Buck Ellison

Perfect White Family

Essay by Daniel C. Blight

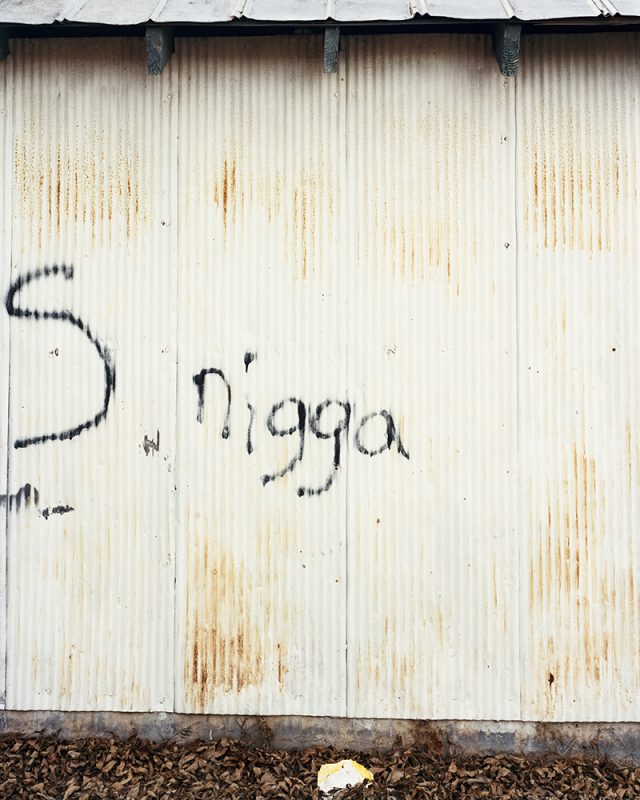

Picture this if you can. The obsequious glow of white skin, in your house, at your work, in your mirror. If you “don’t see race”, see it now. See the thing you were taught to ignore. This signifier — this sallow epidermis — is what renders you invisible. Without your conscious permission, it places you at the unseen centre of what it is to be human. The ‘unmarked nature of whiteness derives from it being the centre point from which everything else can be viewed’, writes Steve Garner in his Whiteness as a kind of absence.[i]

White people are ghosts, invisible to themselves.

Photography is the social and technological history of “seeing white”. It finds its origins in the long 19th century and is often framed as a miraculous invention pioneered by the polymathic glow of elite European men. Sir William Henry Fox Talbot, the imperious Knight of the British Empire. Nicéphore Niépce, the son of a wealthy French lawyer. Photography then rapidly becomes the visual tool of European Imperialism — power, war, continued colonisation. At first, wealthy white men set out to photograph the world around them; “dark” things they find outside the centre of whiteness. White skin commands the signification of purity at home and black and brown “natives” form the subjugated portrait of the Grand Tour abroad.

Google Image search “family portrait”. The algorithm offers us a picture of white familial normativity. Perfect teeth, rose-tinted skin, wavy locks of hair. Race is also a question of class, of course. The same algorithm delivers us a picture of wealth: three of the first ten images in the search return a photograph of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge with their two young children. Immaculate teeth, snow white skin — human “perfection”. Where does this image come from, why does it appear so avaricious and white, and what happens if we turn it against itself?

