Clare Strand

The Discrete Channel with Noise

Essay by Duncan Wooldridge

Made of Porcelain Enamel on Steel, with a mechanical precision that belies their hand-painted fabrication, László Moholy-Nagy’s EM1, EM2, and EM3 (1923), often known as the Telephone Pictures, prophesied the role that new materials and new technologies would play in artmaking in the future. Created by calling a fabricator, giving instructions over the phone, with a grid and commonly defined reference materials, including colour charts, the work foretold a host of artistic strategies, including the delegation of work to other agents as well as the notion of the artwork as an ‘instruction’ or ‘piece of information’. Distant was the human hand, eliminated in the service of new technologies, though the marks of experimentation were nonetheless vivid, the work appearing strikingly industrial in comparison with the artist’s, and peers, other production of the time. Moholy-Nagy, who produced the Telephone Pictures a year after completing his equally significant essay Production-Reproduction, sought to use technology as a means to challenge what the artist described in his writing as a fundamentally ‘reproductive’ tendency within the art of the time: the production of formally and intellectually generic methods that reproduced the ways of seeing of the present and past. Moholy-Nagy was not critical of the artwork’s capacity to be made multiple, in fact celebrating technology and reproducibility; he was critical of art which reproduced conventions, a production he likened to little more than uncritical virtuosity.

Technology would unlock new methods of artmaking and new ways of seeing, Moholy-Nagy surmised. The significance of his images and writings are not lost, certainly not in artists’ use of the technological, but the calls that he made – to experiment with photography and to understand the technology that we use – certainly seems to have been rarely heeded. Clare Strand’s The Discrete Channel with Noise (2018), shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2020, is a work which picks up systems and technologies of communication in order to treat them not as unspoken facts but as material. Beginning with the propositions of Claude Shannon’s Information Theory, it puts to the test the logics of systematised communication, through the photographic image, as it has moved from immanent image to complex object. Strand’s title is borrowed from the second section of Shannon’s groundbreaking 1948 essay A Mathematical Theory of Communication, republished as a book in collaboration with Warren Weaver the following year. Strand’s project – to remake a series of black and white photographs remotely, by painting from a series of instructions arrived at from a gridded original image, communicated to her across the English Channel whilst on a residency in Paris, shifts and reconfigures Moholy-Nagy’s propositions in important ways, addressing the ramifications of what he foresaw and Shannon made manifest. Strand’s strategies, as a result, play with and amend our relationships to technology, drawing comment on the information society and its digital swarms.

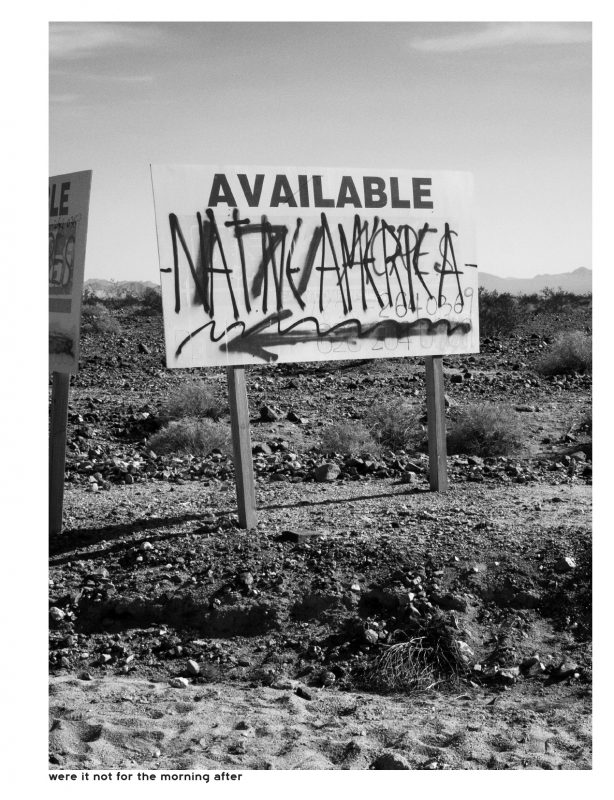

A 2010 work by Clare Strand, entitled The Seven Basic Propositions, pits seven 1950s Kodak slogans against the Google Image Search engine. For each claim made for photography by Kodak – to ‘authenticate’, ‘detail’, be ‘inexpensive’, be ‘colorful’ [sic], to ‘last’, to be ‘fast’, and to be ‘so expressive’ – Google throws back generic image after generic image. What is remarkable is not that the familiar search engine provides its own index or archive – or that it has a quantity-biased window onto the world that comes into stark relief when asked to perform semantic or qualitative tasks. It is that the images it supplies are so generic, so dominated by the banal, that claims to the romance or significance of technology come crashing down. Here Strand overtly ties together the question of production with that of distribution. The first of Strand’s works to overtly tackle forms of image circulation, The Seven Basic Propositions has led to an array of diverse works, which all speak about what is and is not made visible: Strand’s The Happenstance Generator (2015), Research in Motion (2014), Men Only Tower (2017), and Ragpicker’s Tower (2012), and her installation All That Hoopla (2016), all speak to how circulation happens, structures and limits.

