Lebohang Kganye

Dipina tsa Kganya

Interview with Sarah Allen

Lebohang Kganye speaks with Sarah Allen about investigating her own family history, merging photography and theatre as a means to perform the constructed nature of memory and siting new work in the context of a Bristol sugar plantation and slave owner’s home from the 18th century.

Sarah Allen: Much of your photography deals with investigating your own family history. Was there a spark that lit this particular interest?

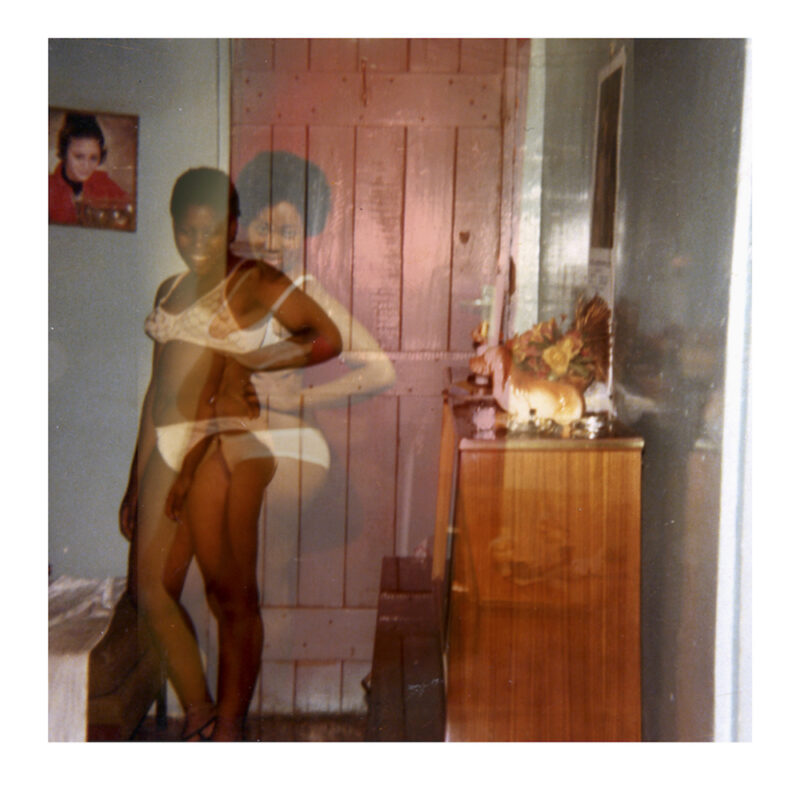

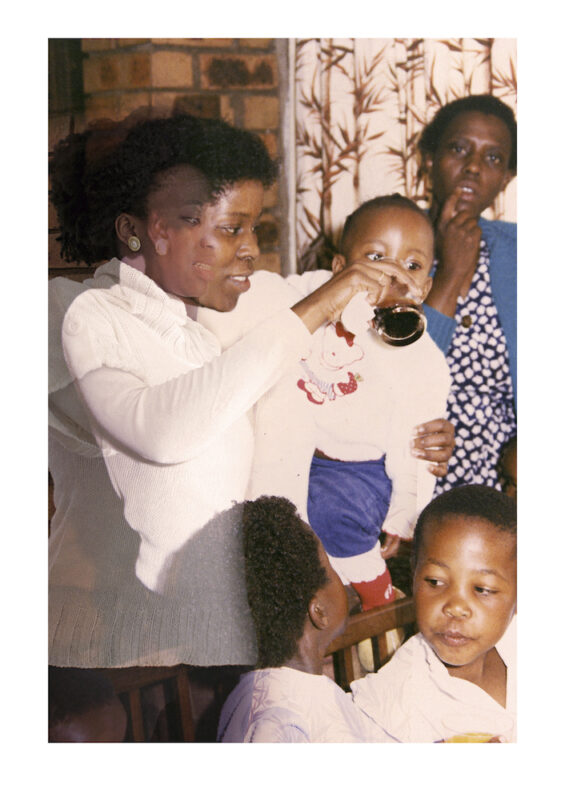

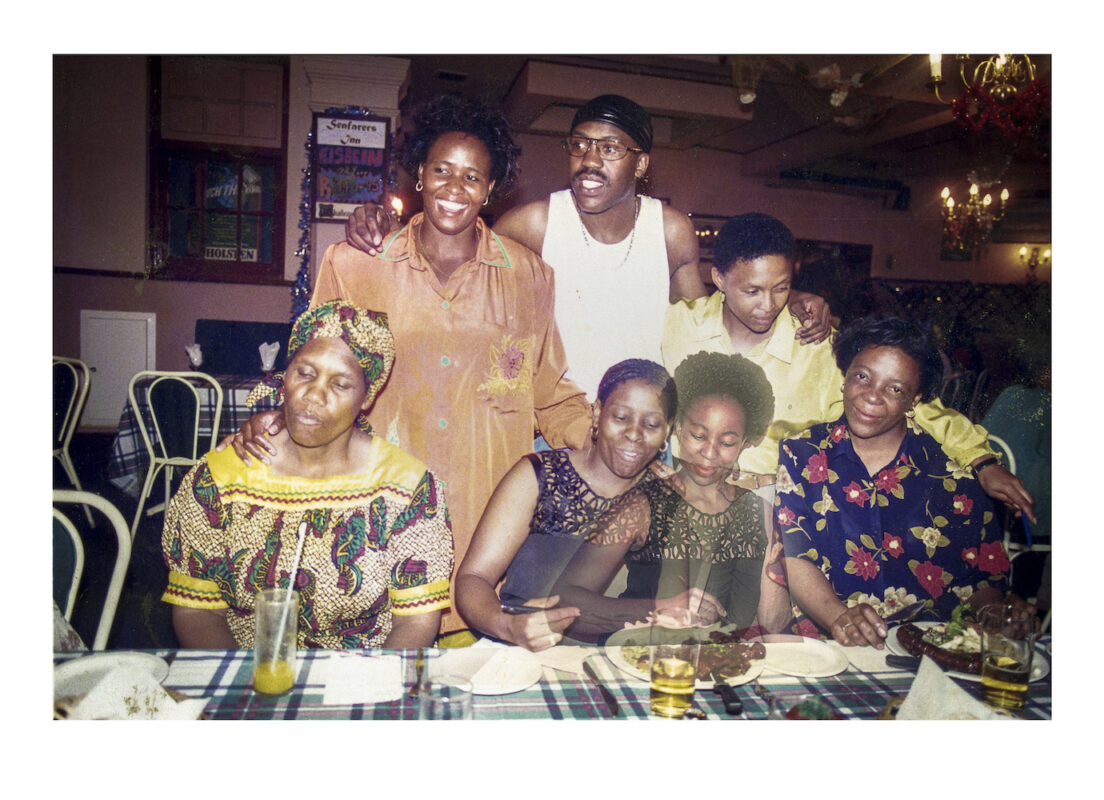

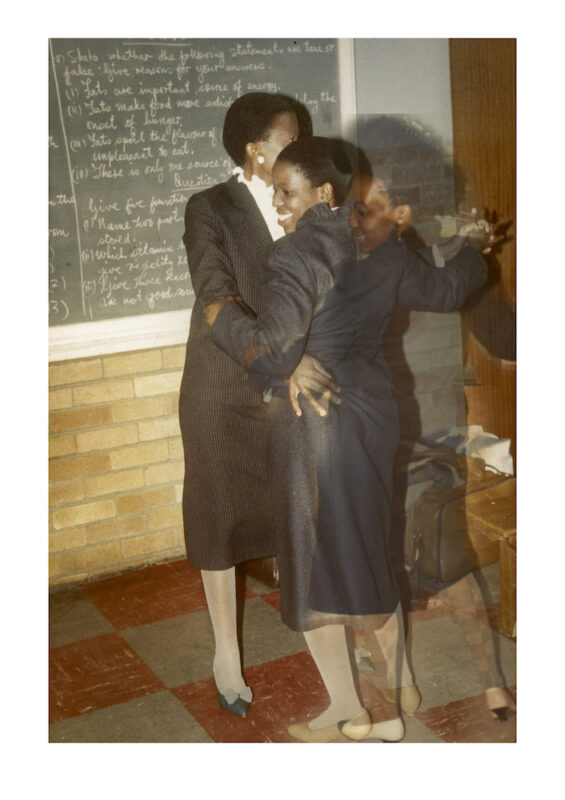

Lebohang Kganye: My mother’s passing ten years ago initiated the need to trace my ancestral roots. She was my main link to our extended family and past since we all now live in separate homes. I had to locate myself in the wider family on some level and perhaps also explore the possibility of keeping a connection with her. Two years after my mother’s passing, I was looking at a lot of her photographs and the more I kept looking, I realised that a lot of the locations these photographs were taken in – the ones I could recognise – were mostly at my grandmother’s yard or somewhere I knew. I went on this journey in search of her. I also realised that a lot of the clothes she was wearing in these photographs of her as young woman were in the house. I then put on her clothes and started going to the locations where my mother had been photographed to restage her photographs and mimicking the same poses to visually emulate my adoption of the role of the mother to my sister after our mother’s death.

