Vittorio Mortarotti

The First Day of Good Weather

Book review by Natasha Christia

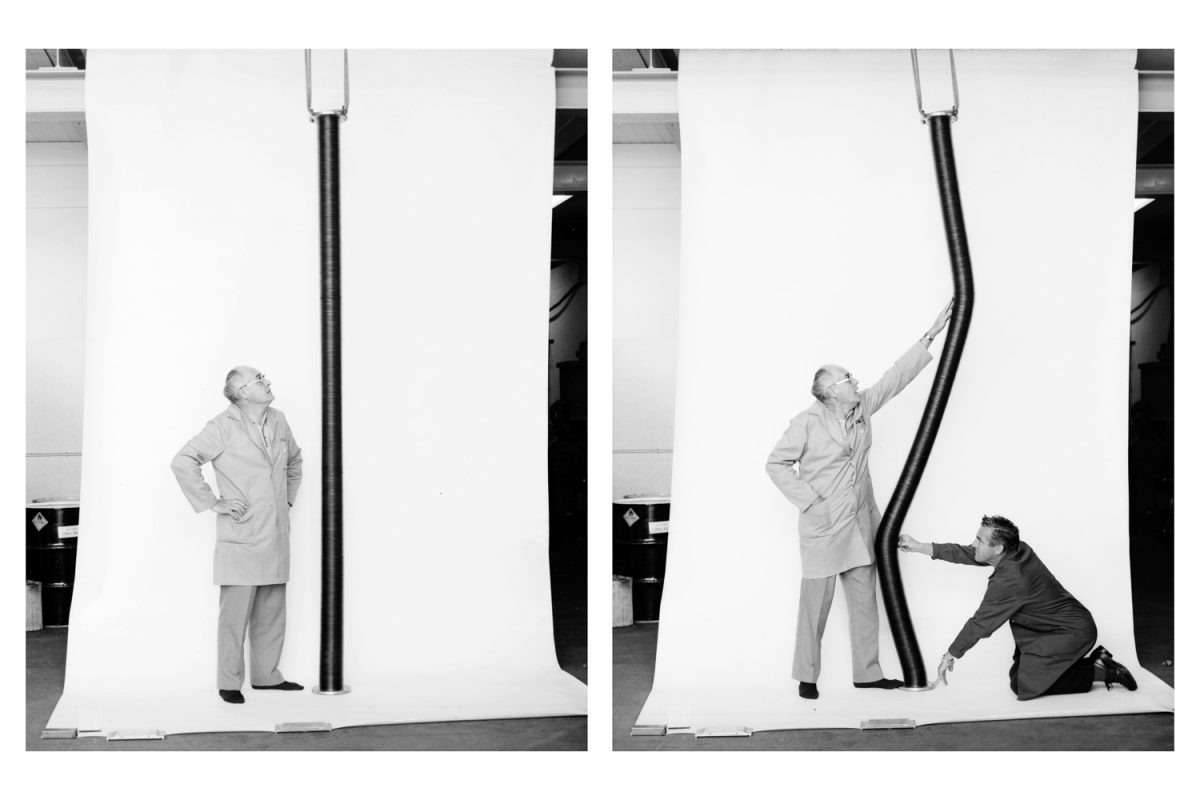

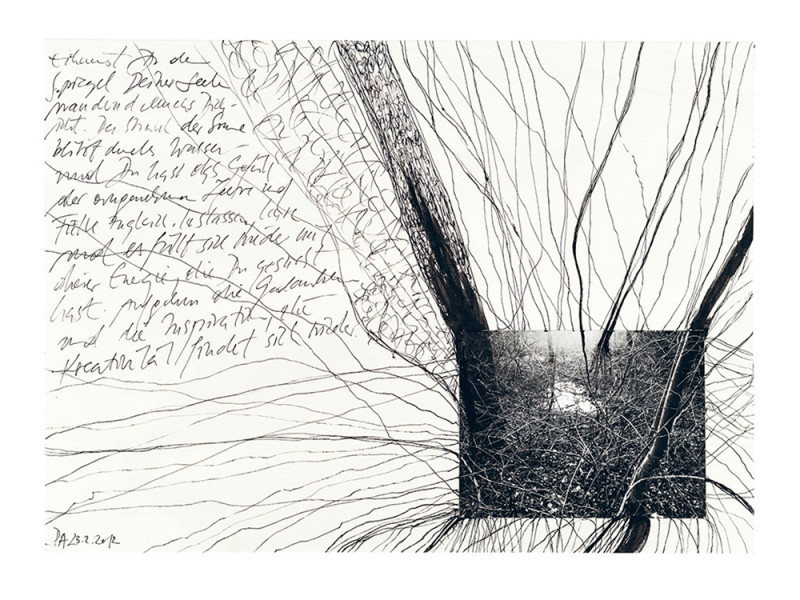

Vittorio Mortarotti’s The First Day of Good Weather feels like one of those books that asks you to go back to it again and again. It is multi-layered and cryptic in tenor, and its sequence is constructed with sophisticated albeit uncanny couplings of seemingly disparate elements. It is a style that can be seen in other Skinnerboox publications, such as Alessandro Calabrese’s superb Die Deutsche Punkinvasion, where the juxtaposition of close ups of junkyard cars with archival pictures of punk revolts produces a chain of striking and effective connotations.

