Edgar Martins

Siloquies and Soliloquies on Death, Life and Other Interludes

Essay by Daniel C. Blight

“You talk about death very flatly”, says one of Roland Barthes’ students disdainfully upon leaving his class. These words are Barthes’ own segue into his concept of ‘flat death’: the flat surface of the photograph and the ironic flatness of death itself, which the writer identifies by having, in Camera Lucida, “nothing to say” about the subject. Death is an ineffable thing. It’s very difficult to write about, and it’s even more complex to find anything new to say when doing so. Perhaps there is literally nothing to say; what do we, the living, know about it really? This ‘literally’ – one often heard and ambiguous colloquialism of our time – is, as we shall see, important in considering the connection between death and soliloquy. Or put simply, death and the language of photography, an idea central to Edgar Martins’ work here.

Siloquies and Soliloquies on Death, Life and Other Interludes is in fact several parallel projects, not least various iterations of the work in exhibition form, but also a substantial book project. As the introductory essay by Sérgio Mah tells us, Edgar Martins shot in excess of a thousand photos, and scanned more than three thousand from the archives in the National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences (INMLCF) in Portugal. Displayed in complex and elegant sequences – visual testaments to the complications of thinking death, and to the idea of an interlude, be it between the world of the living and the dead, or in the space between ordered images.

The writer Laura Mulvey offers us a crucial scheme, in two parts, with which to think photography’s relationship to death. First, she suggests that there is a sense of intellectual uncertainty on the subject of death, which finds expression in Barthes’ stiflement in Camera Lucida (1980), and more recently in Thomas W. Laqueur’s The Work of the Dead (2015), which foregrounds the importance of, as he puts it, the longue durée – similar patterns and cycles of thinking about, and behaving towards, death that appear over and over again in its long cultural history. Second, Mulvey goes on to state that it is impossible to consider, at its fundament, that photography is a language and a system of meaning bound to expression through signs.

If one cultural history of death is the history of intellectual inconstancy, and the other is the difficulty in reducing the photograph to a linguistic system of meaning, where does that leave us, and indeed Edgar Martins’ project? It seems reasonable to assume that any intellectual endeavour on the subject of death in the context of photography should take stock of this. Returning to a discussion of the words ‘literally’ and ‘soliloquy’, we may find a partial answer as to how Martins goes about this.

We can’t literally talk of death because its expression requires figuration. In this sense death expressed through language is a ‘figure of thought’, which is an idea obvious enough to any poststructural linguist. However, it is important here as it speaks to our separation from death: a distance both in understanding its meaning, and inasmuch as we attempt to say something about it using words or images, failing as we go. The writer Roger Luckhurst, in another essay in Martins’ book, cites Jacques Derrida, a theorist key to understanding the complexities of language. In doing so, he reiterates one of the central tenets of Derrida’s theory of deconstruction: that writing – and therefore we might say photography, as it is generally understood to be at least a quasi-language – can never be “finally identified or exhaustively delimited.” The meaning of a photograph is flexible, figurative and best understood as operating within a system of changing tropes – metaphor and irony being the most familiar to us. Analogy, as we find in Kaja Silverman’s book on photography, The Miracle of Analogy (2015), is another literary expression of theoretical importance to understanding photography’s relationship to death. She writes, “a death mask analogises the face that shaped it.” We might similarly suggest that in more general terms, the photograph analogises the world that shapes it.

One history of photography is a history of literature; or at least a history constituted in part by photography theory importing literary terms from the subject areas of linguistics and literary theory. Equivalently, Edgar Martins engages the complexities of the language of photography by offering us a soliloquy – the literary and dramaturgic thing that it is – on death.

The soliloquy form is, simply and etymologically speaking, the act of talking to oneself. However, as with the study of most words, etymology proves near-on useless for reaching any sense of complex understanding. The other word often associated with soliloquy is ‘discourse’, and it’s here that we find an early Western philosophical relationship between soliloquy and death. In Martins’ book’s final essay by Timothy Secret – the most vivid of the three in the publication – he reflects on how, in an Athenian marketplace, Plato came to realise the “enigma of Socrates’ joviality on the day of his death”. This is the emergence of the concept of a ‘good death’. As is well known, Socrates drinks poison and professes that death is not a thing to be frightened of, but rather an experience to be welcomed bravely. Crucially, Socrates also considers how, as Secret writes, “a life dedicated to reason is itself practicing death”. A synonymic link emerges here: soliloquy is a form of discourse, discourse a form of reasoning, and reason a form of death. Death is here tied, in this Socratic reduction, to the nature of soliloquy understood in the transitions or separations between related literary or philosophical terms.

