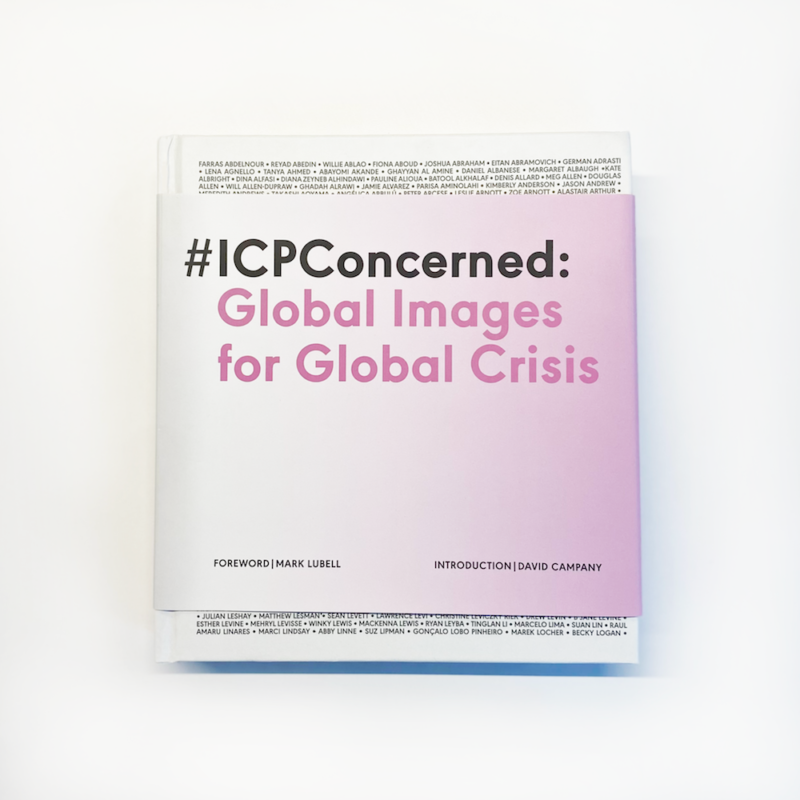

Photo London 2022

Top five fair highlights

Selected by Alessandro Merola

Bringing together over 100 exhibitors from around the globe, Photo London has returned to Somerset House for its seventh edition. Brimming with bold impressions on the medium from early trailblazers through to today’s most exceptional talents, it has something for all tastes. Here are five standout displays from the capital’s premier photography fair – selected by 1000 Words Assistant Editor, Alex Merola.