In Jacques Derrida’s The Work of Mourning (2001), he discusses the loss of self that takes place when you lose someone you love: a double loss. My reconnection with my mother became a substitute for the paucity of memory through a visual manipulation of ‘her-our’ histories by inserting myself into her pictorial narrative and emulating the snaps of her from my family album. Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story (2013) are digital photomontages in which I juxtaposed old photographs retrieved from the family archives of my mother in her twenties and early-thirties with photographs of a ‘present version of her-me’ to reconstruct a new story and a commonality: she is me, I am her. My mother was my main link to my extended family and history, so her death sparked the need to trace my ancestral roots and locate myself in the wider family to explore the possibility of keeping a connection with her through photography.

SA: It’s a very personal history, but it’s also one that many people can relate to: the loss of one’s mother. This dual sense of both personal and shared histories is also present in the series Ke Lefa Laka: Heir-story (2013). Could you speak a little more about this body of work, and in particular, its focus on histories of naming in South Africa?

LK: My work explores themes of personal history and ancestry whilst resonating with the history of South Africa and apartheid. Ke Lefa Laka: Heir-story documents my personal history and straddles generations of my mother’s family, resonating with the history of South African displacement, in that my family was uprooted and resettled because of apartheid laws and the amendment of land acts. The narrative, as chronicled by my grandmother, of my family moving and creating temporary homes in different locations during the apartheid era as a result of dislocation and land dispossession of Black South Africans had a direct impact on the identity of my family and on the family name. Our family name shifted in an attempt to identify with the different social and physical spaces in which my family lived, or because of negligence in the recording of names by the civil registrar at the South African Department of Home Affairs. Fragments of the name are embodied in the multiple versions of the name, starting with how it is said, how it is pronounced and finally how it is spelled: Khanye, Khanyi, Kganye and Khanyile. People often couldn’t record their own names (or dates of birth) and, sometimes, the official modes of documenting were recorded incorrectly on documents such as birth certificates, identity cards and passports: documents that attest to identities and histories, and thus resulting in an alteration of oral histories and names. Names as a historical, social product highlight the history of naming as a device against illiteracy and the lack of birth records in South Africa through names associated with historical events, which served as a register to estimate the ages of the name bearers. Names can also be chosen at random and evolve, and, indeed, the tracing of the name of ‘Khanye’ demonstrates how this surname changed over time, responding to a family’s history and migration, as they are influenced by the socio-political and economic impacts of colonialism and, then, apartheid South Africa. The work speaks to the process of migration and touches on the subject of genealogy, which transformed family structures and networks in and around Southern Africa.

SA: Did the process of working on this series teach you anything about identity in general? Did you find any form of resolution?

LK: I was thinking about the notion of ‘Identity’ within the South African context and one embraces individual identities independent of collective identities. Identity remains a space of extreme contradictions – in a way an experiment; it is a mixture of truth and fiction; a blending and clashing of gathered histories and stories, a malleable entity with the pretence of being fixed. However, it presents an interesting challenge in the way that complicates individual agency. Identity cannot be made fully tangible just like the products of a camera; it is a site for the performance of dreams and the staging of narratives of contradiction and half-truths as well as those of erasure, denial and hidden truths. Identity, therefore, becomes an orchestrated fiction and a collective invention. Achille Mbembe makes a profound statement on our perception of the world in his introduction to the Africa Remix (2007) catalogue: ‘Our way of belonging to the world, of being in the world and inhabiting it, has always been marked by, if not cultural mixing, then at least the interweaving of worlds, in a slow and sometimes incoherent dance with forms and signs which we have not been able to choose freely, but which we have succeeded, as best we can in, in domesticating and putting at our disposal.’