It is this sense of transition that is important, in my mind, to Martins’ work. The word ‘interlude’ in his project’s title offers a clue. The artist asks us to pay attention to the transitory spaces between his images, which, alongside the photographs as a form of soliloquy, which we must ourselves speak, forms a ‘discourse’ in the sense that the word simultaneously means relation, formation and expression. This is a discourse created by, as Timothy Secret suggests, “an investigation that contributes towards the task of learning to die.” Edgar Martins has, in some strange and profound sense, undertaken a research project that presents detailed visual documentation on the subject of death in the form of a series of fictional extrapolations. He starts with archival images, or ones of his own making; ambiguously appropriates and sequences them; and then asks us to consider two things: the figurative nature of the photographic image as it relates to the involutions of language, and the spaces or interludes between photographs inasmuch as they appear to us as a series of linguistic signs.

Laqueur tells us in The Work of the Dead about the process in which the body’s enzymes literally eat away at flesh post-mortem, thus beginning the process of corporeal decay. Figuratively – to enable one of the medium’s many changing tropes – the photographic study of death is a strange sort of autolysis with which images, as they circulate and propagate, eat away at their own meanings. We might therefore call this photography’s essential figure of thought: like death, photographic images have no inherent meaning, yet it is our task, as people learning to die, to attribute whatever meaning we find worthwhile to them.

It seems that soliloquies articulate the personal construction of a world of language: one speaks to oneself aloud or in the form of an inner monologue. I would hazard a guess that more than 50% of my experiences in life are accompanied by an inner monologue. Sometimes, although not always, that includes me talking to myself about death. I can only imagine a situation where, having spent some time looking at and thinking about Martins’ work as I have, that percentage will increase. That isn’t to say I know anything more about the subject than when I started, but that’s ok, because in the world of the living no one really knows anything about death, which is why we need joviality, soliloquy and analogy to distract us until it arrives. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Edgar Martins

—

Daniel C. Blight is a writer based in London. He is co-editor of Loose Associations, a periodical on image culture published by The Photographers’ Gallery; visiting tutor in the department of Critical & Historical Studies, Royal College of Art and lecturer in photography at the University of Brighton.

—

I-Autopsy technique, circa 1950

II-The albufeira (bayou) of Borba (Alentejo, Portugal), where several suicides by drowning have taken place over the years. Figures published in 2005 showed that the Alentejo district of Odemira had the highest suicide rate in the world, with a rate of 61 suicides for every 1000 inhabitants, 2001

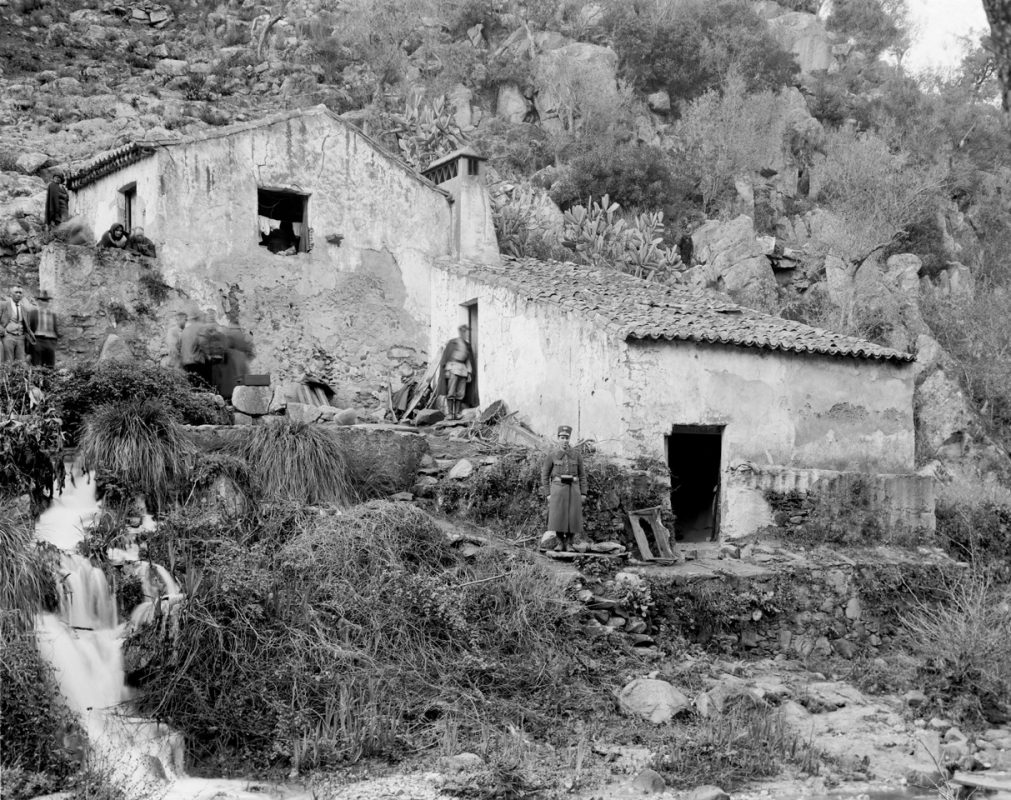

III-‘Bloody drama in a humble home: mother of six is stabbed to death by her husband (1968)’

