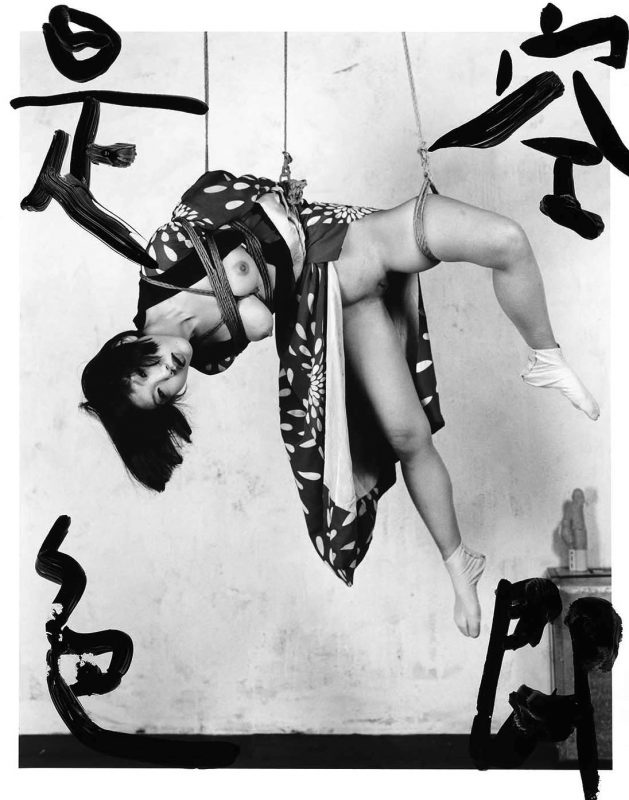

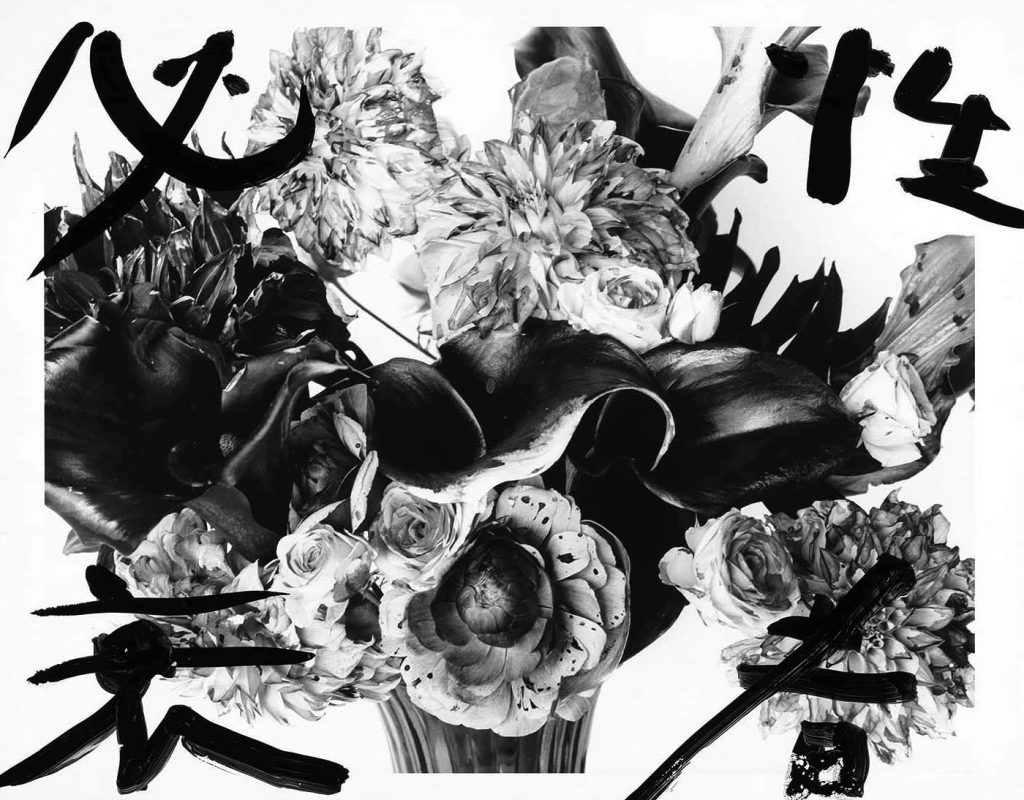

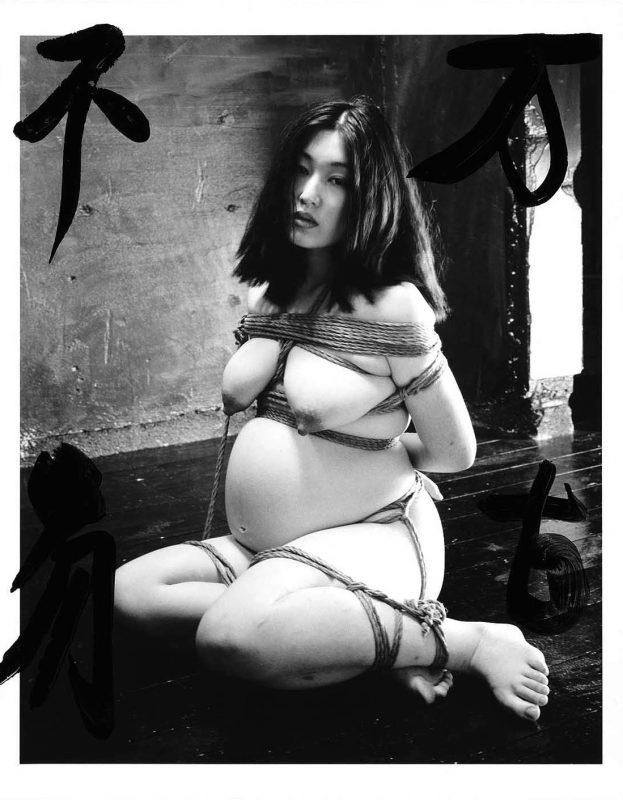

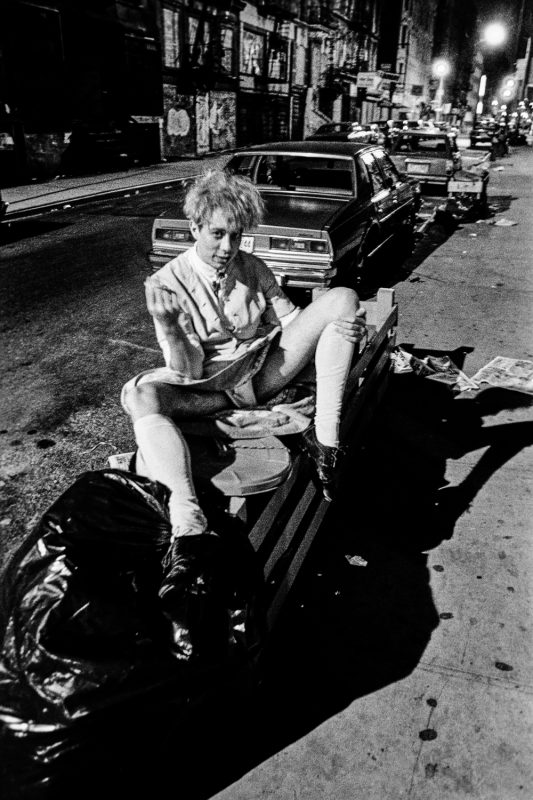

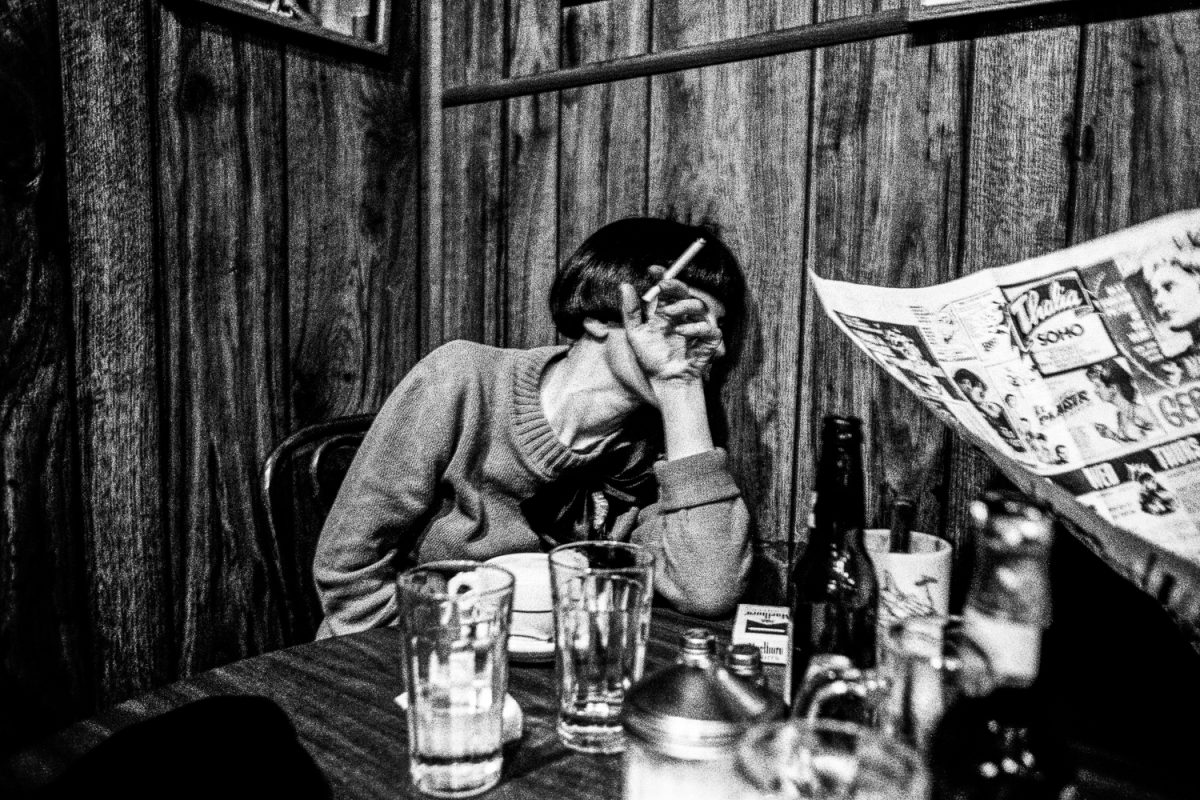

Operating as individual case-histories, Matt Lipps’ Library presents us with the artist’s edits as single pictorial planes; an overview of what a particular area of photography might show if viewed all at once. Playful yet unnerving, bizarre juxtapositions of subjects and scale jolt the viewer out of a traditional reading. Images are blended together in such a way that their individual histories and scale are not important. By freeing images from a rigid and linear context, Lipps’ grid-like compositions display content more akin to a Google image search. By referencing the layout of bookshelves, the viewer oscillates between the dimensions of screen-based and print-based media.

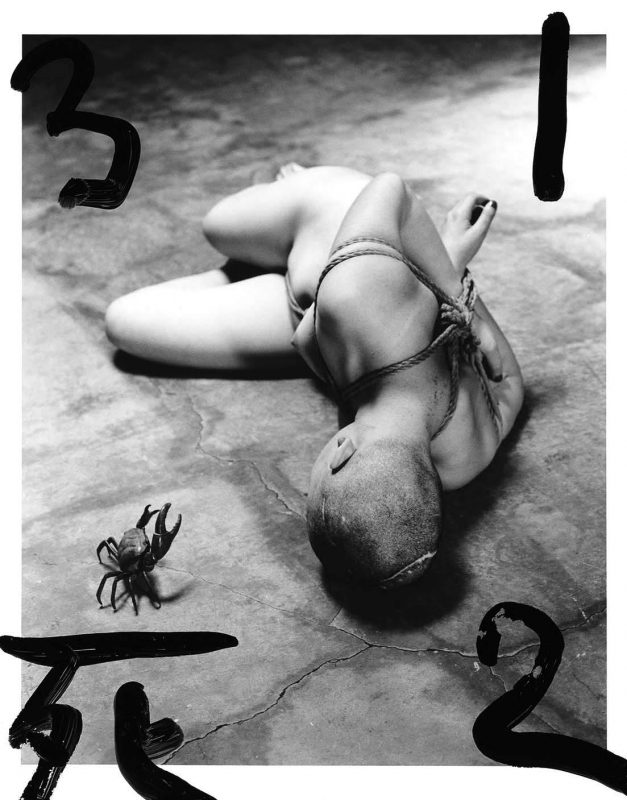

Library comprises of 17 works based on each of the original Time-Life volumes. Lipps begins by cutting out images and staging them like theatre props on glass shelves. Likened to cabinets of curiosities, the tableaux also resemble fossil samples in