People have different reasons for trying to know their family histories or past. I chronicle my family name using various modes of presentation and archival materials in the form of family albums, interviews with individuals involved to weave family narratives that would otherwise not have a platform or form beyond the experiential. Both methods of data collection often lead one to an approximate truth. An individual’s memory about a particular event may include political and personal bias. On the other hand, raw artefacts such as photographs have the inherent limitation of speaking to context. Both these flaws open up an opportunity to generate my mythology and fluid story telling.

SA: Is that sense of photography’s inherent limitations one of the reasons why you work across media, for example with film and sculpture?

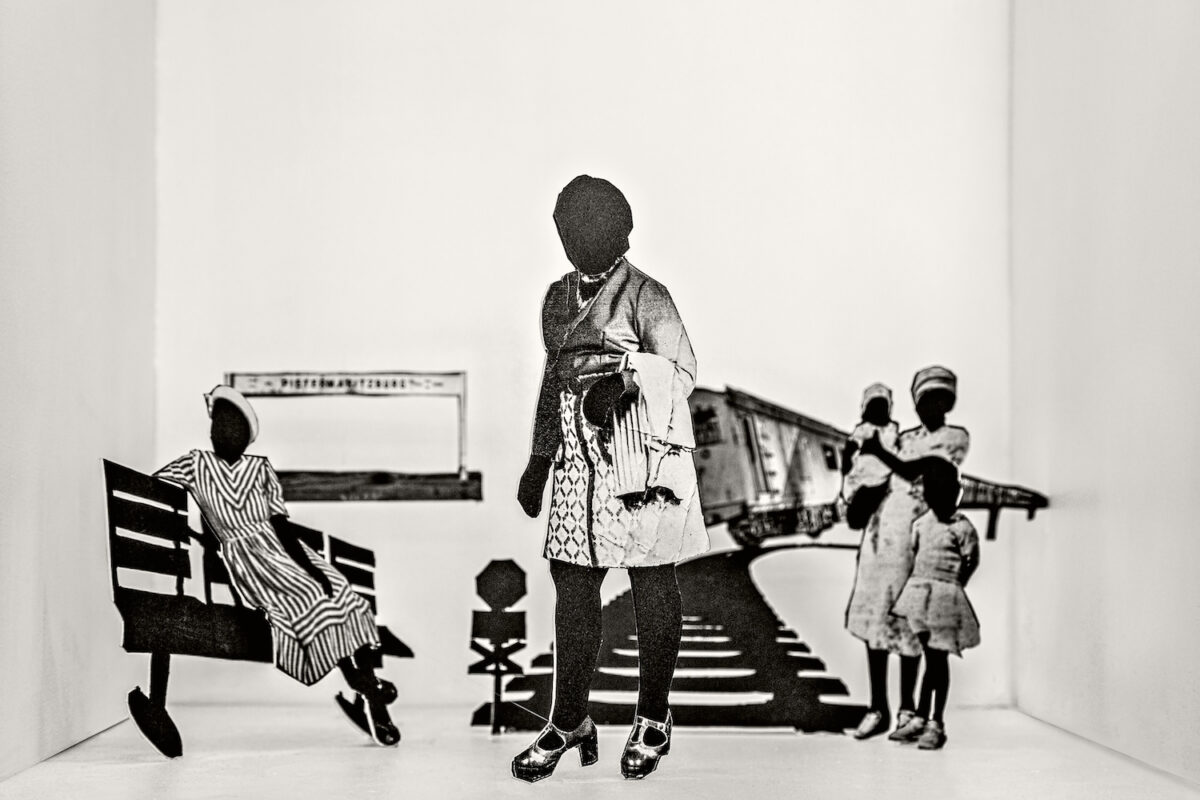

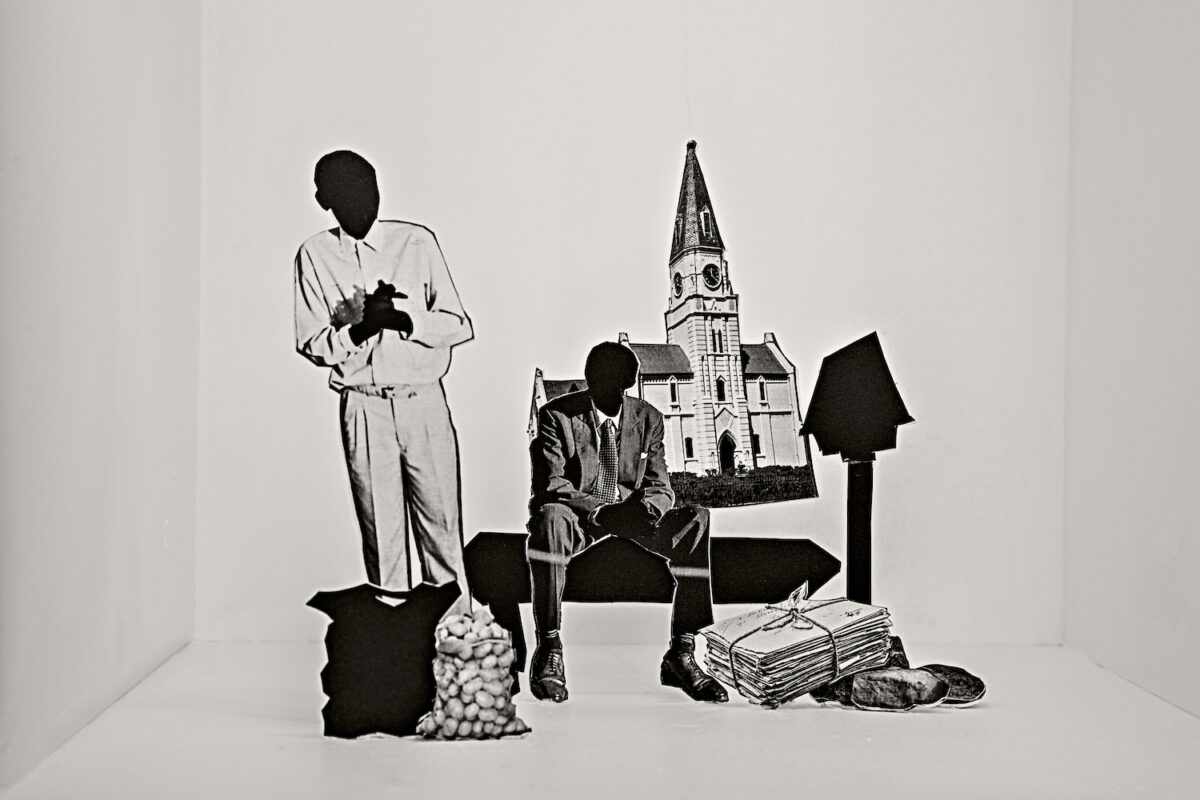

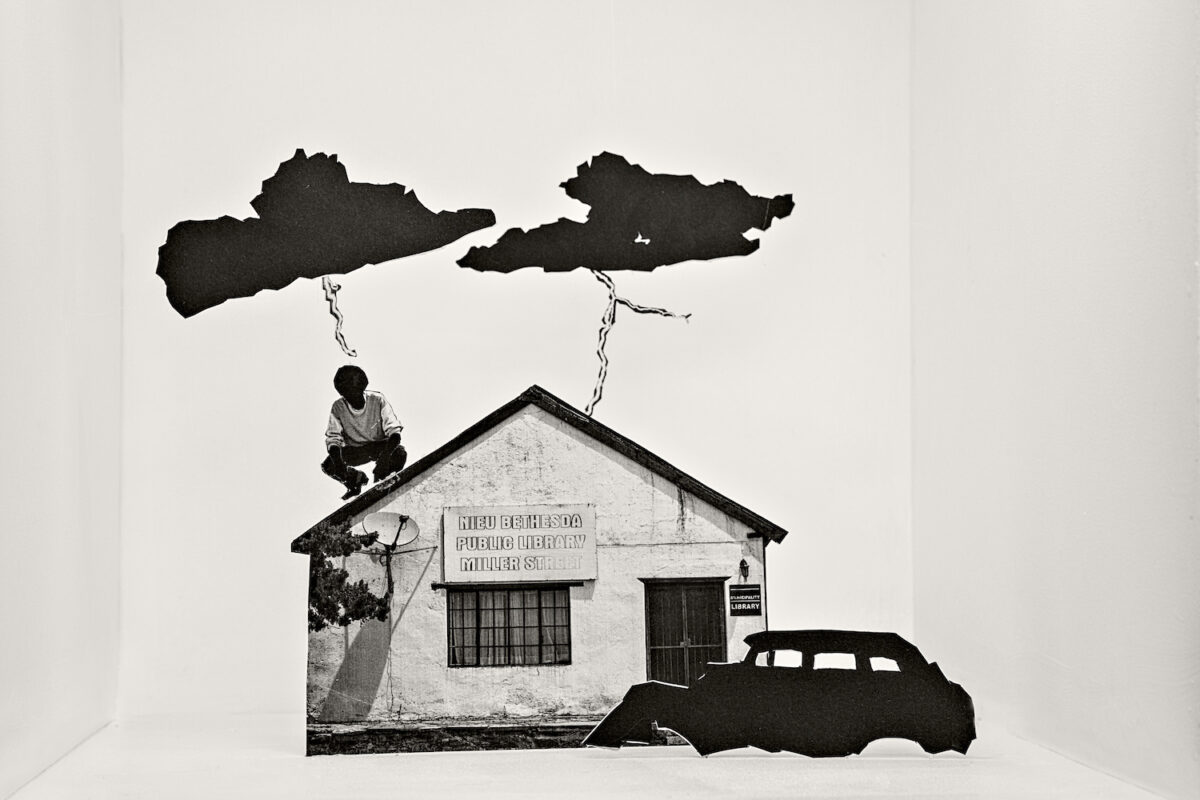

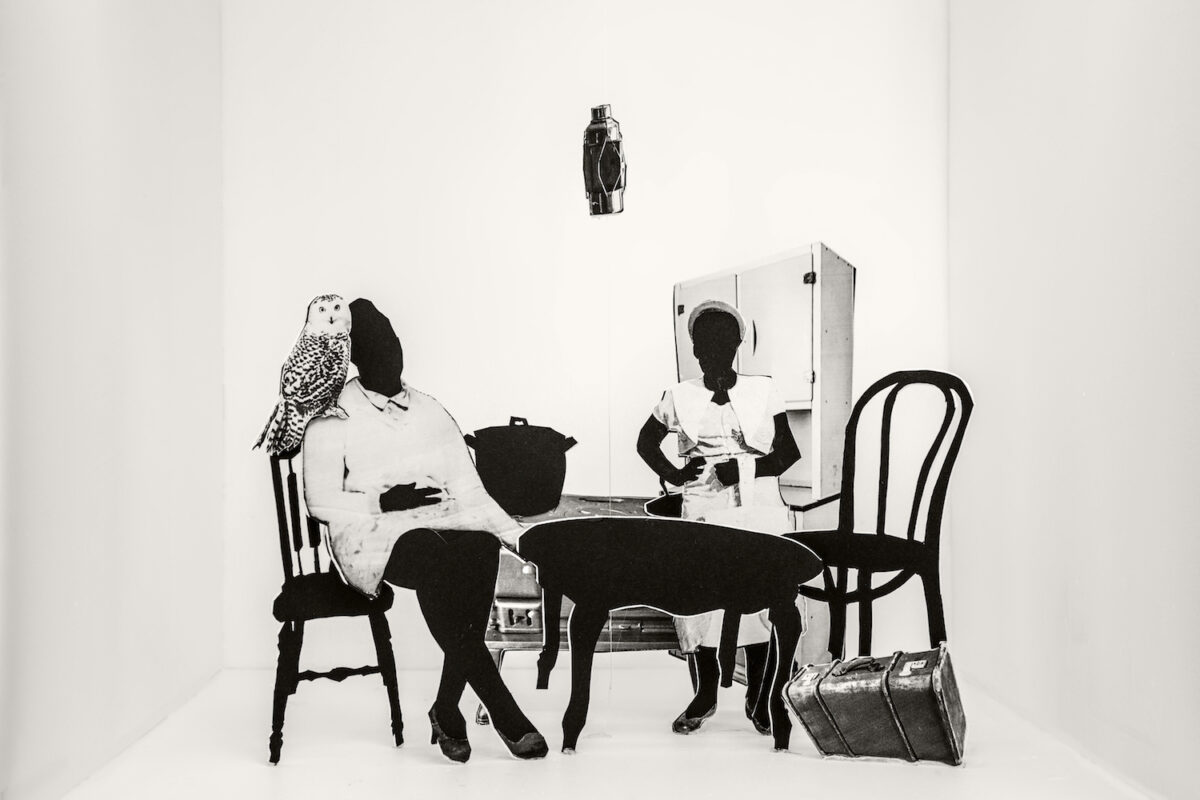

LK: My practice has always tried to counter this idea that the photograph is instantaneous. Revealing the different elements of the construction of a photograph as an authoring of my own history is an important part of my practice. For the animation film Pied Piper’s Voyage (2014), I worked with a studio set, with life-sized cardboard cut-out images which look like flat-mannequins. I inserted myself to construct a visual narrative in which I meet my late grandfather, who passed away before I was born. In these fictive narratives, I am the only ‘real’ person, taking on the persona of my grandfather, dressed in a suit, a typical garment that he often donned in family photographs. These different modes speak to how memory and history intersect and what their role is within a photograph. Over the last seven years, my practice has been investigating memory as material. My recent works implement the act of cutting, folding, pasting and assembling medium or life-sized elements to