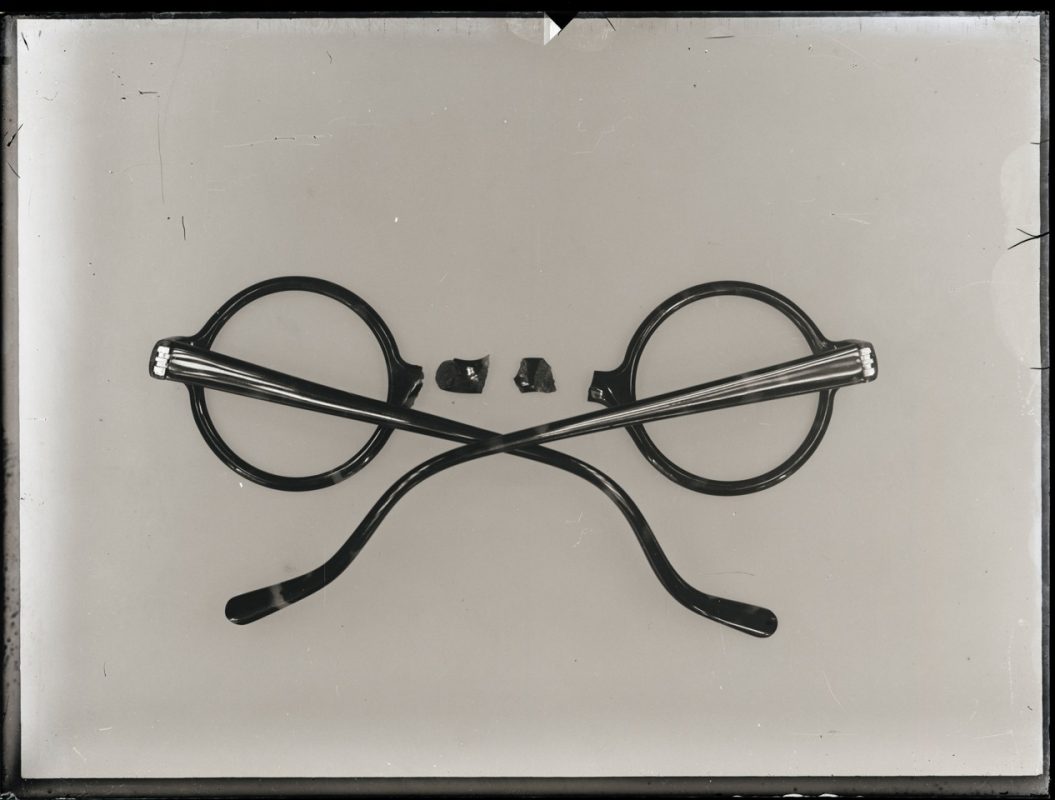

IV-Personal belongings of a deceased individual, 1965

V-Personal belongings of a deceased individual, victim of a crime, circa 1920

VI-‘Man leaves a 1,904-page suicide note and then shoots himself as part of a philosophical exploration (2010)’

VII-Self-inflicted injuries sustained in a suicide attempt by a male involving a knife, 1968

VIII-Suicide by hanging by an inmate at Coimbra Prison in Portugal (2010)

IX-Othalanga nights, 2007

X-When a honeybee stings a person, it leaves a scent mark on its victim that smells like bananas. When one beekeeper had bananas for breakfast and then tried to stock his beehive, the insects poured out and stung him to death, 2016

XI-Albumen print from the collection of Edgar Martins by unknown photographer, circa 1915