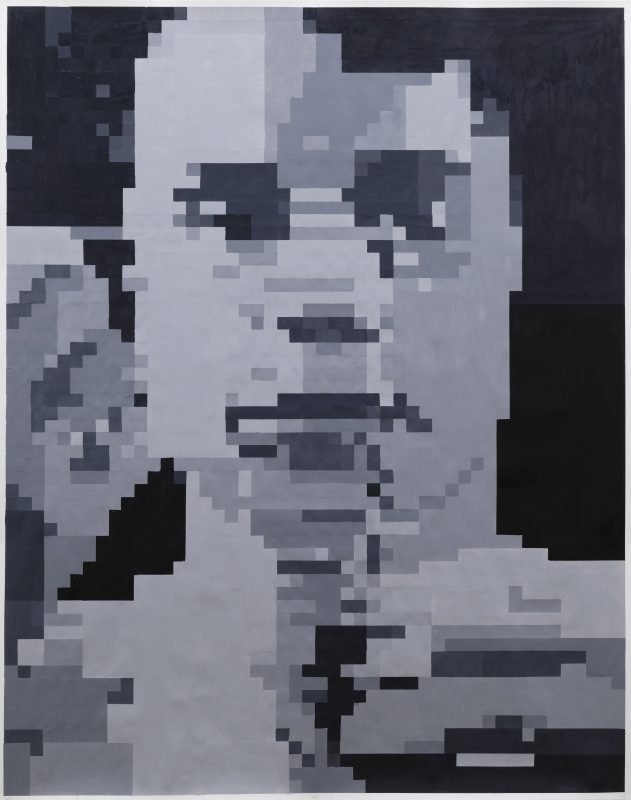

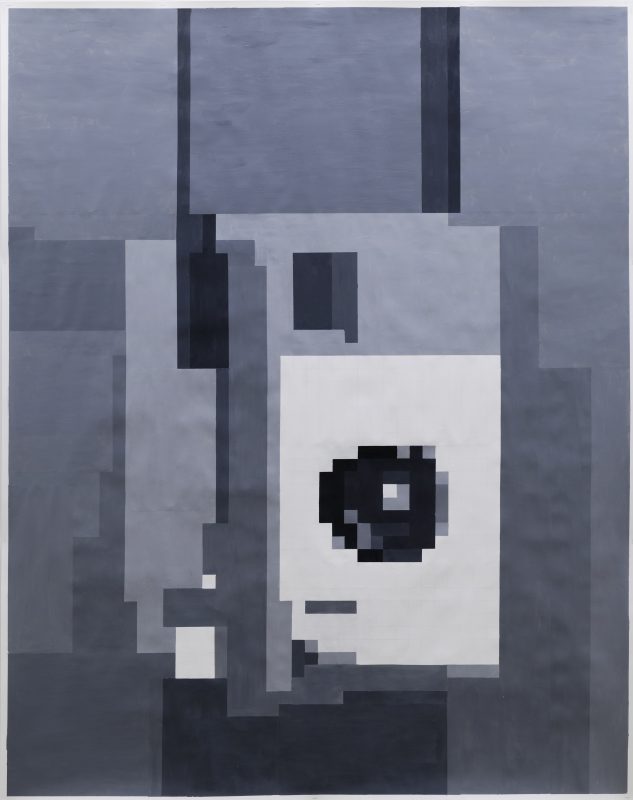

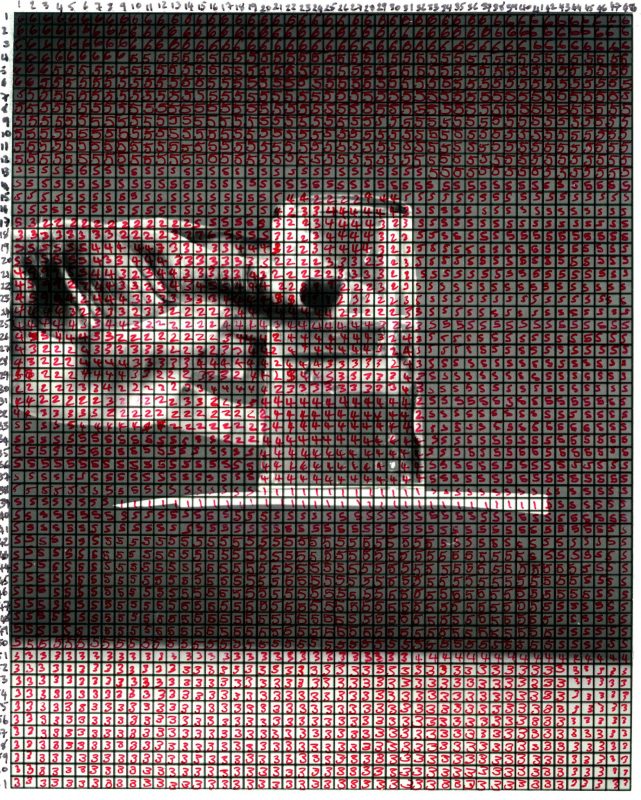

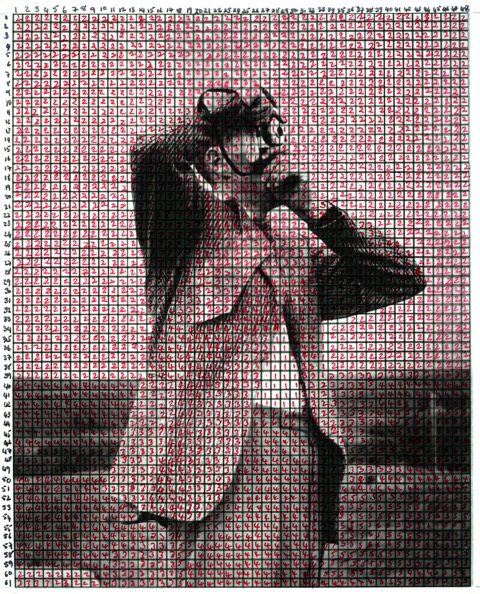

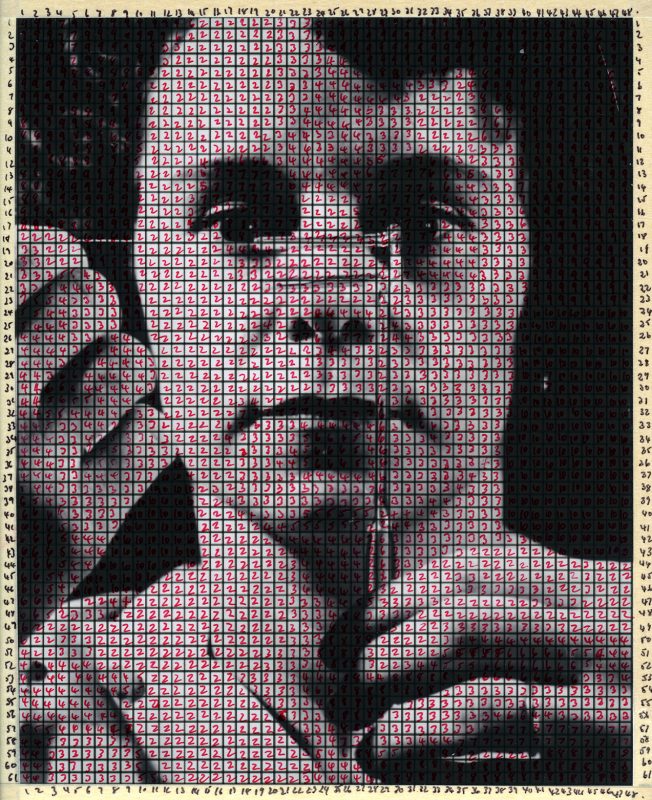

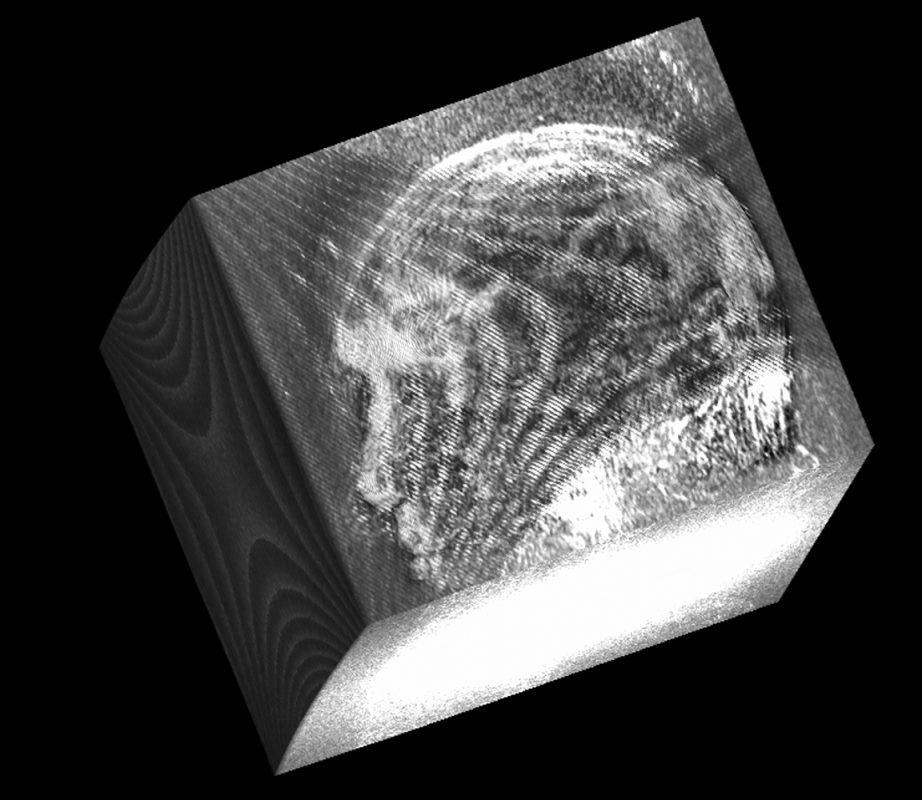

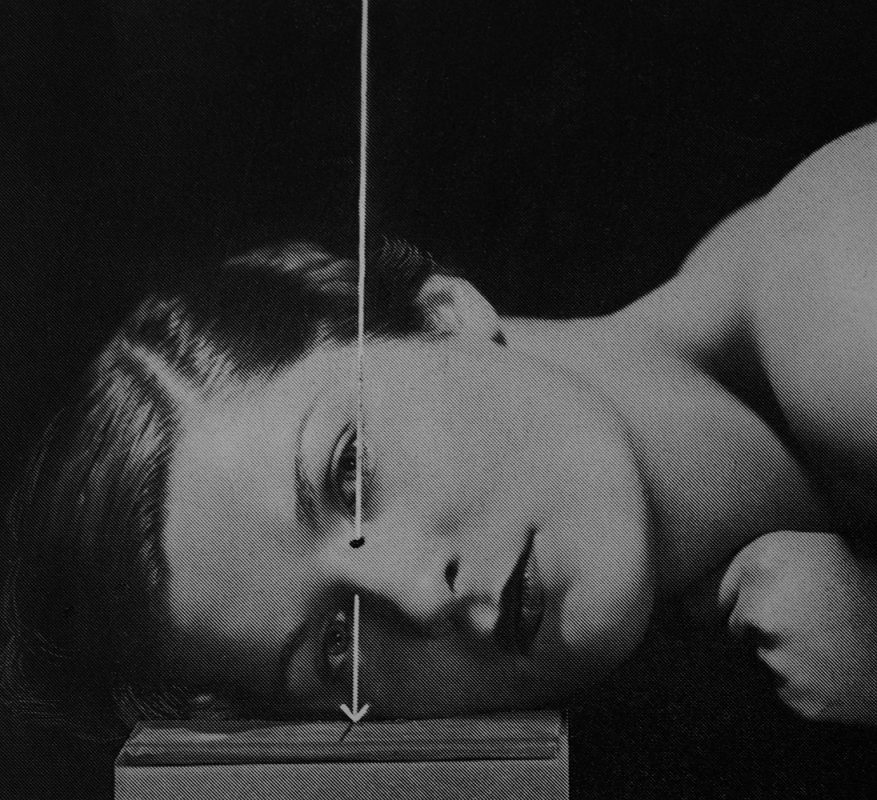

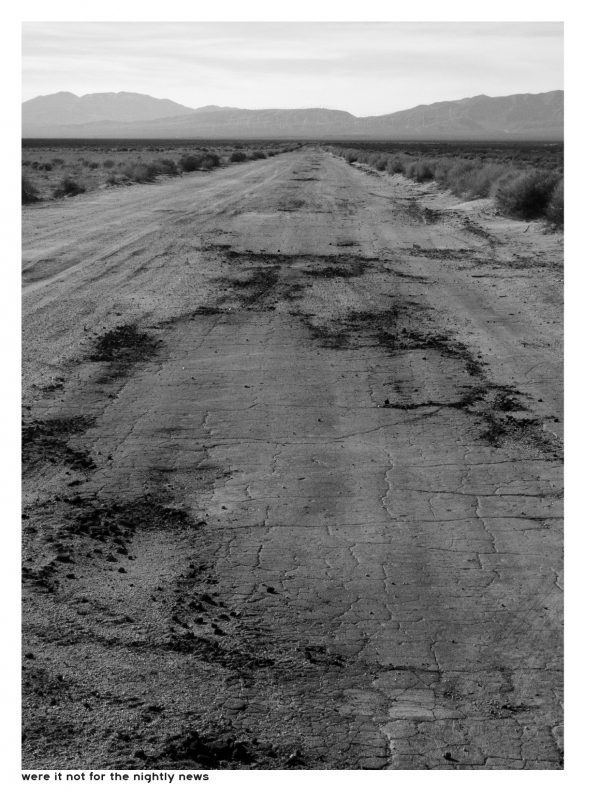

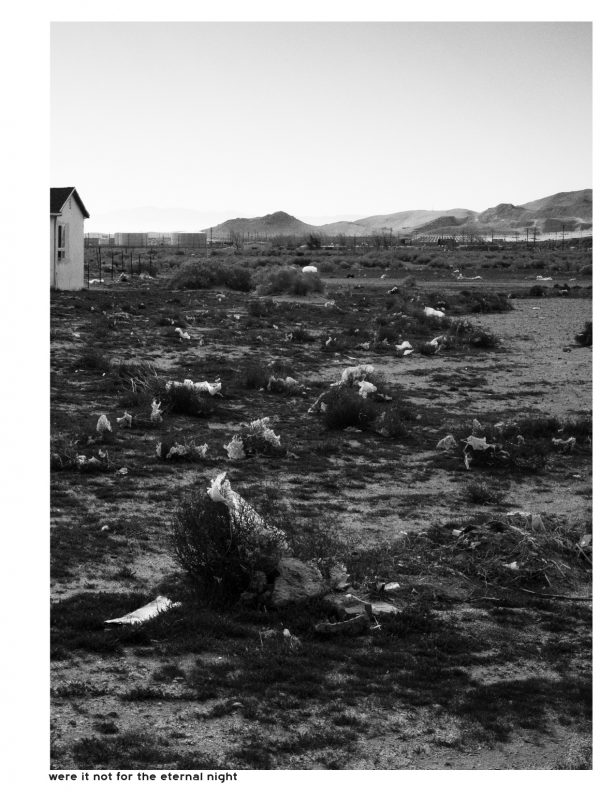

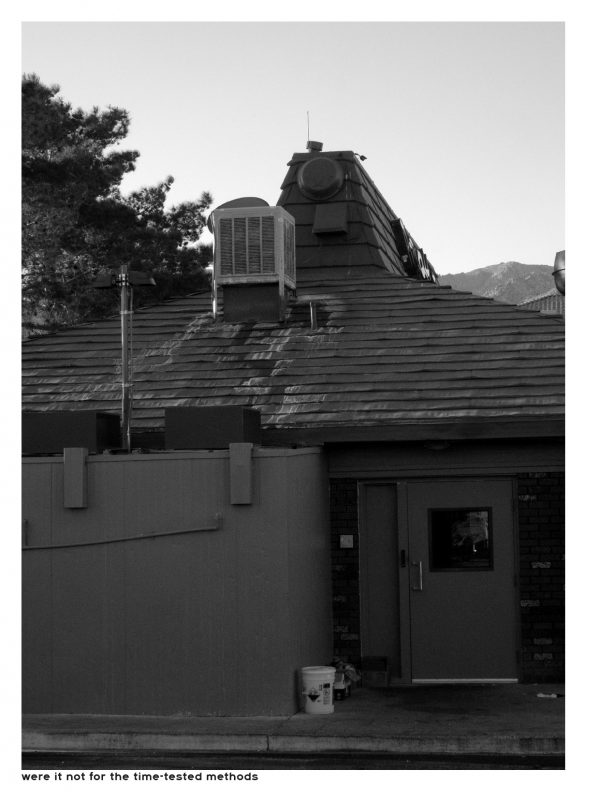

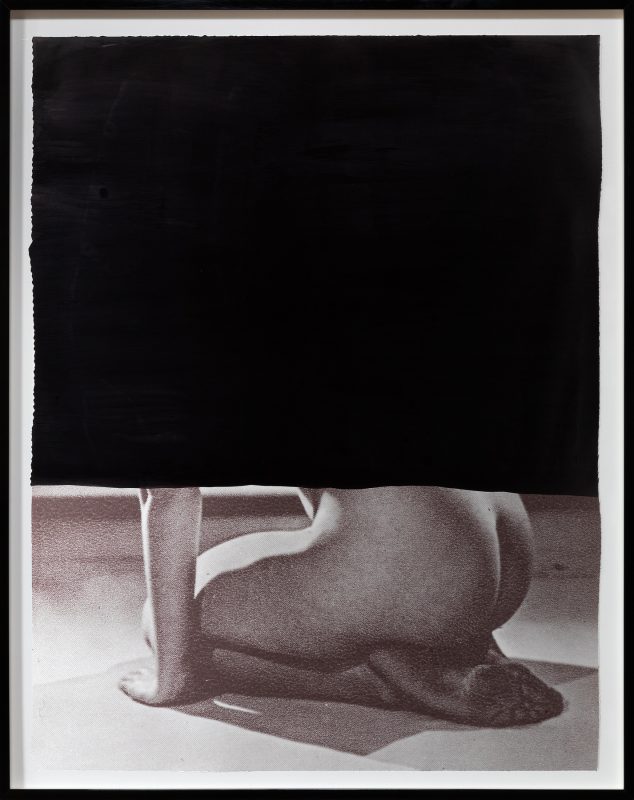

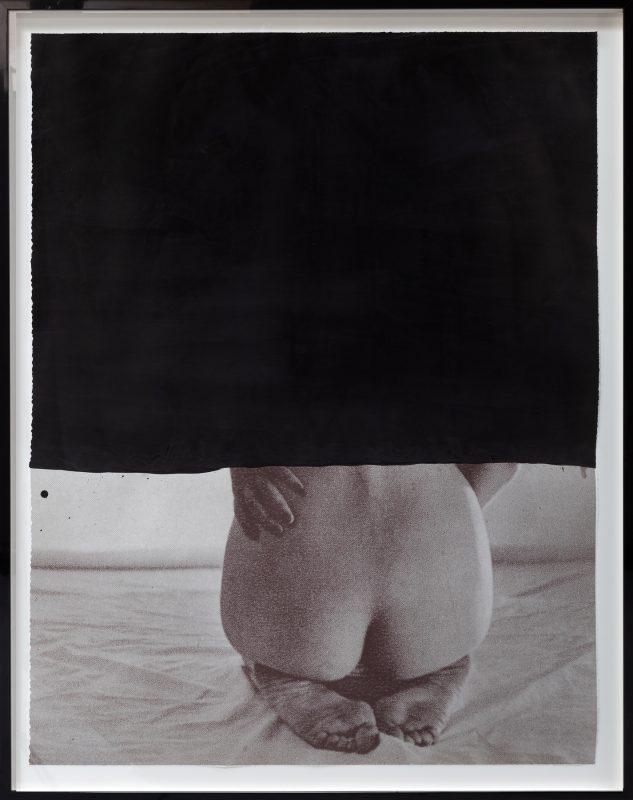

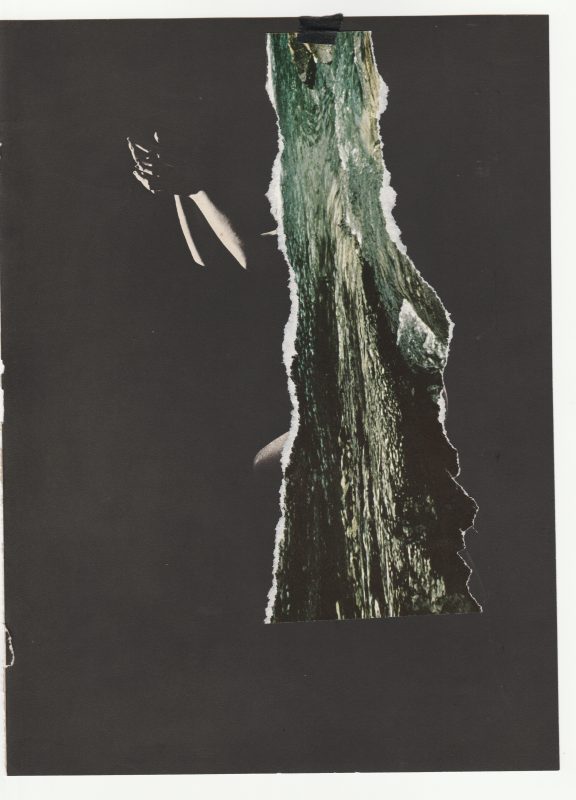

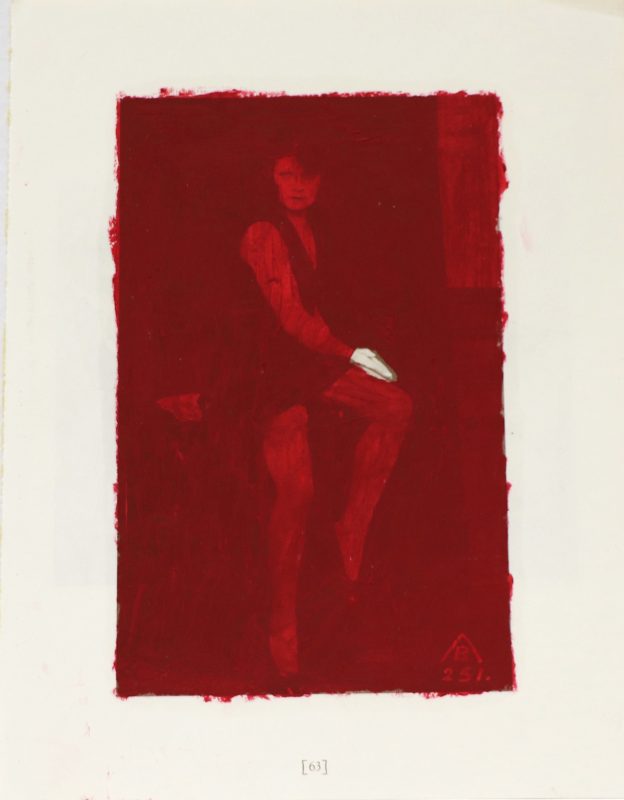

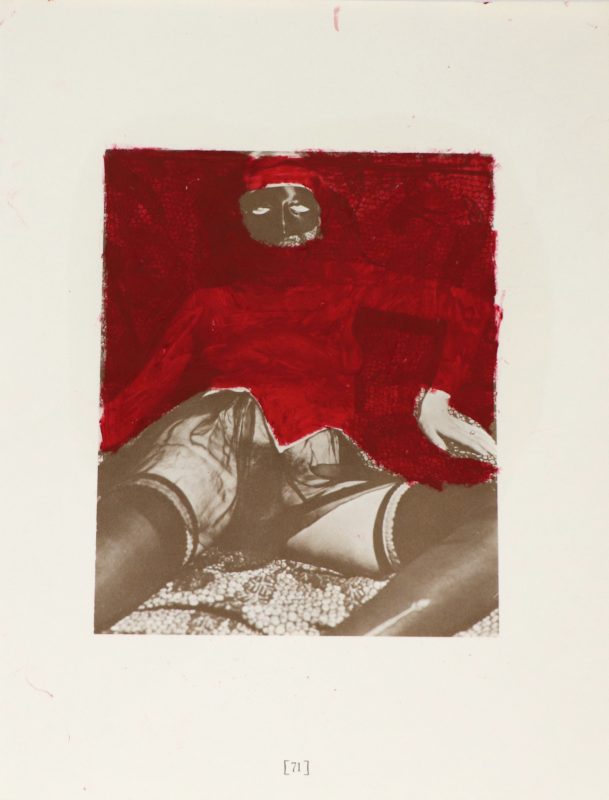

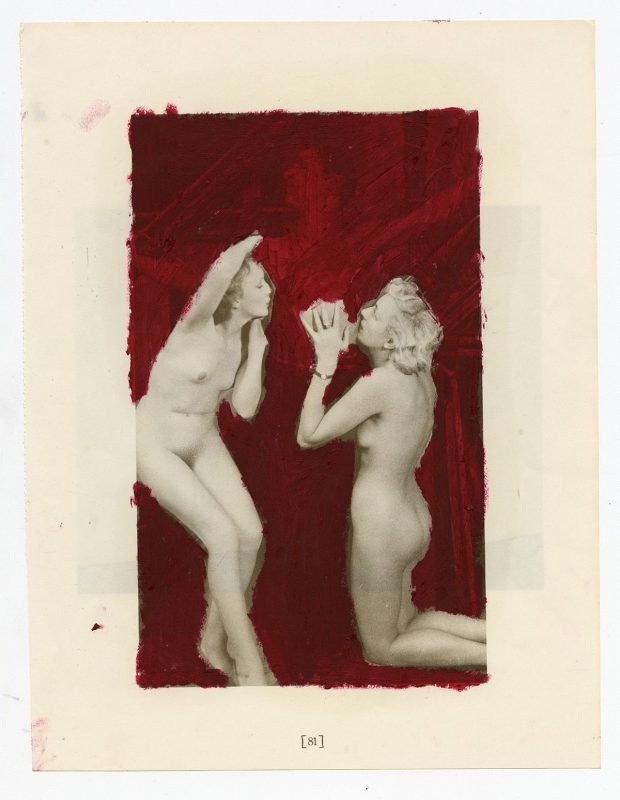

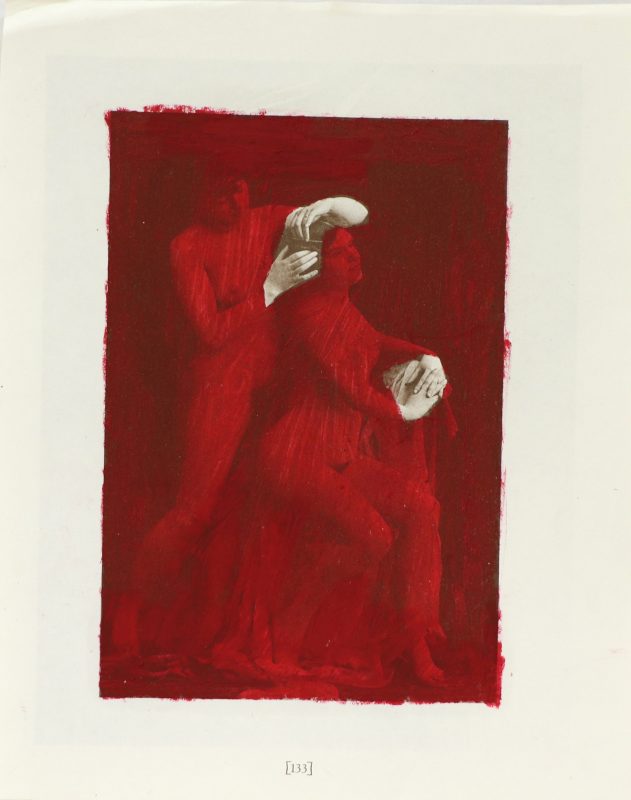

