Francis Hodgson

Professor in the Culture of Photography

University of Brighton

In the next instalment of our Interview series, Gemma Padley speaks to Francis Hodgson – critic, professor, photography consultant, co-founder of the Prix Pictet, former head of the photographs department at Sotheby’s, and an advisor specialising in fine photographs for private and public collections – about his thoughts on the contemporary photographic landscape, taking in topics such as whether or not there is such a criteria for ‘good’ photographs, the current boom in photobook self-publishing, and how photography has touched every aspect of our lives.

Gemma Padley: You’ve spoken before about applying a ‘criteria’ for quality when talking about photography. Could you expand upon some of these ideas; how do we decide what is ‘good’ in photography?

Francis Hodgson: I’ve talked about this a lot in the past, both in writing and elsewhere, and I’ve found myself talking about this very strange verb – ‘to matter’. Matter is a very odd word with regard to photography. Because of photography’s fantastic vernacular strength, there’s a tendency to say, “everybody’s equal, everybody’s as good as everybody else”. And then to counteract this by saying, “that person is with such and such gallery”, or, “that person has published a book with so and so”, so that the standards of quality move away from the standards of communication.

I’m certainly a million miles away from saying that the standards of quality are basic technological things about f-stops and accuracy of reproduction; lots of out of focus pictures are completely fantastic, I have no hesitation there. But I do think there has been a tendency over a number of years to confuse the ‘subject’ that’s under consideration with the ‘quality’ of the photographs that consider the subject. There are lots of very bad photographs of serious subjects, and there are lots of very wonderful photographs of complete trivial nonsense.

I’ve been anxiously trying to see whether one can set standards by which one can say, “look, that actually is a bad photograph.” And my gradual tendency is to find myself looking at the notion of communication. Photographs that do not say what the photographer purports they say are not really doing the job that he or she thought they were doing, whereas photographs that say something, that is not much wanted at the time, or is digested 100 years later, really do have that content, [and] seem to me to be closer to what you might call ‘good’ photographs. I realise these are very difficult things to talk about and I’m often accused of being deeply conventional when I look for some kind of standard. Part of it, I have to say, is to do with the intentions of the photographer. A photographer who is trying to say something of course can be understood differently when one uncovers those works fifty or so years later in an archive. Nevertheless, those pictures have a built-in content heaviness if they were successful at getting across what they wanted.

GP: What, to your mind, has been impact of digital technologies on photography, in terms of the creation and dissemination of the medium?

FH: One of the things I see in the great overdosing of photography that goes on in the digital era, where, if you like, pictures are no longer single events or single cultural moments (lots of people talk about a flow of images where you don’t really print, you just get struck by them; for example, you very rarely look at things on Facebook again), is the role of turning oneself into a voluntary archivist if you like – editing pictures and finding some importance in them that was not there when they were first made. I see a lot of people trying to slow down that flow, even at quite modest amateur levels. I see a lot of people curating collections of pictures on their blogs from the vast flow of imagery and they are making those images matter – there’s that word – in ways that the originators of those pictures probably never expected. And that’s absolutely fine by me. It is a way of applying critical standards to something that is otherwise completely neutral.

I’ve been writing a lot about the notion of a new vocabulary [for photography]; I want to talk about people who are ‘photo operators’ to whom the culture of photography is not of any concern. The example I often give is of a traffic warden whose job it is to make ‘x’ amount of photographs per day which quite literally have to be good enough to stand up in court. That person does not describe him or herself as a photographer and yet he or she is using photography to a professionally high standard every time. Another example would be of estate agents who again do not think of themselves as making any allusion to photography and yet everyday they go to visit people’s apartments and make photographs according to a set of standards, and these pictures have to be good by some kind of odd estate agent standard if they’re going to work. But that business of not being involved in the ‘culture’ of photography has spread.

GP: But what has photography’s impact been more widely on other areas of culture?

FH: I refer you to a book, which I regard to be of great importance – Photography Changes Everything by Marvin Heiferman, a project initiated by the Smithsonian Museum. It is really one of the only museums that is, ‘a museum of everything’. It goes, as Marvin says, from A to Z. This meant that in every department of the Smithsonian Museum, not only did they use photography but photography profoundly changed the disciplines in each place. Now that is not a digital phenomenon. If you like I’ll give you a very simple example, which comes from Marvin but which I’ve also written about in the past before I’d read Marvin’s book. If you think about the way that photography bursts into particular fields, in medicine, for example, in the field of ophthalmology; what happened was, photography started as a tool of description and very quickly became the central tool of diagnostics. So now it’s impossible to be an ophthalmologist without using photographs. That’s to say that photographs have actually changed the practice, as they have in anthropology, and so on. Now that has nothing whatsoever to do with digital.