construct each scene. These moveable paper elements of cardboard cut-outs create the illusion of a theatre set and proposes photography both as practice and object. In a similar way to figures and objects in a dollhouse, each cut-out creates the illusion of an entire world. They look like they could be moved, changed or shifted. I wish to emphasise the fabricated nature of history and memory in this work: how the visualisation of an event always induces an element of creation, experimentation and error; an on-going construction.

SA: I am also really interested in the performative aspect of your work – the reference to set design and theatre but also the idea of performing the self and one’s own history. Could you speak a little more about that?

LK: In the process of recreating the family photographs, particularly my mother’s, I began to consider the ways in which these photographs were a performance, allowing the subjects to inhabit a range of personas. Most of the snapshots were made before I was born in 1990, at my grandmother’s house. My mother had such limited access to cameras at that time. (There was one photographer in each neighbourhood in the township. He’d be cycling by and you’d set a date for him to come and take a photo of you dressed in your Sunday best.) With the opportunity to make photographs so limited, every picture became more powerful, giving them the opportunity to plan their outfit, pose and location. In my creative practice, photography is used as a way to recreate moments that I have never myself experienced. I have begun working with theatre scripts such as in my body of work Tell Tale (2018), which is mainly inspired by Athol Fugard’s play Train Driver (2010), set in Port Elizabeth, and a chapter in Lauren Beukes’ Maverick (2004) about a character named Helen Martins, which Athol Fugard writes about in his play Road to Mecca (1985), set in Nieu Bethesda, in the Karoo, Eastern Cape.