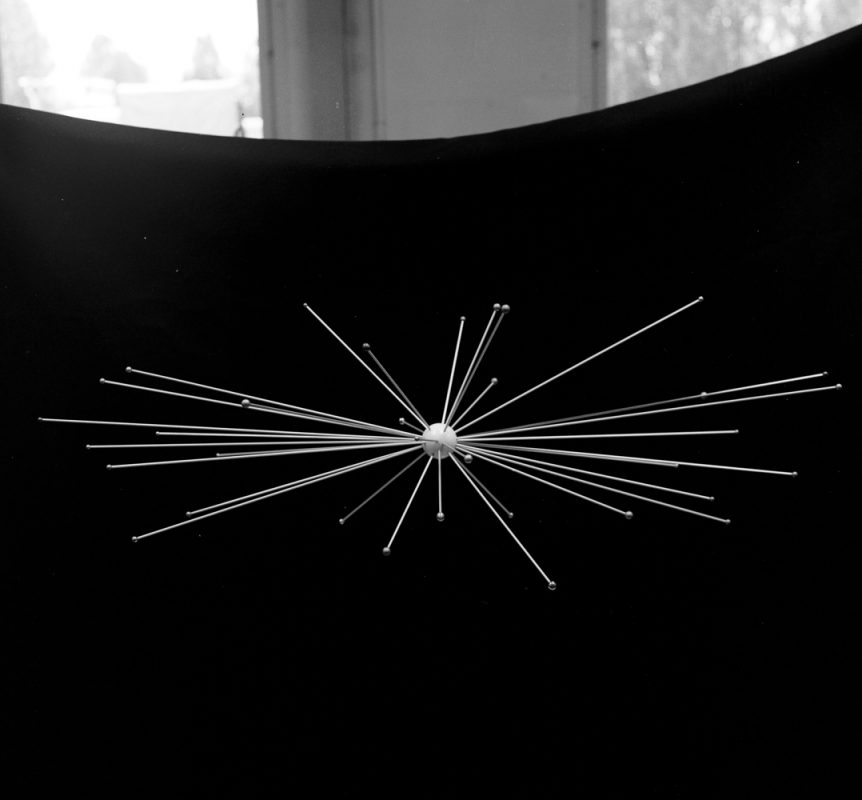

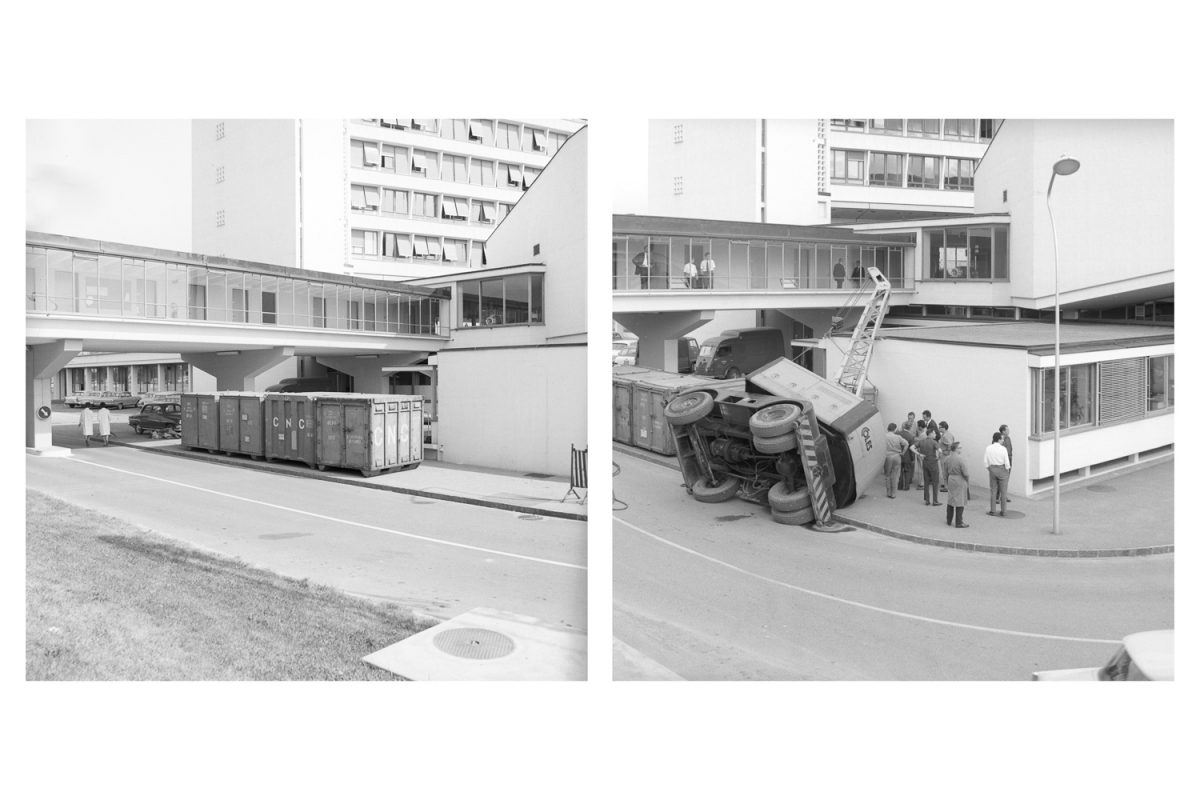

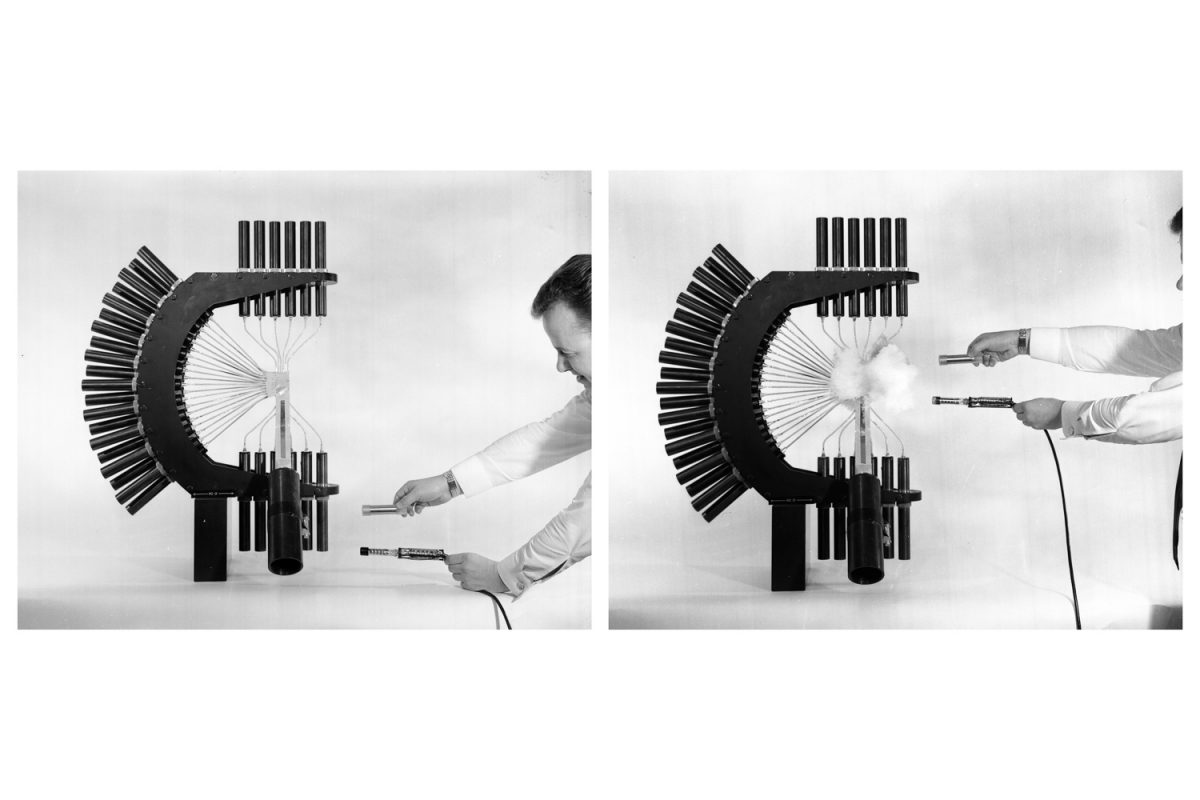

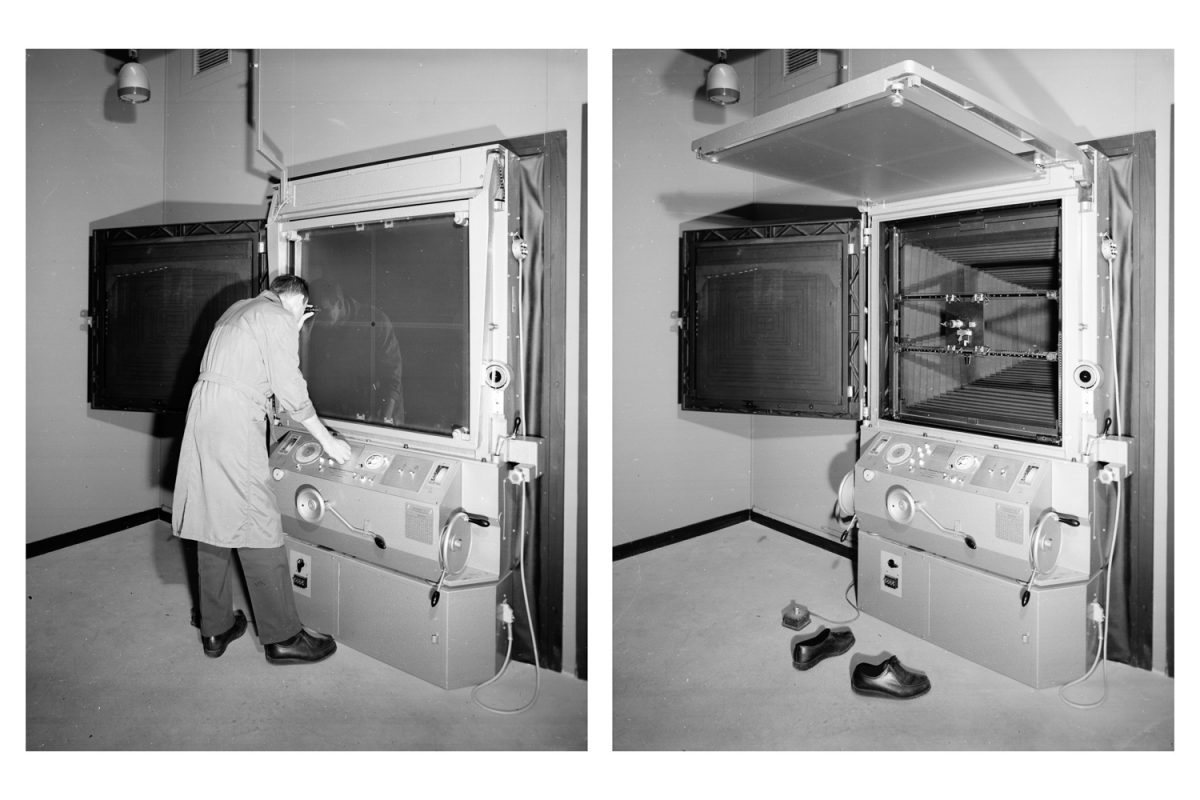

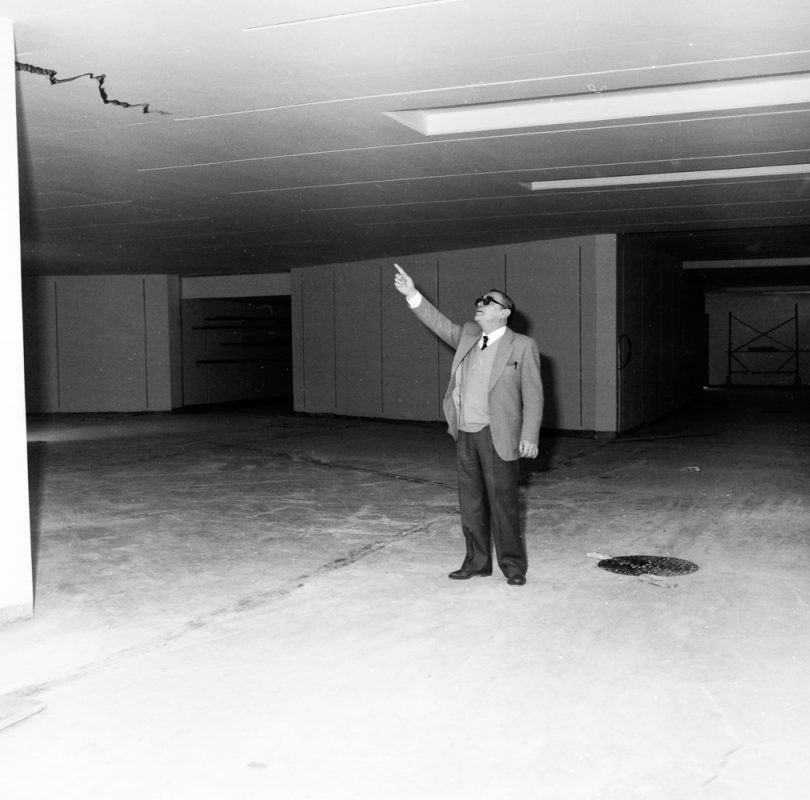

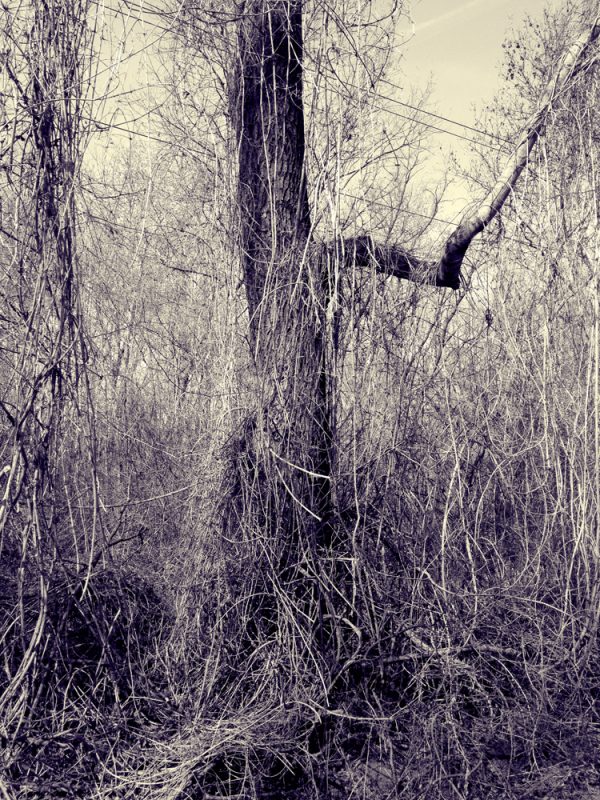

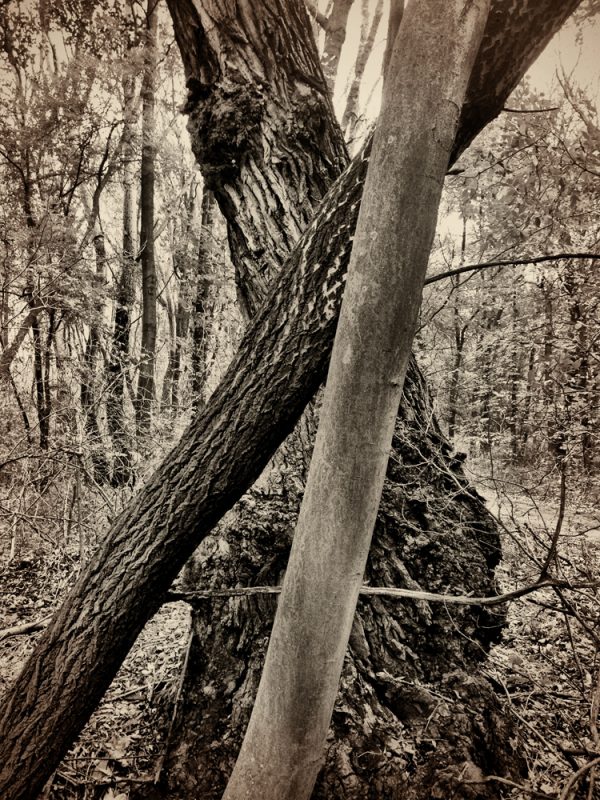