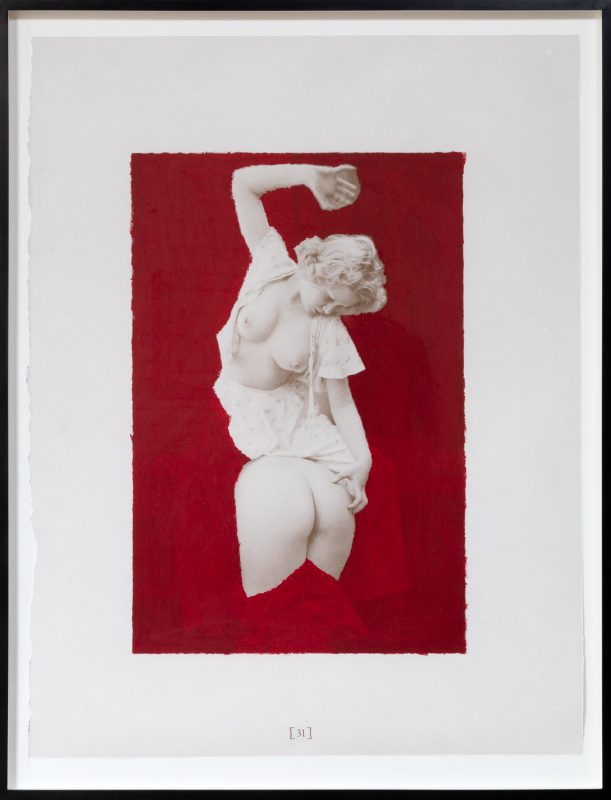

The Discrete Channel with Noise begins with a circulating image. A small archive of 36 photographs collected by the artist – and coincidentally used in another work, The Entropy Pendulum and OutPut (2015) – formed the basis from which Strand’s husband selected 10 images which make up the final series. Across a number of Skype calls, between the artist’s home in Brighton and her temporary studio in Paris, each original photograph, cast into 2928 individual squares over a 48×61 grid, was communicated verbally using an agreed greyscale number code, with the artist painting each square onto large sheets of paper to recreate the images. Inverting Moholy-Nagy’s process, Strand is not the transmitter but the receiver; a receiver of chance and happenstance, she embraces and absorbs the accidental. Here, in what is in effect a human machine, Strand cedes control of selection – to test his method, Shannon identified that any ‘actual message is one selected from a set of possible messages’ so that the engineer must devise a system encompassing all possible messages – Strand works only with the information provided to her, which she must receive and transcode. In a playful take on the rise of video calling, the image is withheld, and described only across the call. What results are images that are recognisably photographic, lossy to our eyes, and bearing witness to moments of error or noise.