XII-Untitled, 2015

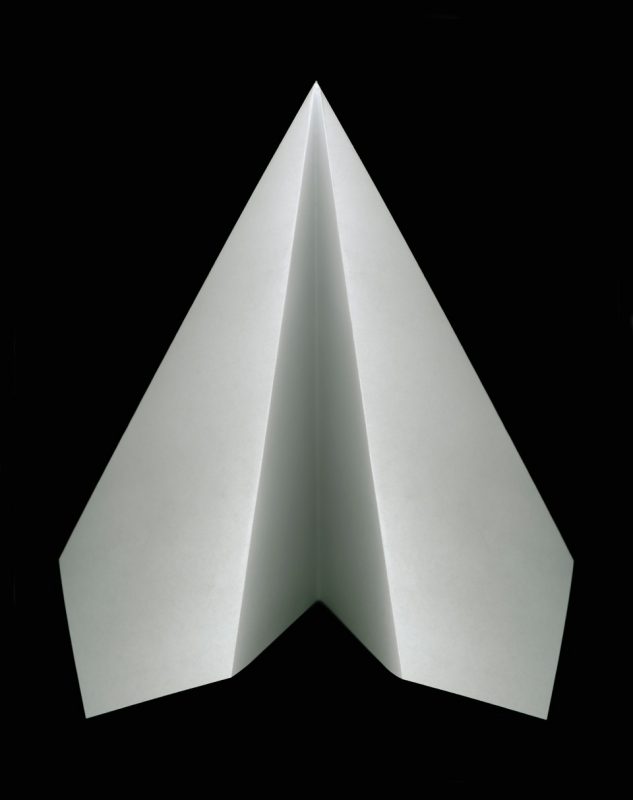

XIII-Paper plane inspired by a suicide letter written by an inmate in the early 1900s, which was thrown from a prison cell window, 2015

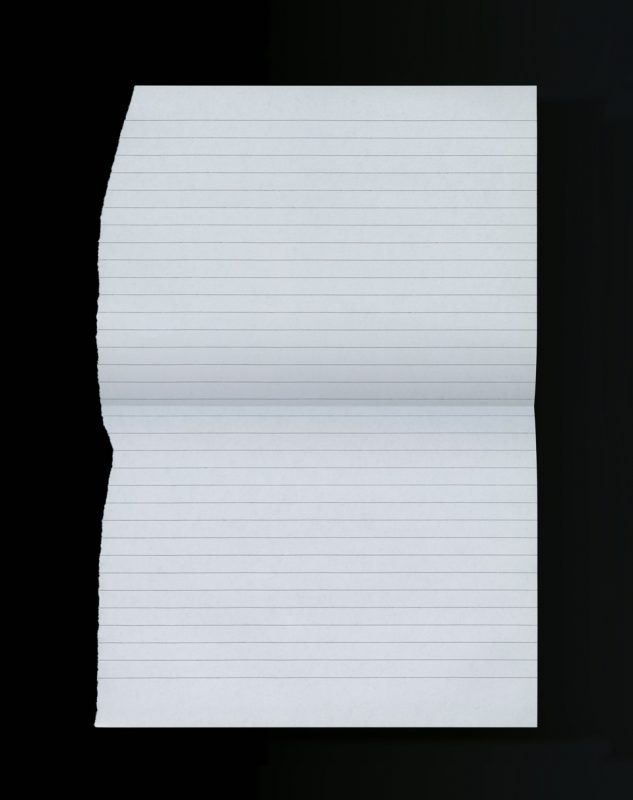

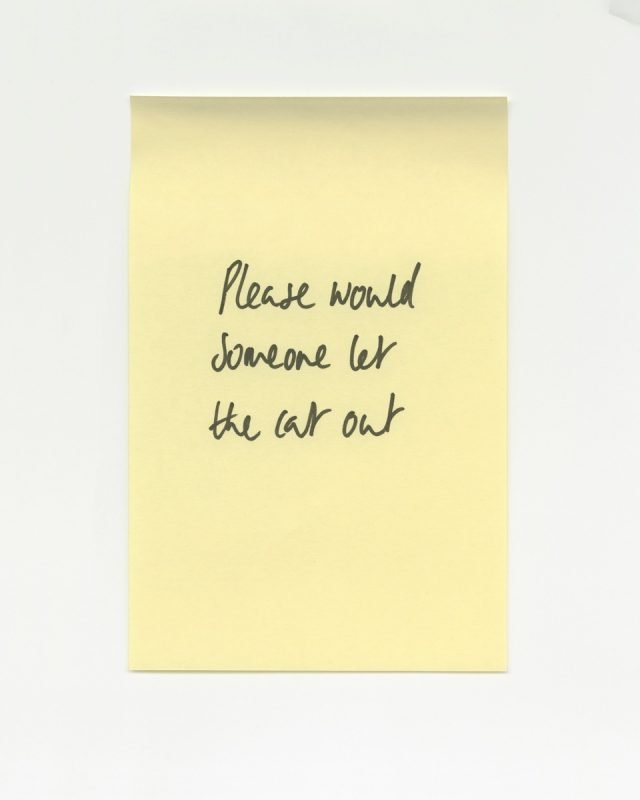

XIV-Note written by a female who died as a result of suicide by poisoning through the ingestion of strychnine (1933), 2015