Sheida Soleimani

Birds of Passage

Exhibition review by Gem Fletcher

Gem Fletcher visits the latest exhibition at Denny Gallery, New York, Sheida Soleimani: Birds of Passage, an ongoing collaborative project which sees the artist work with her parents Mâmân and Bâbâ – two Iranian pro-democracy activists and refugees – to translate their traumatic experiences of political exile leaving Iran in the 1980s via densely layered images that half-document, half-mythologise family lore.

Gem Fletcher | Exhibition review | 5 Oct 2023

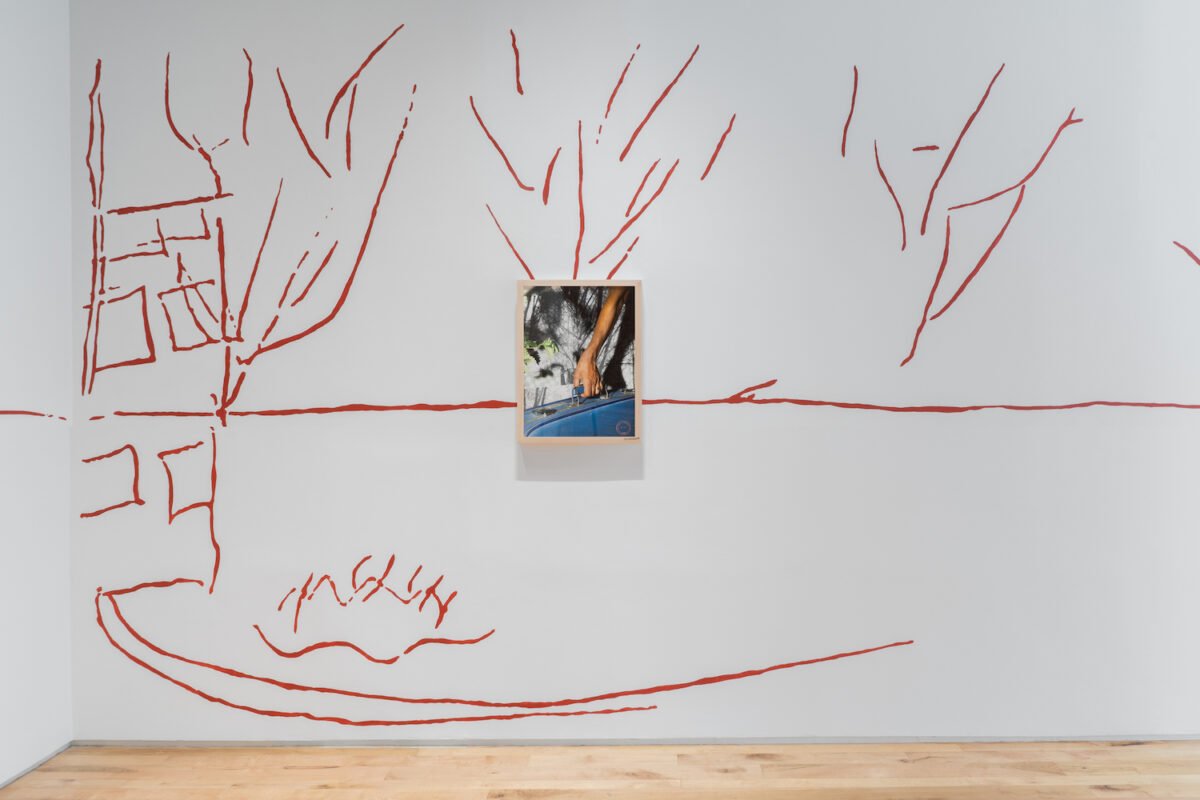

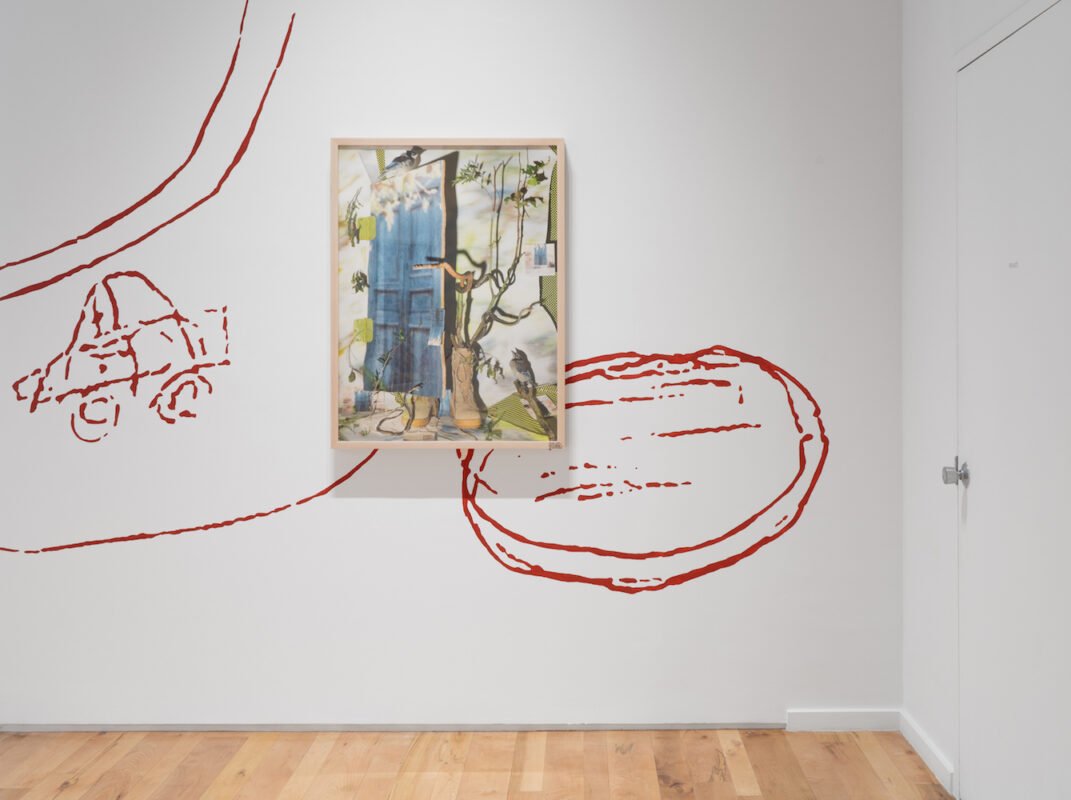

Spring 2023: I am at Edel Assanti, London, where a hand-drawn map, embedded with photographs, covers every inch of the gallery’s walls as part of Sheida Soleimani’s ambitious series Ghostwriter. The interplay between image and sketch, combined with the map’s lack of perspective, creates a subtle sensation that the ground is moving beneath my feet. The feeling is overwhelming, unexpected and seemingly involuntary as the map pulls me in. It recalls the city-bending scene in Inception (2010) when Ariadne (played by Elliot Page) rebuilds the landscape of a Parisian street with her imagination without being bound by the laws of physics. Whilst Solemaini’s map in Ghostwriter is more rudimentary – the frenetic and urgent blue mark-making feels more akin to something you might scribble privately on the back of a napkin for a friend – it is nevertheless effective in creating a disorientating spatial sensation that defies gravity.