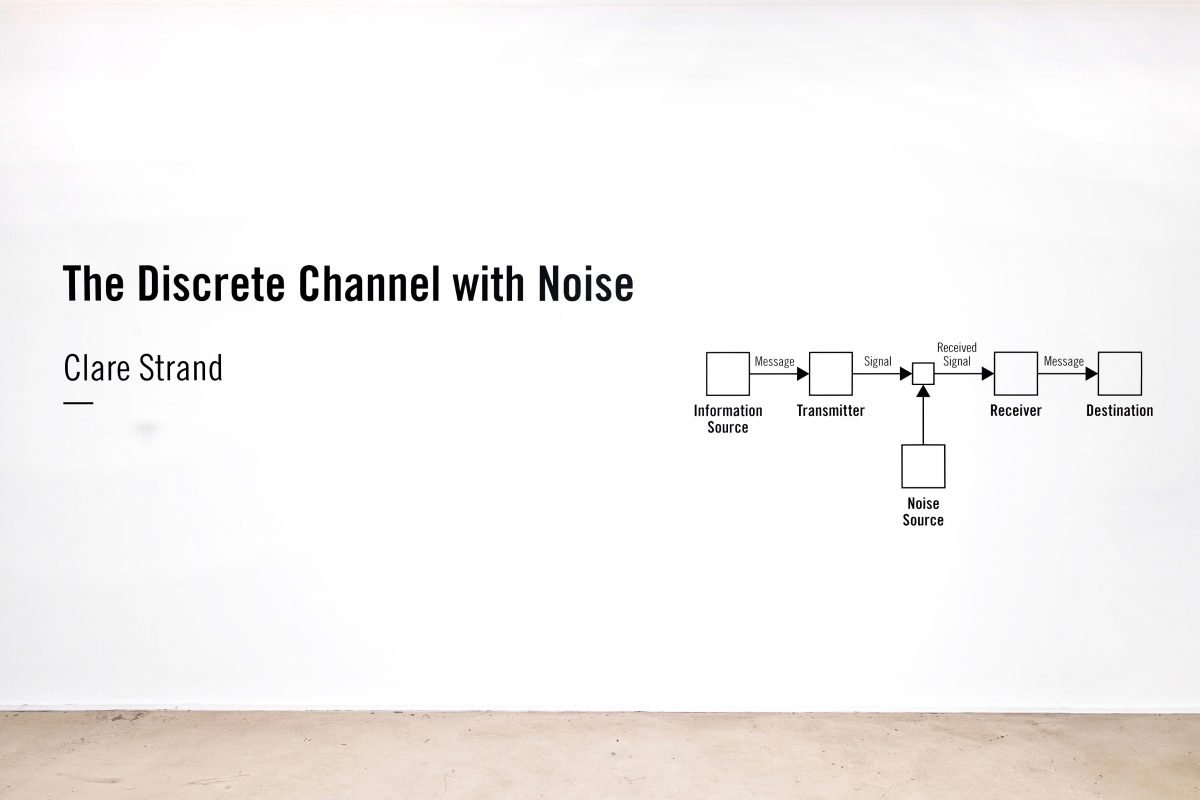

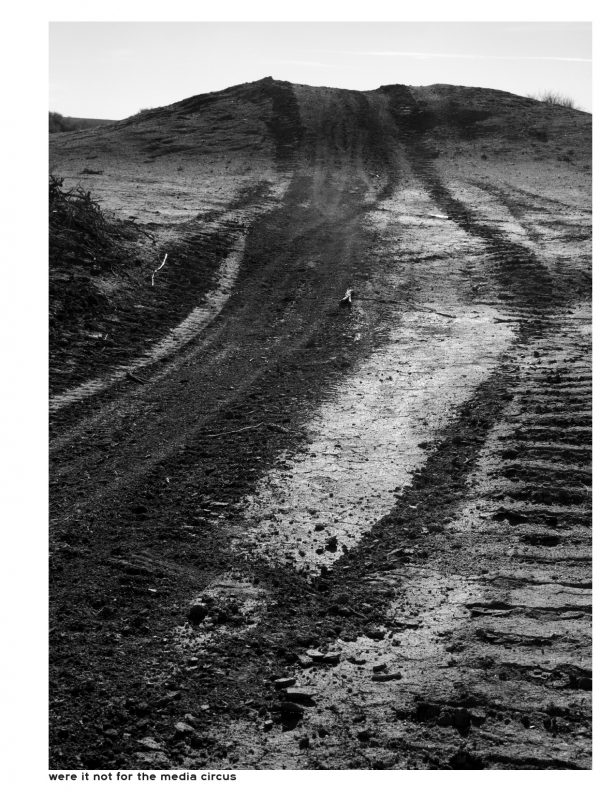

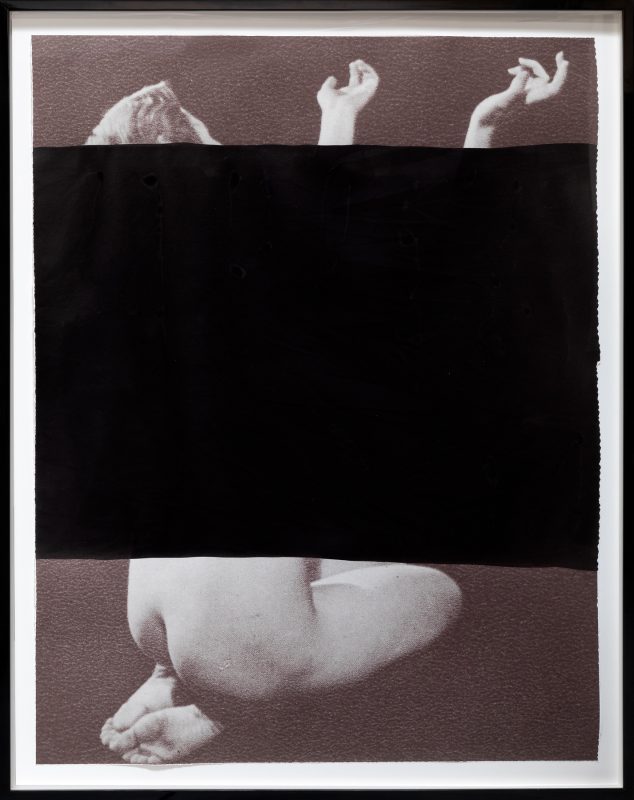

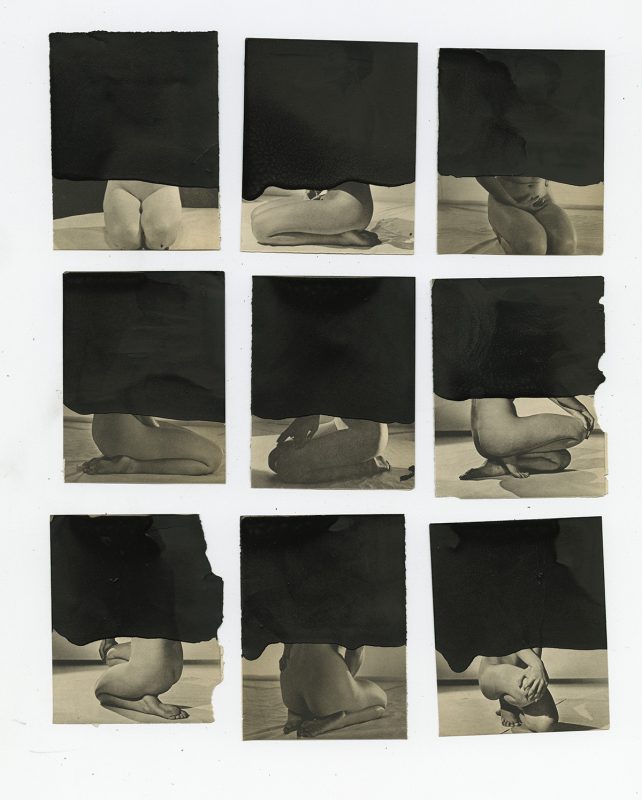

Across the series, we can recognise portraits and details, though the images – the precision and accuracy that we have come to expect – remains elusive. Our attention shifts repeatedly from pictorial subject to process and object. In a contrast to Moholy-Nagy’s Telephone Pictures, Strand’s hand is readily apparent on the surface of each painted image. Each square is painted, but brush marks and overlaps pepper the surface of the picture. In her first exhibition of The Discrete Channel with Noise, at Centre Photographique d’Ile-de-France in Paris in 2018, Strand displayed, on a wall opposing the resulting Algorithmic Paintings, all aspects of the work’s process, including the original images and tubs containing 10 tones of paint in greyscale, as well as brushes to further emphasise the handmade construction of the project. On the first wall of the exhibition, Shannon’s diagram of ‘a general communication system’ is reproduced. From ‘Information Source’ to ‘Transmitter’, the diagram moves towards the ‘Receiver’ and its ‘Destination’. In its centre is a ‘Noise Source’. If Strand’s images show us the photograph compressed into its smallest parts, shaped into units, pieced together in correct and incorrect orders, the noise is unquestionably human. Hers is a deliberately manual adoption of Shannon’s method, stripped back to its basic principles. With the originary images, here each captioned as an Information Source, exhibited opposite to the resulting Algorithmic Painting – we are pointedly placed in the centre, a human in the machine. We do the work of recognising the image, and see its transmission, including its errors. Perhaps we can identify ourselves in fact as the central square in Shannon’s diagram, as the ‘Noise Source’. Are we reliable narrators, reflecting upon what we broadcast, and verifying the information we transmit? We might reflect on communication not as mechanical. A key concern of Strand’s is the culture of misdirection, snooping, and miscommunication that our contemporary technologies enable. From the Cambridge Analytica scandal to the ongoing and overt misinformation spread by Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, we are willing operators in a system that we know is distorting our messages, one that has also rendered us uncritical receivers at the very same time. Indeed, if the critique of the photograph’s claim to truth has led to transformations in how we conceive of the image, Strand’s project shows this to be vital also in not just the image or the text, but in the form, or channel, that we privilege. As John Roberts has pointed out in his study on photography in the present, Photography and Its Violations (2014), the human qualification that all forms of speech require in testimony, the embodying call ‘believe me’, should be applied to the photograph and to its delivery. We must return it to the object of a human producer, and show a willingness to put ourselves forward and become part of the image and its claims. We must not only show ourselves, we must find alternate systems for verification as recipients. If recent elections have told us anything, it is in the incredible influence that a partisan media can possess. The forms of broadcasting and transmission are not non-human. We are the human agents of these technological forms: we are its transmitters, noise sources, and receivers. We have the capacity to determine how information travels, and to whom it travels. ♦

The Discrete Channel with Noise is on display as part of the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2020 at The Photographers’ Gallery, London from 21 February 2020, with the winner announced on 14 May 2020.

Images courtesy the artist. © Clare Strand

Installation images from Photographique d’Ile-de-France courtesy the artist and Centre Pompidou. © Aurélien Mole

—

Duncan Wooldridge is an artist, writer and Course Director of Photography at Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London. He writes regularly for Artforum, Art Monthly and Elephant. In 2011 he curated the exhibition Anti-Photography at Focal Point Gallery, in 2014 John Hilliard: Not Black and White, at Richard Saltoun Gallery, London, and in 2019 Moving The Image: Photography and its Actions.

