Catherine Opie

harmony is fraught

Exhibition review by Zachary Korol Gold

Comprising constellations of never-before-exhibited photographs, Catherine Opie’s latest exhibition with Regen Projects raids the artist’s archive and offers windows into her community, city and social life, burrowing into the surface of Los Angeles like the famous cuts on the artist’s back, writes Zachary Korol Gold. Our must-see show during Frieze Los Angeles 2024.

Zachary Korol Gold | Exhibition review | 26 Feb 2024

Entering Regen Projects here in Los Angeles, the sounds of a group of friends hanging out at the back of the gallery greeted me. Making my way through the gallery’s rooms, divided in four equal quadrants with one long hallway, one voice became distinct: that of Catherine Opie, whose exhibition harmony is fraught, the artist’s eleventh with Regen, surrounded me. Curious to see whether Opie was leading a tour or catching up with the gallery’s proprietor and namesake Shaun, her long-time friend, I made my way to the back of the space.

The artist, however, was not present. Instead, I discovered Making of Self-Portrait/Cutting (1993), a half-hour-long behind-the-scenes video of Opie’s Self-Portrait/Cutting, 1993 (1993). In this seminal colour photograph, not on show, a childlike cartoon of two stick figures, both in triangular dresses, holding hands, adjacent to a house, cloud and cresting sun, has been cut into the artist’s bare back, beginning to ooze blood. Making of presents the moments preparing, cutting and capturing this well-known picture. Whereas the photograph depicts a solitary Opie, appearing serious, heavy and verging on the grotesque, the film depicts a group coming together to realise an artwork, their chatting and joking overlaid with a buzz of energy foreshadowing the gravitas of the still.

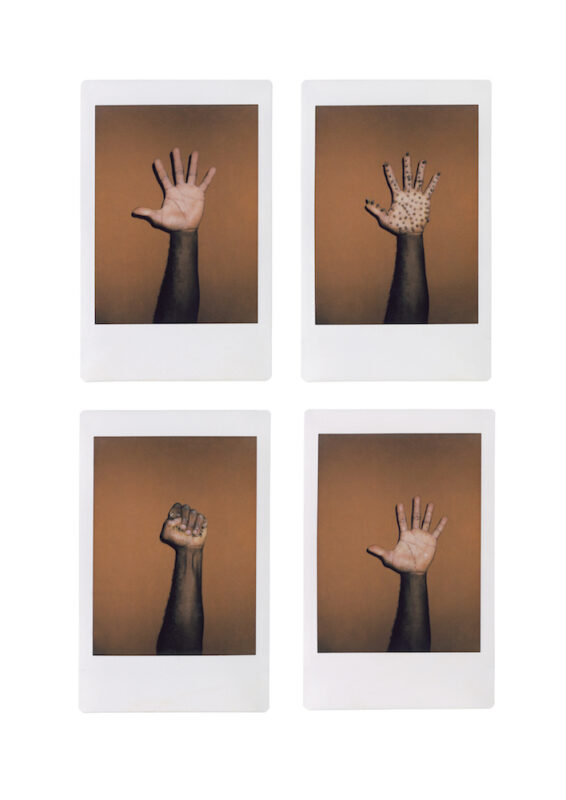

In an adjacent room, another work draws from this same moment: Self-Portrait/Cutting contact sheet, 1993 (1993/2024). Here, four shots of Opie’s back come together in a “contact sheet”, photo-sensitive paper directly exposed to a group of negatives pressed against it – contacting it – used to catalogue pictures for an artist’s archive, and a source from which one can be selected for enlargement into a final print. This image, whose four quadrants mirror the gallery’s four symmetrical spaces, repeats the photographic processes of exposure, printing, scanning; its negatives captured and the contact sheet exposed in 1993, then digitally scanned and finally printed in 2024. Such re-photography recalls the postmodernist experiments of Sherrie Levine, who presented her own photographs of photographs directly appropriating the iconic works of Walker Evans, Eliot Porter and Edward Weston. The so-called “straightness” of Levine’s appropriations is here displaced, both by its picturing of an image carved into Opie’s body rather than one from the photographic canon, and in the present exhibition’s context of Opie’s social life which bleeds in from the sounds of Making of around the corner, as well as the artist’s community and city on display in other pictures.