My new project titled In Search for Memory is indicative of both my primary use of photography as a malleable medium ongoing interest in the very construct of memory. Initially developed in 2020 as a set of collage prints on inkjet paper, In Search for Memory makes use of literature as primary source material. The images produced are inspired by Malawian writer Muthi Nhlema’s science fiction novella TA O’REVA (2015). The first iteration of this project includes six ‘scenes’ assembled with inkjet print cut-outs staged as dioramas and will later extend in the form of a large-scale mechanised pop-up book installation titled Staging Memories. I will produce a large-scale book installation exploring the materiality of photography in dialogue with the disciplines of theatre and literature and to position the ‘non-fictional’ assumption of photography in conversation with the ‘fictional’ world-building capacity of theatre and literature. This interdisciplinary modality introduces a fluidity of disparate temporalities and imaginaries to the storytelling and performative gestures that continue to inform my practice. I will create an installation that visually references a set of mise-en-scène.

SA: I’m also interested in how you engage with sound – the oral and the aural – in your work. That is, both the importance of oral histories, but equally thinking about the use of sound in your video work. For example, I know your latest commission deals with the tradition of praise-singing.

LK: My latest commission by Bristol Photo Festival 2021 is a black-and-white, three-channel video installation titled Dipina tsa Kganya (2021). It features two performances informed by the notion of healing, enacted through acts of naming and cleansing. The word dipina means ‘songs’ in my mother language of Sesotho. The song referred to is that of my family clan names, traditionally passed down through oral tradition. Additionally, the Sesotho word for ‘light’, kganya, is in the etymology of my last name: Kganye. A central visual component