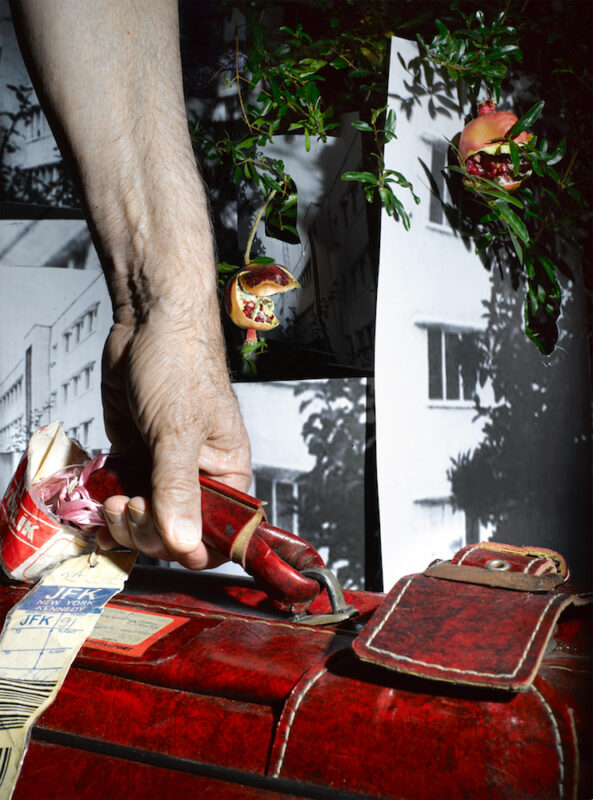

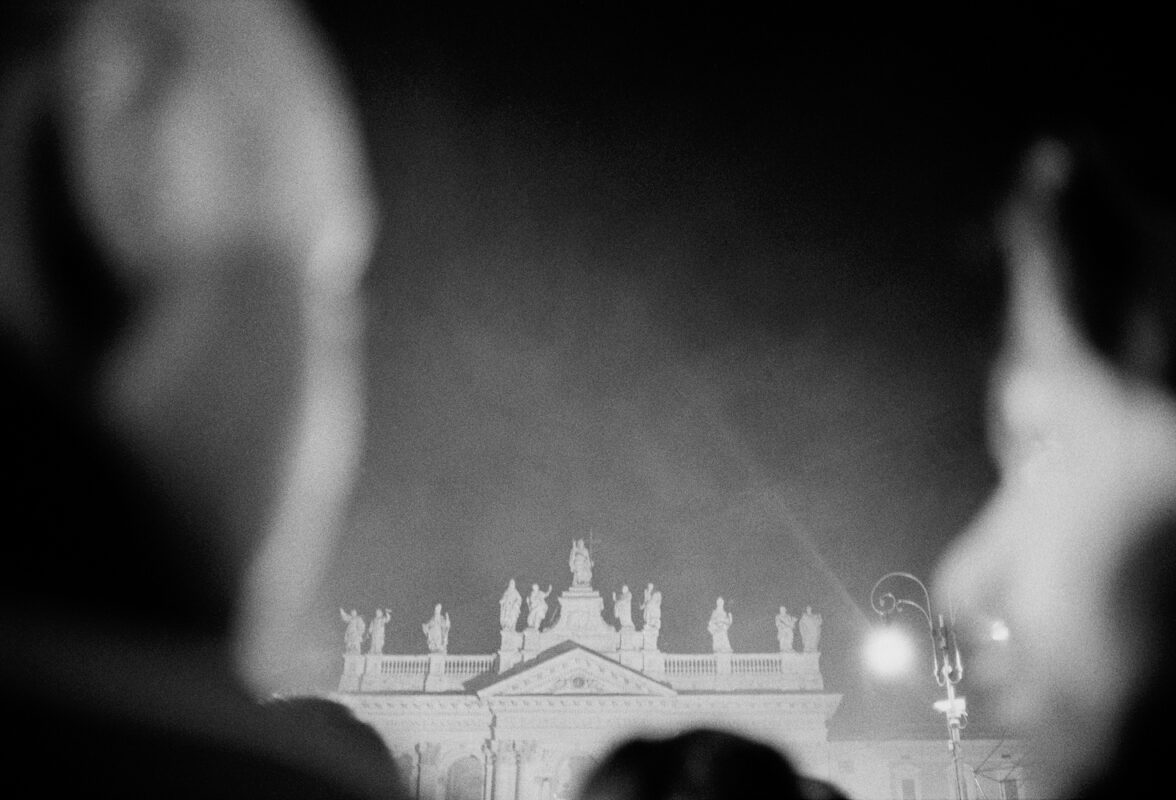

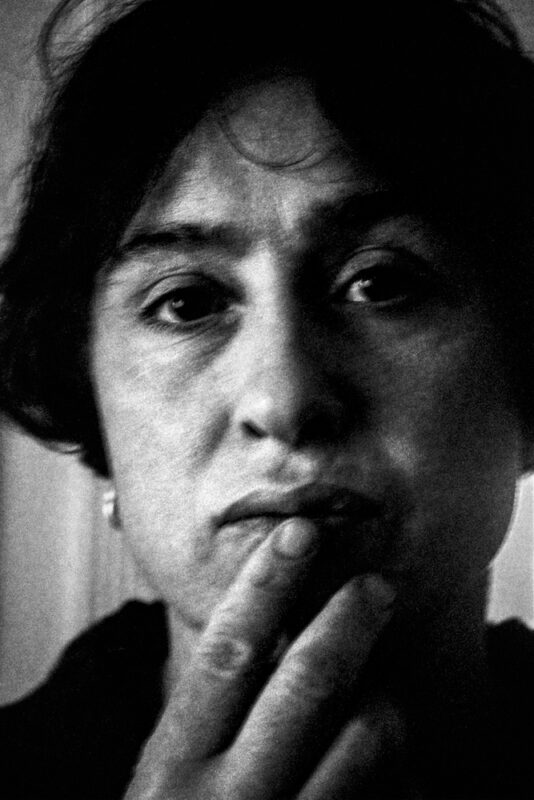

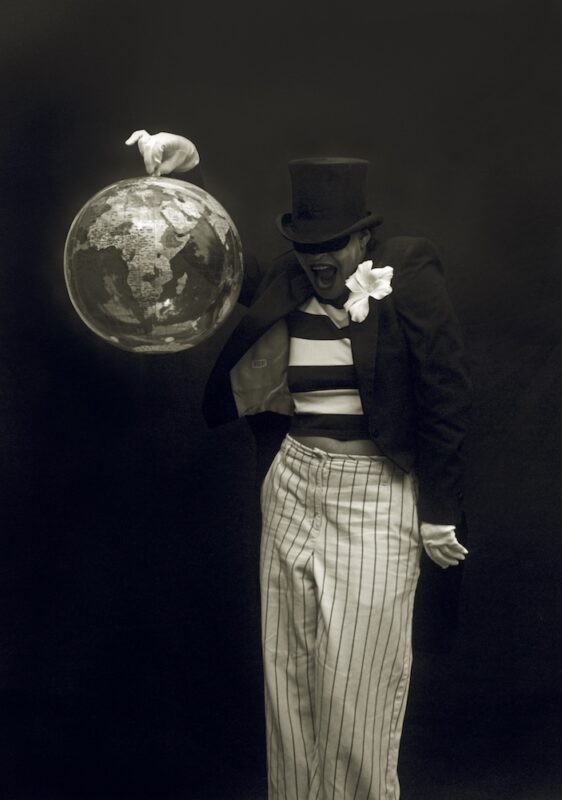

Experiential storytelling is the driving force of Ghostwriter. In the ongoing collaborative project, Soleimani works with her parents Mâmân and Bâbâ – two Iranian pro-democracy activists and refugees – to translate their traumatic experiences of political exile leaving Iran in the 1980s. The duo opposed both the Shah government and the Ayatollahs’ totalitarian regime. Bâbâ went into hiding as Iran began to tighten its response to political dissent before eventually fleeing on horseback. At the same time, Mâmân endured solitary confinement and worse before finally reconnecting with him in the US.

