Forensic Architecture

Saydnaya: Inside a Syrian Torture Prison

Essay by Duncan Wooldridge

With the widely remarked upon image saturation of our culture, it is easily overlooked that the production of visibility, through technologies and networks, produce a parallel world of the invisible and unrepresented. As Ulises Ali Mejias has written in Off The Network: Disrupting The Digital World, the nodes on a digital network are trained to recognise only other nodes. In the network, an object that does not appear to be a node simply does not exist. Such is the network’s blindspot, recognising only itself. And so it is for our positivist relationship with visibility, with a world that is continuously imaged. The history of photography is laden with such notions: that the world exists to be photographed; that an object/place has not been truly seen until there is a photograph of it. We are largely unconscious that our regime of visibility, dependent upon the photograph as it is, also produces a world of invisibility, with objects, places and peoples that seemingly do not exist.

It is necessarily the case that if a culture is built around an apparatus like photography and the exchange of photographic images, a parallel culture will emerge where photography is resisted (perhaps to return to privacy) or prohibited (in order to construct alternative regimes of power). Such a world might be a respite from the unrelenting flow of media, information and chatter, but it might also conceal a deeply choreographed programme of violence. How would we bring such a world into view?

The research organisation Forensic Architecture explores the gaps between images. It produces analytical evidence to participate in the production of both political and juridical facts, relating to areas of conflict and sites of humanitarian crises. Using archaeological and forensic tools first developed to generate evidence and demonstrate the course of decades-old war crimes (see Thomas Keenan and Eyal Weizman’s Mengele’s Skull), Forensic Architecture has merged forensic procedures with new combinations of images sources and data analysis tools, to reveal how buildings both produce and bear the scars of control, and how these affect human subjects. Weizman describes this process as expanding the juridical process so that objects themselves can be sources of information and effectively placed within the context of a trial. One project, entitled A Drone Strike in Miranshah: Investigating Video Testimony, exhibited in the 2015-16 exhibition Burden of Proof: The Construction of Visual Evidence assembles uploaded civilian photographic and video recordings to produce real-time 3D-mapped and geo-tagged verifications of drone attacks in Palestine.

Forensic Architecture projects counter government accusations of digital manipulation – an open but hard-to-refute claim made by numerous government forces – and strategies of hiding or concealing, by using multiple images as an accumulation of information which can be abstractly mapped. In using a combination of archaeological, forensic and photographic tools, Forensic Architectures demonstrates new expanded strategies of documentary practice, interlinking the documentary mode of ‘witnessing’ with analytical research, whilst providing real, juridical evidence.

