Salvatore Vitale

How To Secure A Country

Essay by Max Houghton

Switzerland has long enjoyed its reputation as ‘the safest country in the world’, not least for anyone wishing to keep financial affairs private. Since the Treaty of Paris in 1815, self-imposed political neutrality has been central to Switzerland’s security. This decision saved thousands of Swiss – though few Jewish – lives during WWII, when the country was encircled by Axis powers. Neutrality, however, does not equal pacifism. With every male citizen aged 18-34 mandated to military service, Switzerland is a gun-nation, the third most heavily armed country in the world, after the United States, and Yemen, and where it is common-place to see a ten year-old loading SIG SG 550 or FAS 90 (similar to the AK47, but also customised for sport). In case of invasion, hyper-vigilant Switzerland is ready to defend its territory.

Making citizens feel safe comes at a price, of course, as Josef K. found out, to his detriment and eventual voluntary suicide, in Kafka’s The Trial. Kafka was matchless in describing what happens to a person, when everything and everyone is perceived in terms of a threat; a kind of disintegration at the level of the soul. Spiritual bankruptcy.

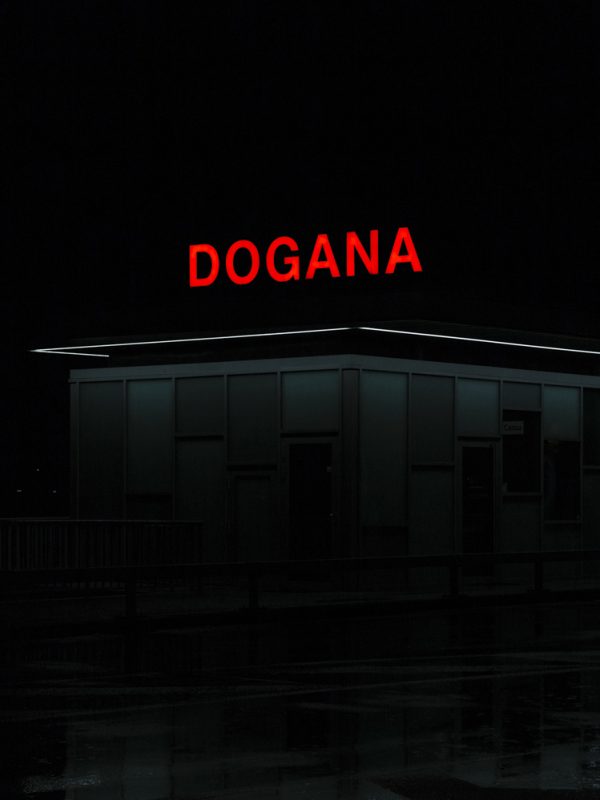

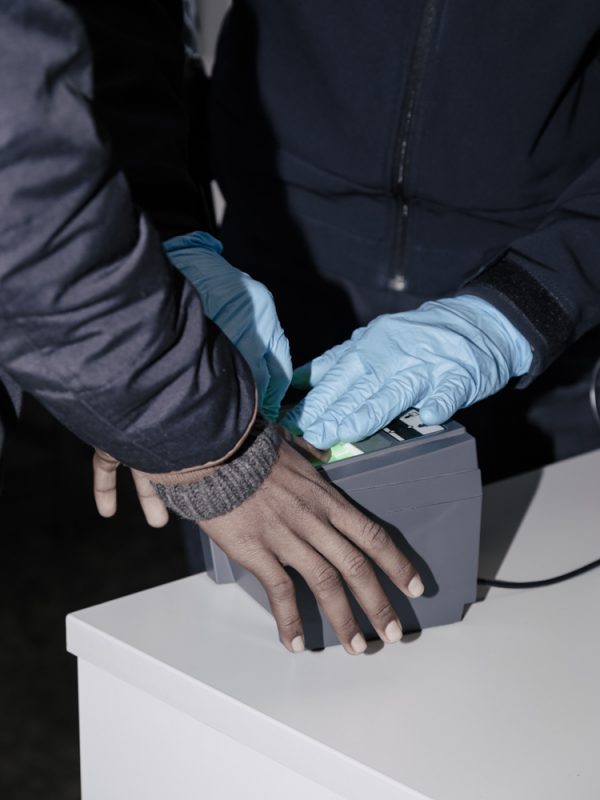

A question hovers, and remains ever-present: when does a threat become a risk? Looking for the answer has preoccupied photographer Salvatore Vitale, a Sicilian, who has been living in Switzerland for the past twelve years. One imagines the initial shock of experiencing the smoothness and visibility of a Swiss road at night. His adopted home, surrounded by mountains, enfolded into the very centre of Europe, offers unique social, political and financial protection to its citizens; it is palpable. Vitale could feel it in the air. Over time, his observations of differences in efficiency and state protocols inspired a desire to create an extensive visual research into How To Secure A Country. He began to collaborate with the prestigious ETH university in Zurich, a relationship which has proved essential in both trying to assess one of the most complex security systems in the world and in gaining permission to access places otherwise sequestered. The collaboration functions at many levels and is used by Vitale specifically to be responsive to interests outside the art world. By being guided by specialists within various institutions, he aims to show how the system works from the inside. This approach to research is as refreshing as it is rigorous.

