Peter Fraser

Mathematics

Book review by Jeremy Millar

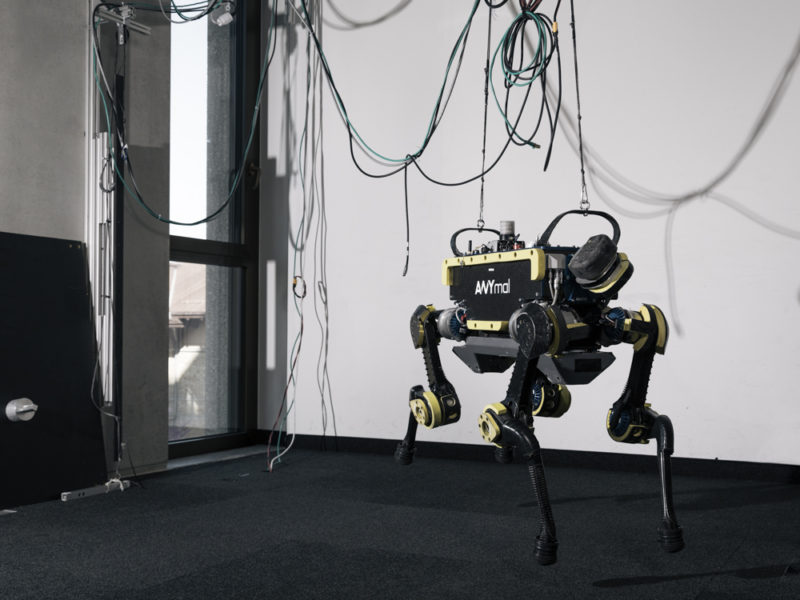

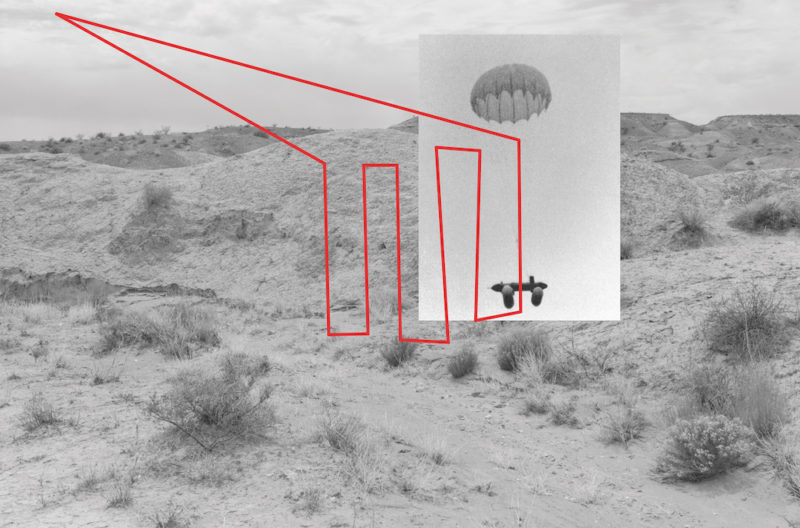

If one wants to take the measure of something, then it is often best to do so from more than one point. More usually these multiple positions occur in space – the same object viewed simultaneously from different places, for example – but they can also occur in time. Let’s consider, for example, something that Peter Fraser noted some years ago: ‘With each series of photographs I choose a different strategy to approach the same underlying preoccupation, which is, essentially, trying to understand what the world around me is made of through the act of photographing it.’ Actually, this was fifteen years ago, and – full disclosure – written to me in preparation for a retrospective exhibition of his work that I was curating for The Photographers’ Gallery, London, yet it could quite easily describe the process that Fraser has undertaken for this most recent book published by Skinnerboox. The title Mathematics might also bring to mind that of an earlier series, Towards an Absolute Zero, but whereas that was metaphorical and referred to ‘a “still” universe’ where a ‘minute shift carries importance’, here the title is to be taken quite literally; as he notes in the afterword, Fraser has made these photographs with the belief ‘that mathematics can explain the world, or at least describe it in a way that approaches an explanation’.

Such a claim, and perhaps the misgivings one might have towards it, is apparent in the first photograph. Here a triangular rack of pool balls recedes upon the cobalt blue felt of the table, the white sitting atop them. While all sports depend to some extent upon numbers – points scored, time taken, distance covered – pool seems amongst the most ‘mathematical’, a table-top exercise of Platonic forms and Euclidean geometry. Even the balls themselves have numbers upon them, yet while these might help us to describe their relative positions within the rack as wrong, could they explain it? Here, one might feel that mathematics is less a structure underlying the world – and the work – than one placed upon it.

