Michael Etzensperger

Normal Viewpoint, No Other Than The Direct Frontal View

Essay by Martin Jaeggi

The title of Michael Etzensperger’s series of photographs Normal Viewpoint, No Other Than The Direct Frontal View has a decidedly authoritarian ring to it, one that seems at odds with the photographer’s delight in pictorial invention. It is in fact a quote derived from an 1890 text on how to photograph sculpture by the Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin (1864-1945), a pioneer of formalist approaches to art history.

Wölfflin championed the assiduous study of artworks’ surfaces and formal characteristics in order to analyse art history as a succession of clearly delineated styles that take precedence over the individual artist. Most notably, he investigated the shifts of artistic vision from Renaissance to Baroque. His emphasis on the close, visual study of artworks led him to advocate the use of slide projections in teaching art history yet also instilled in him an awareness of the problems of photographic representation. In his essay on how to photograph sculpture, he lombasted photographers who took artistic license when instead they should, he said, be merely documenting and not using it as an opportunity to showcase their ingenuity. In short, he proposed a strict set of rules, based on rigorous formal analysis, which ultimately set out to curtail the creativity of the photographer. Etzensperger explains: “[Wölfflin] supported the thesis that a sculpture cannot be photographed from any given angle, but that it requires the correct viewpoint of its viewer – in general the front view. From this position, the viewer needs one single glance to see the sculpture’s shape, contour and proportion at its highest point of perfection.”

Michael Etzensperger developed an interest in sculpture during a stay in Brussels, where he discovered a book by the conceptual artist Marcel Broodthaers and photographer Julien Coulommiers, Statues de Bruxelles, which showed the city’s abundant sculptures from unusual angles – coincidentally taking the very approach that Wölfflin so passionately attacked. The publication inspired Etzensperger to search for unusual and playful ways to register sculpture that would highlight the photographic illusionism at work via that very act of the representation – the slippery interplay of sculpture’s physicality and the flat, surface qualities of photography.

Hence, it is no surprise that Wölfflin’s dogmatic, yet persuasively argued essay piqued Etzensperger’s interest when he chanced upon it as part of his research on interdisciplinary practice. Etzensperger picked up on the fact that at the heart of Wölfflin’s treatise was the proliferation of photographic art books that existed around the turn of the century – status symbols for a bourgeois audience keen to display their education and cultural sensibilities. Etzensperger began to collect early twentieth century photobooks on sculpture and used them as source material for collages that he would then rephotograph. Reinterpreting Wölfflin’s text, Etzensperger creates new, fictional sculptures from already ‘standardised’ reproductions, cannily shifting back and forth between three-and two-dimensionality and pushing photography’s illusionism one step further into the virtual.