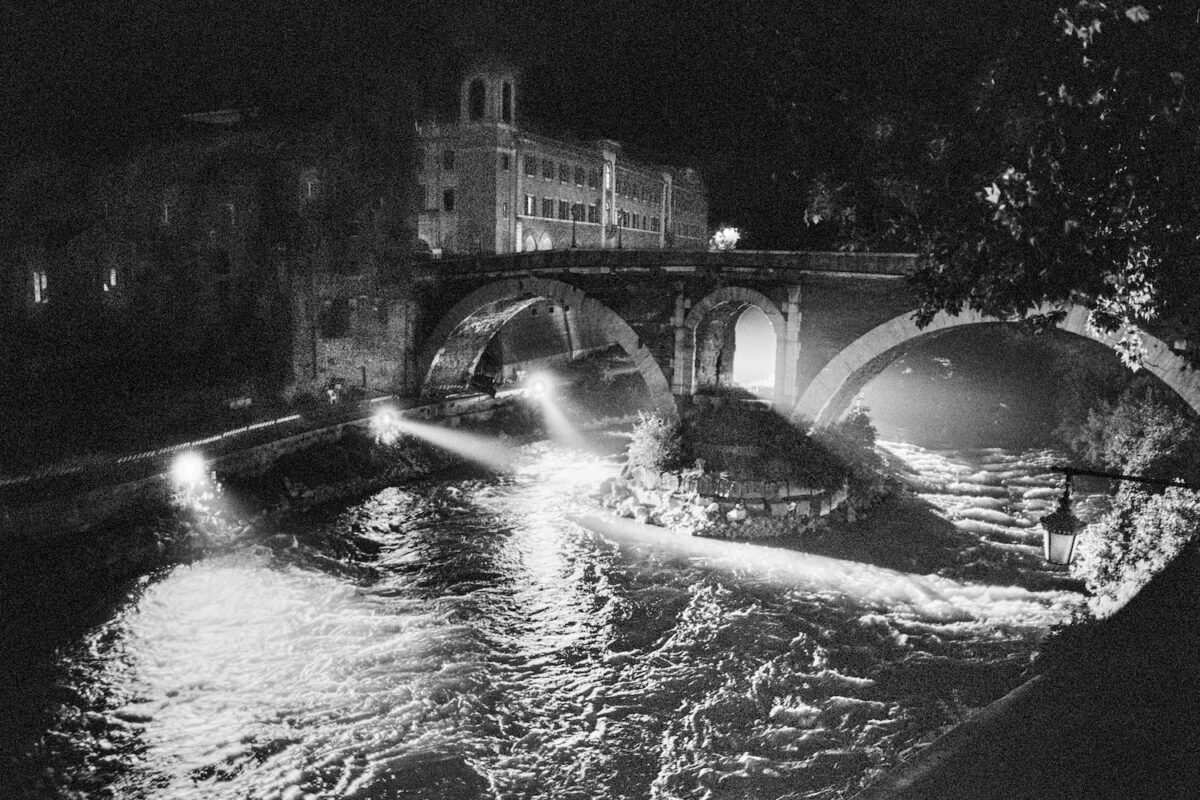

The map at Edel Assanti, drawn by Bâbâ, traces his escape route through Iran, coming over the Zagros mountains into Turkey. Situated within it are Soleimani’s photographic assemblages – densely layered images half-documenting, half-mythologising family lore—which act like map keys unlocking specific scenes and information about their stories. For Soleimani, the gallery is a portal, a theatre of ideas to engage with the complexity of surviving political exile.