is the lighthouse featured in the middle channel of the video work. A light beam, in perpetual motion, casts light onto the surrounding ocean scene and in turn creates shadows in the two peripheral channels of the work. In the first or left video channel, a lighthouse keeper appears as a custodian of this light, tending to it by continually cleaning the bulb: a light source that symbolically guides those lost at sea. The song featured in the work (composed by musician Thandi Ntuli) plays from a large, custom-built Polyphon music box, which is hand cranked in the third or right video channel. These performative gestures are in conversation with the southern African practice of the ‘praise-singing’ of clan names as a way of passing down the origins of the family story as an act of resistance to historical erasure, to ensure its unwritten continuity. My research inquiry began with investigating the origins of my family name ‘Khanye’ and the history of naming. This led me to exploring my family’s Direto, a Sesotho term for clan names or praise poetry of allegorical stories passed down orally from generation to generation, which a clan of people defines themselves by. In the South African context, every Black surname has its own clan poetic praises; this self-praise poem is an identification with one’s family and lineage group. These anecdotes of praise are of heroism and often expressed at important social groupings. This oral tradition of recitation gives a stage to introduce oneself to the gathering and assert oneself through an embodiment of historical events, social experiences and family lineage. It is an evolving vernacular culture of Southern Sotho oral histories embedded in the performance of naming and self-narration, as a testament of family identity in the Basotho culture. Others are derived from the names of our grandfathers and siblings from the father’s side of the family but as my father was not part of my life, I inherited my mother’s surname.