Looking at Vitale’s meticulous, clinically clean Switzerland, we might begin to comprehend that the landscape we more stereotypically associate with skiing or yodeling or Heidi is in fact weaponised, to use a popular term, or we could say ‘securitised’. Mountains are hollowed out to house entire army divisions. Fake stonework conceals artillery; domestic residences in chocolate-box pretty villages harbor canons; bridges are stuffed with dynamite, ensuring all roads become dead-ends in the event of an attack.

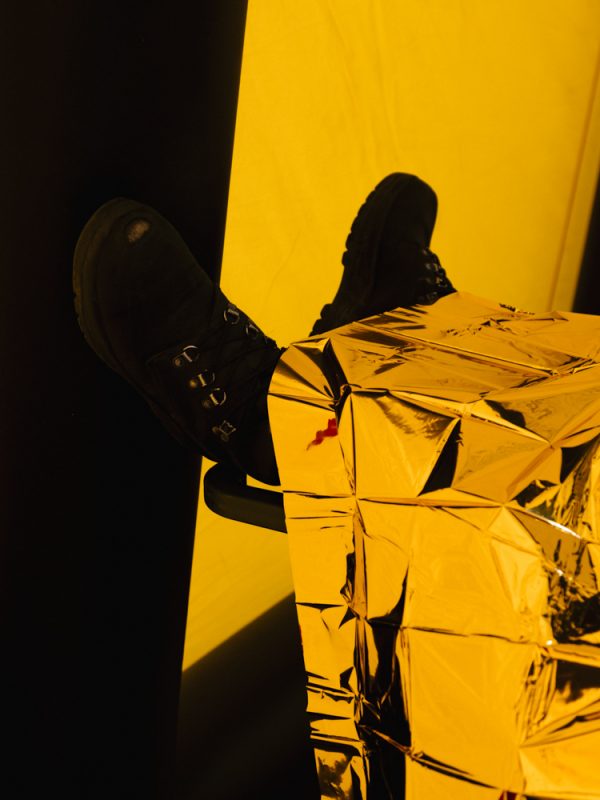

‘Pre-emption.’ Brian Massumi writes, ‘is the generative logic of our time.’ He is writing, in Ontopower, about post 9/11 USA, but the Swiss approach might operate as a kind of antecedent. The experience of looking at Vitale’s chilling imagery reminds us how ‘[t] his incipience of an event as yet to be determined, overfull with really felt potential, carries an untenable tension.’ Vitale has striven to find an aesthetic approach that bears witness to this tension. He has restaged the contents of instruction manuals, spent time in border control rooms, weather stations, and airport watch-towers, and been present at simulation exercises in order to understand the production of security. Vitale’s eye also takes in the environment in the shape of mountain valleys, nocturnal foliage, a lake inhabited by a police diver. To further the connection with Massumi’s thinking, Vitale’s enterprise reveals how state power is a significant factor in shaping the very environments in which we live. Eventually, it all becomes entirely natural.

Vitale is also spending time – the project is ongoing – at MeteoSwiss, which supplies vital meteorological analysis via its super computer in Lugano. There is a productive connection between the weather and state security, which Vitale is exposing, in terms of air traffic, both civil and military, or chemical or nuclear accident, for example, as well as providing forecasts for climbers or hikers, who would be at risk from extreme weather. In wealthy Switzerland, the profitable insurance industry relies on such risk analysis.

Piecing together the many links in this unwieldy network, via Vitale’s imagery, we begin to see how a politics of knowledge is created through power relations. He brings us a sonar image, used on a rescue mission undertaken by Swiss lake police, who provided the image. Sound wavelengths in water are approximately 2000 times longer than those of visible light, which makes it possible to ‘see’, when light can’t penetrate far enough. The resulting image can only be interpreted by a highly-trained expert, leaving the layperson to consider it purely as visual spectacle: a narrow, symmetrical chasm between two masses, with an unidentifiable circular ring to the top right. Scientists have employed sonar imaging techniques in Lake Neuchatel to find evidence of tectonically active zones that might trigger earthquakes, for example. Seek and you shall find.