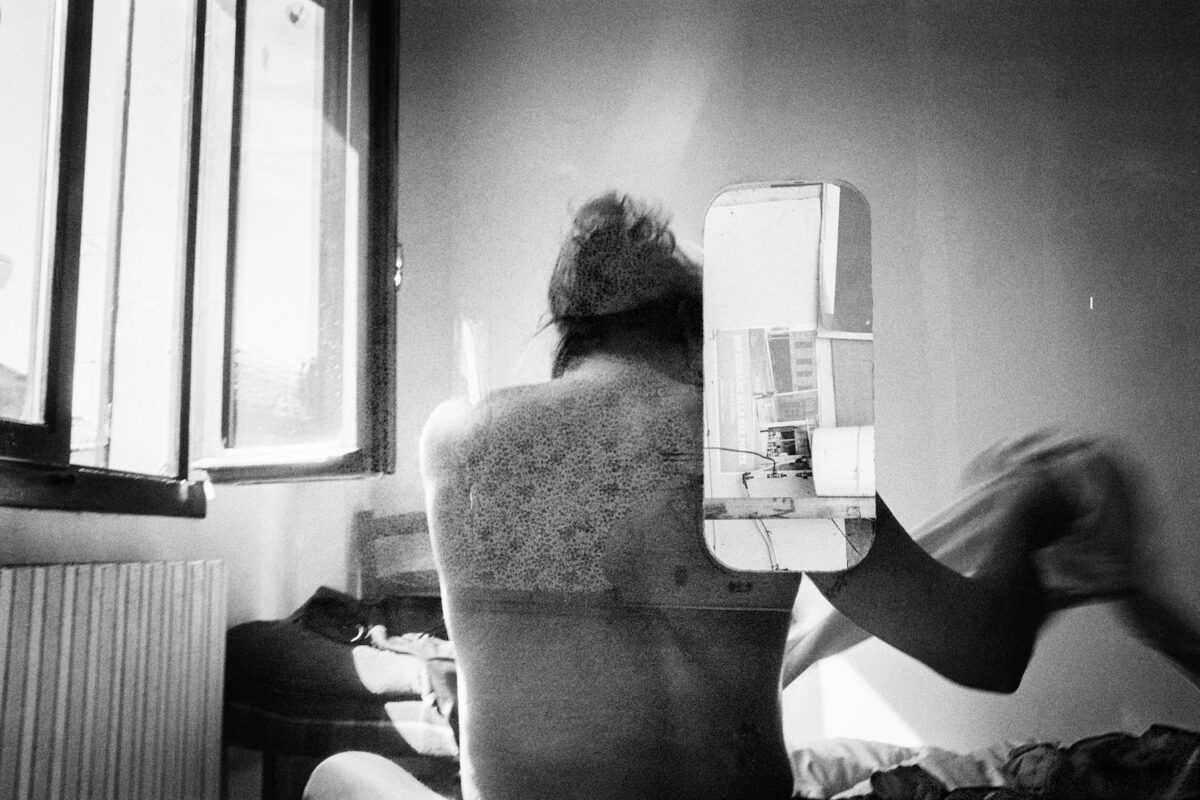

Autumn 2023: I am at Denny Gallery, New York, standing in Soleimani’s latest iteration of Ghostwriter, Birds of Passage. On this occasion, the map doesn’t pull you in but instead drops you, like Google Street View, into Mâmân’s detailed sketch of Namazi Hospital in Shiraz, Iran. The location is significant. It’s not only the site in which the couple first met in 1975 and their place of work (Bâbâ was training to be a doctor and Mâmân a nurse), but was also a site of resistance during the revolution. As surveillance increased for activists, Mâmân and Bâbâ began holding dissenter meetings in the operating theatre to avoid detection.

Birds of Passage is the third installation in the Ghostwriter continuum. Each chapter jumps through time, weaving together emotional truths with larger socio-political issues in a labyrinthine journey. The first chapter, On the Wall, presented in Providence College Galleries in 2022, was set on a map of the courtyard of Mâmân’s childhood home, where Bâbâ went into hiding for many years. In contrast to the second chapter at Edel Asanti, which offered a macro view of her parents’ lives predominantly focused on Bâbâ’s escape, Soleimani utilises the smaller square footage at Denny Gallery to present a concise micro-chapter on her mother’s psychological experience at the hospital and later in solitary confinement before her escape in 1976.