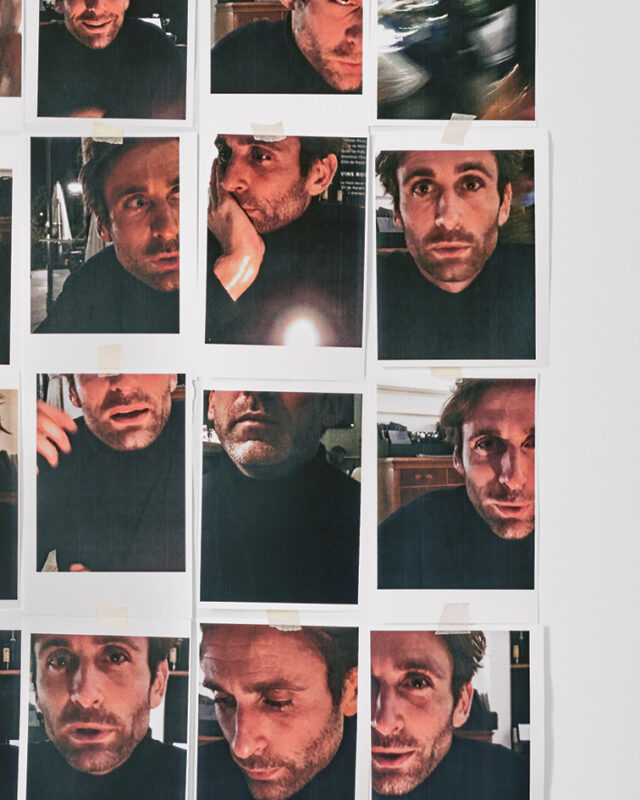

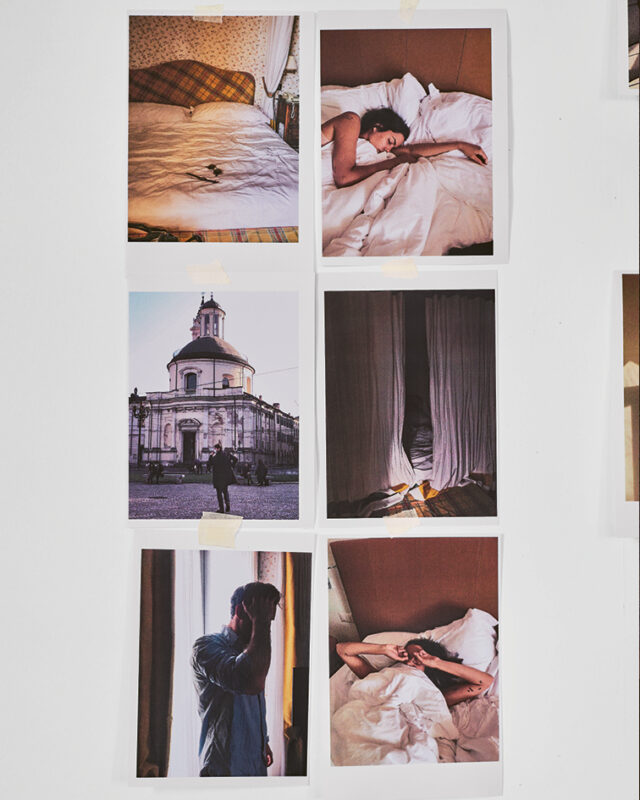

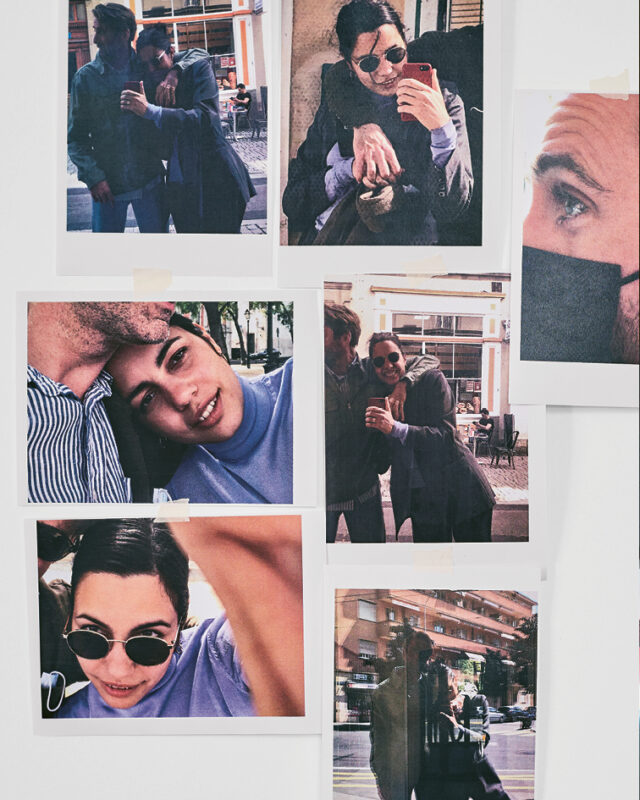

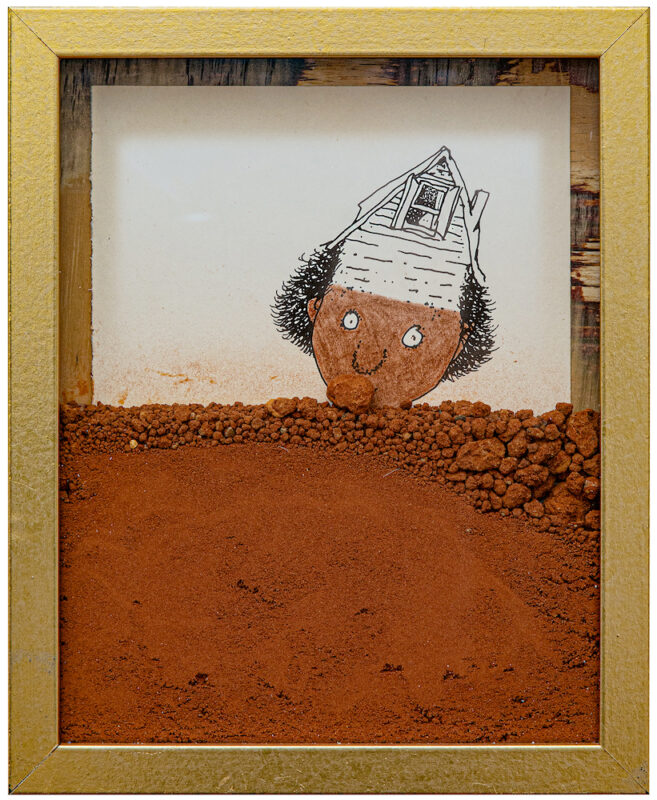

Like Self-Portrait/Cutting contact sheet, the exhibition raids the icebox of Opie’s own archive; the artist invites us to look with her through her personal contact sheets. And many of the pictures are of her contacts. Studio mates, artists, friends, Opie’s son Oliver and others gather among scenes of domestic life, parties and the urban spaces of Los Angeles.

