Cao Fei

Blueprints

Essay by Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo

Following Cao Fei’s recent Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize ‘win’, Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo investigates the artist’s incorporation of science-fiction narratives and exploration of technology’s role in shaping our collective futures against the backdrop of China’s ongoing conquest of space.

“We have a winner!” the Deutsche Börse website published after Cao Fei was awarded the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2021, staged at The Photographers’ Gallery, London. For art world specialists, the reading is easy, perhaps too easy. But for the rest, a few questions quickly arise: who is Cao Fei; what is the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize; and who wins?

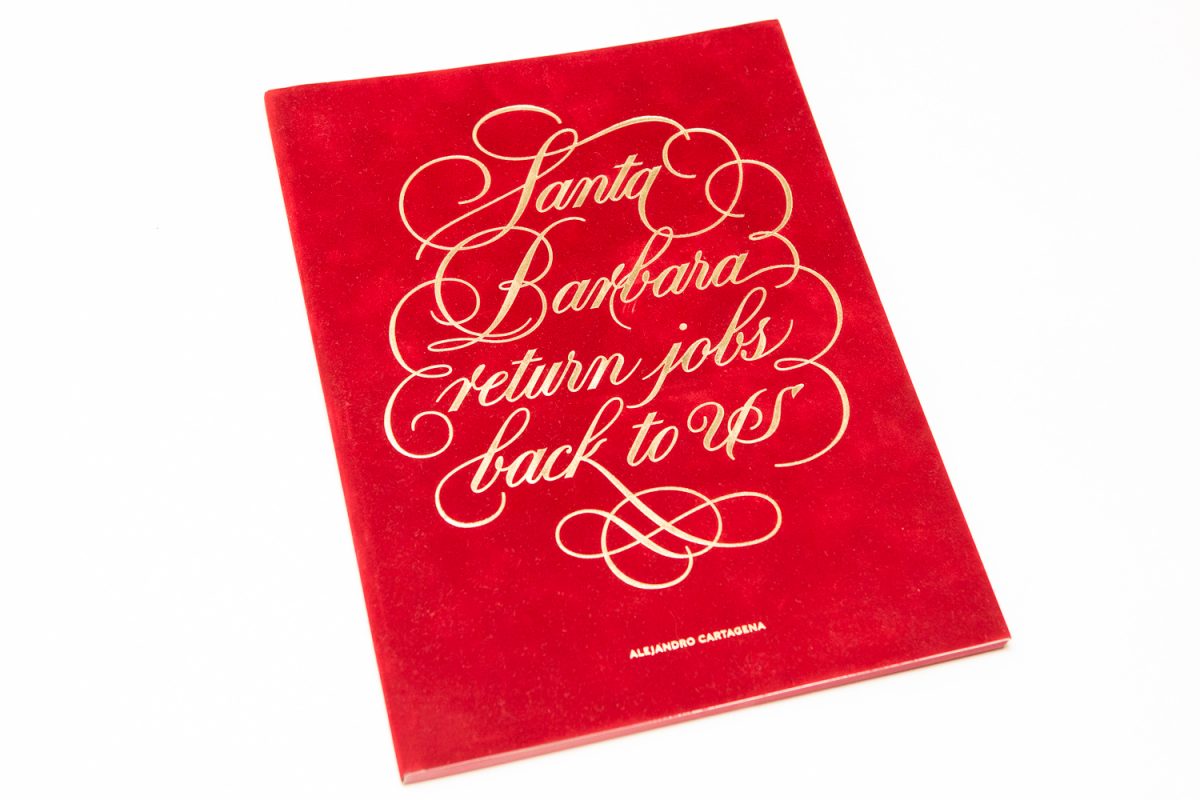

Cao Fei is probably one of the most innovative Chinese artists to emerge on the international scene. Her career has been meteoric. In 2000, Fei was still a student at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts when she was ‘discovered’ by curator Hou Hanru, who introduced her to the art world. Since then, Cao Fei, who is best known for her multimedia and video productions, has presented work at the Venice Biennale, Centre Pompidou, Paris, and Guggenheim Museum, New York, amongst many others. It was for her first large-scale solo exhibition in the UK, Blueprints (2020) at the Serpentine Gallery, London (supported by LUMA Foundation and Muse, the Rolls-Royce Art programme), that she was awarded the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2021. The other nominees were Poulomi Basu, Alejandro Cartagena and Zineb Sedira.

The Deutsche Börse is of course an international exchange organisation and innovative market infrastructure provider, offering customers a wide range of products, services and technologies across the entire value chain of financial markets. Perhaps one of the broadest questions when thinking about the current global political context is: why did a Chinese artist win an award from a German exchange organisation at an English gallery for the exploration of photography?

In attempting to answer this question posed by the price of photography, one could start with the exhibition’s title. A blueprint is a reproduction of a technical or engineering drawing through a process of contact printing on light-sensitive sheets. It was introduced by the English scientist Sir John Herschel in 1842, and used widely for over a century. One might, in turn, ask: what is Cao Fei’s engineering project? Her presentation at the Serpentine Gallery came shortly after her latest commission was exhibited on the rooftop of the National Gallery of Singapore: a large-scale, kinetic sculptural installation entitled 浮槎 Fú Chá, alluding to a mythical Chinese raft that not only sails across the ocean, but also floats up towards Tianhe (both a translation of “Milky Way” as well as the name of the new Chinese space station, which recently launched its first module). At the top of Cao Fei’s rooftop structure flashed a neon message: “Almost Arriving”.