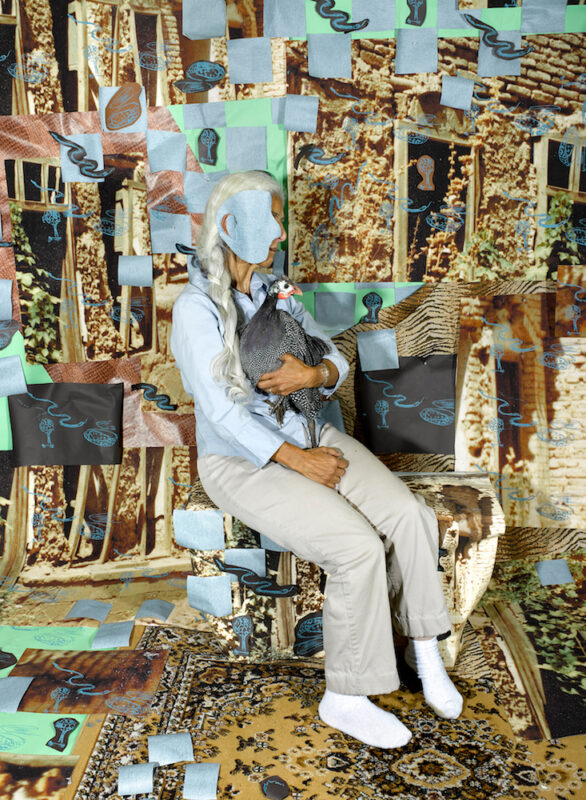

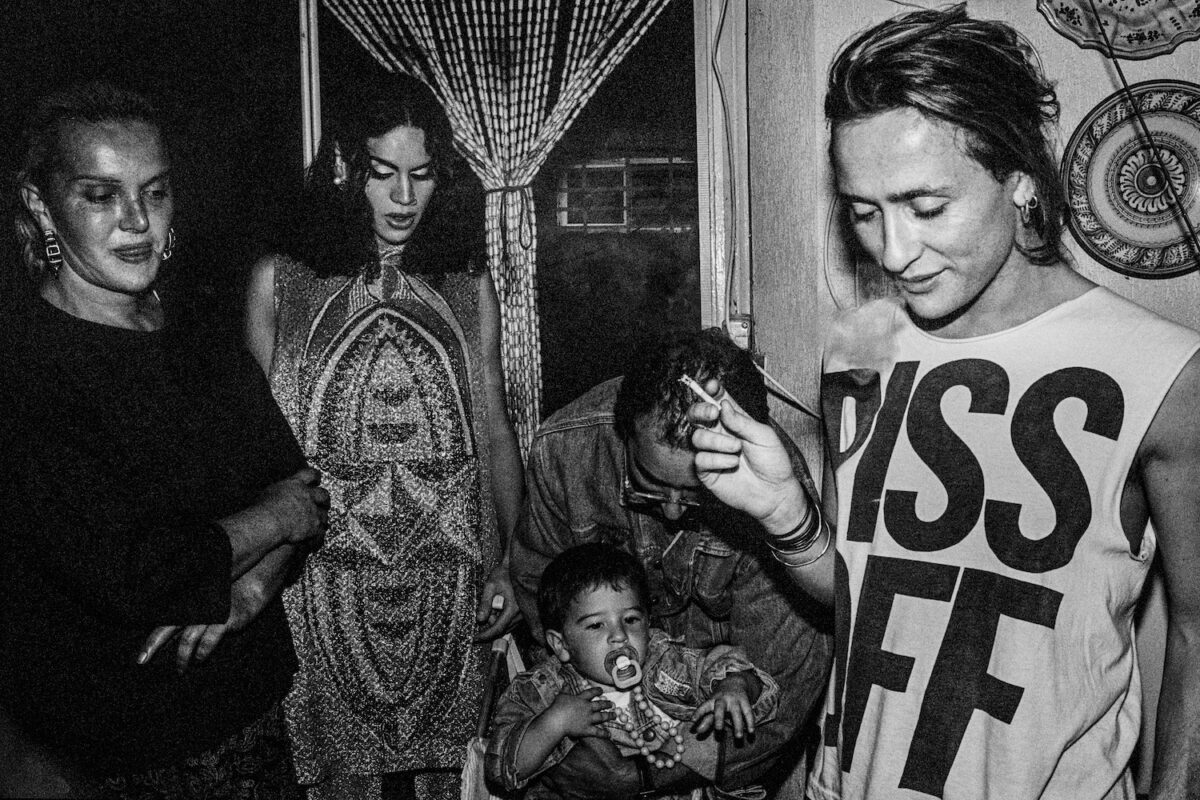

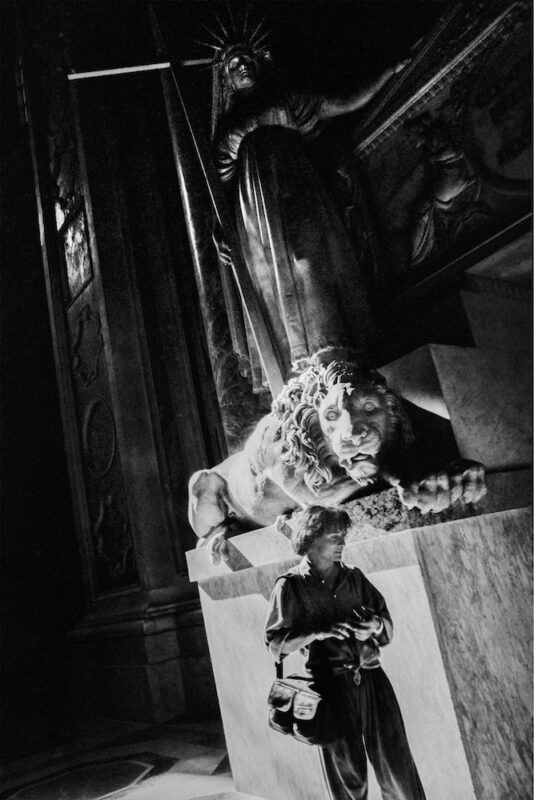

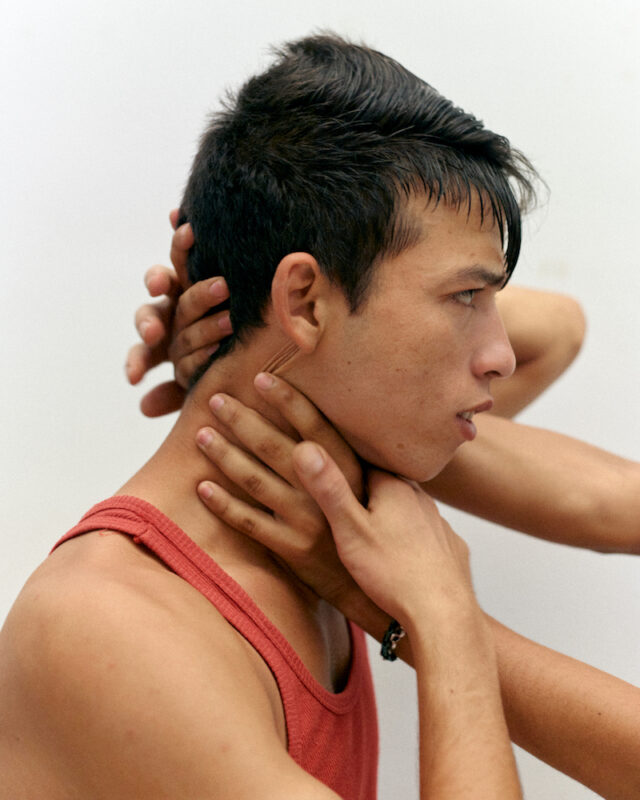

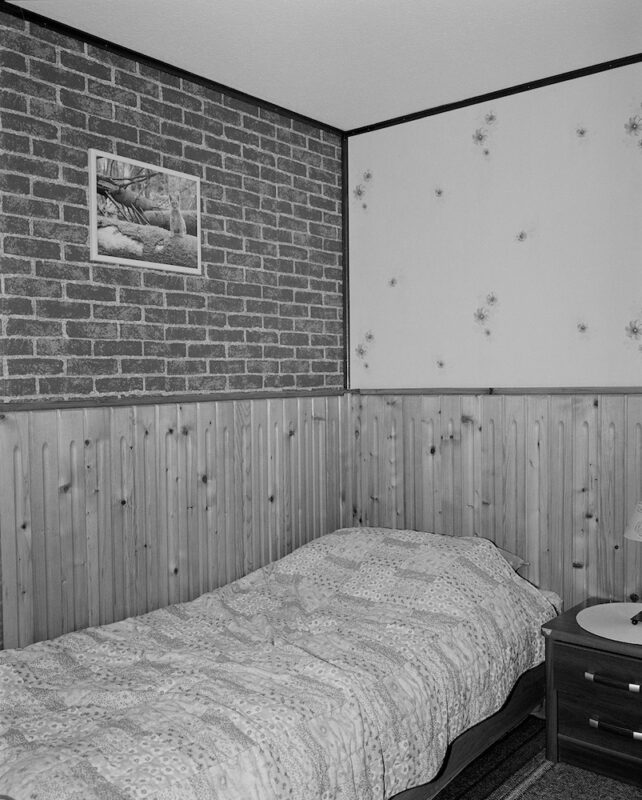

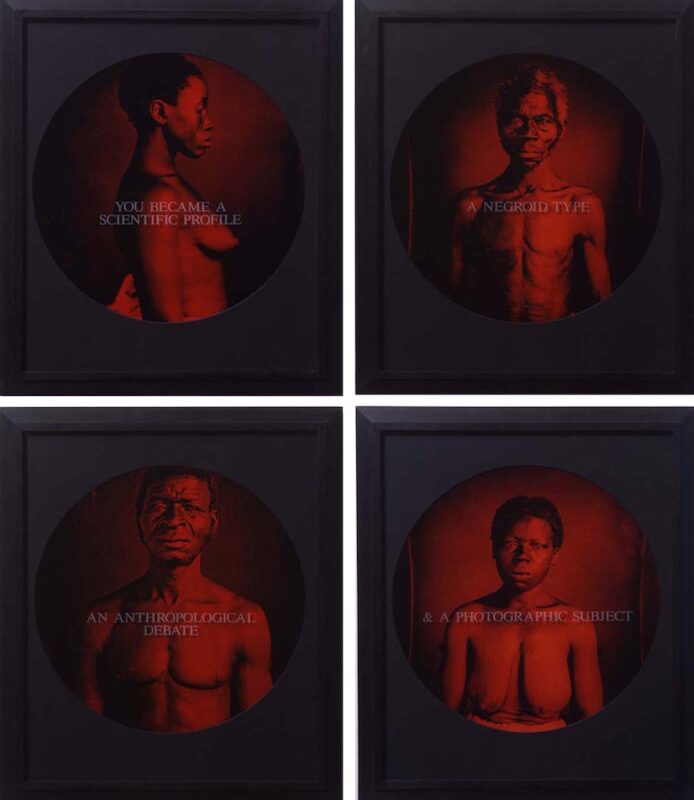

Like all the images in Ghostwriter, the complex stagecraft in Birds of Passage is informed by Dada collage, magical realist texts, political puppetry, propaganda poster design and feminist craft practices. Soleimani chops, collages and sculpts images to set the scene in her theatrical three-dimensional tableau. Objects, drawings, prints and fabric, sourced and crafted by the trio, are vessels for the story, set against a flaunting of fantastical shapes, colours and textures that create unique visual codes, networking the different chapters together.

One of the most significant codes in the series is taken from an ancient Persian game of Snakes and Ladders. The grid – which sometimes appears only subtly as a motif in the background and other times dominates the entire narrative of the image – alludes to the games immigrants are forced to play to survive as well as the elements of chance, risk and reward involved in the process of her parents’ journey. Soleimani plays with these contractions to build atmosphere and tension, shifting between beauty and peril, the alluring and the unnerving, holding us in limbo.

Ghostwriter is the first time Soleimani has turned the camera inwards. For the last decade, the artist’s practice has centred on geopolitics in the SWANA region, focusing on human rights violations and how governments fail to provide for their people. Now, we see the artist explore these themes through a personal lens in an attempt to retrieve, index and preserve her family’s story whilst examining the consequences of political systems reducing citizens to “abstractions”.