SA: As part of this commission, your work will be displayed at the Georgian House Museum. What is at stake for you when engaging with a British institution such as this?

LK: My initial reservations with the commission were deeply tied to the Georgian House Museum’s own histories. A historical museum speaks to a very specific history and context that has been identified as worthy to conserve. The museum provides visitors with the opportunity to discover what a Bristol sugar plantation and slave owner’s home might have looked like around 1790. Its 11 rooms, spread over four floors, are used to reveal what life was like above and below stairs, from the kitchen in the basement where servants prepared meals to the elegant formal rooms above. Using themes of people, home, family, ancestry, slave-trade and social hierarchy that are particular to this historically rich structure, we draw closer to the inhabitants, their stories and the social complexities of the house.

SA: What has been the greatest challenge of the commission?

LK: The exhibition was meant to open to the public in Bristol at the Georgian House Museum in April 2021, but will only be opening in April 2022 due to the pandemic.

SA: What has the past year of pandemic meant for your practice and what is the most important lesson you learned during this time?

LK: The anxiety that came with being an artist during a pandemic forced a shift in my perspective with regards to my practice. The work I have birthed during this time is so deeply spiritual.

SA: Thank you, Lebohang. It has been a pleasure to speak with you. ♦

All images courtesy the artist and the Georgian House Museum, Bristol © Lebohang Kganye

Dipina tsa Kganya will be held at the Georgian House Museum in April 2022.

—

Lebohang Kganye incorporates the archival and performative into a practice that centres storytelling and memory within a familial context. In 2022, a solo exhibition of Kganye’s newly commissioned works will be presented by the Georgian House Museum as part of Bristol Photo Festival 2021. Her solo exhibition The Stories We Tell: Memory as Material (2020) was staged at George Bizos Gallery at the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg, South Africa. Notable awards include the Grand Prix Images Vevey (2021–22), Paulo Cunha e Silva Art Prize (2020) and Camera Austria Award (2019). She was also selected as the finalist of the Rolex Mentor & Protégé Arts Initiative (2019).

Sarah Allen is Head of Programme at South London Gallery. She was previously a curator at Tate Modern, London where she curated or co-curated Zanele Muholi (2020); Sophie Taeuber-Arp (2021); Nan Goldin (2019); The Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art (2018), as well as collection displays including Mark Ruwedel (2018); Irving Penn (2019) and David Goldblatt (2019). Outside her role at South London Gallery, she sits on the Board of Directors of Belfast Photography Festival.

Images:

1-‘Ka 2-phisi yaka e pinky II’, from Her-story (2013).

2-‘Ke le motle ka bulumase le bodisi II’, from Her-story (2013).

3-‘Moketeng wa letsatsi la tswalo la ho qala la moradi waka II’, from Her-story (2013).

4-‘Ngwana o tshwana le dinaledi II’, from Her-story (2013).

5-‘Re intshitse mosebetsing II’, from Her-story (2013).

6-‘Re tantshetsa phaposing ya sekolo II’, from Her-story (2013).

7-‘You couldn’t stop the train in time’, from Tell Tale (2018).

8-‘The nameless ones in the graves’, from Tell Tale (2018).

9-‘Helen’s father grazing his goats’, from Tell Tale (2018).

10-‘Farmer selling Sneeuberg potatoes’, from Tell Tale (2018).

11-‘Johannes Hattingh struck by the bolts from above’, from Tell Tale (2018).

12-‘Never light a candle carelessly’, from Tell Tale (2018).

13>15-Still from Dipina tsa Kganya (2021).