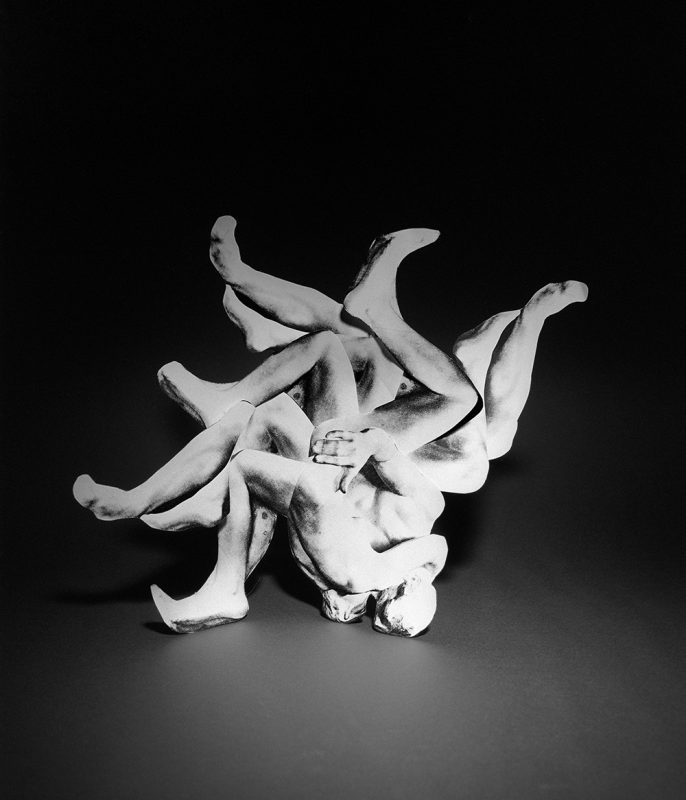

In eight large-format black and white photographs, Etzensperger stages delirious variations on iconic sculptural topoi. In Clothing, he shows a headless figure submerged in a waterfall of folded fabric. Whereas in classic sculpture the arrangement of folds is a discreet sign of mastery, Etzensberger transforms it into an all-encompassing excessive swirl at odds with any classical ideal. The same happens to the limbs of lovers that resolve into a fleshy wheel turning upon itself. In Torso 1-3, classical torsos, epitomes of measured beauty, are cut up into strangely disfigured shapes that are reminiscent of Expressionism’s violent, fractured representations of the human body, while the edgily collaged fragments of the breastfeeding Virgin Mary seem to nod to Cubism. In Atlas and Stone, Etzensperger tackles the perennial question of the relationship between stone and sculpture. But whereas in a standard narrative the sculptor heroically masters the slab of stone, here its weight and materiality reasserts itself in Etzensperger’s collage, defeating the will to form. They expose sculpture as illusionary a medium as photography.