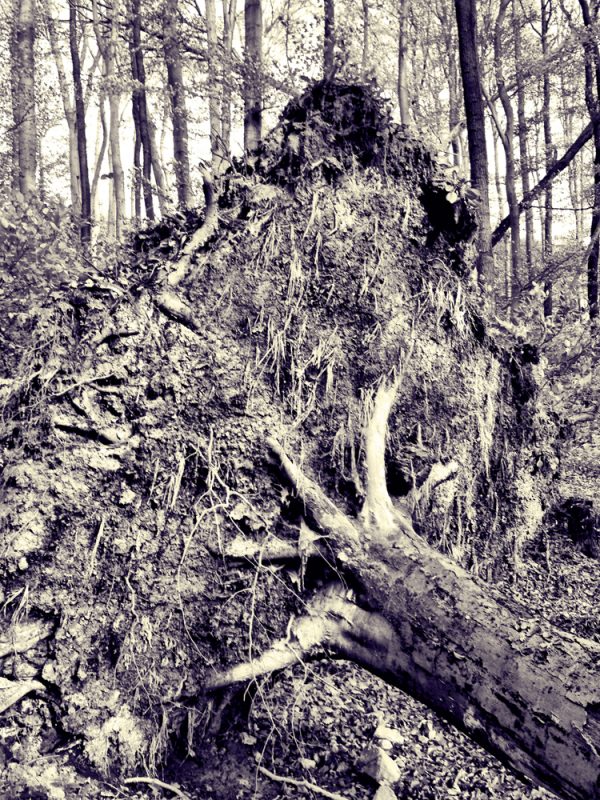

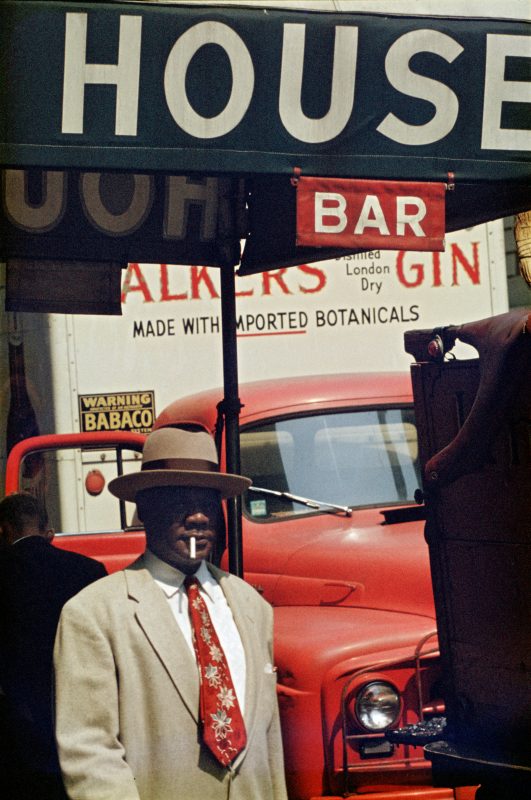

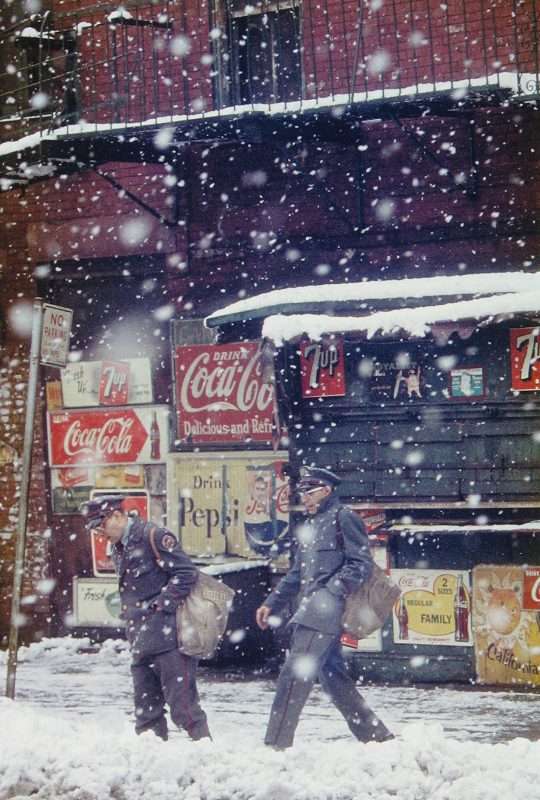

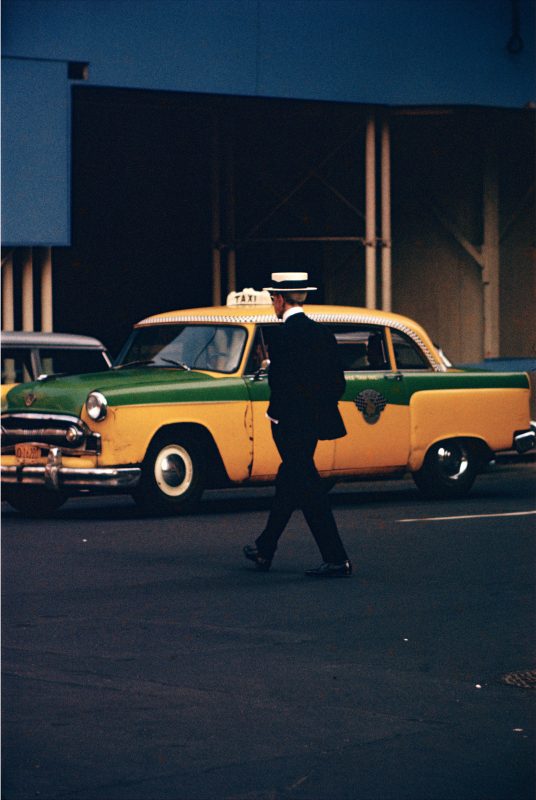

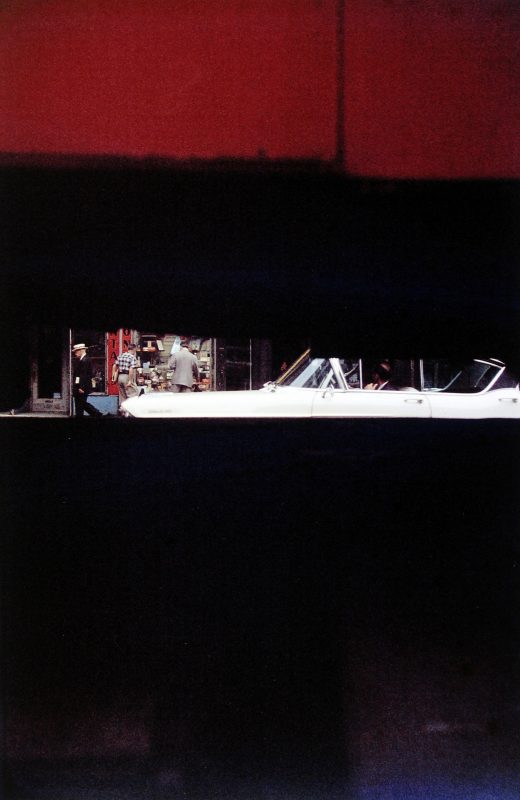

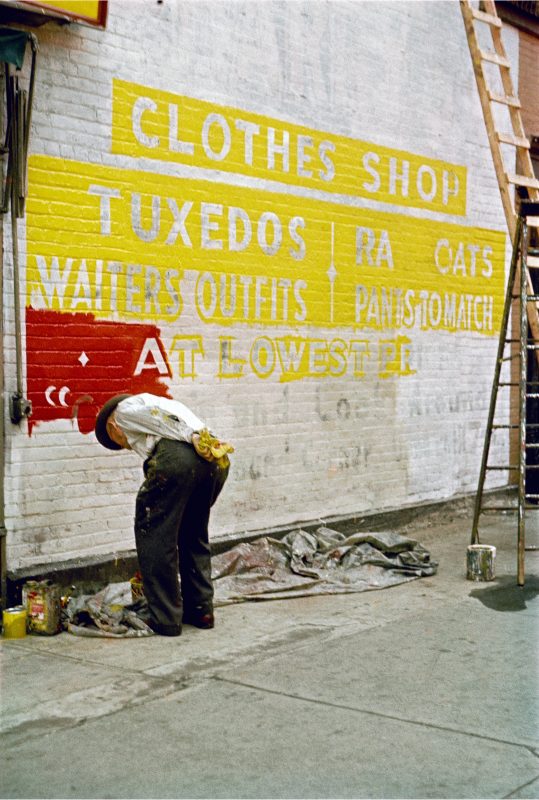

Impelled by a similar penchant, Mortarotti’s narrative takes me through a misty topography of devastation, melancholy and resignation. There is a bluish undertone to the book, a sort of mute score reverberating in the depths of an ocean. Night and day alternate indifferently in perennial circles of rising tides; views of semi-demolished houses, cracked cement blocks and smashed cars are paired up with flashy portraits of drained individuals and tormented night bar affairs. And yet, I can tell that beneath this rough, silent mood is a winding stream of emotions, a lust to hang on to life. This collision of distinctive visual and emotional registers within a low-spirited, obscure and industrialised environment turns into both a graphic and literal incarnation of an attempt to get access to a secret, to recollect its traces, to grasp how life can be after everything has been smashed into a million pieces.