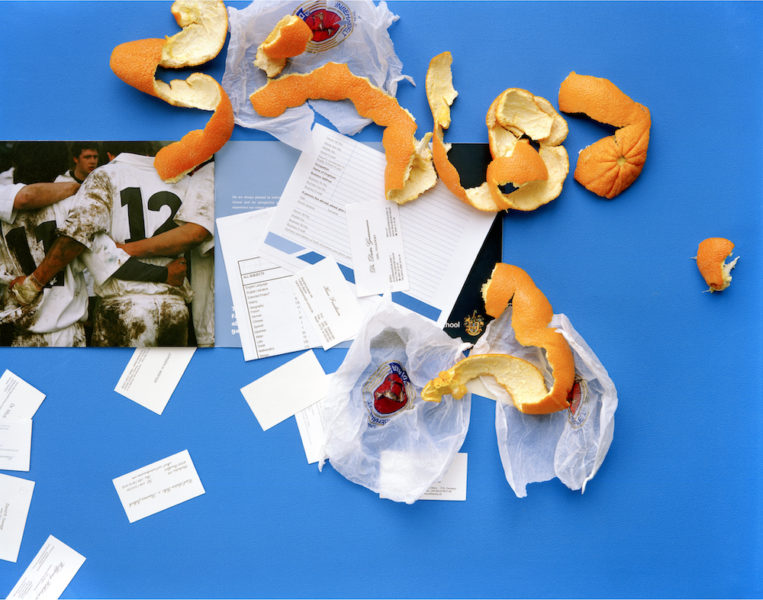

Buck Ellison flips the antipathy of such an image on its side. His “perfect” family is an image of acknowledgement; one that references a history of art bound to white, upper-class familial representations, from Dutch Golden Age painting to contemporary photographs of monied elites. But it is also an image of critique; one which captures the currency of financial aspiration and success in the present-day West. The psychology of wealth-making underpins our consumerist drives to accrue money and the sense of power and independence that often comes with it. As a recent research paper, The Psychology of Wealth[ii] notes, ‘Individuals endorsing the beliefs that self-worth and net worth are intertwined, that success is defined by how much money they earn, and that money helps give their life meaning were more likely to have attained a high-income level.’ In short, if you believe you are a high-value person in social terms — if you are able to perform that kind of vanity — you stand more chance of earning highly, so the story goes. One might pose the question here: what is the relation between narcissism, wealth and cultural traits associated with the social construction of whiteness?