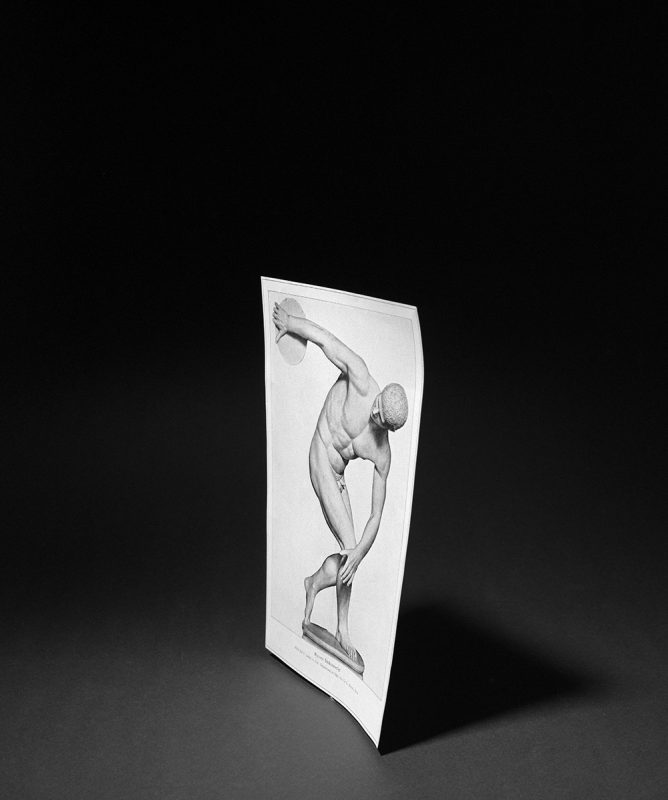

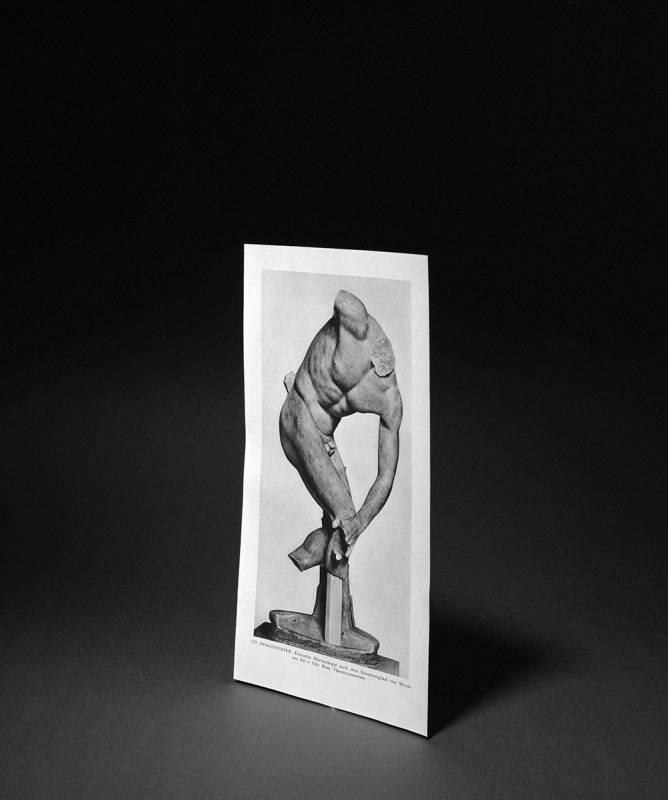

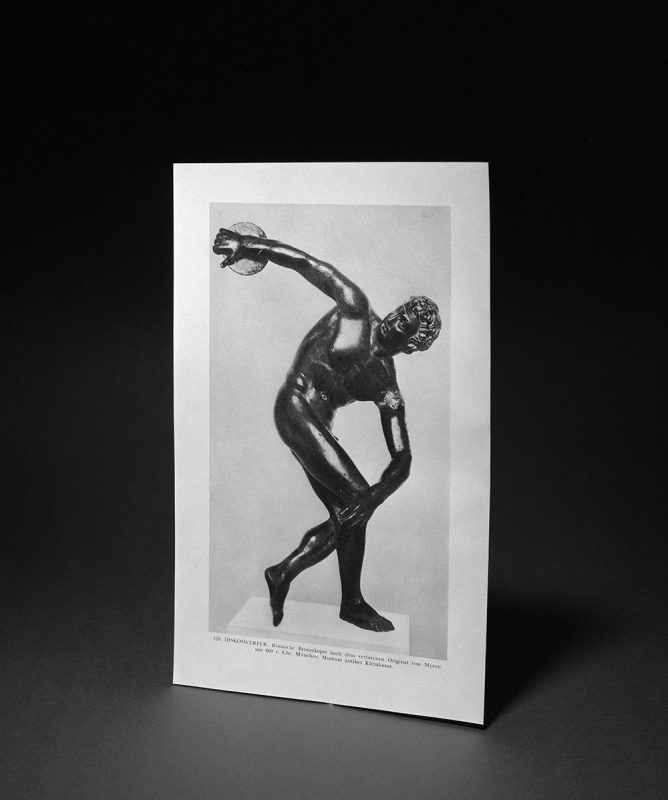

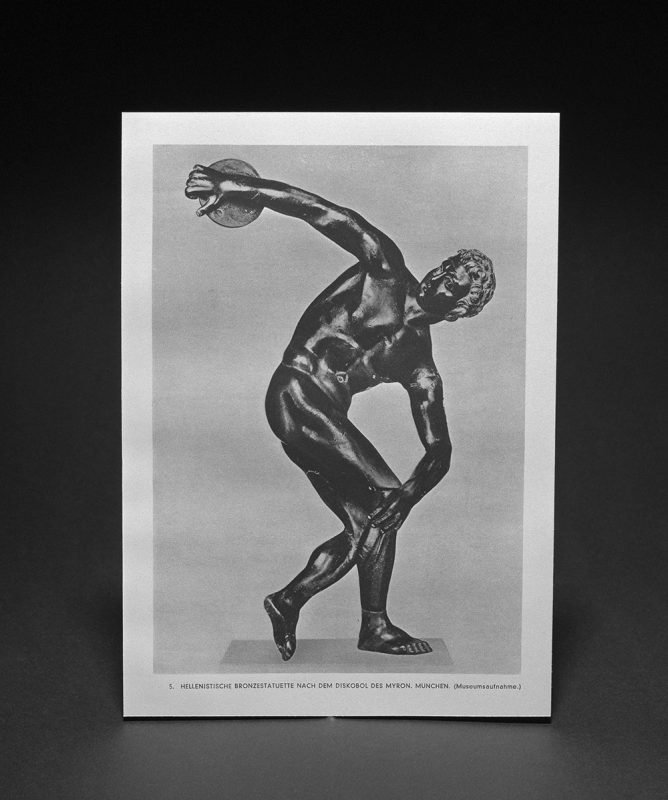

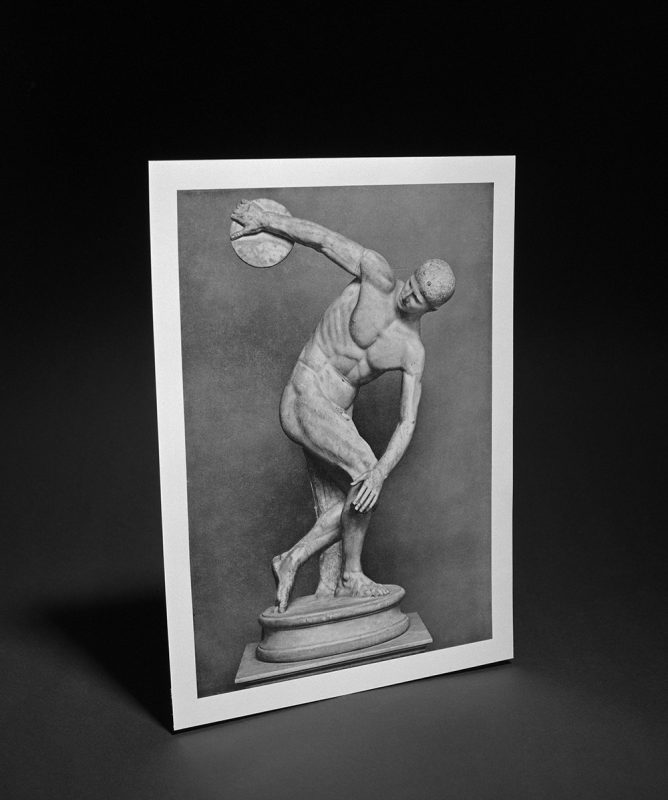

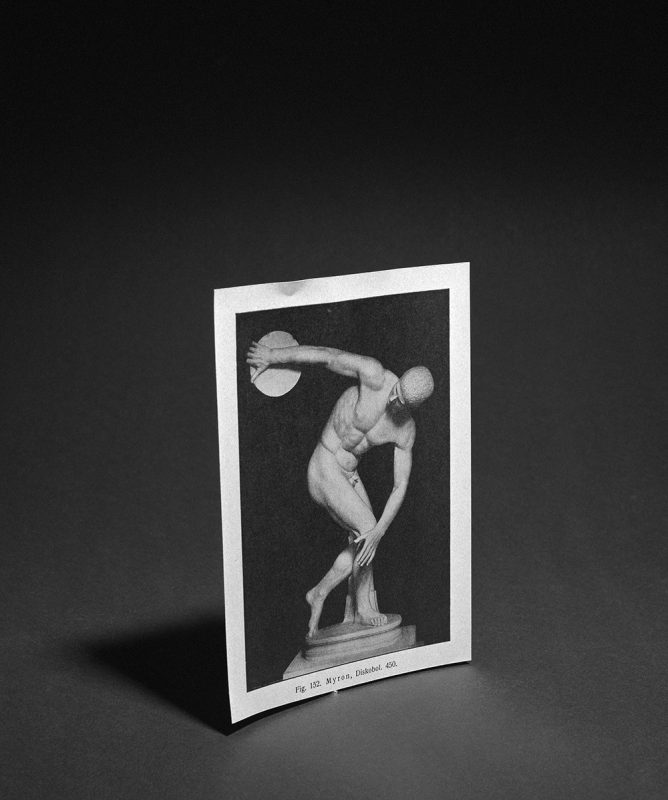

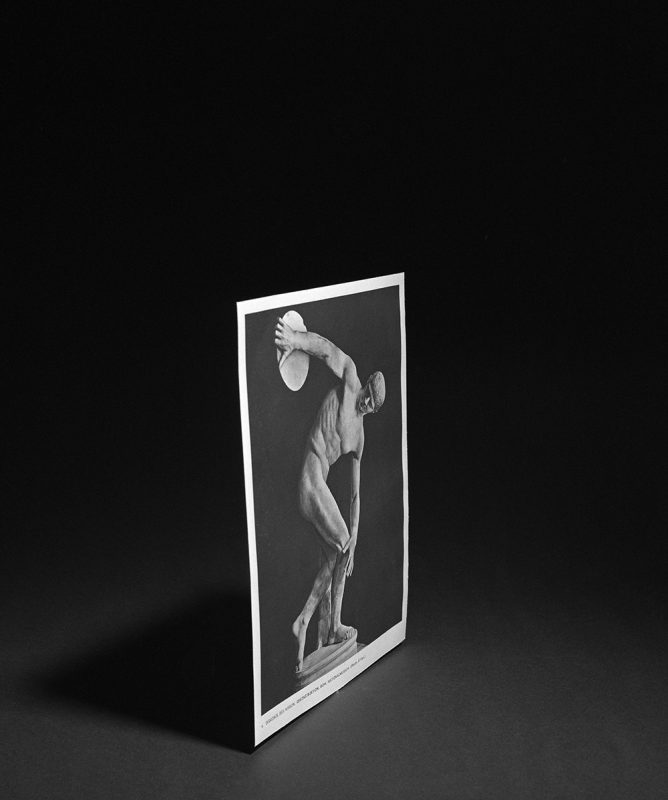

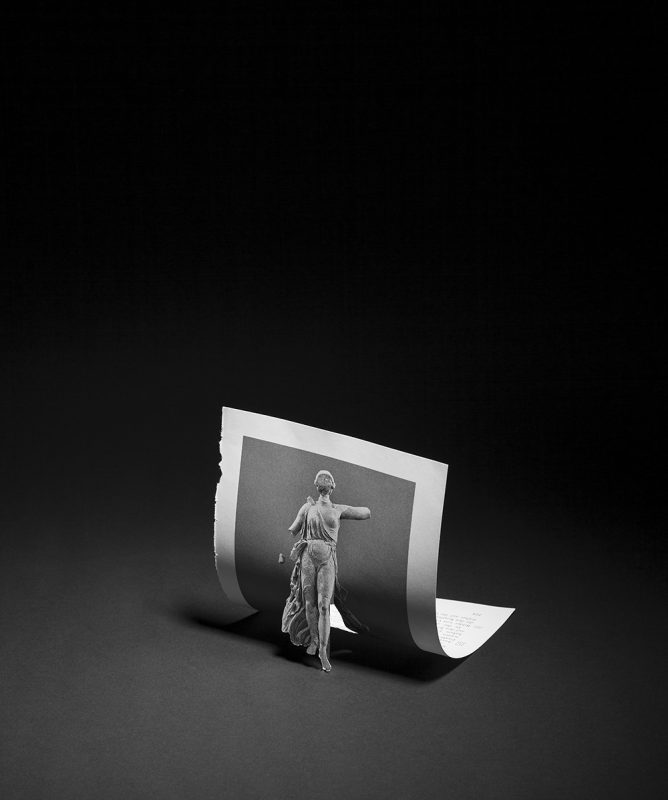

The illusionism of a sculpture’s photograph is always a second-degree experience that loses any vestiges of referentiality in Etzensperger’s collage. These questions also resurface in two mini-series, Nike and Discobolus. By partially cutting out several reproductions of the Nike of Samothrace and arranging them in a manner suggesting that the goddess is literally stepping of the page, Etzensperger refers to countless animated film scenes in which characters step off the stage set, thus cajoling the venerable Nike into a cartoon-like scenario. In Discobolus, Etzensperger approaches the question of reproduction from two angles. This relief of a disk thrower is