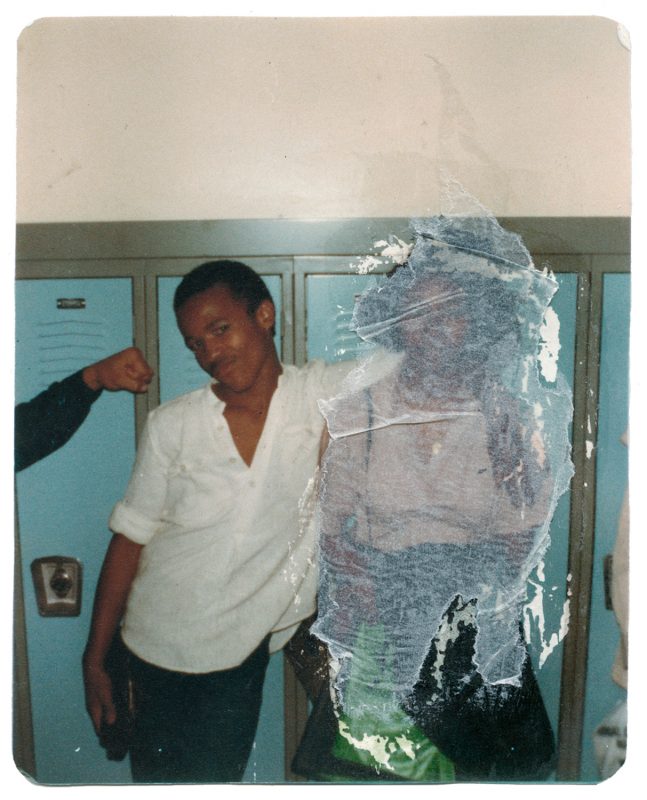

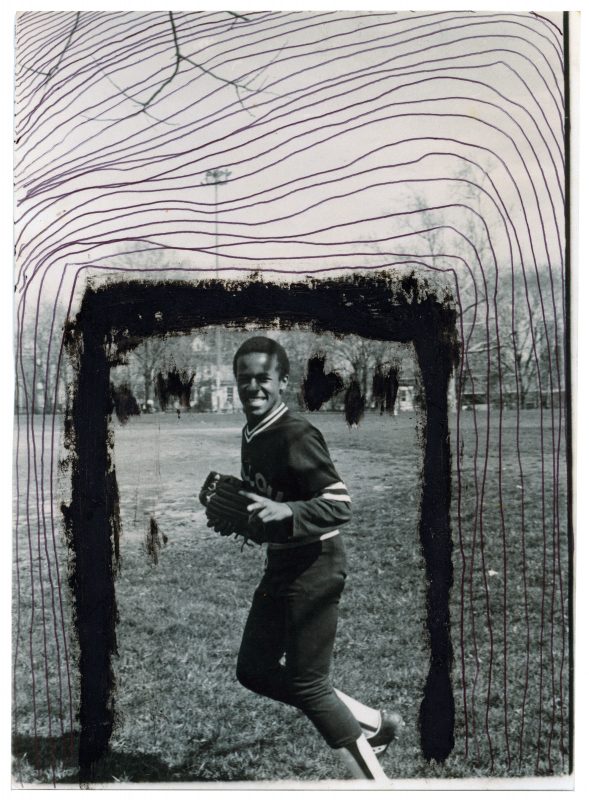

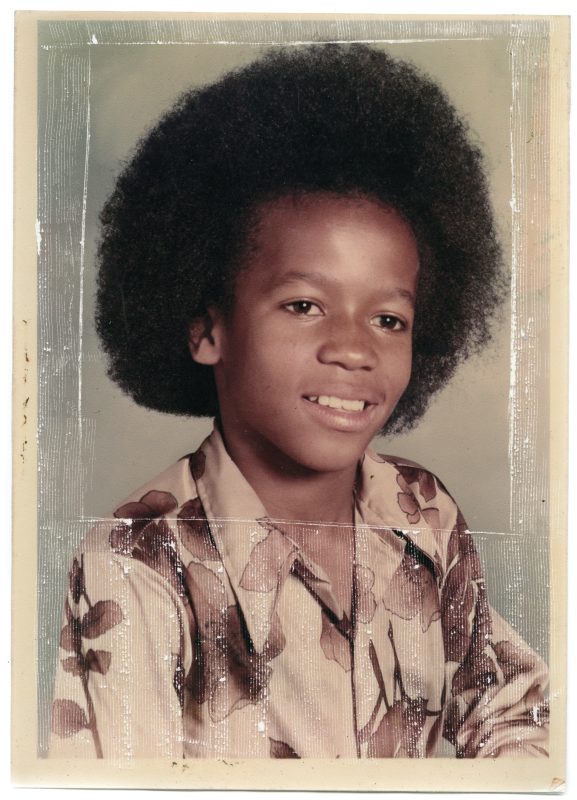

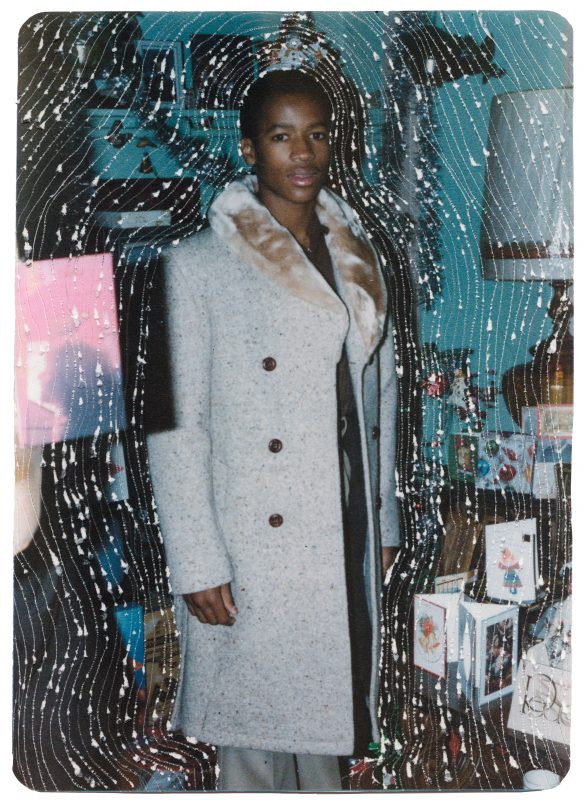

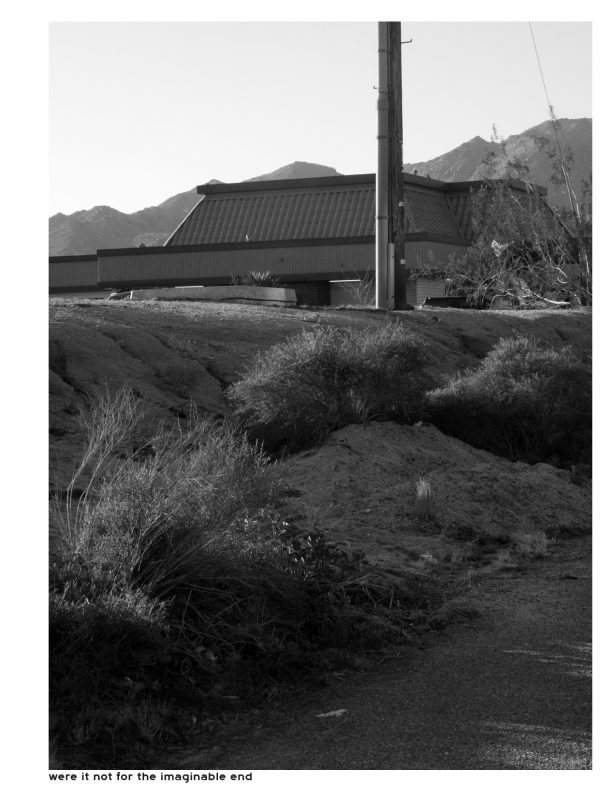

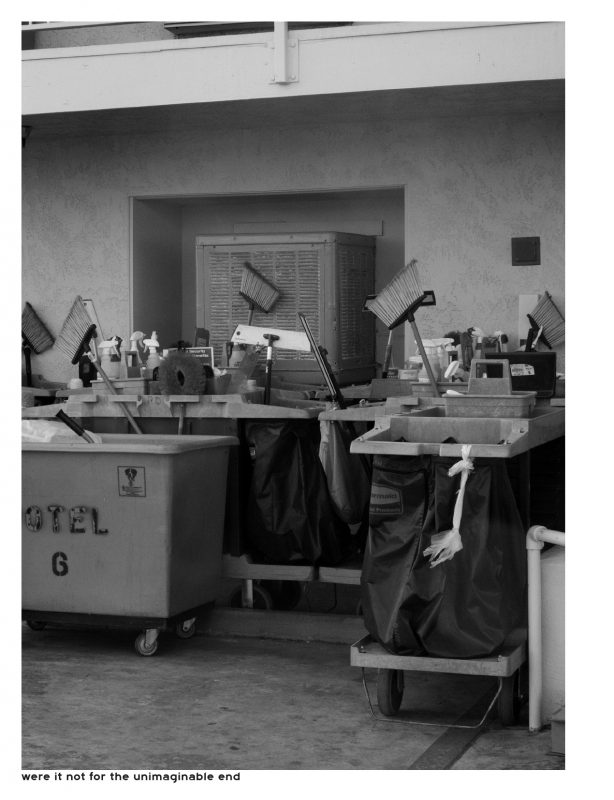

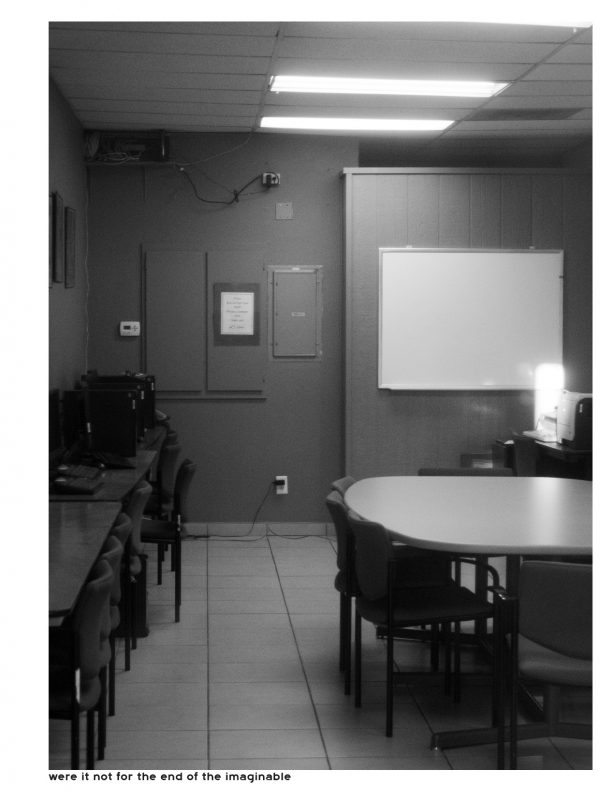

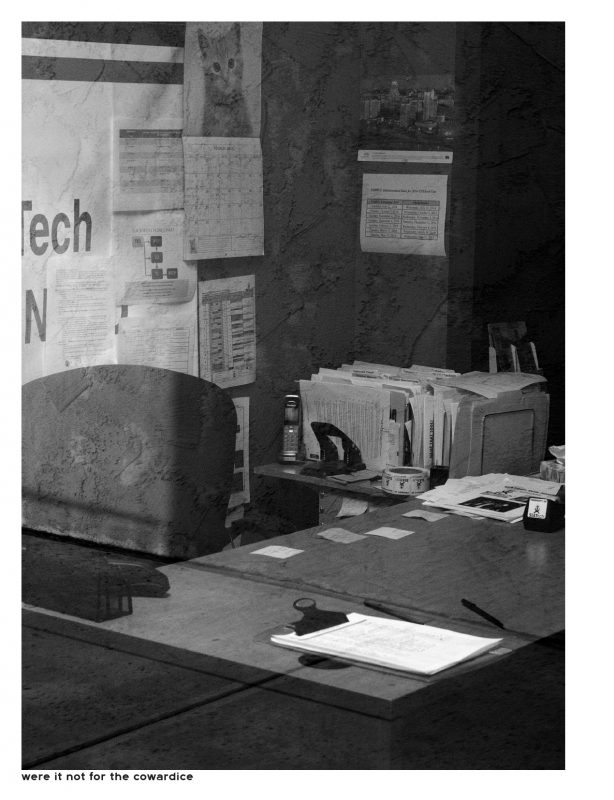

Captions:

1-Schematic diagram of a general communication system from A Mathematical Theory of Communication by Shannon and Weaver, published by Bell Systems (1949)