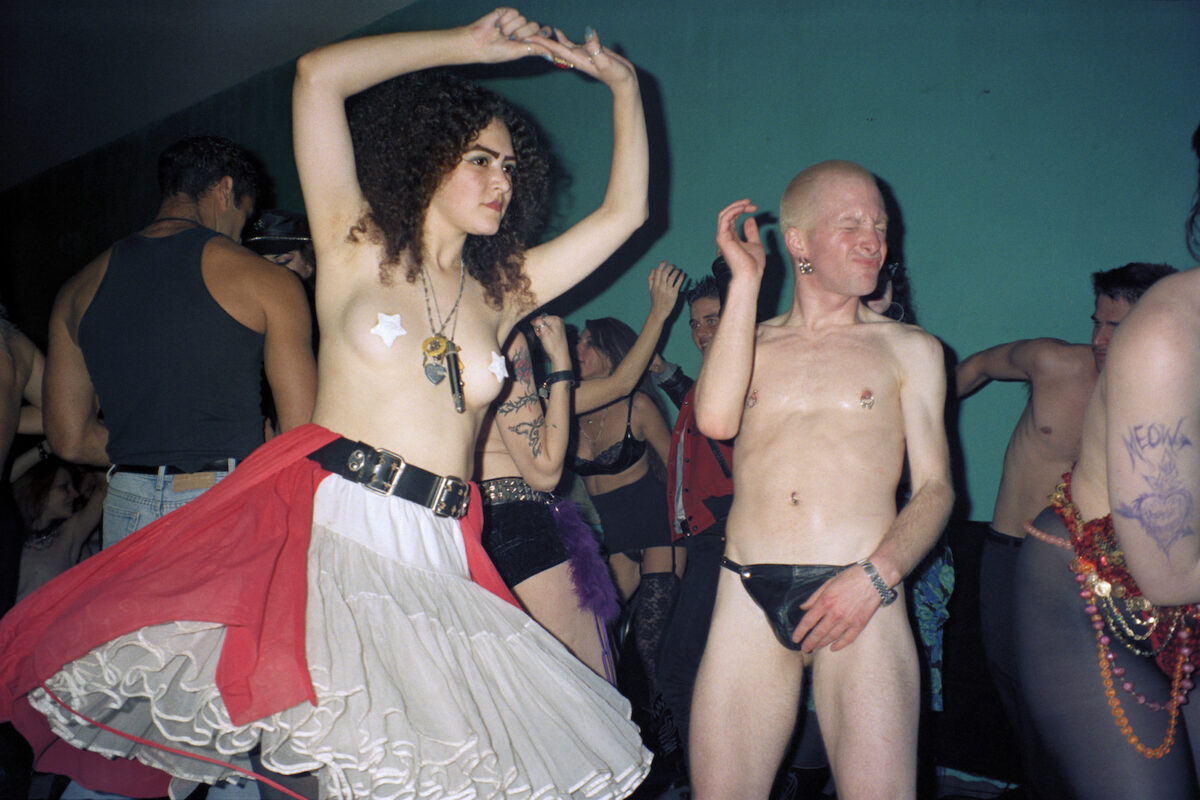

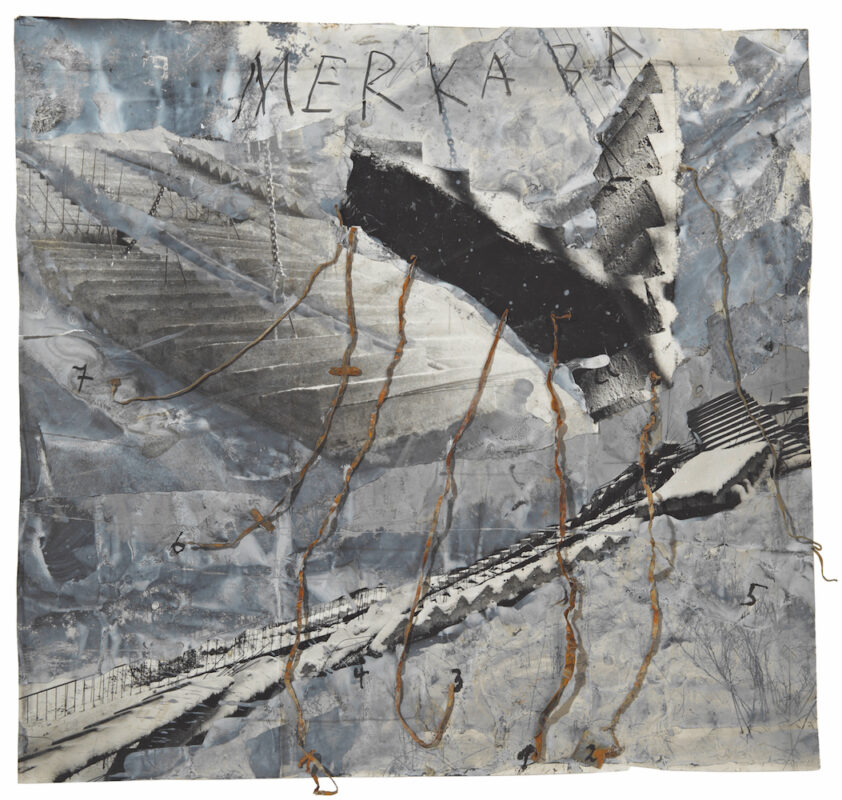

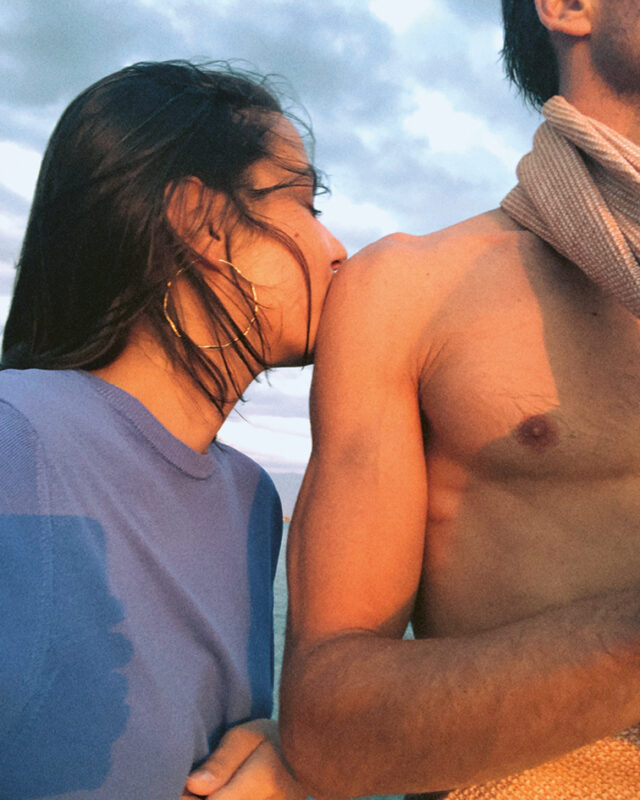

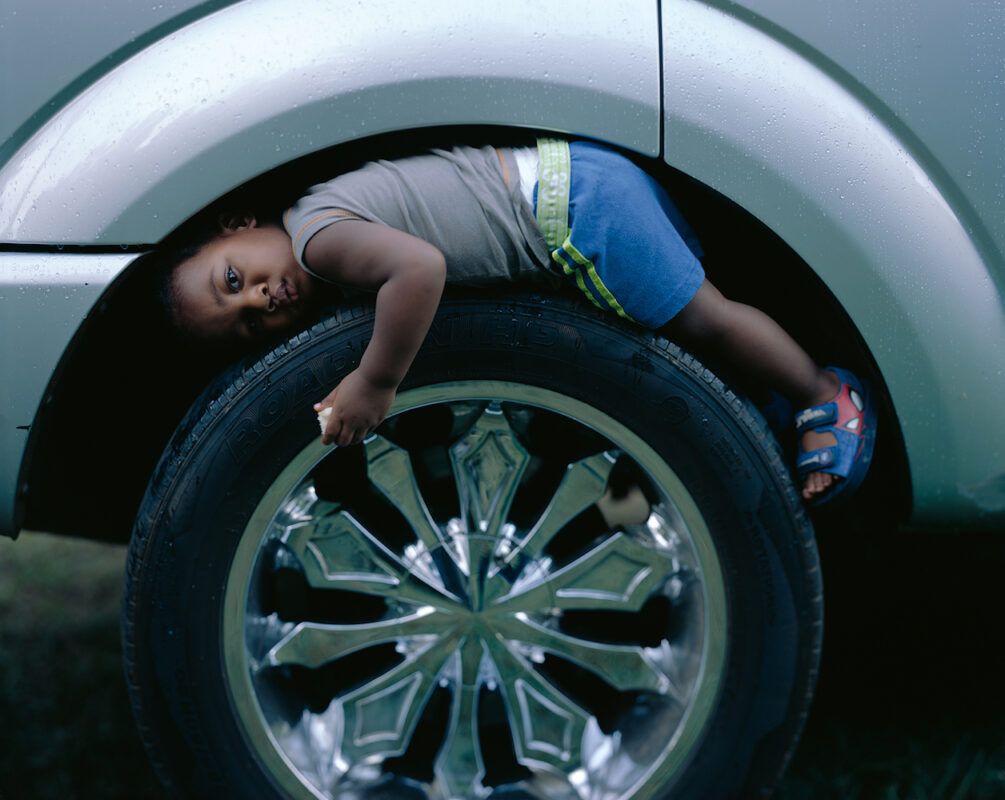

Along the longest corridor-like gallery, Opie plastered a wall with a monumental vinyl of her 1993 night-time picture of the exterior of The Palms, the last remaining lesbian bar in West Hollywood that shuttered in 2013 after nearly half a century in operation. A group of pictures of party-goers in various states of undress cluster atop the nearly life-sized wallpapered image of the bar. Here, Club Fuck #1 (1992/2024) and Club Fuck #2 (1992/2024) both depict scenes of debauchery at the infamous party Club Fuck!, hosting performances and dancing at Basgo’s Disco and Dragonfly Bar between 1989 and 1993 until it was shut down by police. Conflating these parties with The Palms, Opie threads together the overlapping lesbian queer, and arts communities – her communities – of 1990s Los Angeles.

The exhibition at large hinges on this same operation, bringing together portraits of the artist’s people, scenes of her city and windows into her life. The artworks resurrect images from the artist’s archive which had remained private, never shown before, now loosely arranged in an eye-level succession spread across the gallery. This structure invites us to flip back and forth through Opie’s pictures as if we were sitting down with her and cracking open a photo album. Whereas the family photo album upholds the family unit as a source of chronological collective memory – as theorised by Pierre Bourdieu – here, pictures are associated but not ordered. The openness of the selection at Regen Projects does not pretend to aim for comprehension. Opie holds no secrets, and the show’s very exposure of her life centres its incompleteness with no pretence of achieving objectivity.

