RaMell Ross

Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body

Book review by Pelumi Odubanjo

Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body, RaMell Ross’ debut book published by MACK, is a potent visual reminder of the history of black American life, a kaleidoscope of lyricism, and visual and narrative abstraction. Pelumi Odubanjo considers the gravity of what it means to carry such an archive of black visuality.

Pelumi Odubanjo | Book review | 17 Nov 2023

In his debut monograph Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body, multidisciplinary artist, filmmaker and writer RaMell Ross reflects on the landscape and visual scope of the American South, reimagining it through a range of mediums, from large format photography and conceptual work, to film and writing. Journeying through the optical terrains of the region, Ross directs our attention through the everyday environments, bodies and structures which coalesce to form what he terms ‘Spell/Time/Practice/American/Body’. Unravelling these words through the five chapters which form his monograph, Ross invites us to reimagine the ways in which the visual may be used to disrupt our existence, in turn asking us what the black body is able to do, say and reperform when abstracted across land and time.

The monograph stretches over Ross’ interdisciplinary practice, mimicking a musical compilation album as we pace through its mystery and quotidian nature. Commencing with a pictorial account before combined with textual narrative, the story begins with the chapter “Spell”, set in South Country, Alabama, where Ross directed his Academy Award-nominated documentary Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018). In the two photo series that are present in the monograph, Ross documents South County over two different periods, first from 2012 to 2014, and then from 2018 to 2022. Both capture the semi-ruralness of the land using an illuminating approach to photography, extending beyond the physical structures of the environment into intimate, multigenerational layered images of black communities in the American South.

In the opening series South County, AL (A Hale County), Ross plays on the idea of the undetected as he obscures place and person through various visual tricks; with some subjects facing away from the camera with their hoodies acting as figurative silhouettes, some using the parts of cars to fragment their bodies and others tactfully using light and shadow to allude to a slow unveiling of face and body. The series simultaneously inhabits pastoral and urban spaces as Ross repeatedly searches for new ways to abstract his subjects within the American landscape. In one image, titled “Yellow”, we see a young girl crouched down, the bend of her body mirroring the outline of the foliage that surrounds her. The rose bush that occupies the closest point to the camera obscures the girl, refusing to let her be shown in totality, the red petals slowly fading into the image, appearing as small glimmers of red paint flicked across the photograph. The young girl acts as a mediator to the image’s green hues, her small yellow dress delicately draped alongside the cut grass of the meadow, her small white hairclip and yellow hair accessories appearing as if extended parts of the rose bush closest to the camera’s eye. The image intends to draw the viewer directly towards one place: our young subject who rests in a state of adolescence and wonder. The viewer’s vision becomes purposely pixelated as the young girl’s body both fades away into the landscape and is illuminated through the camera’s unquestionable focus on her. This action is mirrored in Ross’ later image “Giving Tree”, where we see another young character with their body bent, facing downwards as they hang from an isolated tree. Again, Ross purposefully dissembles the young body, fragmenting and splintering it as a large branch passes through her abdominal area. The young girl folds herself across the bough, dressed in a loud red shirt that pronounces her against the natural palette of the surroundings. Her draped body appears lifeless, both contrasting and echoing the “still life” of the ongoing scene. This image awakens brutal memories of black bodies in the American South’s past, one where, in Alabama alone, it has been recorded that over 300 black people were lynched from 1877 to 1943 during the Jim Crow era. By draping herself from this tree, this young girl becomes one of the strange fruits as sung by Billie Holiday, forming a peculiar sight in a yet all too familiar setting.

With this latter image, Ross reminds us that, in its simplest form, a tree is not a symbol of terror. And in this scene, this girl is arguably creating her own sense of joy through play. As with the girl in the previous image, she is simply existing, a state that Ross is able to permit through his lens. It is in her imagination and desire to play that Ross captures what it means to reproduce images of black bodies within such landscapes. Ross creates an unease in his photographs that touches on racial history and violence through a blunt approach to image-making. In these ways, Ross positions his characters in an ontological plurality that so much of black life exists within, between past, present and future, living in an abstraction that lends itself to an inverted understanding of documentation. Ross forces his viewers to question the production of images that they are used to observing of the American South, and defends his right to abstraction, creating an expressiveness and lyricism that goes beyond documentation.

Moving towards various mixed-media and writings, Ross’ poetic works are scattered throughout the book. In Ross’ later poem, titled “Slangness”, we observe the interplay between what is textual and what is visual, his words becoming beacons of speech, yielding to the sling of his dialect, stripped to its bare rhythm. Ross’ playful words mirror the writing of poet and theorist Fred Moten, whose poetic verse and approach to black radical theory reopens wounds of blackness in its ontological form, allowing readers to consider what it means to strip blackness to its barest form. This creates space for transformation and transition, as something which exists in between various co-existing spaces and places.

Similarly to Moten’s style of poetic languaging of black social and cultural contexts, Ross uses his images and words to question what it means to exist in both the past and present as a black Southern body. Much of Moten’s work around the making of blackness is concerned with the specific conditions that form what we know as the black body. Looking into and beyond ideas around blackness in its bodily form, Moten is a writer concerned with the ways in which form and formlessness may be co-opted as tools to suggest alternative ways of viewing and understanding black life as it exists in the present. In this, Moten uses a form of voice composed of fragments, scattered across long sequences and varying shapes, a purposely abstracted form. His words draw you in, and ask you to read through the lines, with language serving as a means to both disrupt and resist expectation.