The example that I suppose comes very early on is the business of colonisation. You start in Victorian photographs to look at the notion of other people; people from other countries. Colonisation doesn’t make any sense if a few hardy explorers come back and tell everyone about these things, but the minute photography becomes a standard tool, then colonisation has elements of ethnography built into it. The minute you have those images, colonisation becomes the business of seeking to understand people as well as categorise them. And I’d say this was around 1860, so it’s very early in photography’s history.

The way I describe it – and I always describe it like this – photography is like the Big Bang. It boomed enormously quickly. Photography’s birth date is always given as 1839, but by the mid-1850s there had been an incredibly rapid boom, an explosion. And photography continues to explode into every field that it touches, so that when it touches medicine, it revolutionises that field; when it touches politics, pop music, and so on.

The reason I use the metaphor of the Big Bang is that no one is quite sure what’s left in the middle. The core of the photographic explosion is now in doubt. We’re not sure what photography is. And lots of clever people including philosophers, photographers and lawmakers, when you get to copyright, are asking, ‘what’s left in the middle?’ It’s either an interesting post-modern phenomenon where photography isn’t what we thought it was, or it’s something very different to that – something where we might gradually see that photography isn’t actually a thing in its own right; its done its work, its taught us how to think.

On the most obvious, basic level, at the beginning of the twentieth century, people suddenly realised that photography had profoundly changed the notion of aesthetics. Where we’d previously looked for grace, harmony, balance and some kind of cultural virtue, clearly, once photography does its thing – with things being very interesting when they’re not properly framed, or when perspective is squished – ugliness, squalor, and pain slide onto light sensitive surfaces just as easily as grace and harmony. So photography blew away 500 years of aesthetics. Everybody knows that, that’s not [coming from] me – you can find all sorts of quotes for that. But I think photography did the same thing to lots of very other important fields. And I think that’s the place where we are now.

GP: If this middle no longer exists, then what replaces it? Do we have to create that middle, or try to find something that could take its place? What should the next step be? Do you think we’re scared to face these changes? Perhaps there is a sense that it’s safer to cling on to what’s gone before and what we believe we think photography is? Are we thinking outside of traditional realms of photography or do we need to force the issue?

FH: There are people thinking about these things in very interesting and successful ways, but there is also what you describe – fear. But I find the parallel is exactly like the early days of photography where people were absolutely convinced that photography was going to change industry. There was a huge debate at the Great Exhibition of 1850 as to whether photography should be a product or a process. There’s lots of good writing about this. And I find this exactly parallel to what’s going on now. Take the carte de visite. The idea was hugely popular and not at all dissimilar to how people are working with Instagram now. The carte de visite was considered vulgar and popular and allowed a new kind of social class to play with these things. And it was cheap; it completely altered the mechanics of social interaction among the people who had access to it. So I don’t see how there is any great newness in the philosophical positions, I just think the phenomena at stake need to be thought of afresh.

People are rushing headlong to use the new possibilities of photography, and doing very interesting things with them – that’s great. There’s no problem there. And if you can hang onto some of the cultural wealth that the analysis of photography has produced already, then you can make better sense of these other ways of doing things. I’m excited by the astonishing things one can do with post-photographic tools. The Prix Pictet, in which I’ve been involved since the beginning, remains an astonishing way of getting powerful ideas out to vast numbers of people, which actually change lives. It’s not an art project; it’s a political discourse about globalisation. And that’s done through photographs – like great documentary filmmakers who affect political change even though their stuff is distributed through Hollywood. That’s great – there is nothing wrong with that at all. I’ve no doubt that the root efficiency of photography is not under threat, it is just there are lots of new players and new ways of playing coming in and jostling for attention. I suppose my job is to try and make sense of some of those as they come.

GP: What is your take on photobooks and their function as you see it within contemporary photography?

FH: I’m relatively sceptical about the present explosion of the photobook. The reasons for that are multiple. One of them is the rise of self-publishing; it’s been done under an illusion. When a customer buys a photobook that has come out of this self-publishing or nearly self-publishing market, they still think they’re buying something that has been validated and paid for by a person or a cooperation that has committed to those pictures and that way of telling a story. And that is no longer true. Even utterly respectable publishers are now asking the photographers to pay for the print run or the galleries are paying for it. There’s an illusion of independence, which I think hasn’t been advertised enough. Which is not at all to say that I find all photobooks bad – far from it. But the photobook boom flies under an illusion of neutrality or objectivity when a lot of it is marketing.

The circulation figures of photobooks are simply not in tune with what photography is. It’s very rare to have a photobook that sells a thousand copies. It is closer to the vanity publishing of a few bad sonnets by Victorian poets. I’ve got nothing at all against photobooks. Like everyone else I get a huge hit from the good ones; but, this is not the mass communication medium that we knew all those years ago. This is a medium which is addressing itself to a small and self-selecting group of photobook collectors, many of whom buy two copies of books – they keep one in cellophane, just in case it will be worth more money later on.