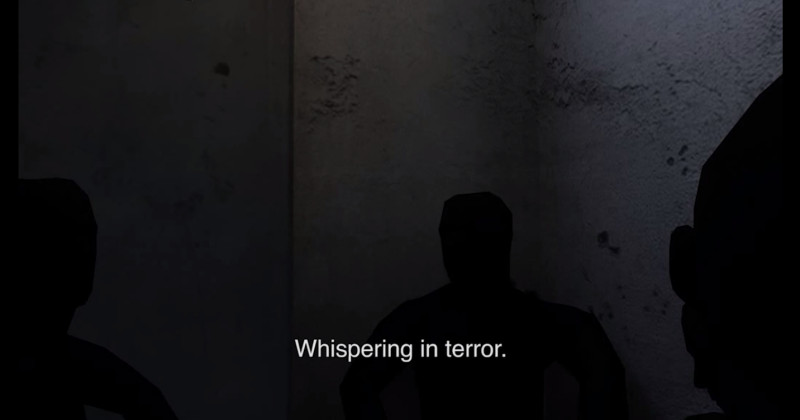

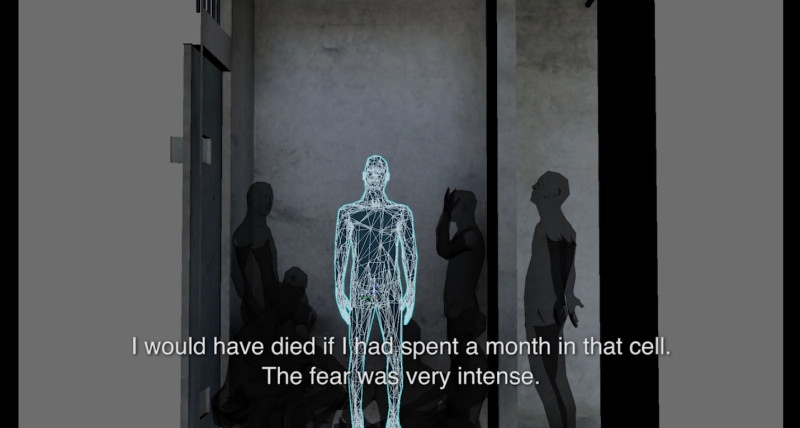

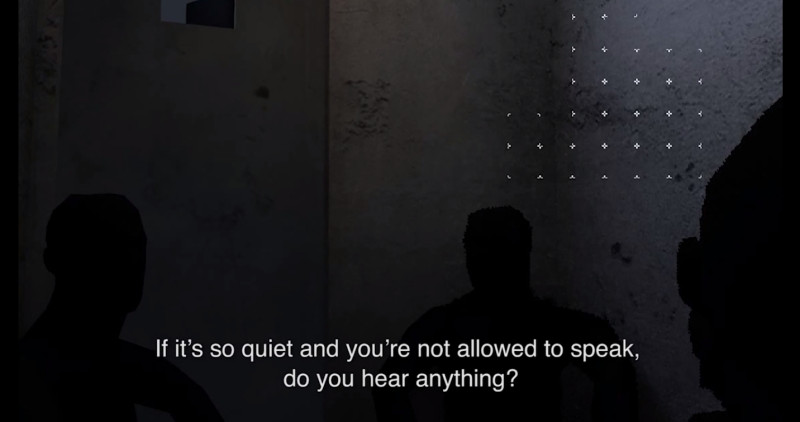

Saydnaya: Inside a Syrian Torture Prison begins, however, at the very limit of photographic evidence. Saydnaya Prison is located 25km north of Damascus in Syria, and has been the site of civilian tortures since 2011. The prison remains out of view however: A single satellite image reveals nothing of what happens inside, and no images are known to exist of the site (in part because no independent visitors have been permitted to visit). The operators of Saydnaya have restricted all acts of photography to conceal any disclosure of the treatment of inmates, a strategy that is further facilitated by the conditions in which prisoners are held and moved around the site in continual darkness.