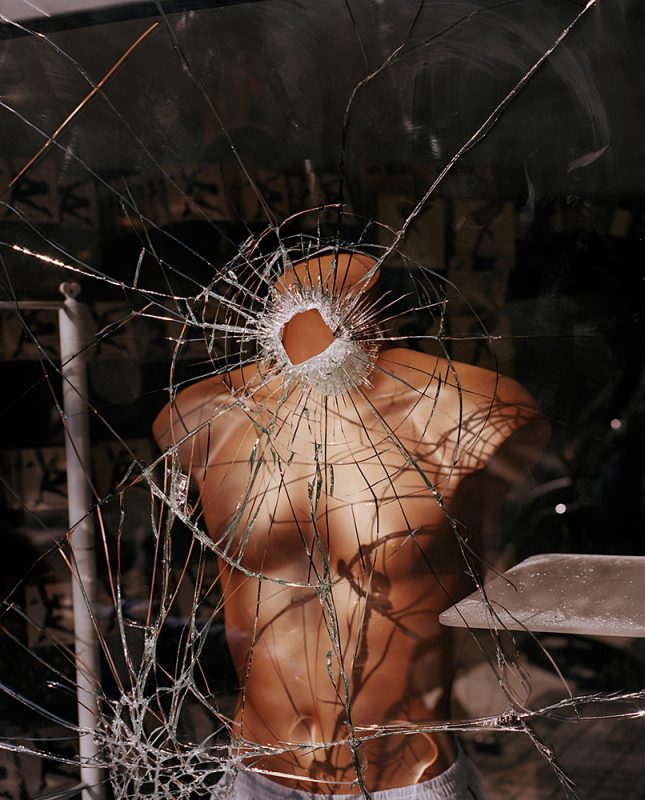

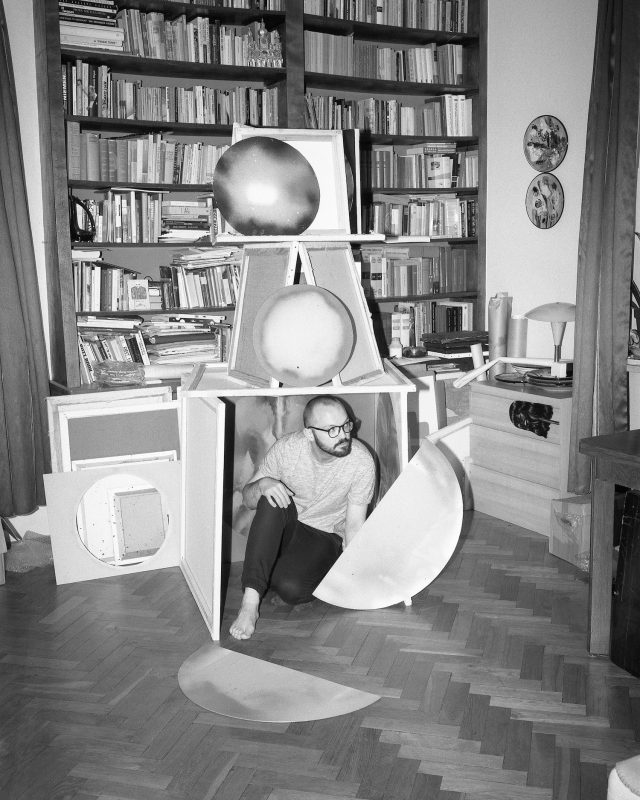

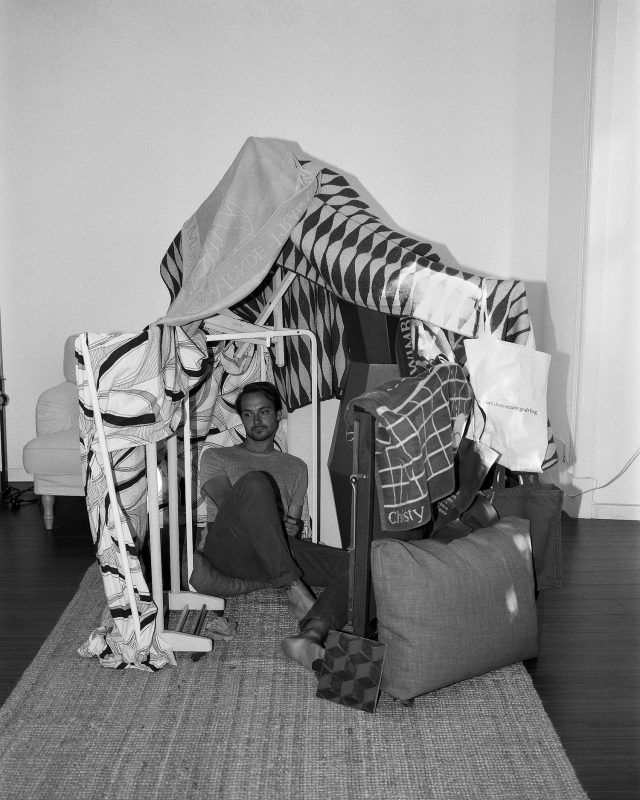

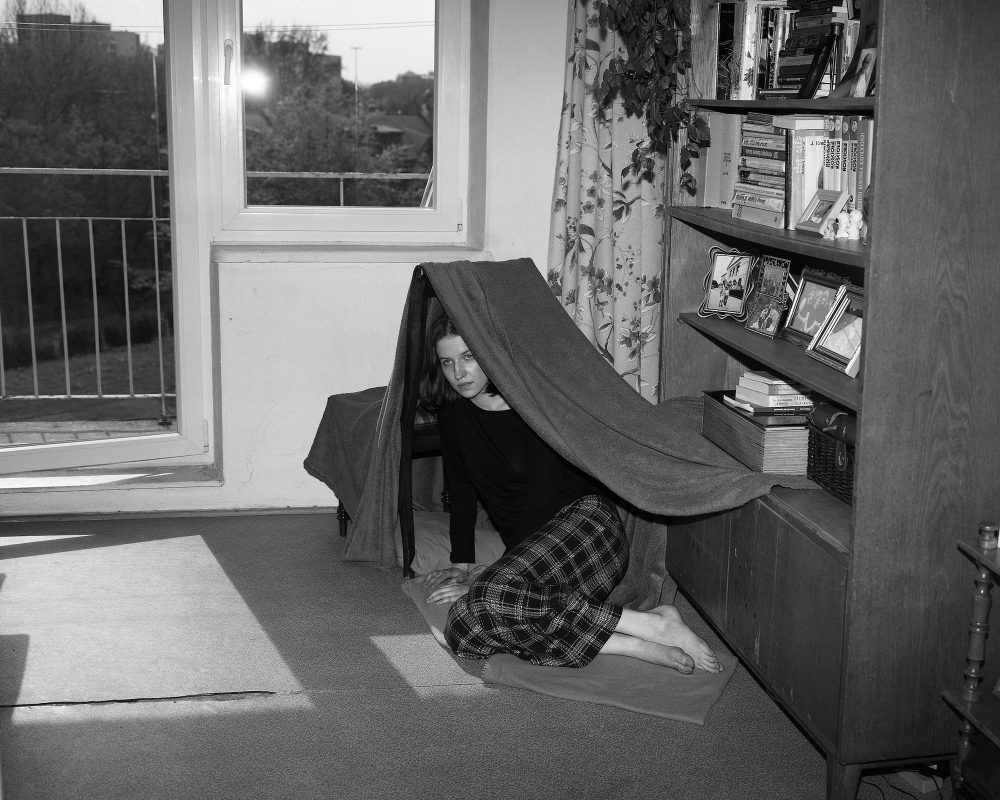

In a period of ludicrous economic inequality, the photographic representation of this type of domestic space provides a seldom-granted look in to a 1% culture which owns 90% of American dollars. Ellison visually documents this space, and at the same time renders it artifice, fiction. As Gillian Rose writes, domestic space is ‘connected to the public space of political, economic and cultural relations’[iii] and we might therefore interpret it as a space that is constructed. While reflecting a social class that is very real indeed, the subjects of Ellison’s photographs nonetheless perform their identities, assembling the meaning of the space around them. How might this function, as an image?

One of Ellison’s visual references is 17th century Dutch painting. As Martha Hollander notes in her An Entrance for the Eyes[iv], Dutch painters designed a complex and thoughtful series of signifiers into their images which in equal parts documented and allegorised the lives of the subjects featured. Ellison has made a series of photographs that work similarly to reveal various tropes and details. An American war of Independence drill manual, a First World War cannon, a diamond engagement ring, a phone call made or taken in the Ritz-Carlton.

The Prince Children, Holland, Michigan, is a semi-formal group portrait. The photograph gives us a number of venerably posh signifiers: flowery upholstered furniture (good taste); a large, welcoming fireplace lined with parquet woodwork (a warm and wholesome environment); plenty of pictures and books (knowledge is power); the boy wears his polo-neck tucked-in (smart, well bred) and the girls sit or stand in plaid skirts and knee-high hosiery (European cultural heritage, check). This type of family photography, as French writer Jean Sagne notes,

puts in place a system of signs, which translate

into the image of a class…. The conformity to

the model, the constraint imposed on the individual

to bend to [certain] rules can but translate into

a voluntary assimilation, a recognition of a social code.[v]