considered one of two masterpieces by the ancient Greek sculptor Myron of Eleutherae, several copies of which are extant while the original has disappeared.

Before the invention of photography, sculpture was disseminated by means of copies, which were highly-sought after. The cult of the original enters rather late, further abetted by the rise of photography, which took over the function of the copy. In line with this, Etzensperger produced seven photographs of different copies of the disk thrower, which all conform to Wölfflin’s standards, yet are photographed from oblique perspectives and therefore suggest spatial movement as if to poke fun of the reproduction’s proper intent.

As a result, Normal Viewpoint, No Other Than The Direct Frontal View engages in both a dialogue with photography and art history, highlighting their points of intersection as first outlined in Wölfflin’s essay. It plays out sculpture’s simulcra against that of photography, creating a hall of mirrors where various means of reproductions reflect off each other. Yet by highlighting artifice, the original referent, the human body, comes back into focus. Since antiquity Western sculpture has defined our ideals of the body beautiful, which have frequently come under attack and reconsideration in various twentieth century art movements. Ultimately, Etzensperger uses photographic fragments of classical sculptures to create gently subversive counterparts, informed by modernism’s reframing of the human figure by way of fragmentation and distortion. Etzensperger superimposes the two contrasting approaches in his photographs and thus stimulates questions about this radical break in art history and, just as importantly, on the status of sculpture today. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Michael Etzensperger (Installation View: Michael Etzensperger & Sarah Hablützel)

—

Martin Jaeggi is a Swiss-based critic and curator. He is a lecturer in the Department of Art and Media at Zurich University of Arts.