their pseudo-scientific means of display. Lipps creates static scenes for the camera, fabricated in order to be photographed from a specific angle, with specific lighting at a specific time. Through striking economy, Lipps breathes life into each cast of the outsized characters and oddities. Polarised with seductive colours, the backdrops are scans made from the artist’s own archive of early 35mm negatives. Although Lipps himself did not learn photography from the Time-Life publications, he was educated in a similar manner. Ignoring the advice he now offers students, Lipps goes about breaking every unwritten rule of Photoshop – deliberately oversaturating and applying gimmicky filters. By combining the personal with the canonised, the compositional unity conjures an objecthood that is wholly surreal. Library contains shapes that the viewer apprehends, but cannot necessarily perceive in his/her spatial environment.

When photography replaced painting as the instrument of factual representation, it allowed painting to go through a process of self-exploration where formal qualities such as composition or colour became subjects worthy of artistic endeavour alone. As computer generated imagery replaces photography, perhaps the medium of photography is also experiencing a similar process of introspection. In the work Photographers, 2013 doors open to unknown places, chains, artefacts and memento mori cover an obscured self-portrait of Lipps. A reflection of the artist’s camera stares back and suddenly the observer becomes the observed. Superimposed in the centre sits Salvador Dali’s In Voluptas Mors, a form which blends beauty with death. Six female nudes are materialised as a pair of hollow eyes, jagged teeth and a skull. A giant cyan hand emerges from behind the trophy cabinet of moribund misfits as if to wave them off to an impending doom. Part Requiem to an analogue craft, part evolution, Matt Lipps’ Library may come to represent a key moment in photography’s new found formalism. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Matt Lipps

—

Chris Littlewood is a curator and writer based in London, who currently works as the Photography Director at Flowers Gallery. The programme at Flowers has included exhibitions by represented photographers Boomoon, Edward Burtynsky, Nadav Kander, Mona Kuhn, Robert Polidori, Simon Roberts and Michael Wolf.