Time is not always linear in Ghostwriter as the artist grapples with how these stories have been told throughout her life. Since Soleimani was an infant, her parents, who didn’t believe in therapy, used storytelling to manage their PTSD and metabolise their traumatic displacement. At first, their experiences were shaped into a kind of autofiction – retold through protagonists like Mr Jones and his dog Bill over tea, on long car journeys and at bedtime – but as Soleimani and her sister got older, the stories became less censored and more matter-of-fact. “My parents didn’t want me to grow up and think of the world as an idyllic place,” she says. “They wanted me to know the truth.”

A commitment to ‘deep listening’, coined by the late American avant-garde composer and scholar Pauline Oliveros, shapes Soleimani’s life and practice. Oliveros distinguished hearing and listening – the latter a corporal experience that involves an acute awareness of the external and internal, spoken and unspoken, whilst paying attention to the multiple realities at play. Deep Listening embodies the trio’s co-creation process in Ghostwriter. Together, they patchwork different perspectives, memories and emotions from their collective past, dismissing the notion of singular truth and instead holding space for how trauma and the passing of time allow for new modes of (mis)interpretation.

Despite the shielded identity of her protagonists to limit the threat of ongoing persecution, there is a relational quality born from this work and how Soleimani unfolds the intimate geography of their lives. We become invested in them and their story. In theory, Ghostwriter’s biggest threat is becoming sentimental, a saccharine ode to the artist’s radical parents. However, Soleimani’s bold and imaginative narration goes beyond negotiating her family history and offers a conduit for a new way of seeing and feeling.

After experiencing Birds of Passage, I realised the difficulty of isolating these exhibitions. Whilst they are successful as their own entities, the work’s real draw is born from the visitor’s engagement with the work through its constant iteration. She may not admit it, but Soleimani rewards our loyalty. Her provocation to us as viewers is to code-break. Pay attention. Notice every detail and how they build, shift or morph over time. To remain committed to deep listening. ♦

Images courtesy the artist, Edel Assanti, London, and Denny Gallery, New York © Sheida Soleimani

Installation views of Birds of Passage, at Denny Gallery, New York, from 5 September – 7 October 2023.

—

Gem Fletcher is a writer and host of The Messy Truth podcast, a series of candid conversations that unpack the future of visual culture and what it means to be a photographer today. Her writing has been published in Foam, Aperture, British Journal of Photography, Creative Review, It’s Nice That and AnOther.

Images:

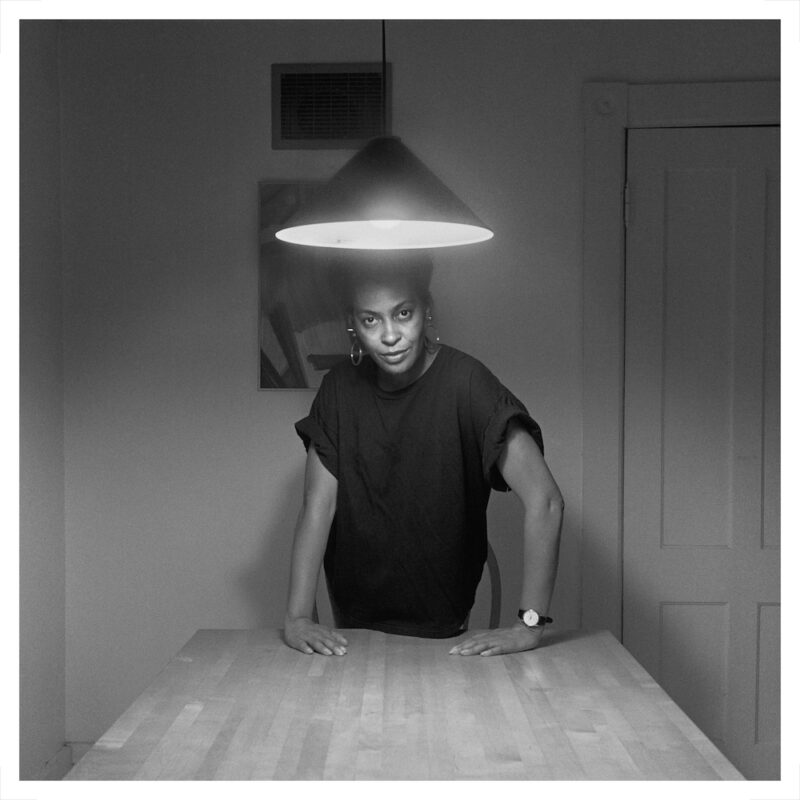

1-What a Revolutionary Must Know, 2022 © Sheida Soleimani

2-Noon-o-namak (bread and salt), 2021 © Sheida Soleimani

3-Crying Quince, Laughing Apple, 2022 © Sheida Soleimani

4-Khoy, 2021 © Sheida Soleimani

5-Agitator, 2023 © Sheida Soleimani

6-Panjereh, 2022 © Sheida Soleimani

7-Remorse, 2023 © Sheida Soleimani

8-Behind the Door, 2022 © Sheida Soleimani

9-Safar, 2022 © Sheida Soleimani

10-Field Hospital, 2022 © Sheida Soleimani

11>13-Installation views of Birds of Passage, at Denny Gallery, New York.