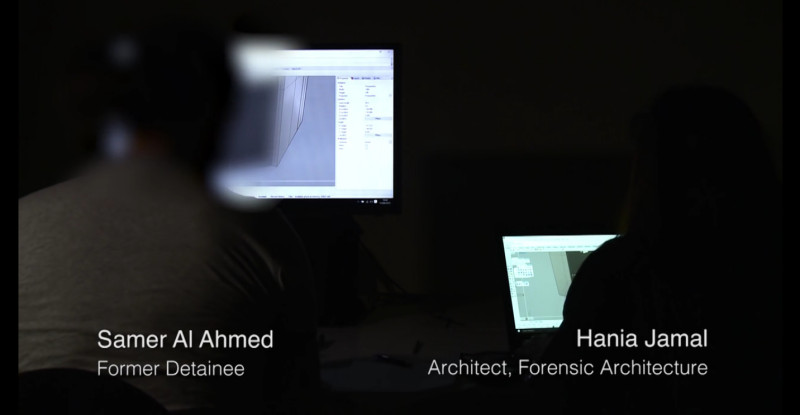

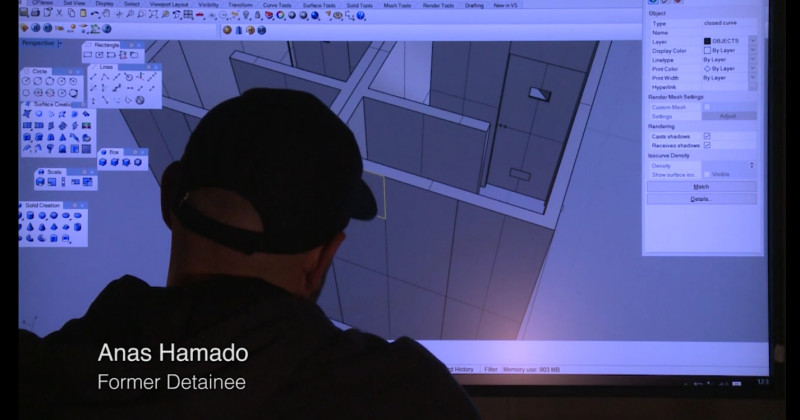

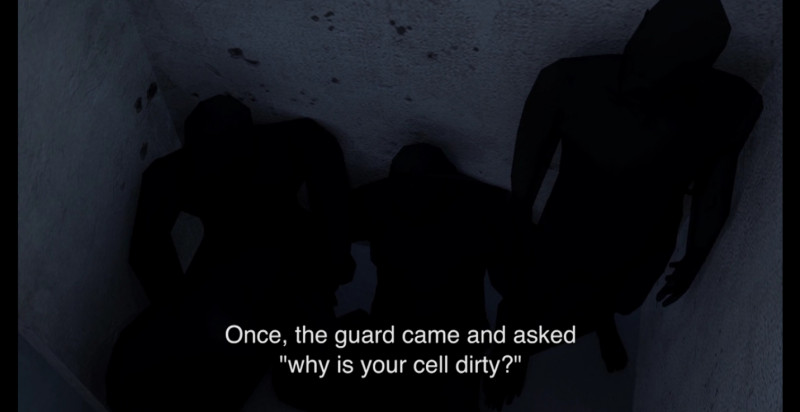

Without even a partial photographic record, Inside a Syrian Torture Prison nevertheless constructs a new body of imagery to make Saydnaya visible. The project responds to the difficulties of obtaining photographic documents by re-establishing the value of human experience as a source of evidence and information, advanced by a forensic focus upon detail. As a reconstruction based around the oral accounts of ex-prisoners – seen through an interactive model of the prison interspersed with interview extracts and video footage of the model’s assembly – it becomes clear the body and mind witness beyond the purely narrative account of the subject. The body and mind trace the site, are imprinted with it. Extensive interviews, where the prison structure and operations are discussed, compared and mapped with architects, form a picture of the building. But with darkened conditions as standard, information is not taken from general or emotive impressions, but from the specific relationships of the body to those architectures, in relation to the size and textures of cells, and the architectural particularities of the site. In one interview, a man recalls a hatch, which corresponds to the size of his skull (through which the inmate was forced to insert his head, sideways, so as to be beaten). The space, in turn, can be measured in reverse, its position towards the floor located by the bodily memory of the witness. Each body maintains the physical residue of the architecture, but the senses similarly maintain a sense of space: the material properties of spaces were reconstructed through acoustic modelling.

Forensic Architecture’s account of Saydnaya begins with an outline shell, but populates the prison with intense details emerging from the human subject. Sense experience is transformed into visible mappings of the site. And temporarily without photographic input, the forensic reconstruction of site and experience re-situate the human agent as a reliable, in fact, valuable witness. Photography could learn from such methods, progressing beyond a notion of fact, or indexicality, to one of testimony for its claim to relevance in the world. If we find ourselves blinded by our dependence upon the image, we find in the human who testifies a key. ♦

All images courtesy of Forensic Architecture. ©Forensic Architecture and Amnesty International

—

Duncan Wooldridge is an artist, writer and curator. He is also Course Director of the BA(Hons) Photography at Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London.