Piotr Zbierski

Push the Sky Away

Book review by Max Houghton

My eyes deceive me sometimes. I look at an image and see only the negative space, or decipher a creature or shape that it is not really ‘there’. I like to think my perception is enriched by the play of this optical unconscious, and that my sustained impulse towards the image is borne of such mis-looking.

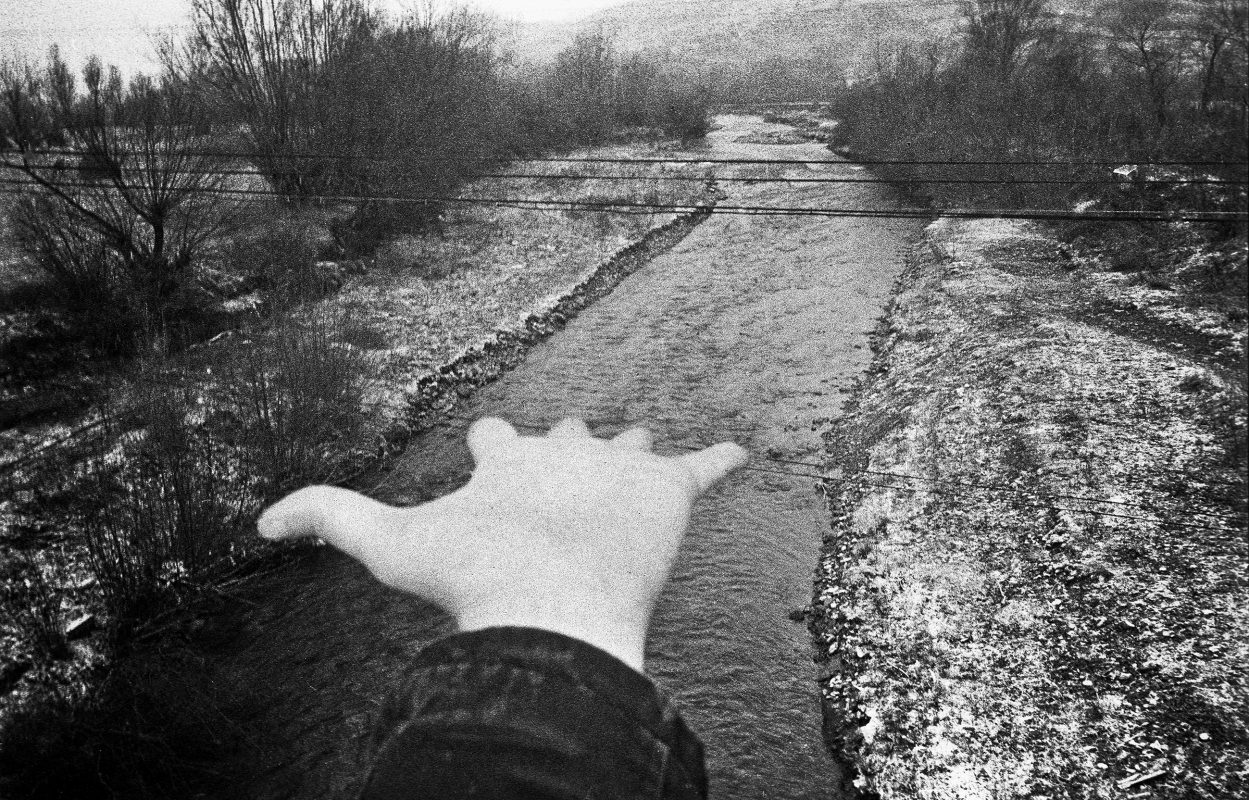

The images created and sequenced by Piotr Zbierski amplify these visual glitches; his preference is for cameras that in some way distort the image. The ensuing instability of the image is used as a strategy here, to transport the viewer into the realm of the senses or emotions; to fold us in. Photography permits special access to this non-geographical place, Zbierski believes, and with Push the Sky Away, an ambitious book published by Dewi Lewis, he shows us the magic of the image. Or, at least, how the image can help us connect to such concepts, and to ritual, myth and the stories that bind us.

The title of the collection is shared (coincidentally, I imagine) with an album by Nick Cave, whose music mines the uttermost reaches of the soul. So if we Push the Sky Away, what’s behind it, above it, beyond it? Without the celestial, how would we comprehend our earthliness? What would happen if the sky was no longer our limit, and instead, we dwelt in a house without a roof? For Hamlet, famously, ‘This brave o’er hanging firmament, this majestical roof, fretted with gold fire: why, it appeareth no other thing to me, than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours.’