Then, all of a sudden, in the middle of the book, a text has been inserted, dating back to May 1999. It is a letter written in French by a Japanese woman named Kaori. It is addressed to a man. This letter complicates the story. It makes it clear that there is much more in here – something deep, personal and intimate.

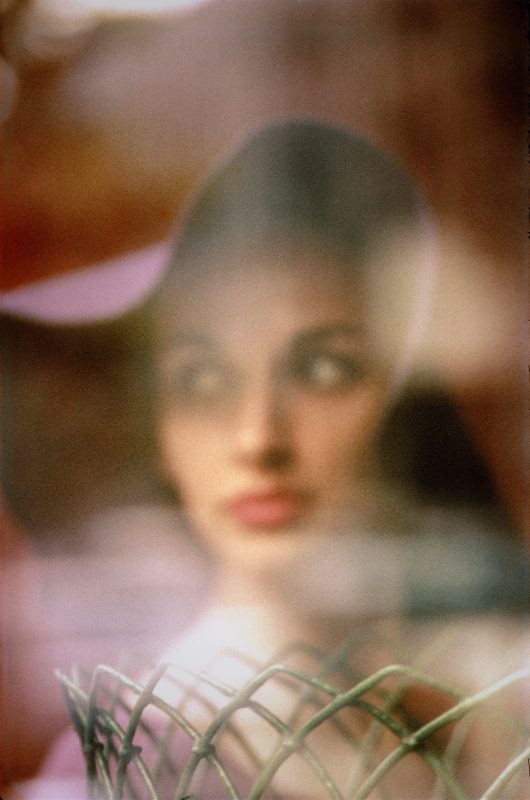

In the pages that follow, the story recovers its visual pace. But while Mortarotti’s gaze keeps safeguarding its distance from dramatic exasperations, it unleashes an unsettlingly emotional, almost existential register that drives me away from the letter and away from words.

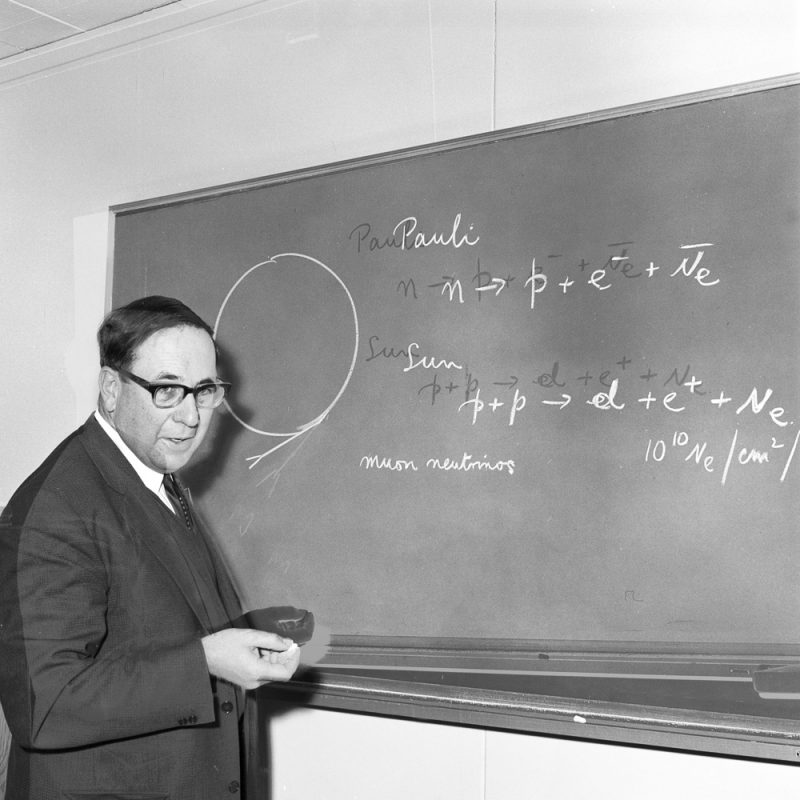

In the colophon I read that the book brings together three unconnected moments: the fall of the atomic bomb over Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, the death of Mortarotti’s own father and teen-aged brother in a car accident on 8-9 July 1999, and the terrible earthquake and Tsunami that shook Japan in March 2011. All moments of historical relevancy; all massive, unexpected, unprecedented and utterly devastating in their after-effects.

In the wake of this data assemblage everything falls into place. Death appears here in capital letters and History intermingles with personal traumas. The locations shown in the book recover their names: Fukushima, Tokyo, Hiroshima … And as for the letter, it forms part of the correspondence between Mortarotti’s brother and Kaori, his Japanese girlfriend who kept on writing and sending postcards for months after the accident. Tracking this pack of letters and looking for Kaori fifteen years later became, for Mortarotti, a pretext to visit Fukushima and the area hit by the Tsunami in a cathartic search for what might have been in the aftermath of stories of loss other than his own.