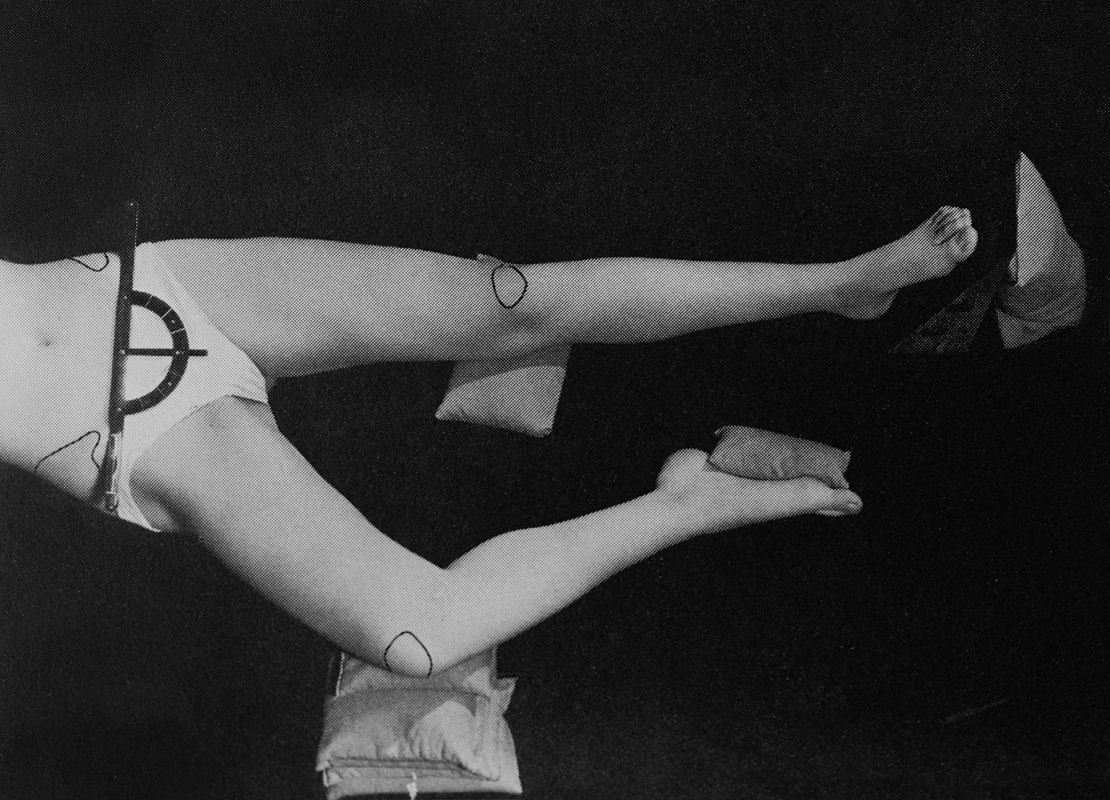

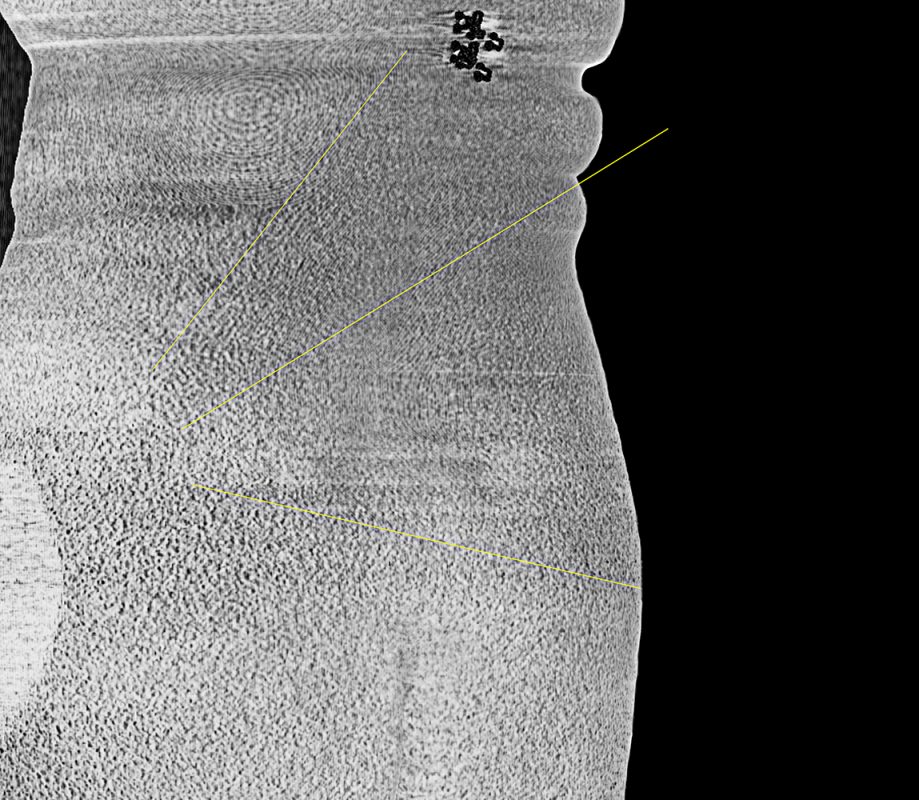

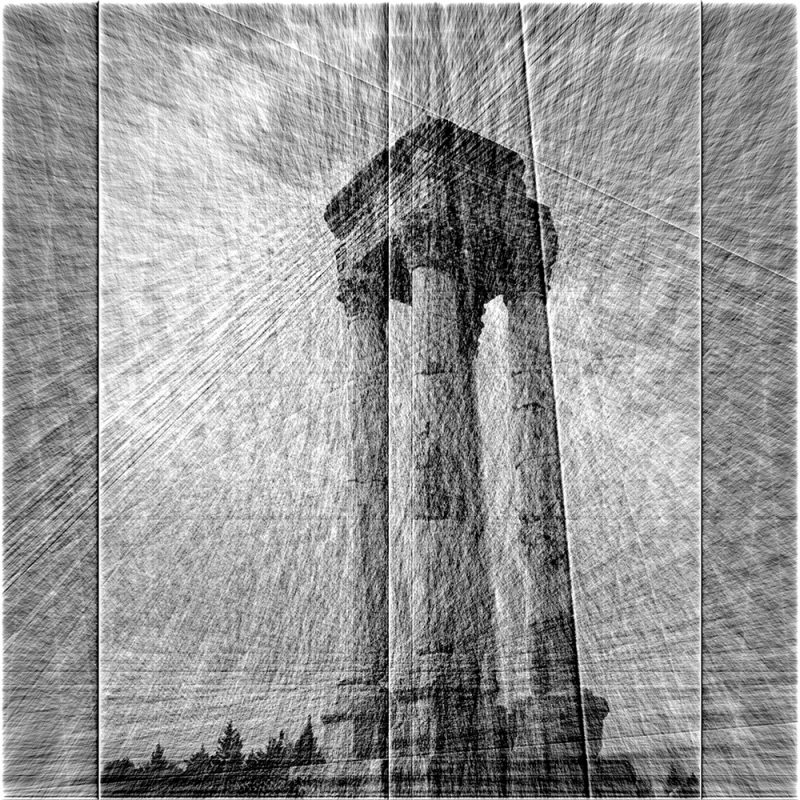

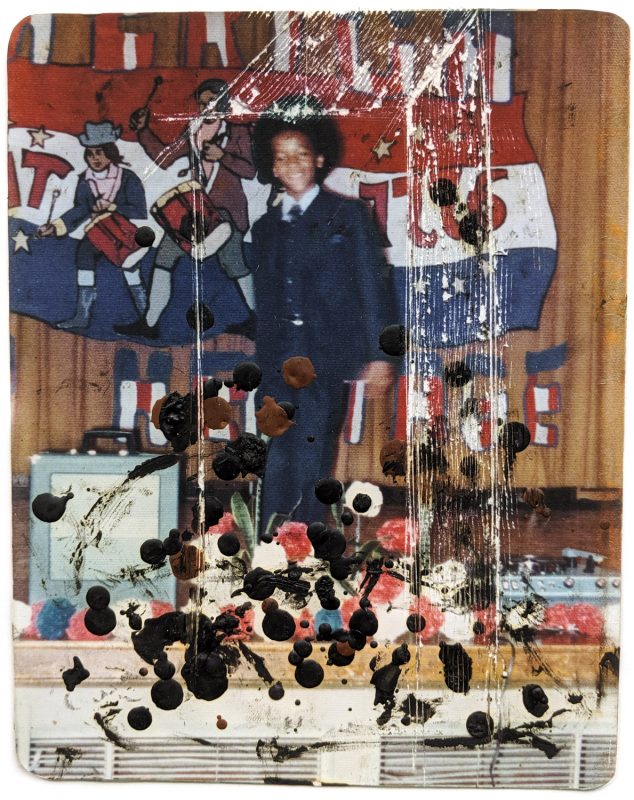

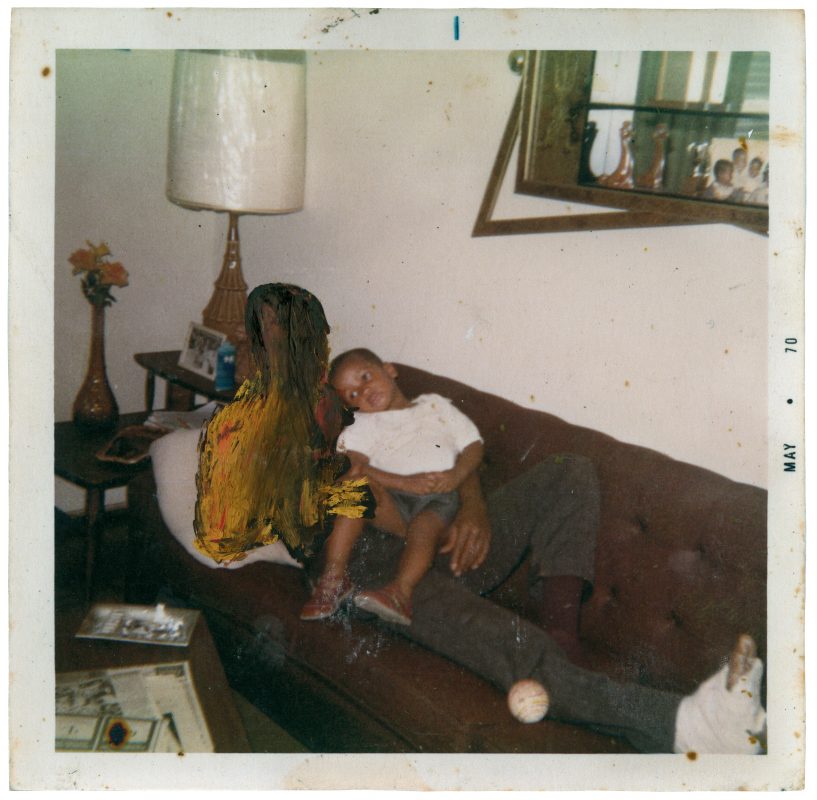

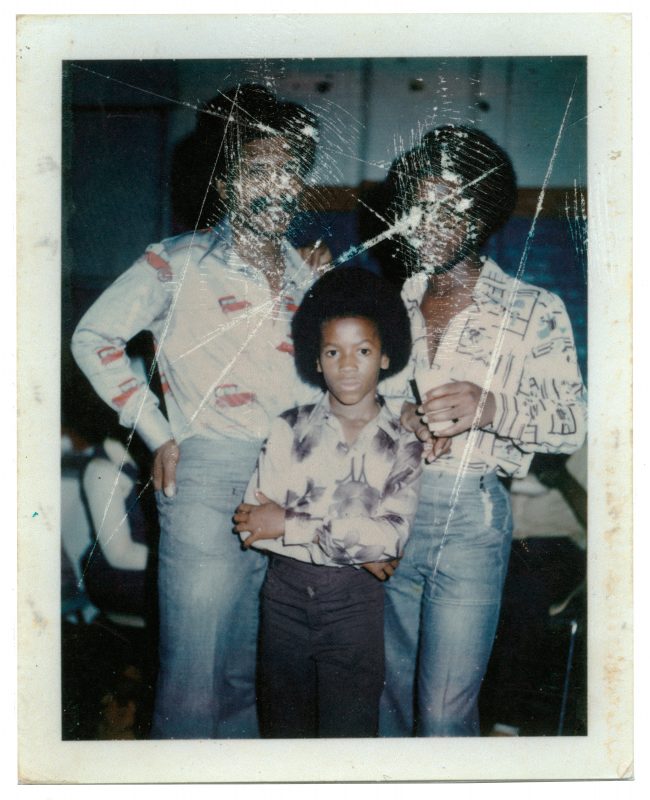

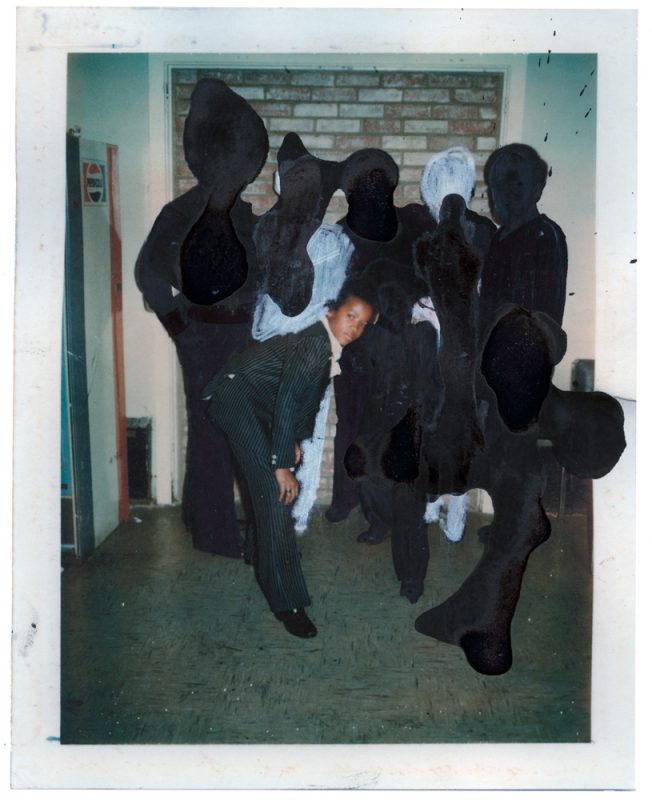

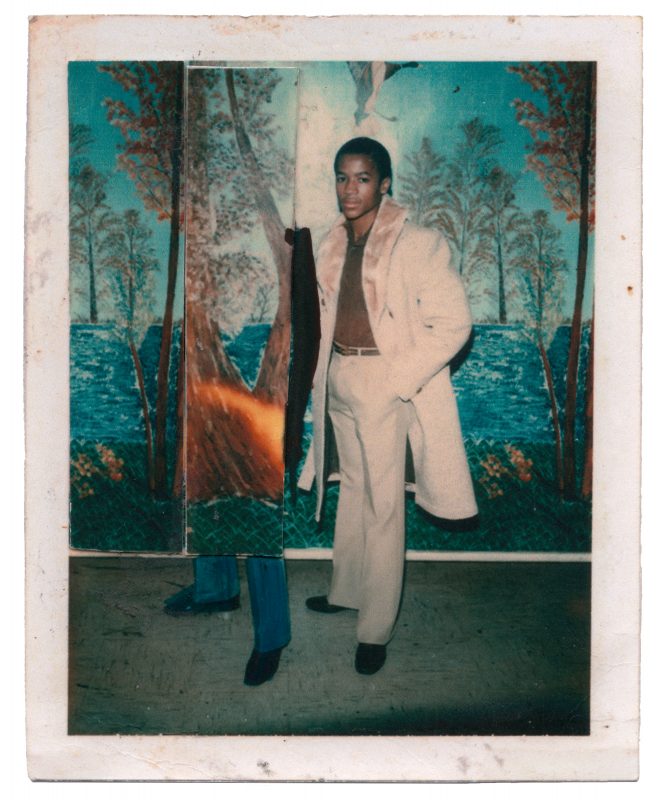

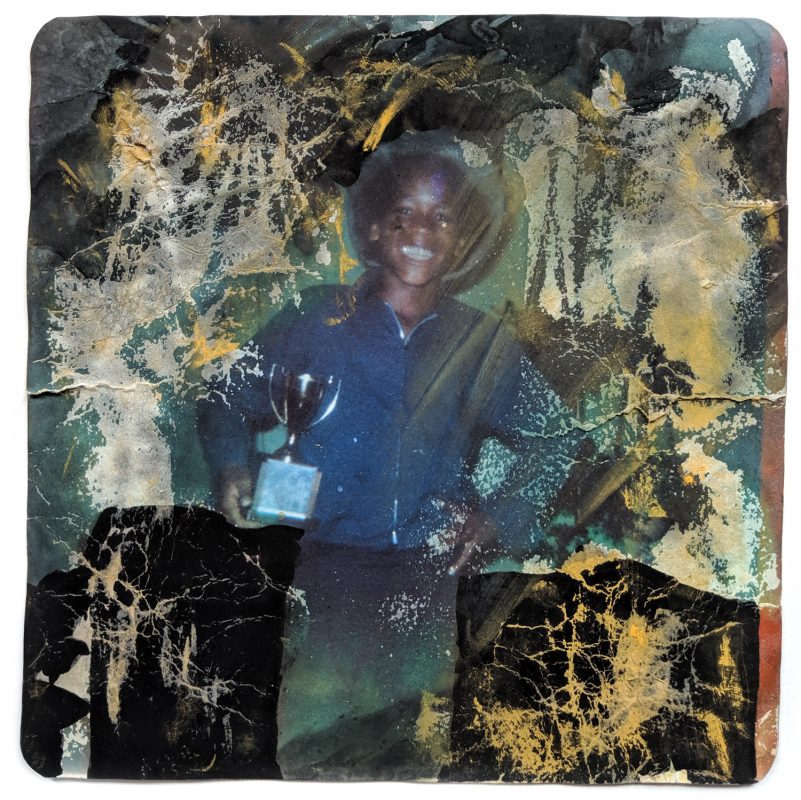

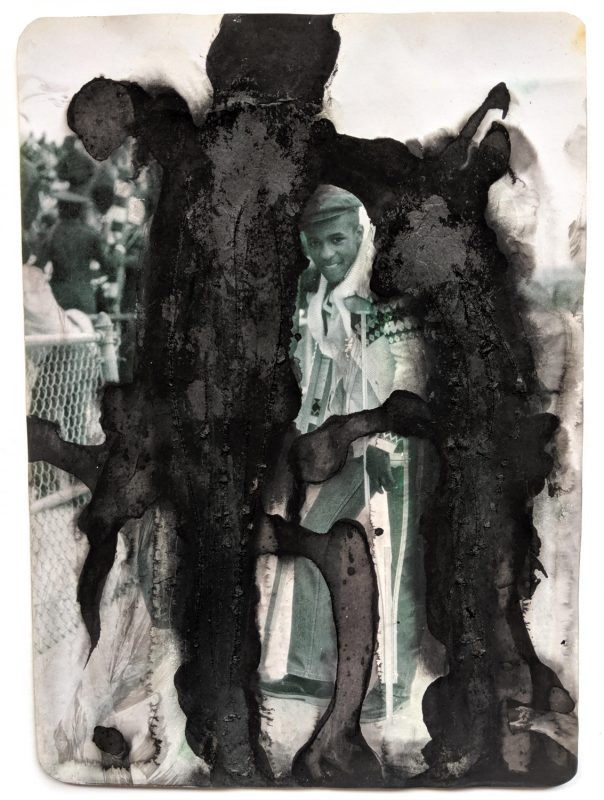

2-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Algorithmic Painting; Destination #3-8

3-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Algorithmic Painting; Destination #4-10 + The Discrete Channel with Noise: Information Source #4-10

4-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Algorithmic Painting; Destination #7

5-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Algorithmic Painting; Destination #4