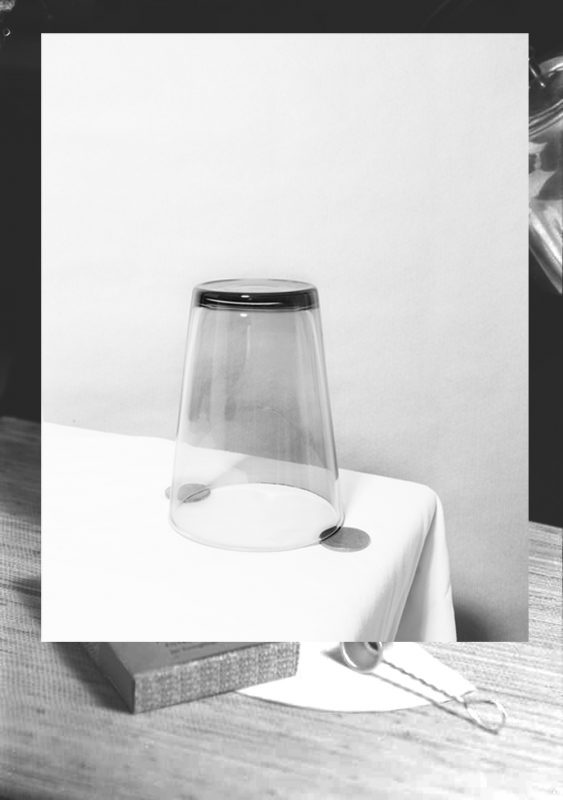

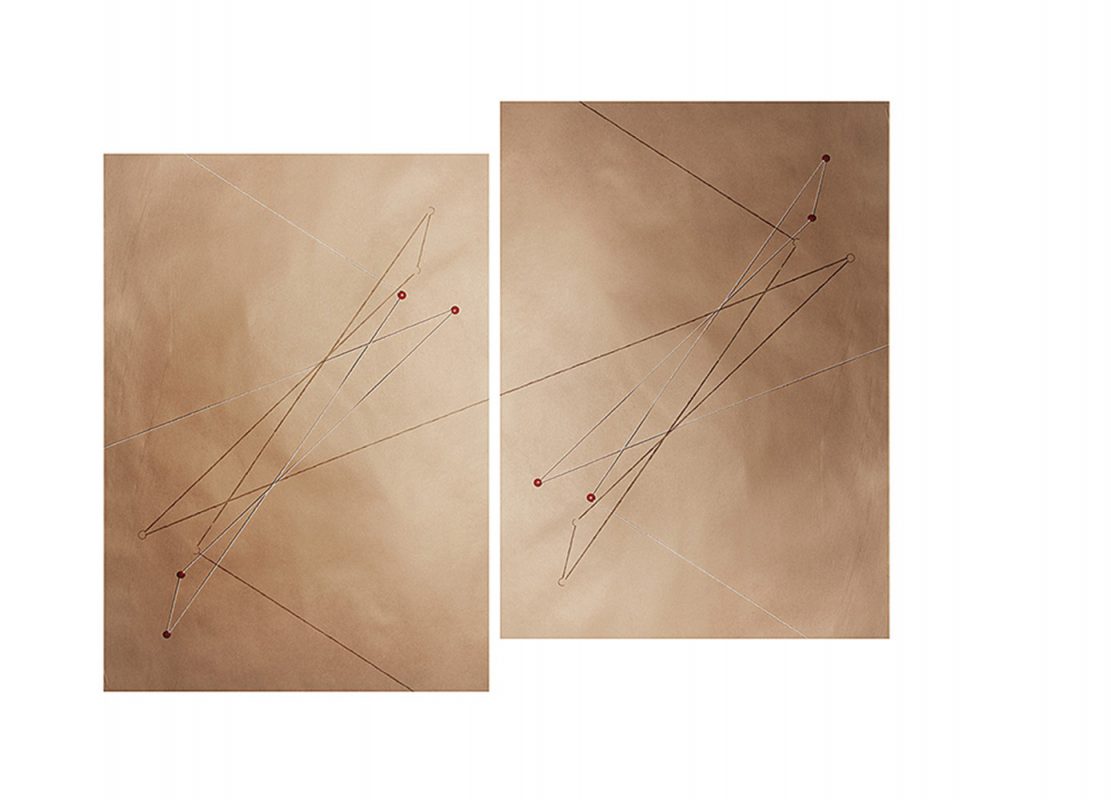

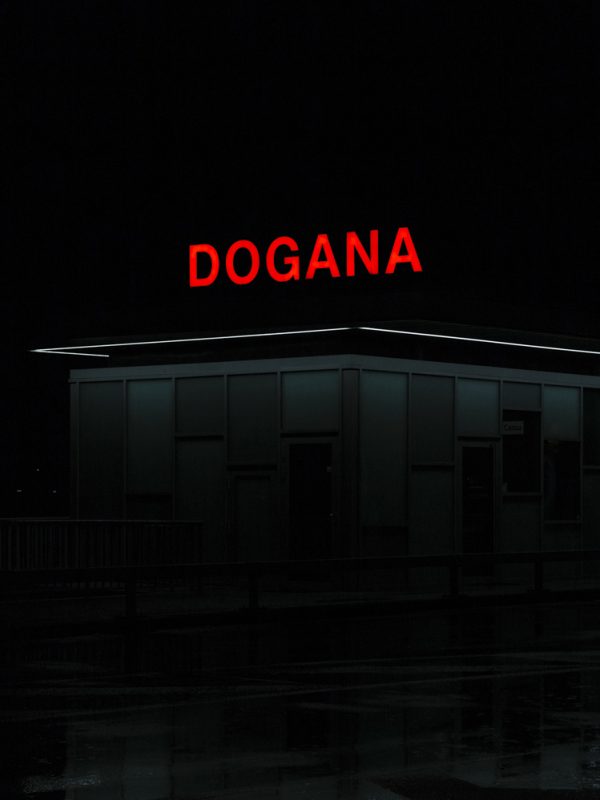

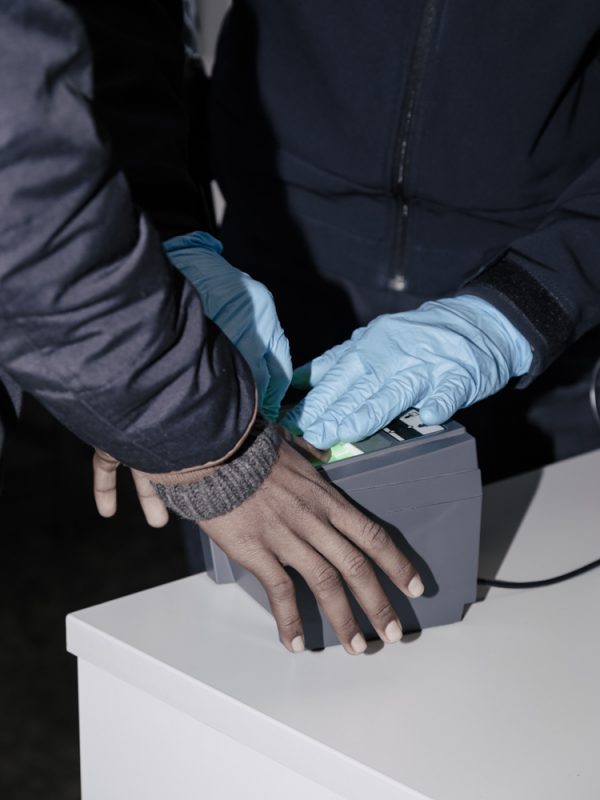

The work becomes far more compelling when such an organising structure seems less apparent and given the diversity of pictures here contained, this is often. Indeed, the universalism that mathematics seems to hold for Fraser allows him to photograph far more widely than he has for some time. (I didn’t then mean geographically, although this is also true: whereas many earlier projects were bound by a form of geographic constraint – a particular journey, or city – here the photographs are clearly made in many different countries.) I am reminded often of pictures found within Two Blue Buckets, Fraser’s seminal book, which, through its recent republication as a director’s cut, might itself become another point, or two, from which to view this more recent work. One might also come to think it almost inevitable that there should be two books called Two Blue Buckets, both similar, each different. The irregular curves along the back of a bay horse; the weathered paint of a corrugated building; the arrangement of domestic objects; the interiors of sacred spaces: all can be found in both books, and if the democratic vision he borrowed early from William Eggleston insisted that yes, even this – the merely familiar – was worthy of our consideration, then Fraser now allows that ‘this’ might also include that which is extraordinarily familiar, such as the Matterhorn, or great works of architecture, or of art (or their copies, at least).