I am aware now of many key elements of the story. Too many, perhaps, in the eyes of the purists still inhabiting our photographic community. Photographic purism would dismiss the book I hold in my hands as too dependent on words. It would dictate that sequence must speak for itself, that we do not need illuminating words; when these are needed, they say, it is because the images do not work for themselves.

But curiously, The First Day of Good Weather feels relevant precisely because it breaks these rules with its contaminated and versatile mood. Removing the limitations of visual storytelling or photobook-making is an option in its own right. But it cannot become axiomatic. It does not and should not exclude other options. As Jean-Luc Godard said, “It’s not where you take things from – it’s where you take them to”.

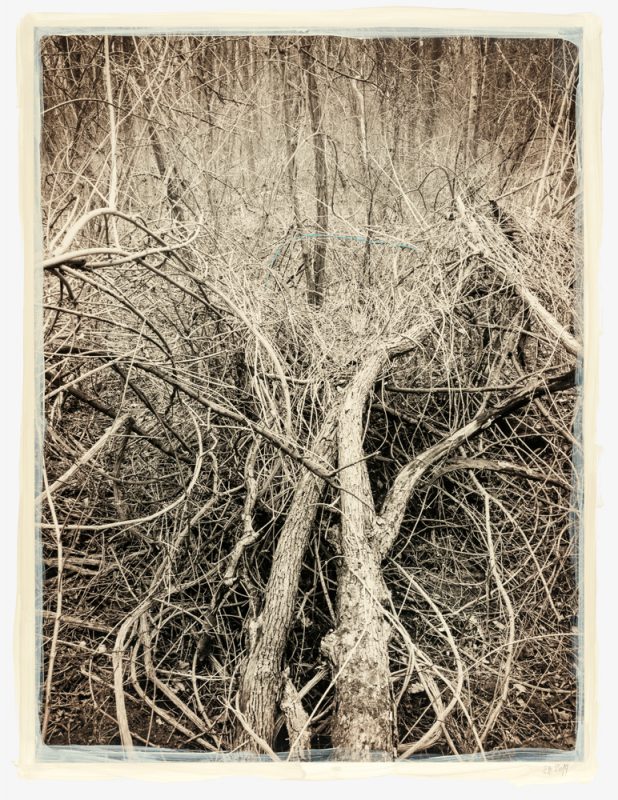

The First Day of Good Weather is a hybrid photobook in every sense of the word. By expanding its branches to apparently irrelevant storylines, its narrative adopts an elliptical style akin to cinema and literature. At the same time, it masterfully combines and balances the documentary, diaristic and conceptual modes with a marked preference for a “slow” inception of reality and its facts. The links between the photographer’s personal tragedy and Japan’s collective trauma play out the universal mechanisms of coping with grief and of moving on after experiencing a dramatic event. Mortarotti manages to tackle the delicate and private sphere of mourning without falling into cliché or an excess of autobiographical references. What’s more, he brings Japan to the foreground in an unpretentious and neutral way. It would have been easy to let it take up the entire frame for the umpteenth time, but he does not. He avoids temptation.

How can we approach an alien space? How can we cope with death and its remnants? How can we overcome it? The components of Mortarotti’s story are tied together by the intuitive assumption that the bits and pieces of our immense world are interconnected. During most of his journey around Japan, we feel attached to the ground. Then the bird’s-eye view in the small postcard pictures of skyscrapers and the portrait of a woman (Kaori, in the present) against the window and the blue sky introduce a soft, airy element – a parallel dimension to the journey. There is a climax of sensations that reinforces an awareness of the randomness of cosmic events – a volatile lightness, horrendous in many ways, as the title of the project suggests. The first day of good weather was the day life stopped in Hiroshima. “The first day of good weather” was the order issued by President Truman to drop the atomic bomb on Japan. On 6 August 1945, it was raining over the other targets. It was sunny over Hiroshima.

We are used to conceiving of books – not merely photobooks – as static objects, but perhaps it would be useful to consider that they might not be. Books, after all, are elastic condensers of time. They exist in time; they grow with us. They stand for a sort of synaesthetic experience where we, the reader, have to contribute our imagination and intuition to fill in the gaps.

So I let myself drift into The First Day of Good Weather. I let myself add to its sequenced layers of experience emanating from my personal debris. Experience that adds more lines to the story as if it were an unfinished novel. I catch myself going back and forth. Especially backwards in a futile hope that this movement could restore something of the past. Rather than revoking the trauma, I seek to accommodate it in the present. I catch myself returning to The First Day of Good Weather for there is something in it that persistently resonates in my mind: an intense, sustained and profound force that replenishes its argument and makes me see it anew. ♦

All images courtesy of Skinnerboox. © Vittorio Mortarotti

—

Natasha Christia is an independent writer, curator and educator based in Barcelona. She was recently the guest editor at the Read or Die publishing fair in Barcelona during November 2015. She has also been appointed as curator of the upcoming edition of DocField Documentary Photography Festival, taking place during May and July 2016, entitled Europe: Lost in Translation.