So out of your thousand copies of a book, perhaps only 300 are sold to be viewed. This is actually a tiny, self-sustaining sector of a market. As long as one doesn’t have any illusions about that, it’s a jolly interesting phenomenon with lots being produced that’s very exciting. But my view is that people aren’t very clear about that. So you have lots of new interest in the photobook – at fairs and auctions – and lots of photobook activity left, right and centre… but actually, that does not equate to a great boom in the influencing of people through images, which is what photography at its root, was.

For example, if you go to see a show like Donovan Wylie’s great exhibition Vision as Power at the Imperial War Museum, which explore modern-day surveillance, what you see is a really fantastic set of objects that are three or four feet across. And when you buy the book of those things you get an index of what you saw, a kind of sequence. But there is no great mass communication hit from that book. The photobook is the catalogue of a really powerful and publically effective exhibition. Huge numbers of people thought about the way modern colonialism works in different ways to the ways they’d thought about it before, but not through the book. The exhibition and the magazine publications that come out around the time of the exhibition are doing a really powerful communication job. But the book is not, even though it is a jolly good book. And that to me seems likes a really frequent phenomenon. The project comes out, it’s done in a show, the show is publicised in magazines, and the magazines get 20 to 40,000 people seeing the thing, not for very long. Those [articles] are reproduced online, that gets 100,000 people seeing the thing – online – if it’s exciting, and at the end, there is a high value, small, circulation object – the book, which is collectable but no longer has very much heft in the communication moment that’s at stake. And that seems to me to not yet have been articulately shared with people. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying that photobooks are crap, I’m saying that the job they do is not the job that they purport to do.

GP: You’ve worked and continue to work in many different areas within photography – from education, as professor of the culture of photography at the University of Brighton, to the art world, through the consultancy work that you do and your time at Sotheby’s as head of the photography department, commercially, and of course in your writing for the Financial Times and other publications and institutions. How, for you, do these different disciplines relate to each other, and how do you manage to keep all the plates in the air, so to speak?

FH: I think of them all as being parts of the same thing. To be personal about it, I am surprised to find I am still completely taken by photography. It was possible, when I started to write about photography all those years ago, that I thought this was just a field I was in, and I would move to another field, and then another one. And I’m surprised to find that in dodging and weaving in the way that I have, I have kept my own interest absolutely on the boil the whole time. I’m not in the slightest bit bored by photography or by the functions I take within photography. But I’ve taken a lot of different functions. I’ve never been a picture editor on a magazine for 30 years; I’ve done a bit of this and a bit of that. The CV is very slalom shaped. But I do think that they’re all part of the same thing.

I still believe that photography is by far the most important medium of the latter part of the twentieth century – more important than prose and more important than cinema. No exaggeration. Photography is transnational, it’s transcultural. It is available to five-year-olds, it is available to professors of photography. It’s amazing how it is not a limited medium. No other medium equals it in its efficient transmission of powerful messages – certainly not prose. People are less literate than they were but they are more literate in photographs than they used to be, and that is pretty powerful. One could argue that photography is dropping off a bit from those great heights, and its other cousins are jostling up against it, but they’ve all developed from photography. Video games are derived from photography, as is cinema, and actually quite a lot of journalism too. These huge industries which people don’t think of as being post-photographic, I most certainly do. The fashion business doesn’t make any sense without photography. Photography is absolutely at the core of fashion, which is a billion-dollar industry and has been for years. I see photography as being close to either a key or the key to everything else. ♦

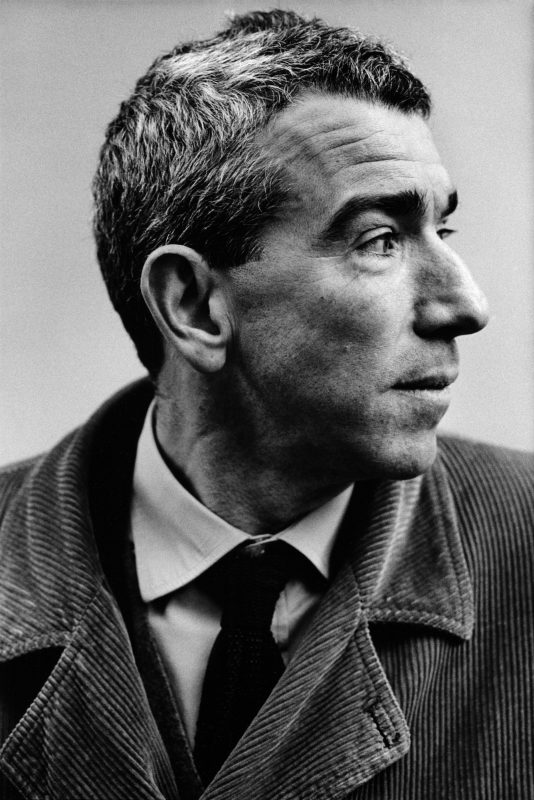

Image courtesy of Francis Hodgson. © Anton Corbijn.