Zbierski to be sure sees more than pestilence. He focus is towards being (as opposed to not being) and he has pushed on our behalf, to reveal our raw, unfettered selves. His is a play of three acts, or a triptych, which follows an unfamiliar rhythm, as though from a half-remembered dream. He collects fragments from a brutal though sensual present, which he seems to want to connect to a wilder, more spiritual past. He is a wanderer, a photographic Odysseus, collecting images from the wide, wide world. His accumulated knowledge has taught him that images alone vanish from our tenuous grasp, and this book’s power arises from the sequencing; that is its logic. It is as though Zbierski is trying to impart something urgent, using non-verbal language, to those who look.

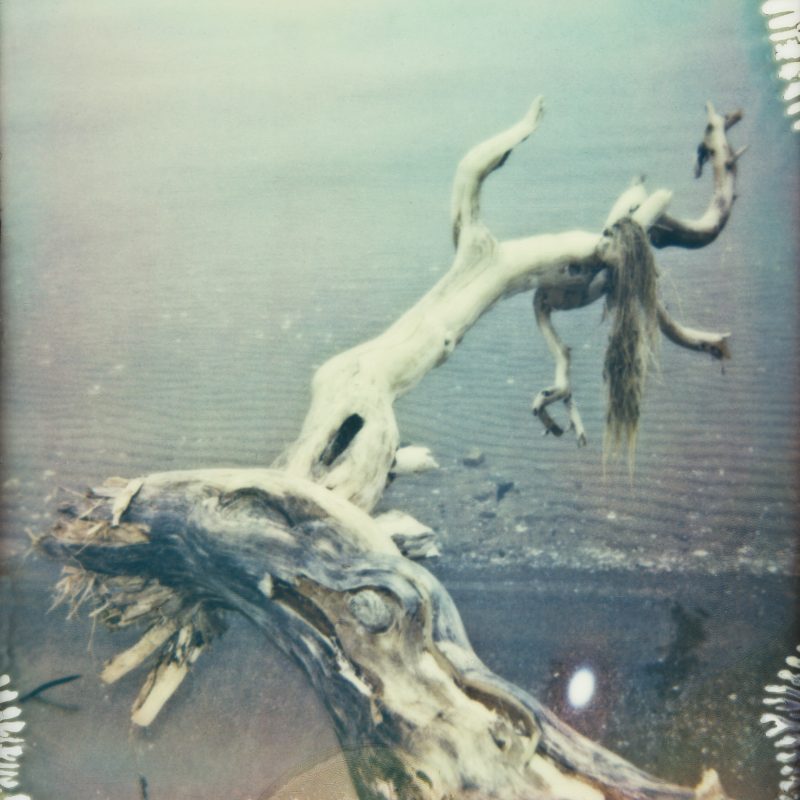

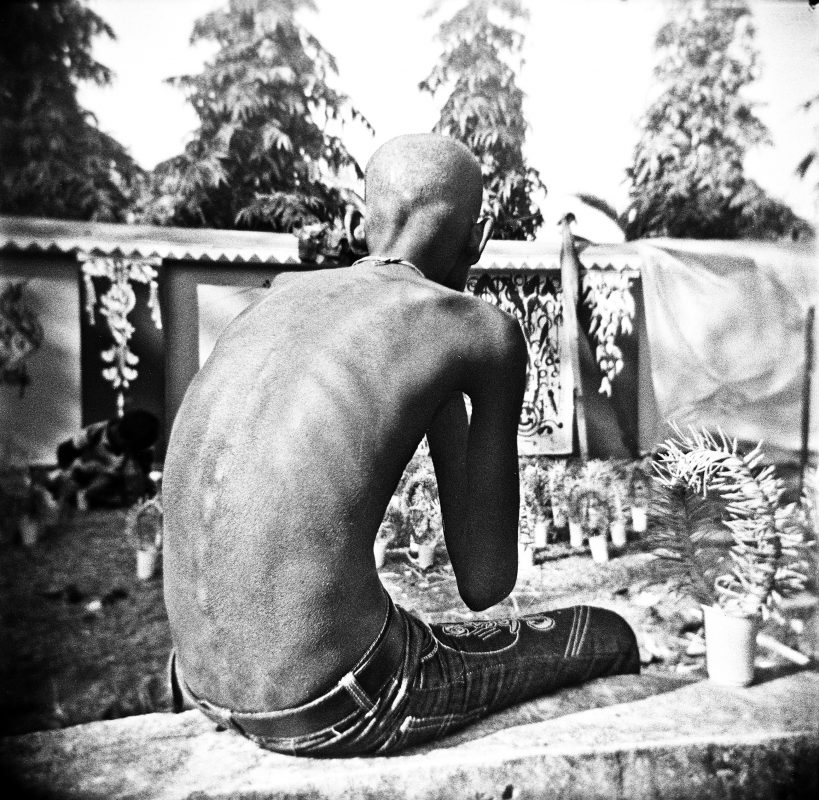

Dream of white elephants, the book’s first section, is populated by black and white images, the first of which is a child, emerging from water, eyes closed – perhaps to symbolise how, wet and alone, we enter the world. Further images flit between playful and perturbing scenes, enticing the viewer to enter to find out more, accessing a space at once strange and familiar. The palette extends to incorporate colour in the second section, Love has to be reinvented. Bodies merge with the landscape; the domestic cat of section one has metamorphosed into a leopard, a cut-out dove floating benignly above its head (unless my eyes are playing tricks). Dogs nuzzle each other, rivers flow, the piper plays his tune. The distinction between people and animal blurs.

Zbierski’s vision becomes increasingly anthropological as the book unfolds, in that images of ritual, of holy men proliferate in the third section, Stones were lost from the base, alongside much more mysterious, fragmentary imagery. An image encased in a circle depicts an inosculation, or an en-kissing, as Robert Macfarlane recently described it, in which tree branches grow into each other. This, and the cover image, also featured across a double-page-spread, operates as some sort of key to this complex work. The cover image looks like an ancient settlement, but is in fact located in his native Poland, and the tents are hewn from local canes and palms. The emulsion on the negative was somehow damaged, resulting in rents swirling across the image, rendering it one of a kind. This kind of play between difference and similarity is also a hallmark of the work, and attests to its unsettling power. Zbierski appears to be reaching beyond religious and scientific interpretations of the world, to a more animistic view, in which everything in the universe possesses a soul.