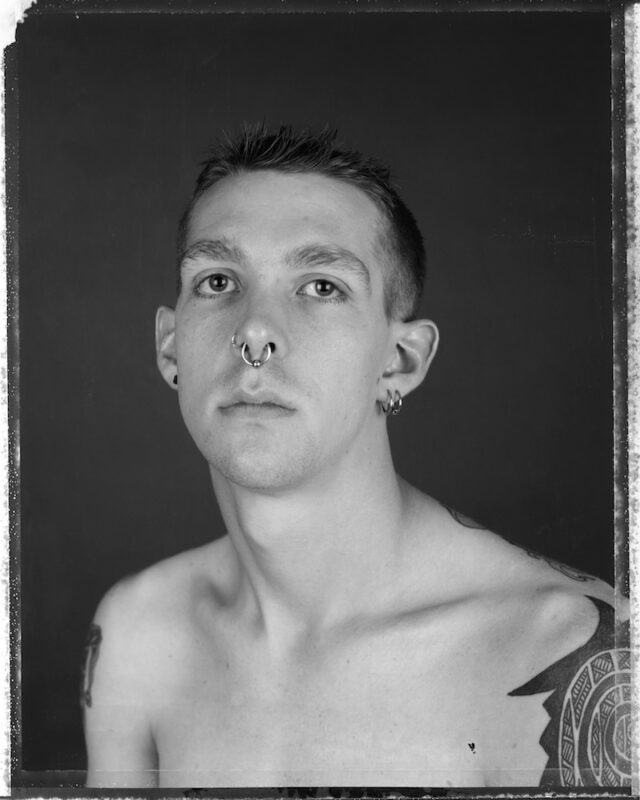

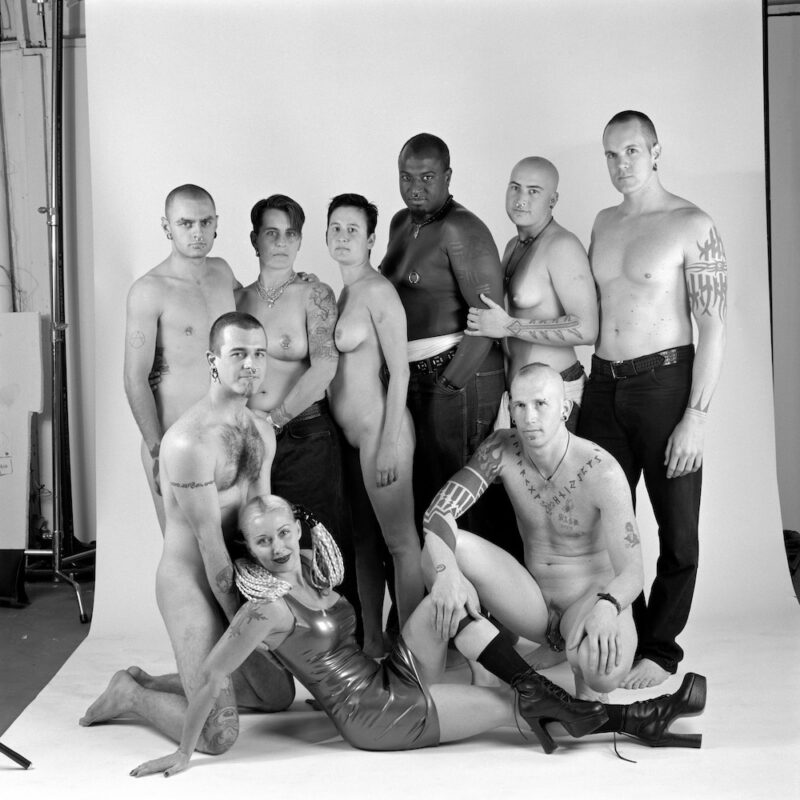

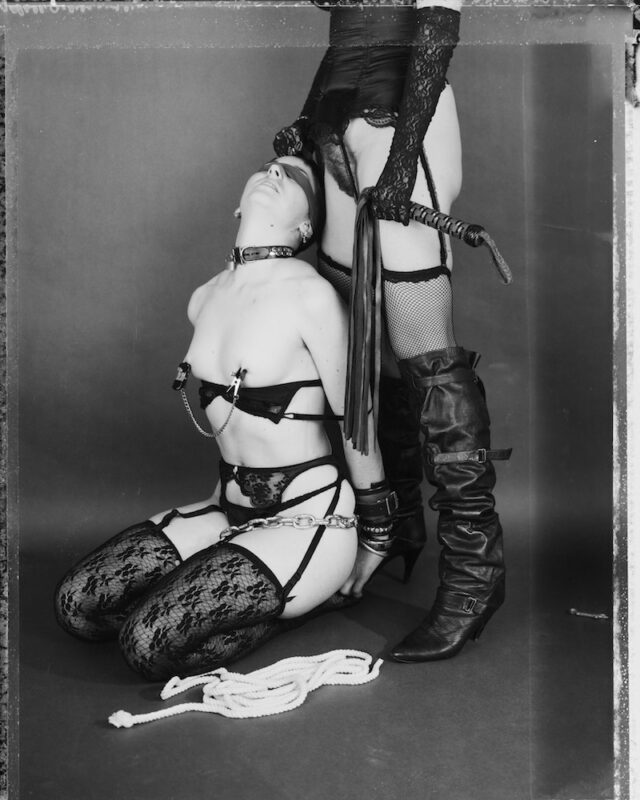

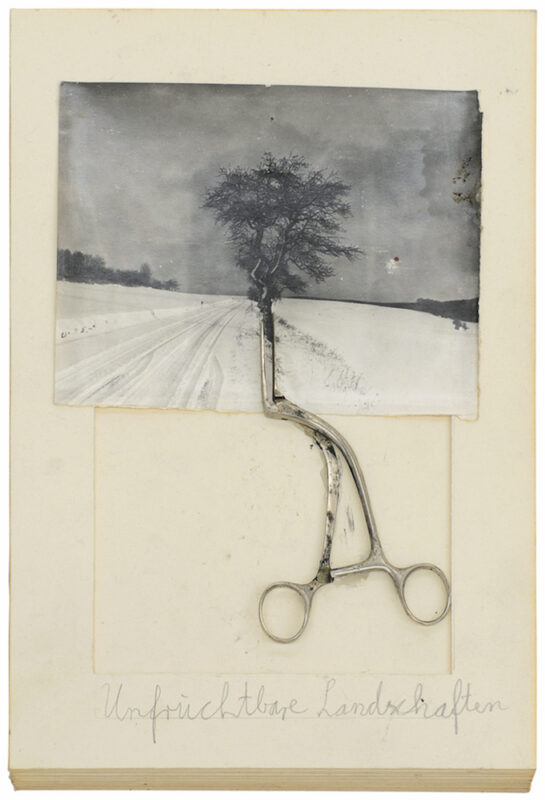

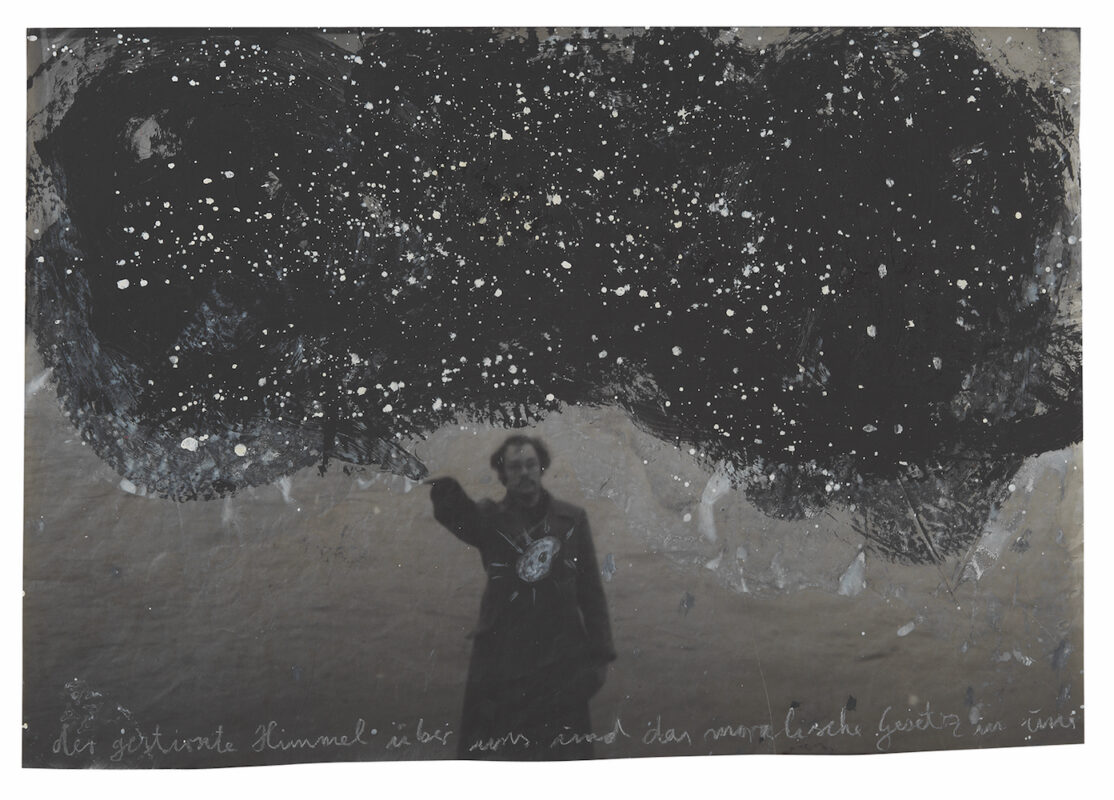

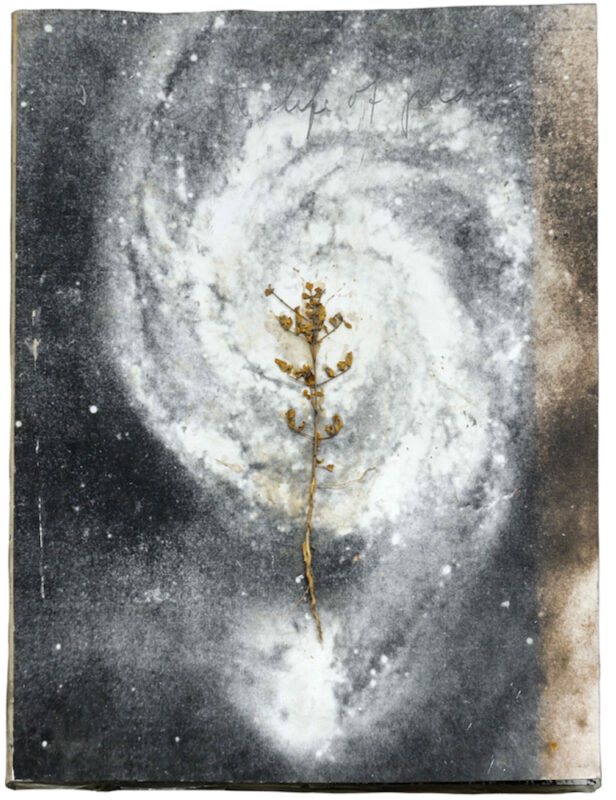

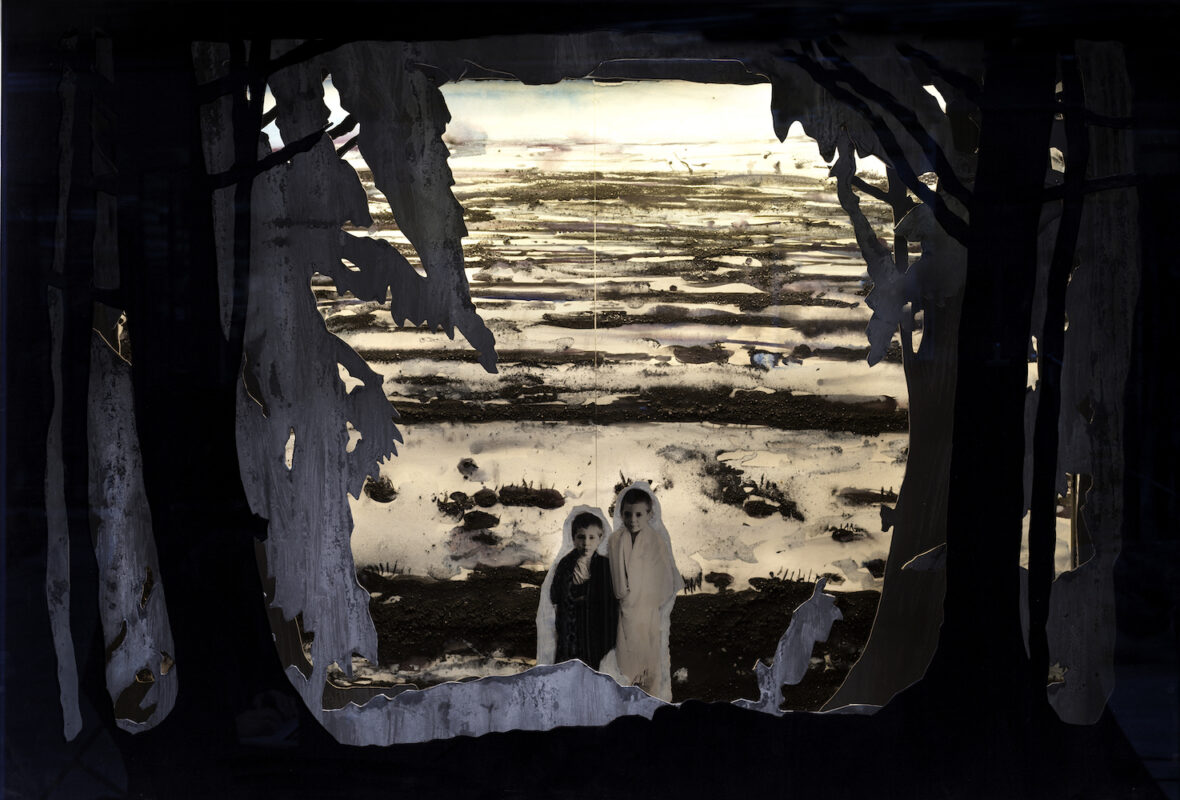

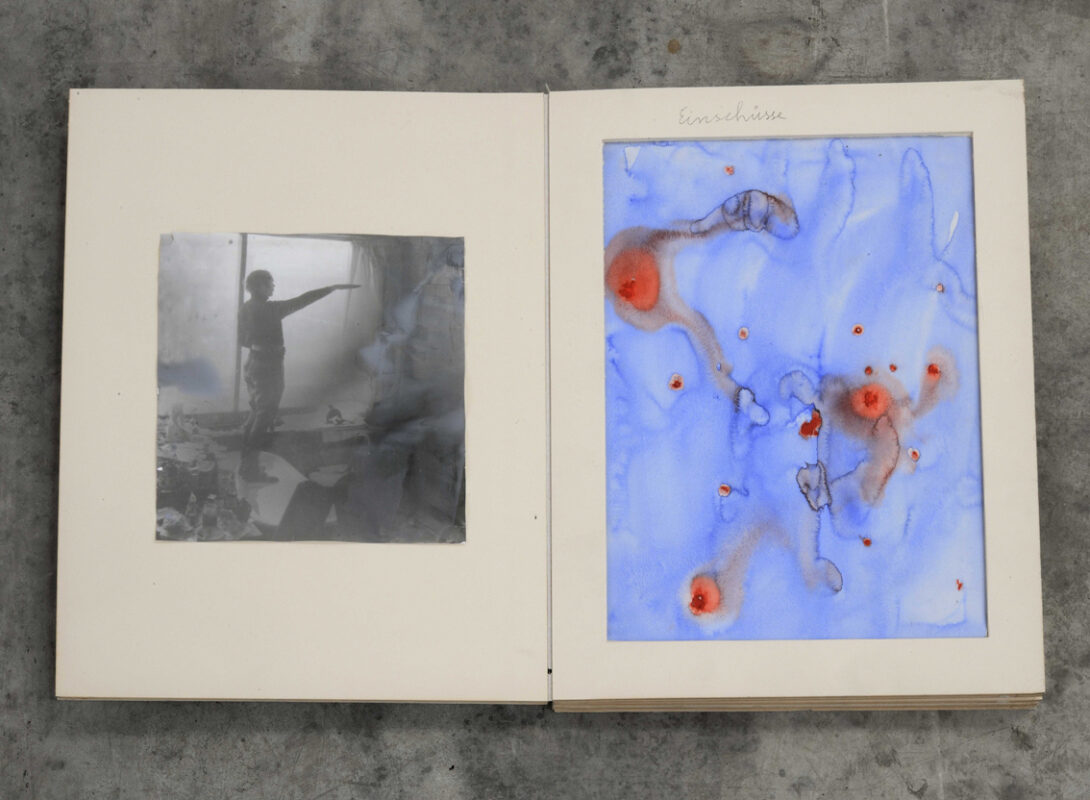

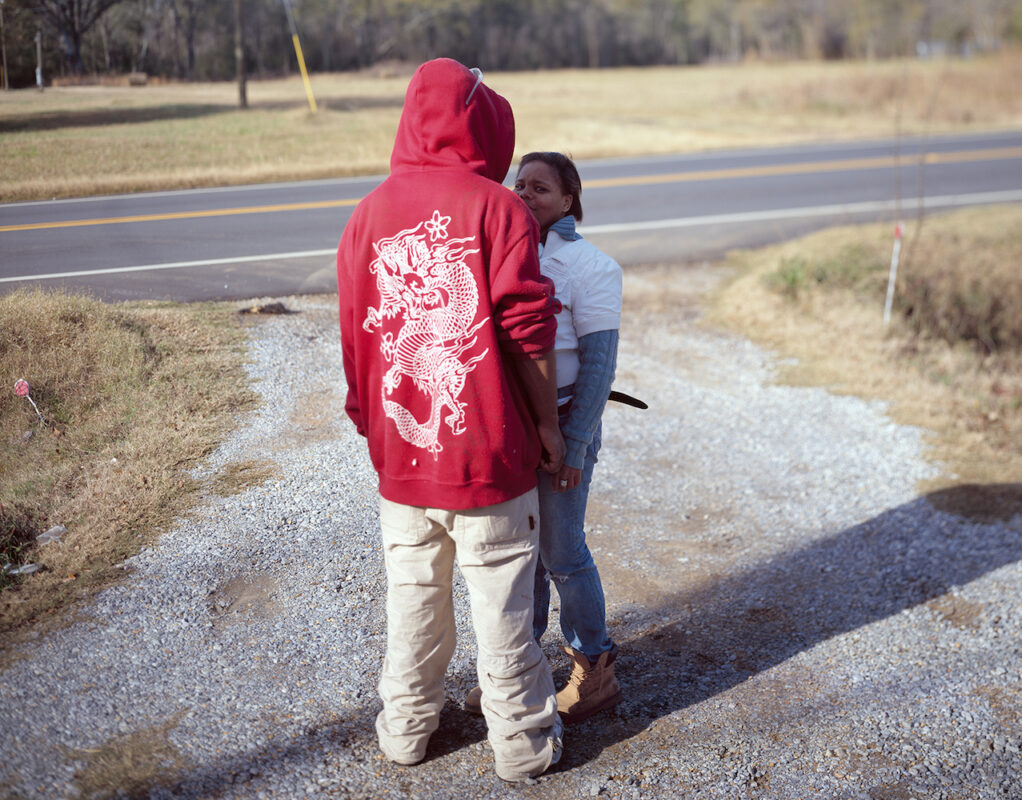

This comes to the fore in the many pictures of domestic and urban life and space, that the portraits punctuate. The city records its inhabitants’ layered interventions, the coverings, paintings, marks and erasures that occur through its ongoing occupation. Graffiti covers the edges and road barriers of an ominously-empty interchange in 105 Freeway, 1994 (1994/2024), a mural decrying gangs adorns a building standing behind an