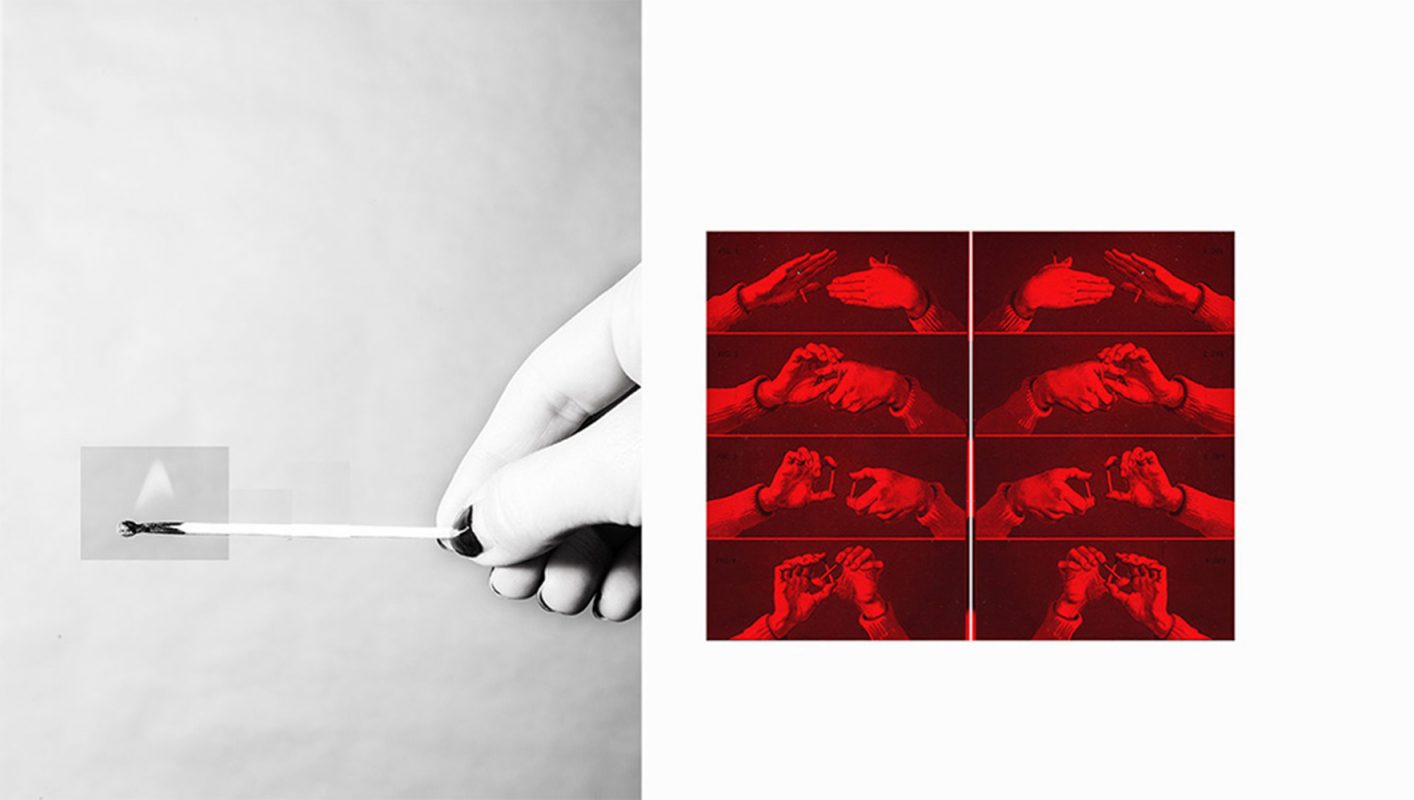

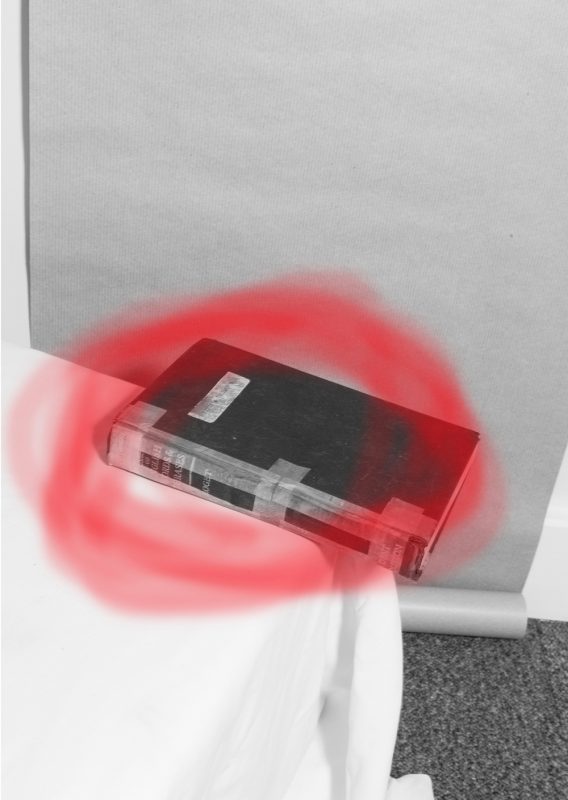

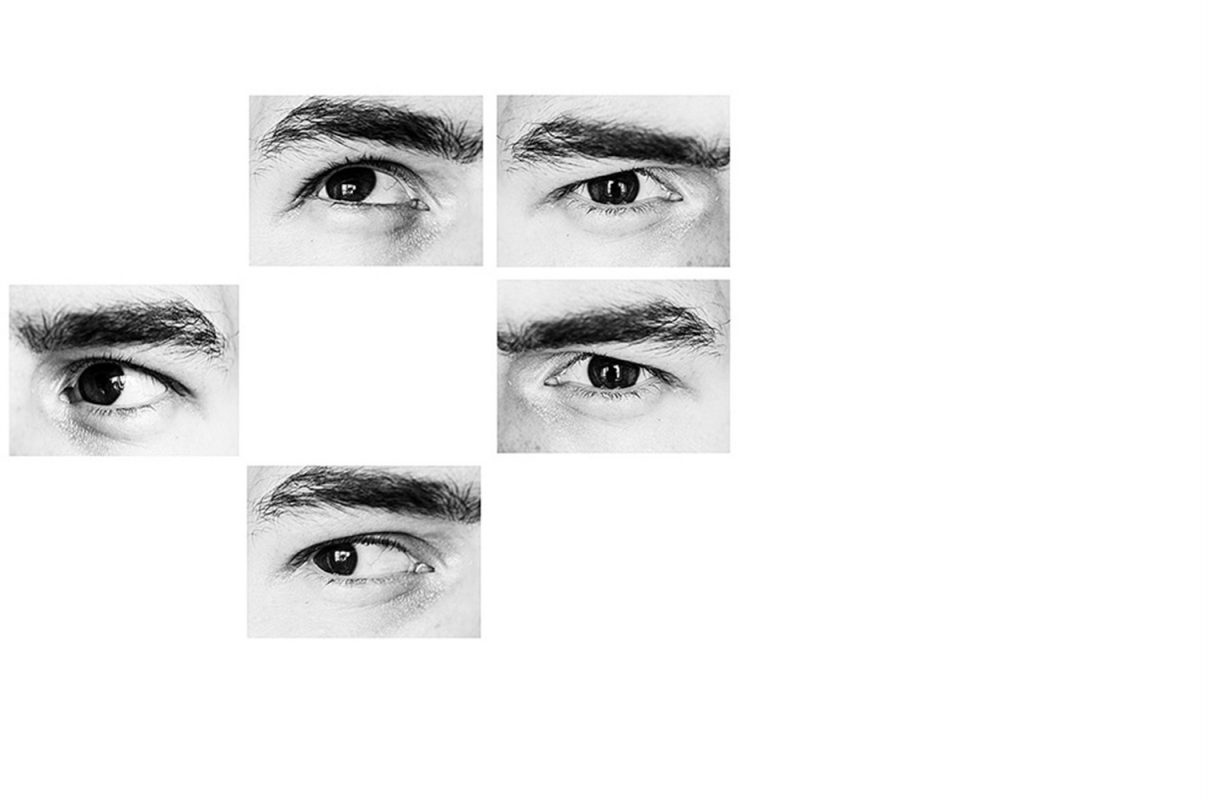

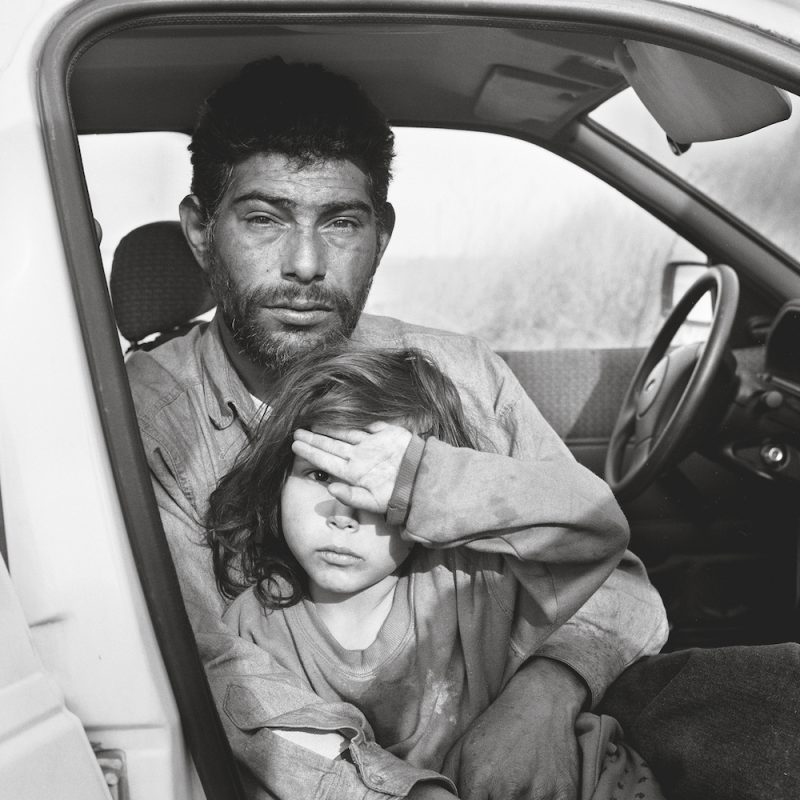

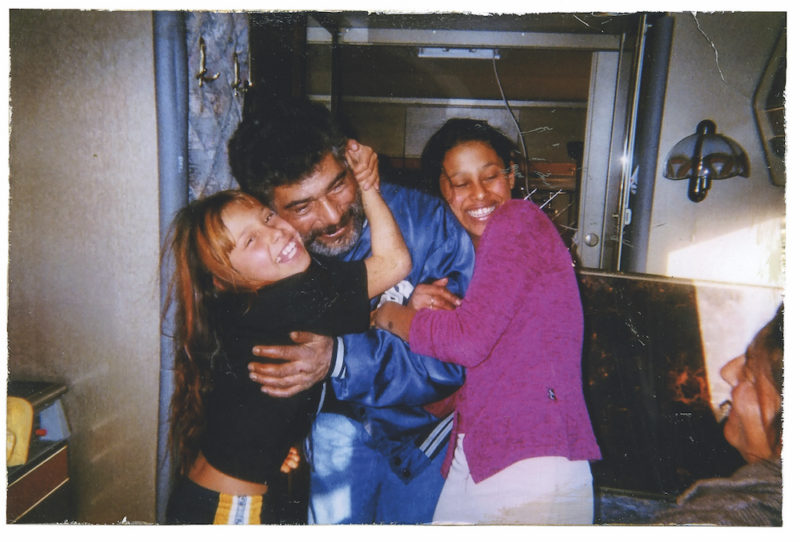

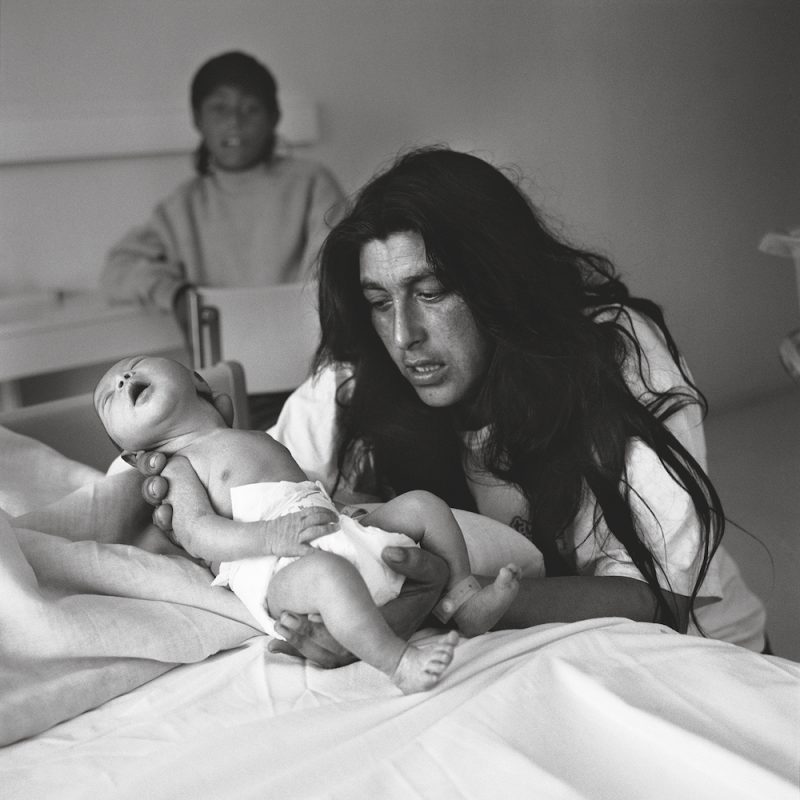

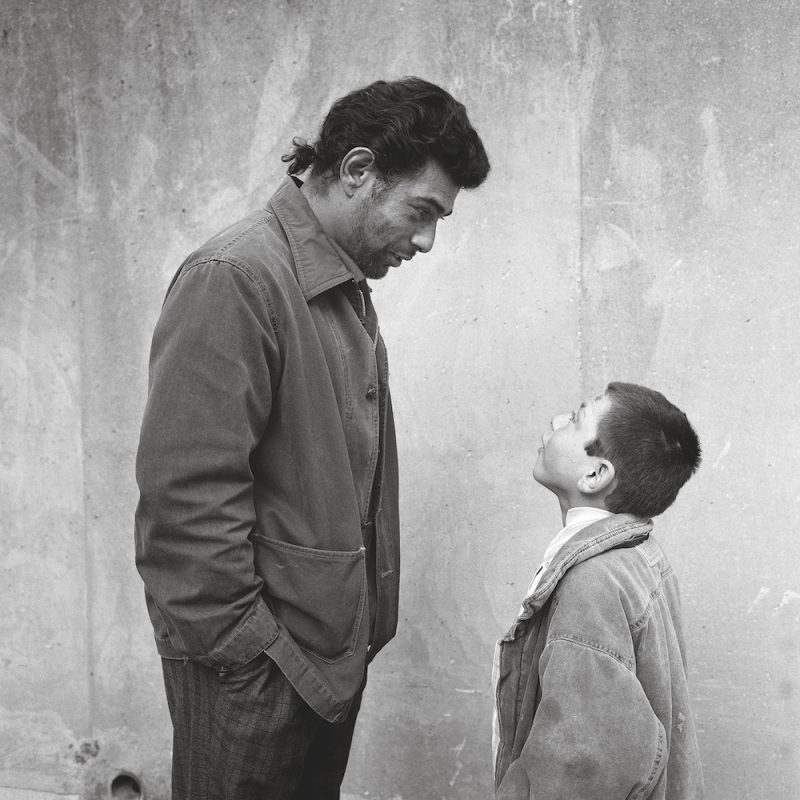

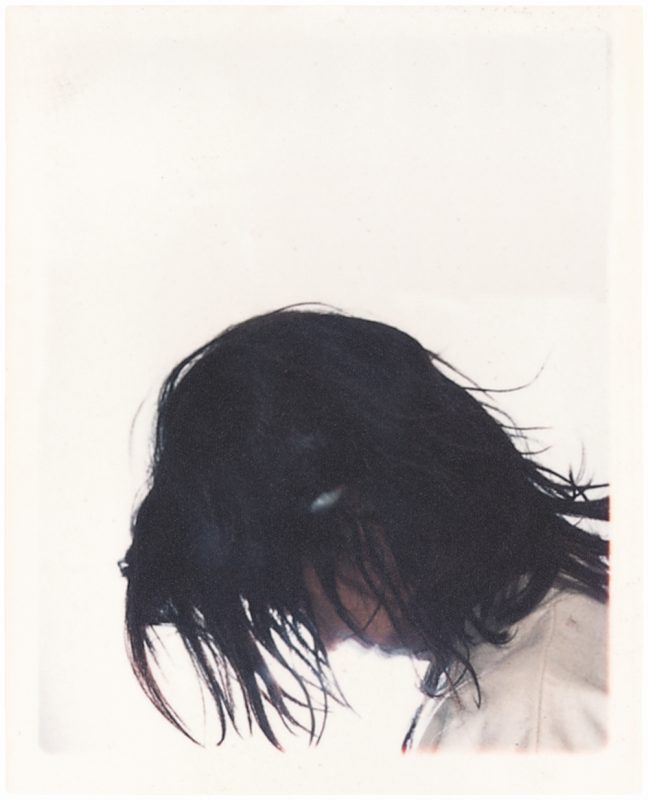

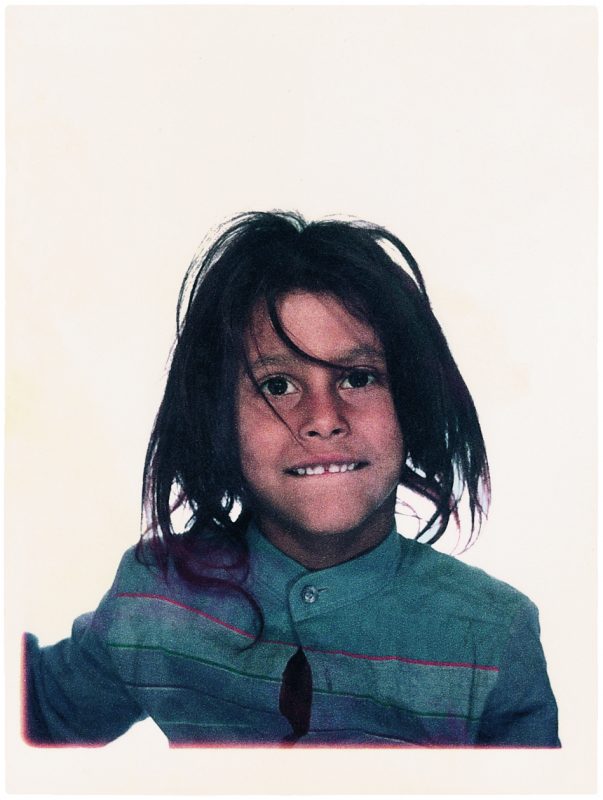

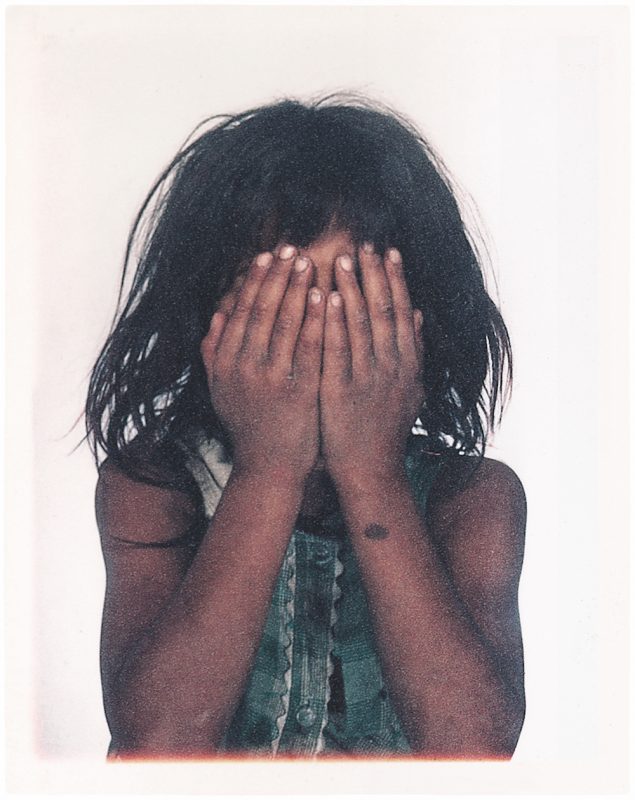

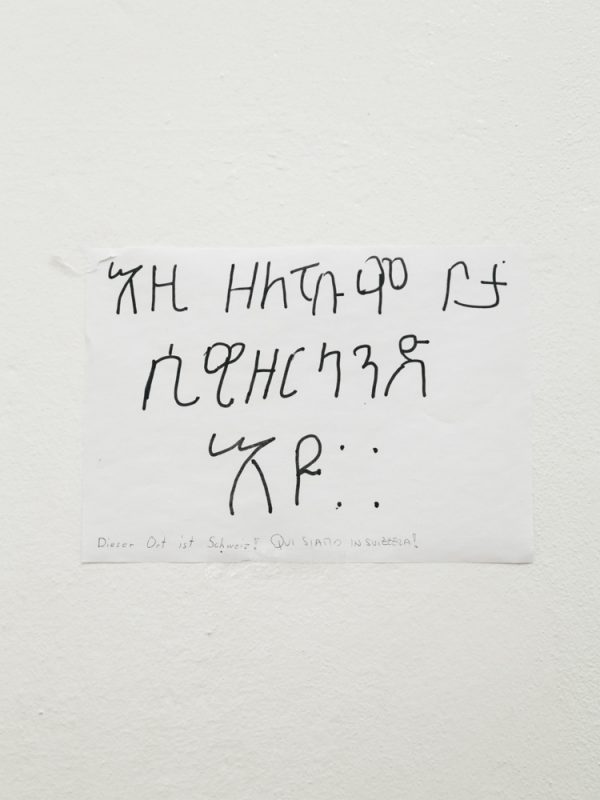

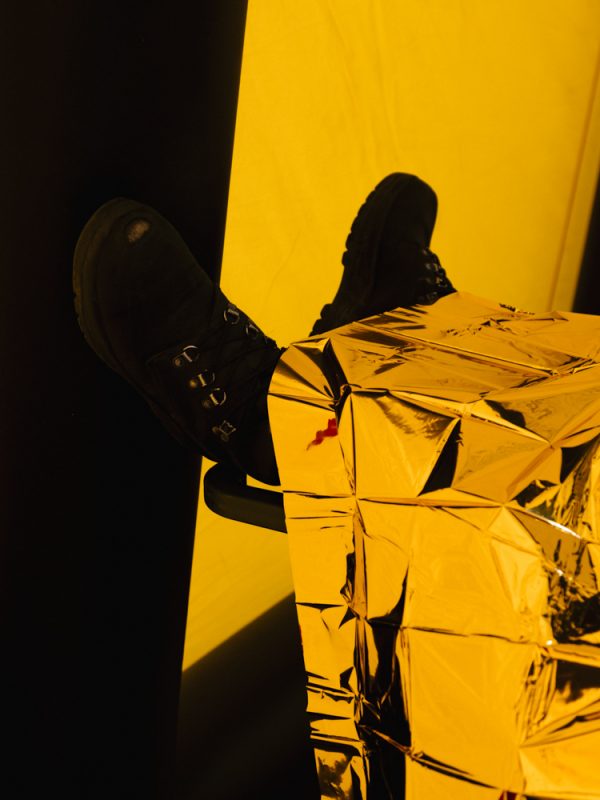

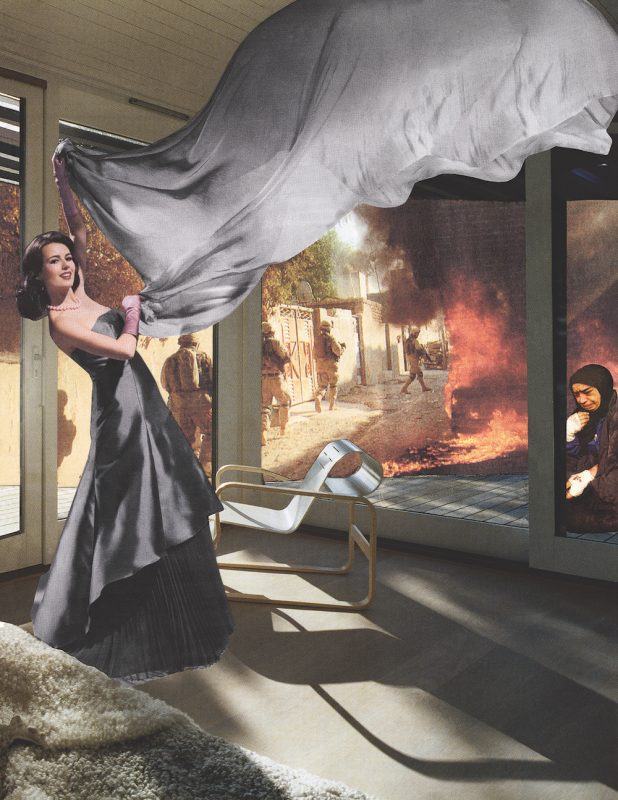

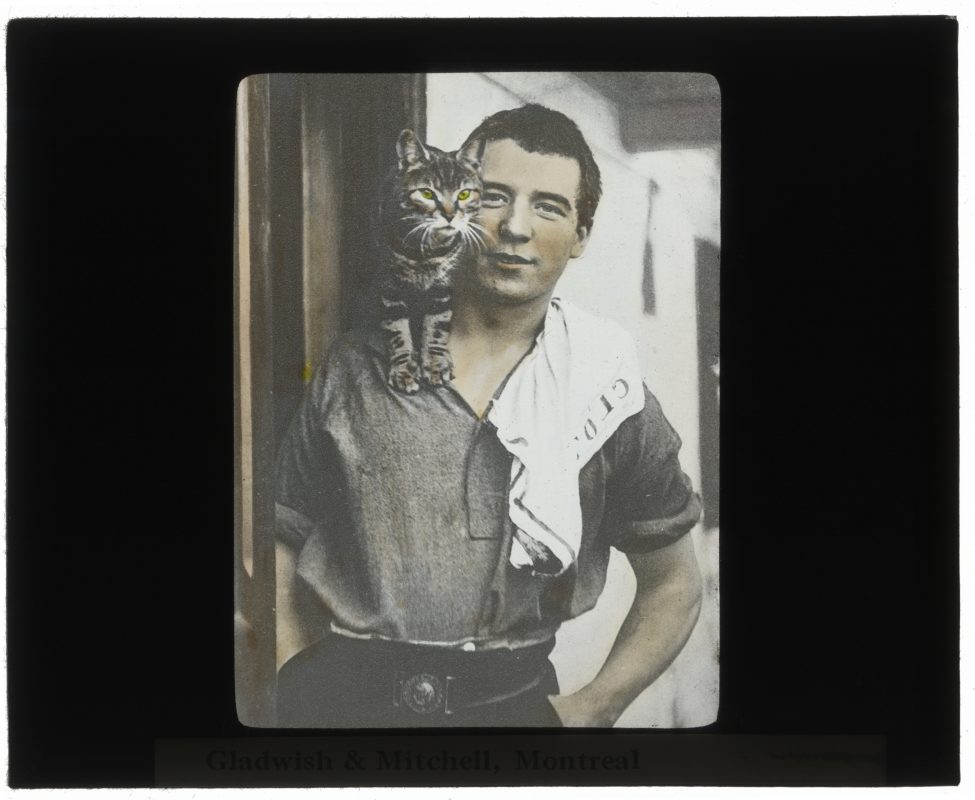