In Totem and Taboo, Freud brought together animists, obsessional neurotics and children, describing their ‘omnipotence of thoughts’, which, combined with ritual, led to magical beliefs about the impact of their thoughts in the world. He might have included artists into this category, but instead it formed the basis of a later paper on narcissism. This observation is not of course a swipe at Zbierski, but might offer insight into the drive to create per se.

It is surprising in a book of images in this realm to see so much text. The first is a poem by Patti Smith, which I am predisposed to like. Its dedication reads ‘-for Piotr’, leaving my imagination to ponder the nature of the relationship between photographer and high priestess of rock poetry, which would be idle conjecture, or between image and text, which I am better placed to pursue. The poem is pure dreamspeak; conjuring oneiric visions from the depths by locating mental images, and positioning them as links in a chain. In this way, poet and photographer are one. The book also hosts an excellent essay by Polish academic Eleonora Jedlinska, which takes the reader on a philosophical journey through Zbierski’s images, in order to contemplate, among other things, what comprises the sacred, and, equally importantly, what constitutes the profane. Since David Campany created the removable essay, in his outstanding work a Handful of Dust, it seems desirable for all works to have the with/without option. This essay does enhance the experience of the extended photowork, but (how could it be otherwise) also points the reader in certain directions, sometimes away from, the flow of the image. Zbierski’s own introductory essay is thoughtful and interesting, but offers up a doubling with the ensuing chapters of images. As I suggested earlier, he is developing a different kind of language, without words, and must now apprehend his own authorship. Zbierski asks if such elements as pain or ecstasy can be tamed by a photograph. He makes his own question redundant by unleashing the wildness of the image with every turn of the page. After much looking, I am still not sure what it is that I have seen. It makes me want to look again. ♦

All images courtesy of Dewi Lewis Publishing. © Piotr Zbierski

—

Max Houghton writes about photographs for the international arts press, including FOAM, Photoworks and The Telegraph. She edited the photography biannual 8 Magazine for six years and is also Senior Lecturer in Photography at London College of Communication – University of the Arts, London.