empty lot in End Thee Insanity, 1989 (1989/2024), plywood covers a store’s windows during the 1992 uprising in Mariella’s Tacos/Uprising, 1992 (1992/2024) while a fire burns another building during the same moment of unrest in L.A. Uprising, Catalina Rooftop, 1992 (1992/2024). Surfaces are constructed and built up, both in private in the mood board of printouts tacked to the wall in Tony Greene’s Studio, September 12, 1990 (1990/2024) and connecting the city in the replacement sixth street viaduct to downtown in 6th St. Bridge Construction, 2022 (2022/2024). Violence erupts, both threatening, like the armed police in AB101 Demonstration, 1991 (1991/2024) and camouflaged guards in Mariella’s Tacos/Uprising, 1992 (1992/2024), and pleasurable, in the BDSM practices of needle play in Ian needles and flowers, 1993 (1993/2024) and the kneeling exchange of Yes Ma’am, 1990 (1990/2024). Intimacy, here, can be the peaceful hammocked nap of Catherine and Millie, 1994 (1994/2024), the raucous lust of the Club Fuck! pictures and the vulnerability of the dildo, lubricant and hemorrhoidal suppositories on display in Medicine Cabinet, 1992 (1992/2024).

Like a series of long exposures, public and private surfaces record the history of Opie’s city’s community. As she and we make our lives here, we burrow into its surface like the famous cuts on the artist’s back. We meet each other, we touch the city, making contacts. ♦

All images courtesy the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Catherine Opie

harmony is fraught runs at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, until 3 March 2024.