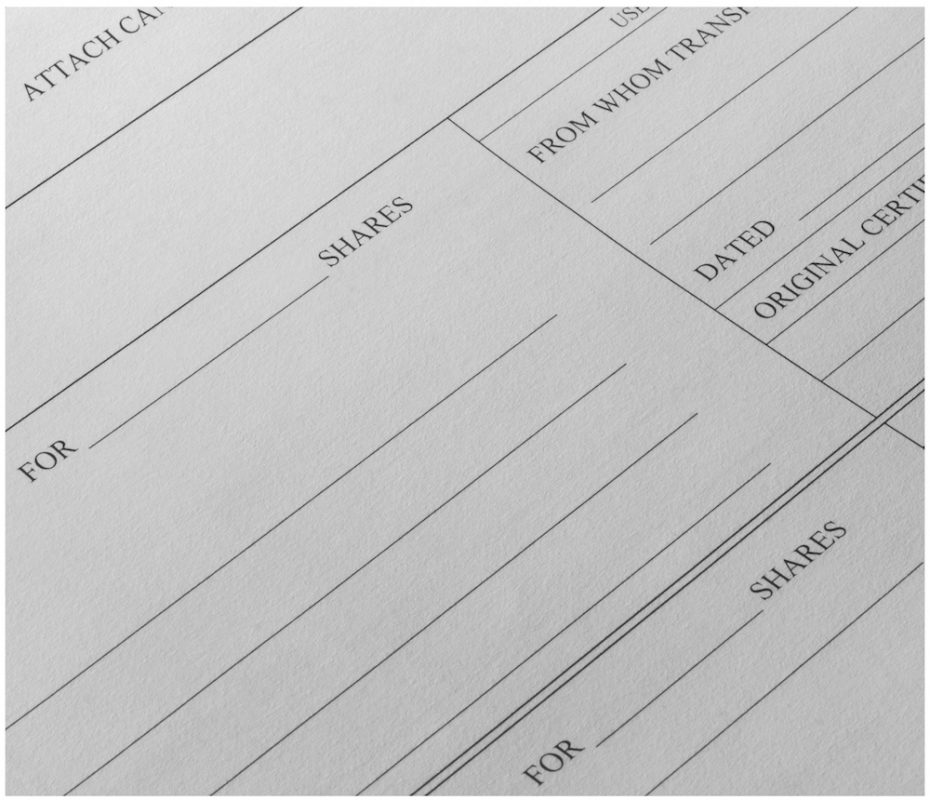

I cannot claim to know these people, but I am socialised to recognise the image they project for I have come to unconsciously desire it myself. As Kalpana Seshadri-Crooks shows in her Desiring Whiteness,[vi] whiteness is the ‘master signifier’ to which all other racial categories must be submitted. White people are thus lured towards it; our lives lived in a state of flux between ignorance of what we are and a certain crisis of knowing, somehow, that we are living in a state of denial; a refusal to give up that chimerical promise that was offered to us, for nothing, at birth. It is not our skin that makes us white, but rather the way we act upon the world. As Cheryl Harris has shown[vii], whiteness was in part devised as a system of property ownership, and it is with the notions of property, assets and profit that white people continue to be obsessed. In this respect, whiteness is capitalism, and we barely know it.

Photography complicates questions of race and class considerably. As a medium shifting between documentary and fiction, it both reaffirms the dynamics of social, political and economic power and at the same time places them out of reach. Ellison’s pictures are enigmatic in the way that they both “image” and “imagine” a certain kind of reality. To look at the family group is, as Philip Stokes writes, ‘to add the assumption of a whole thicket of connections between the sitters; most viewers allow themselves the pleasure of extravagant supposition.’[viii] We, as viewers, do not know who these people are, but we can suppose who they remind us of, if not directly ourselves. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist and The Sunday Painter, London. © Buck Ellison

—

Daniel C. Blight is a writer based in London. He is Lecturer in Historical & Critical Studies in Photography, School of Media, University of Brighton and Visiting Tutor, Critical & Historical Studies, School of Arts & Humanities, Royal College of Art. His first book, The Image of Whiteness: Contemporary Photography and Racialization is forthcoming from SPBH Editions co-published with Art on the Underground.

References:

[i] Garner, S. (2007), “Whiteness as a kind of absence” in Whiteness: An Introduction. London: Routledge.

[ii] Klontz, B.T., Seay, M.C., Sullivan, P. and Canale, A. (2014), The Psychology of Wealth: Psychological Factors Associated with High Income. Journal of Financial Planning, 27:12. Denver: Financial Planning Association.

[iii] Rose, G. (2003), Family photographs and domestic spacings: a case study. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. London: Royal Geographical Society.

[iv] Hollander, M. (2002). An Entrance for the Eyes: Space and Meaning in 17th Century Dutch Art. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

[v] Sagne, J. (1984), L’atelier du photographe. Paris: Presses de la Renaissance.

[vi] Seshadri-Crooks, K. (2000). Desiring Whiteness: A Lacanian Analysis of Race. London: Routledge.

[vii] Harris, C. (1993). Whiteness as Property. Harvard Law Review, 106:8. Cambridge: The Harvard Law Review Association.

[viii] Stokes, P. (1992), “The Family Photograph Album: So Great a Cloud of Witnesses” in Clarke, C. The Portrait in Photography. London: Reaktion.