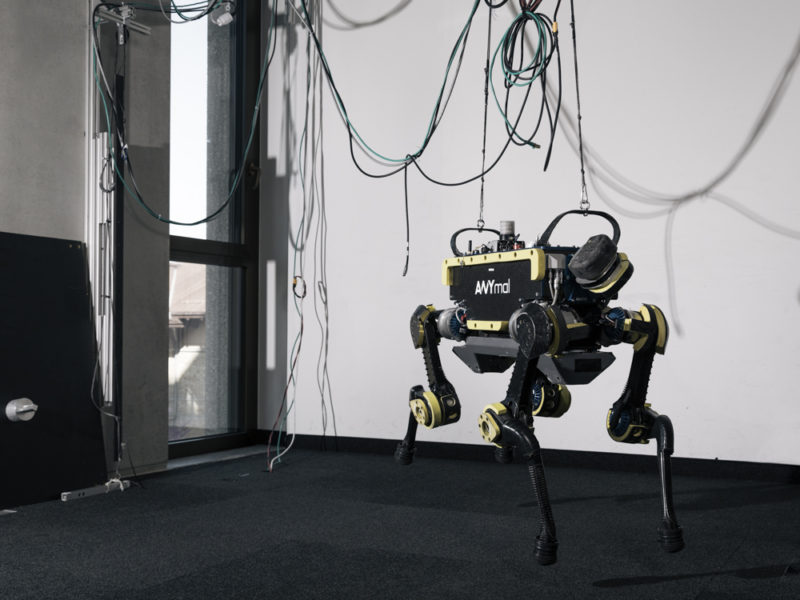

As might be expected, technology is at the forefront of security production. While older methods of detection are still utilised – as we see in the image of the sniffer dog – the most advanced robotics technology is playing its role too. Vitale introduces us to ANYmal, which (it is tempting to say ‘who’) is being developed for rescue missions, and is designed for autonomous operation in challenging environments. Robotics research has been focused predominantly in this area since Fukushima. The inclusion of ANYmal in this series seems ominous. The human body begins to feel superfluous.

Perhaps the most revealing glimpse into the production of security is the series of still images, the title of which translates as The six errors with regard to security threats. Classic stock imagery of elegant ballets dancers, or three generations of a healthy Swiss family, is juxtaposed with more sinister pictures – a hooded person at a keyboard, a raging fire. The original video is a Swiss Army production, at once bane and antidote: one the one hand, it educates the public on possible dangers to their culture or economy, while at the same time, presents the army as the necessary solution; guarantor of peace and prosperity.

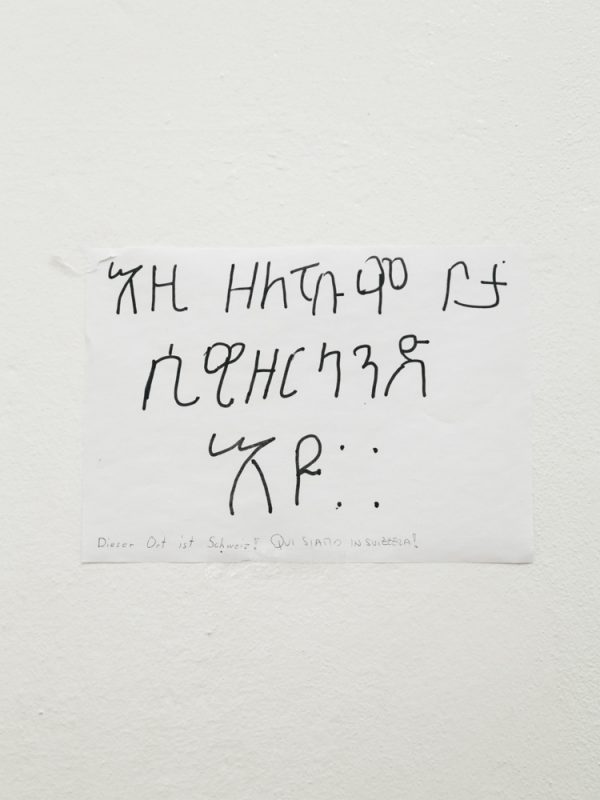

A couple of images offer brief respite from the tightly-calibrated visual regime. Vitale’s research began with border control, where, outside the inspection rooms and the extraterritorial space of the airport, he observed traces in the landscape, left by refugees. The viewer is affected by this fleeting human touch. A hand-written note in Tigrinya, the Eritrean language, offers reassurance for those that might follow in their footsteps: ‘We are here. You are in Switzerland.’ Elsewhere, a vivid red map acts as a warning to fellow refugees, to make clear that Switzerland is in fact a country in its own right.

A final image in this illuminating series shows a white cross on a red square, one of the most-recognised flags in the world, or the looking-glass version of a never-ending state of emergency. The disaster-to-come is always already present. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Salvatore Vitale

—

Max Houghton writes about photographs for the international arts press, including FOAM, Photoworks and The Telegraph. She edited the photography biannual 8 Magazine for six years and is also Senior Lecturer in Photography at London College of Communication – University of the Arts, London.