It is also helpful to go back in time. In October 1957, against the backdrop of the Cold War, the Russian satellite Sputnik triggered the Space Race. The launch ushered in a new era of political, military, technological and scientific advances. Today, half a century later, in the context of planetary crises which threaten our collective future – from climate and biodiversity to pollution and waste – many humans are re-thinking alternative ways of living, whilst others of continuing the conquest of space. In 2020, the 3D-printed building company ICON won a contract from NASA to develop a robotic, extraterrestrial construction system for the Moon. Furthermore, a well-known South African entrepreneur and business tycoon has founded an aerospace manufacturer and space transportation services company, SpaceX, that uses engines powered by cryogenic liquid methane and liquid oxygen. An American rover on Mars not only looks for signs of habitable conditions in the planet’s ancient past, but also for signs of microbial life in the present.

Following centuries of isolation, the Asian giant has undergone, in just a few decades, some of its most significant transformations in its very long history, particularly across coastal and industrial areas. However, China seems reluctant to choose between the innovations of the West and the traditional immobilities of the East, yet is determined to undertake the modernisation of its economy. Cao Fei’s characters navigate these chaotic realities with vigour and agency by harnessing the unique possibilities of technology. It is impossible not to think of Ursula K. Le Guin’s utopian science-fiction novel The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia (1974), Steven Spielberg’s film Real Player One (2018) or the young entrepreneur who bought a digital artwork for $69.3 million at Christie’s on 11 March 2021: the same person who owns millions of hectares of virtual land, who might soon begin building his foundation thanks to Frank Gehry; perhaps in a few months his new digital art archipelago will be ready to show his NFT collection.

Cao Fei’s research has a complex, open structure that corresponds to the irreducible depth of the themes she explores. Her conceptual approaches consist of making evident the fact that the subjects of representations of labour are not absent from art production. More specifically, her films suggest that the visual strategies of ironic simulation might not have come to an end as Benjamin Buchloh stated when The Forgotten Space (2010), one of the most important film essays by Noel Burch and Allan Sekula, came out. Cao Fei’s work presumes that simulacrum will serve the purpose of conveying workers’ aesthetic, social and political experiences. Whilst actual labour conditions are no mystery, Chinese workers pay a particularly heavy human price in enabling our civilisation to “go-green”, especially in the Heilongjiang province, where such activity occurs in an atmosphere saturated by hydrofluoric acid. China is the leader in the production and trading of rare substances crucial in the production of “clean” energy, electric vehicles and consumer electronics; the very same used by us every day and by Cao Fei in unveiling her narratives about development, love and technology.

The work of Cao Fei thus possesses a strong common thread: the denunciation of the communist utopias of the past, as well as China’s capitalist rise in the last twenty years. In charting the transitions that Chinese society is undergoing and benefiting from, is she merely criticising a culture ruled by video games and hyper-consumerism?

With policymakers recognising science-fiction as a potentially powerful tool for promoting state-sanctioned ideology, government agencies have encouraged Chinese filmmakers to incorporate such narratives which align with the regime’s broader ideological and technological ambitions. In other words, China uses mythology and science-fiction to sell itself to the world, as we can see today through its space programme. Cao Fei asks questions about technology’s shaping of a collective future, but who is part of this collective? The fantastical aspects of Fei’s work might explain why the science-fiction genre is being promoted internationally first and foremost over other commercial products that present images of China’s communist-capitalist regime. Unlike China’s expanding capabilities in space, which are seen by the world as a threat, the country’s fictional extraterrestrial developments pose no real-life risk. But none of this seems like science-fiction any more. It is impossible to forget that in January 2021, the UK’s Brexit transition period ended, culminating in exiting the EU after years of negotiations between London and Brussels. The effects of the country’s divorce from the Union have been felt everywhere, in economic, socio-political and scientific terms. Under the Brexit arrangements, the UK no longer participates in European satellite navigation systems, such as Galileo or EGNOS.

Over time, Cao Fei’s UK audience might become more comfortable with the notion of China as a global technological leader offering its customers a wide range of products, services and technologies. And this, in turn, might cultivate an interest either in the blueprints of the mythical Chinese devices floating through the Milky Way, or an awareness of the significance of memory and the ways in which the past can come to haunt the present: images are, in effect, the opium of the West.

I have one last question: who is the winner? ♦

All images courtesy artist, Vitamin Creative Space and Sprüth Magers © Cao Fei

Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2021 at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, ran from 25 June – 26 September 2021.

—

Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo is an artist and curator, currently completing his PhD at the École nationale supérieure de la photographie (ENSP), Arles. After one year at the National School of the Arts (NSA), Johannesburg, he graduated in Photography in Chile and completed his Masters of Fine Arts at the Villa Arson, Nice, in 2014. He has curated exhibitions including Mapuche at the Musée de l’Homme, Paris, and Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation at the Rencontres d’Arles, which has been on tour for four years under his permanent supervision. Valenzuela Escobedo is a guest tutor at international art schools and institutions, most recently at the Institut d’études supérieures des arts and Parsons, Paris, International Summer School of Photography, Latvia, and Atelier NOUA, Bodø. He is co-founder of Double Dummy studio, a platform that creates a space for producing and showcasing critical reflections on documentary photography.

Images:

1>4-Cao Fei, Nova, 2019.

5>7-Cao Fei, Asia One, 2018.

8-Cao Fei, Whose Utopia, 2006.

9-Cao Fei, Cosplayers, 2004.