To this list we might also include people, who here return to his work. Before making each portrait, Fraser asked each person ‘to imagine that they had just discovered that something they had always believed to be true had just been found to be a lie.’ Whether, in the terms established by this work, such a discovery might be considered an addition to or a subtraction from their sense of the world, or themselves, is left uncertain, as uncertain as their expressions, yet the premise is far less so: ‘had just discovered’ suggests that the knowledge had been accepted in a manner that ‘had just been told’ surely wouldn’t. What we know to be true depends largely upon what we believe to be true, and here we return to the subject that has been at the very heart of Fraser’s practice for three decades or more: the notion of faith. In the mid-Eighties he wrote that, ‘The sacred is everywhere and resides in the most unlikely places’, finding it then in the knotted net hanging in a stable, or the Marian embrace of an Avery weighing scale (although whether this was a Nativity, or a Pièta, one would never know). Now, Fraser’s faith might have shifted, but it is made manifest in similar things. One does not have to hold such a belief to believe that others do, nor that that belief might create things of great beauty and intelligence, whether that is the strange scintillation of what seems to be a flooded quarry, or the calligraphic splendour of the main dome of Blue Mosque.

To consider one last picture: here we are invited to look down, obliquely, across the rooftops – polygons of terracotta and slate – of what one presumes to be a European city. The bright sunlit planes of the stuccoed façades throw into relief the shadow thrown across – and up from – the foreground, spiking flatly across the complex of shapes below. And yet where might we situate ourselves in such a view? Given our downward glance one can assume that we are somewhere high upon the building casting the shadow, yet our position is unclear. We are both elevated and umbral, never knowing how far from that threshold to lucidity we are. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Peter Fraser

—

Jeremy Millar is an artist, and Senior Tutor at the Royal College of Art, London.