Ross’ words and imagery are activated through a vortex of abstraction, both in its formlessness and its form, as he allows words to take on new meanings within readings of his work. Similarly to Ming Smith and Roy DeCavara, photographers who leaned into abstraction to create images that enact the constellation of black life that surrounded them, and much like Moten in his writing, Ross uses language to create an inseparable dialogue that meditates our understanding of blackness in the American South. Most aptly seen in his “Black Dictionary (aka RaMell’s Dictionary)”, Ross uses abstraction to resist the system of capture, both linguistically and visually, recognising the role of the linguistic historical subjugation, and freeing them through a lively interplay of idiolect and dialect.

What is it that a black object does? What is blackness able to do in its abstraction? In Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body, Ross testifies that it can reclaim and free you. Occupying the chapter “Practice” is a documentation of Ross’ film Return to Origin (2021), a remarkable conceptual work in which the artist freight ships himself into a 4 x 8 ft box, a reference to Henry Brown who shipped himself to freedom in 1849. In this re-enactment, Ross uses historical references and filmmaking to create a conjunction between the past and present. In turn, Ross challenges us to reorient our understanding of “black objects”, and how through material, method and ways of being in the world, we may build our paths to freedom.

There is an argument that the mass volume of works included in this book causes it to wander at points, and in places risks losing its sense of narrative. However, it is through this abundance of material that we see the gravity of what it means to carry such an archive of black visuality. Ross’ work positions itself as a vital visual reminder of the history of black American life, a kaleidoscope of lyricism, and visual and narrative abstraction. ♦

All images courtesy the artist © RaMell Ross.

Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body is published by MACK.

—

Pelumi Odubanjo is a curator, writer and researcher based between London and Glasgow. She currently works as the Assistant Curator for Glasgow International, having previously held positions as a Curatorial Assistant at the Serpentine Galleries, London, and as Studio and Programmes Assistant at V.O Curations, London. Odubanjo has curated for festivals and institutions including Photo50 at the London Art Fair, Photo Oxford, Tate Exchange at Tate Modern, London, Brighton Photo Fringe and the Black Cultural Archives, amongst others. Her writing on contemporary photography, art and culture has appeared in Magnum Photos, New Contemporaries, Artillery Magazine, Photoworks and Photo Fringe.

Images:

1-RaMell Ross, “Open”, from South County, AL (A Hale County) (2012–14), from Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

2-RaMell Ross, “Man”, from South County, AL (A Hale County) (2018–22), from Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

3-RaMell Ross, “Ladrewya and Michelangelo”, from South County, AL (A Hale County) (2012–14), from Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

4-RaMell Ross, “Tomb 76: Catch”, from Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

5-RaMell Ross, “Here”, from South County, AL (A Hale County) (2012–14), from Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

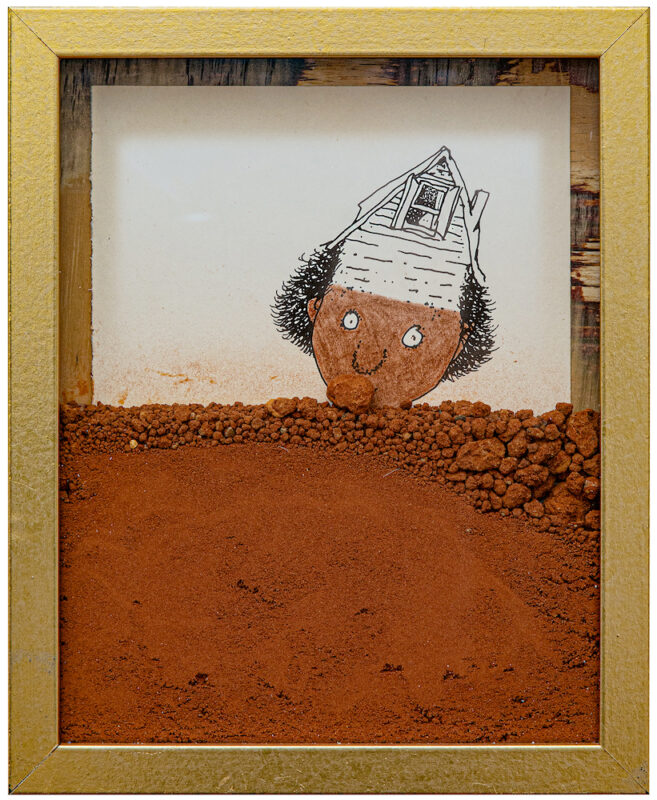

6-RaMell Ross, “Light in the Attic”, from Earth, Dirt, Soil, Land (2021), from Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

7-RaMell Ross, still from Return to Origin (2021), from Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

8-RaMell Ross, still from Return to Origin (2021), from Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

9-RaMell Ross, “Flag Case Black”, from Earth, Dirt, Soil, Land (2021), from Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

10-RaMell Ross, “Dakesha and Marquise”, from South County, AL (A Hale County) (2012–14), from Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.