6-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Paint Brushes and Paint Pots

7-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Paint Pots 1-10

8-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Paint Pots (Detail)

9-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Paint Brushes (Detail)

10-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Paint Brushes (Detail)

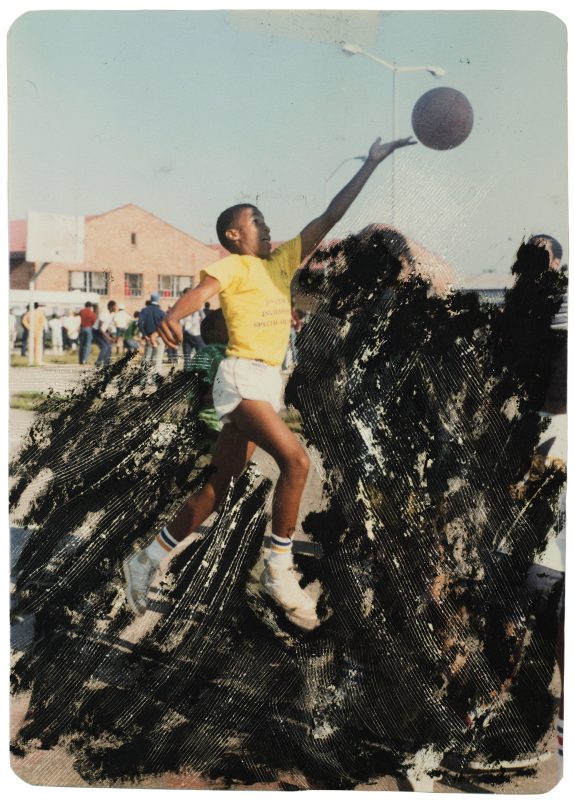

11-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Information Source #4-10

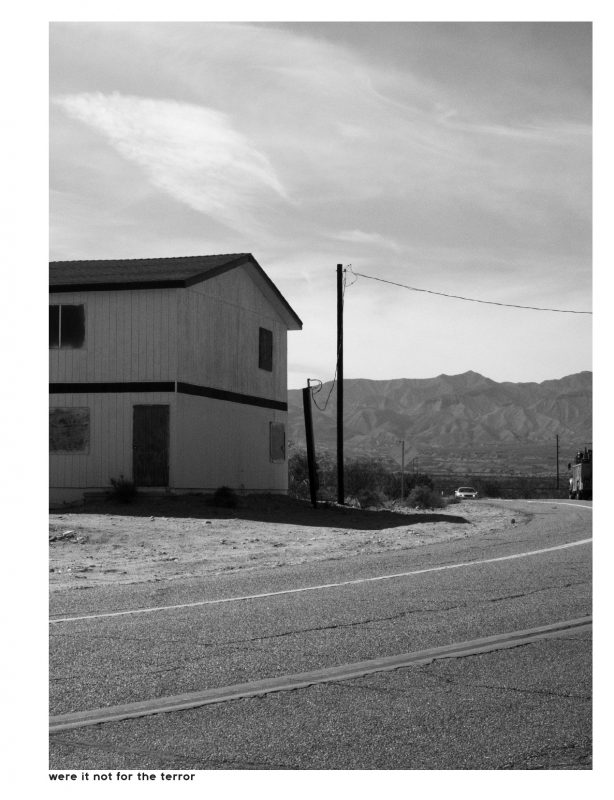

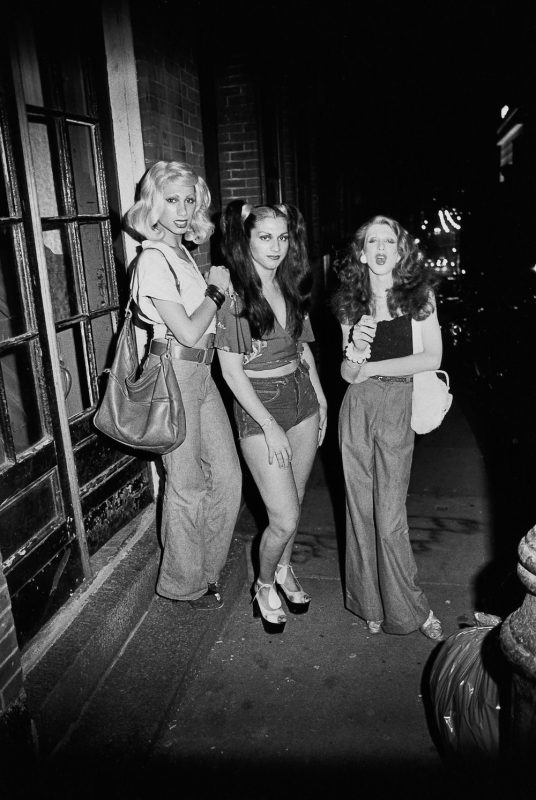

12-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Information Source #6

13-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Information Source #3

14-Clare Strand, The Discrete Channel with Noise: Information Source #7