—

Zachary Korol Gold is a curator and writer living in Los Angeles researching ecological aesthetics in contemporary art. He is a PhD Candidate in Visual Studies at the University of California, Irvine and works in the curatorial department of UCI Langson Institute and Museum of California Art.

Images:

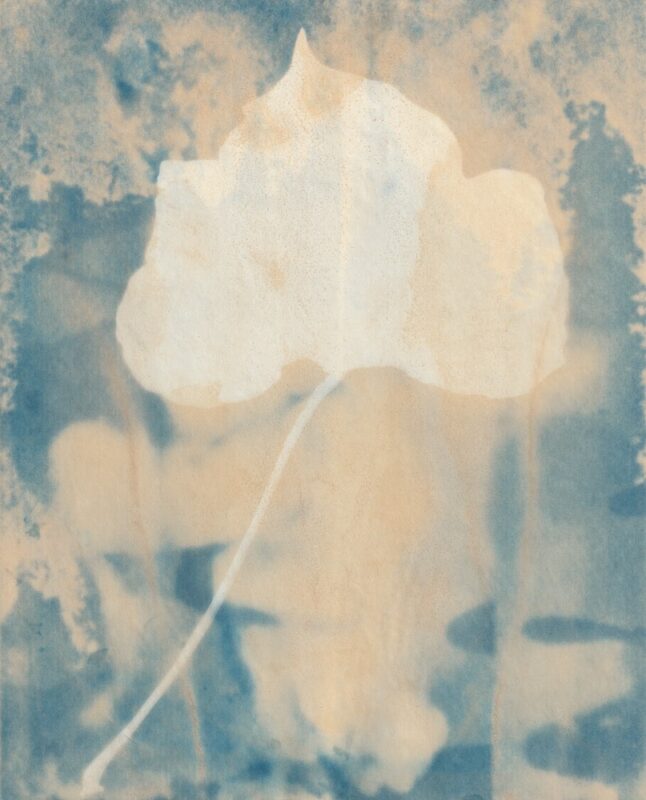

1-Catherine Opie, 6th St. Bridge Construction, 2022 (2022/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

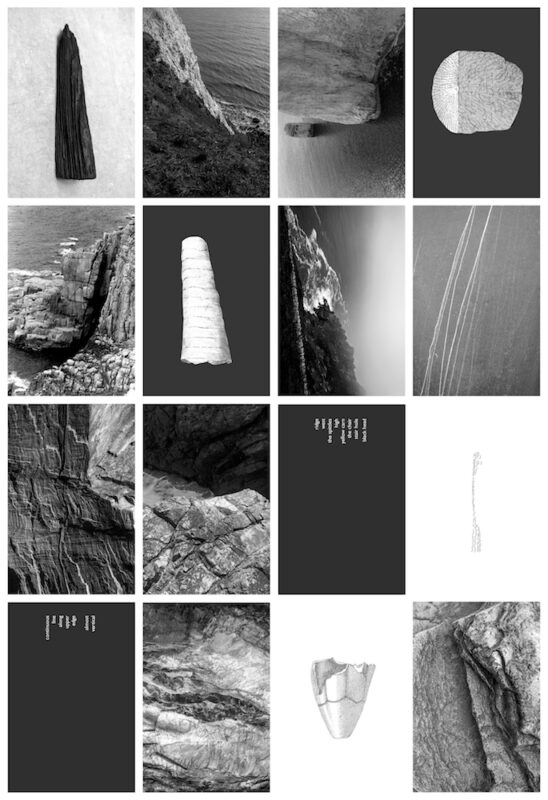

2-Catherine Opie, AB101 Demonstration, 1991 (1991/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

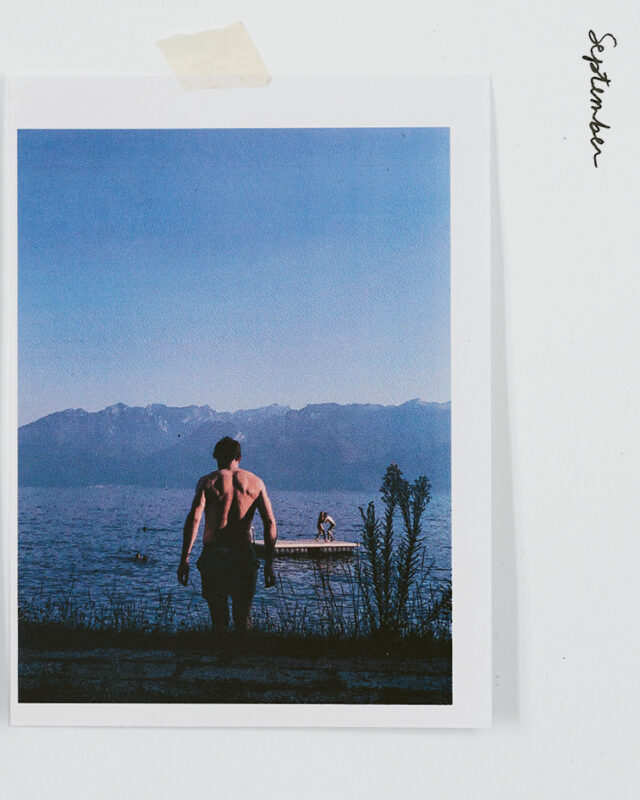

3-Catherine Opie, Catherine and Millie, 1994 (1994/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

4-Catherine Opie, Club Fuck #1, 1992 (1992/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

5-Catherine Opie, Club Fuck #2, 1992 (1992/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

6-Catherine Opie, Christian, 1990 (1990/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

7-Catherine Opie, Gauntlet Group, 1995 (1995/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

8-Catherine Opie, Hollywood, 1990 (1990/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

9-Catherine Opie, Ian needles and flowers, 1993 (1993/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

10-Catherine Opie, Mariella’s Tacos/Uprising, 1992 (1992/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

11-Catherine Opie, Medicine Cabinet, 1992 (1992/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

12-Catherine Opie, Sunday morning, 1989 (1989/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

13-Catherine Opie, Surfer Landscape, 2003 (2003/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

14-Catherine Opie, Yes Ma’am, 1990 (1990/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

15-Catherine Opie, Langer’s, 1989 (1989/2024). Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.