1. Once Upon the War in Kharkiv

Alexandra de Viveiros

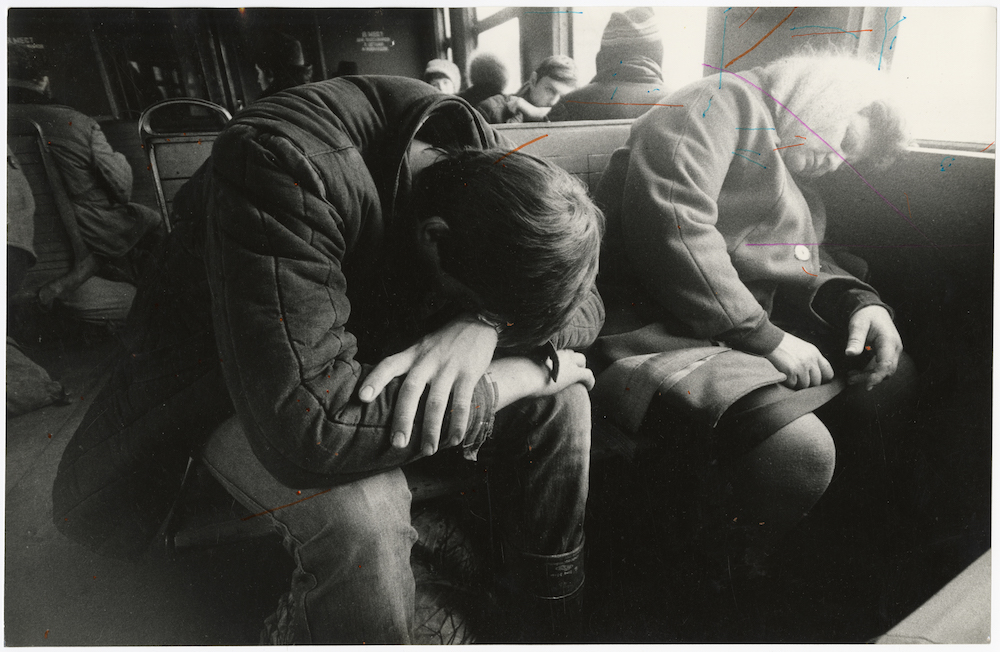

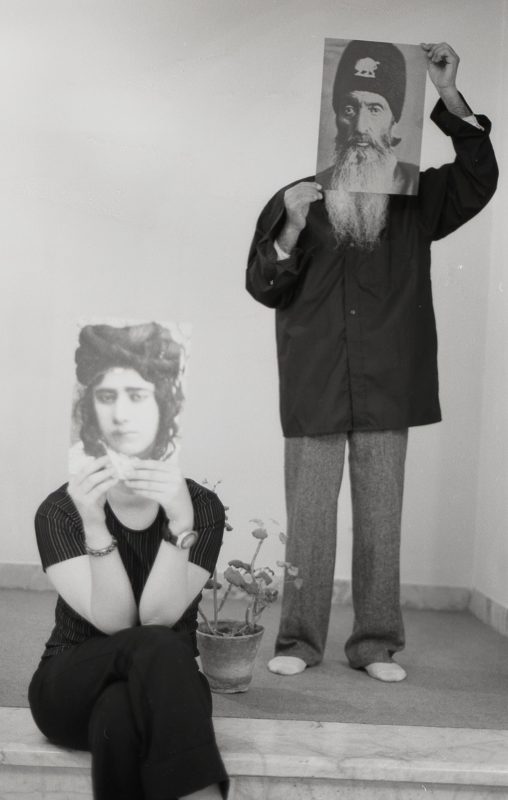

Maintaining a robust commitment to the dissident photographers of Ukraine’s Kharkiv School of Photography – borne in the early 1970s out of a city now besieged by Russian troops – Alexandra de Viveiros’ presentation prompts a particularly urgent viewing. Of marked significance here are the pieces by Evgeniy Pavlov, one of the co-founders of the Vremia Group, which set out to create a visual opposition to dominant Soviet narratives and the aesthetic canon of Social Realism. Pavlov’s Archive Series (1965–88) italicises scenes of everyday life with a quiet, personal lyricism through colour retouching, whilst his ragged photo-collage, dated 1985, keeps the mind busy and ambiguity open. Sharing these walls with Pavlov are father and son Victor and Sergey Kochetov, whose wonderfully expressive hand-tinted prints – referencing Boris Mikhailov’s art of luriki – communicate both the backwardness of Soviet technology as well as a nostalgic attachment towards it. With the inclusion of the School’s newest wave of activities – Vladyslav Krasnoshchok’s harrowing hallucinations of the medical emergencies at a Kharkiv hospital, for instance – de Viveiros has staged a small but powerful constellation bringing together three generations of Ukrainian photographers, all united in their upholding of the right to independence and the freedom of artistic gesture.

2. Anastasia Samoylova, Floridas

Galerie—Peter—Sillem

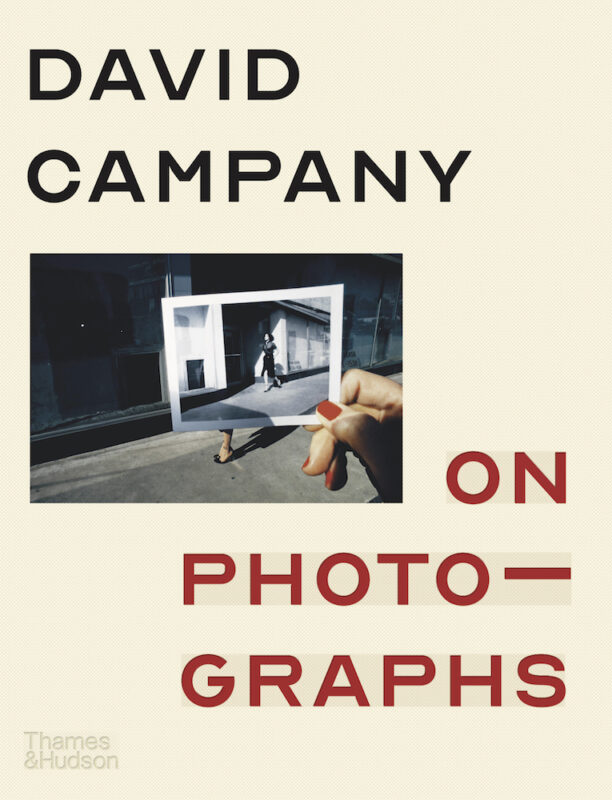

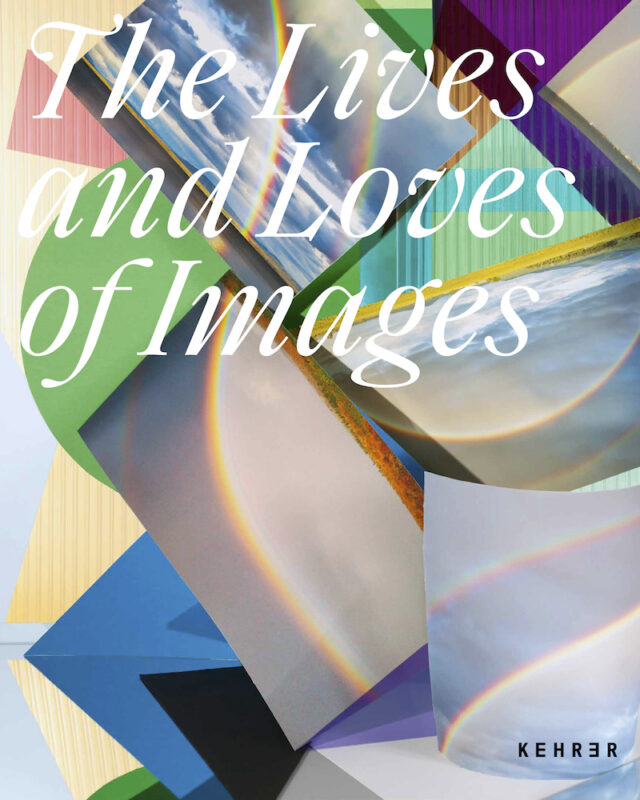

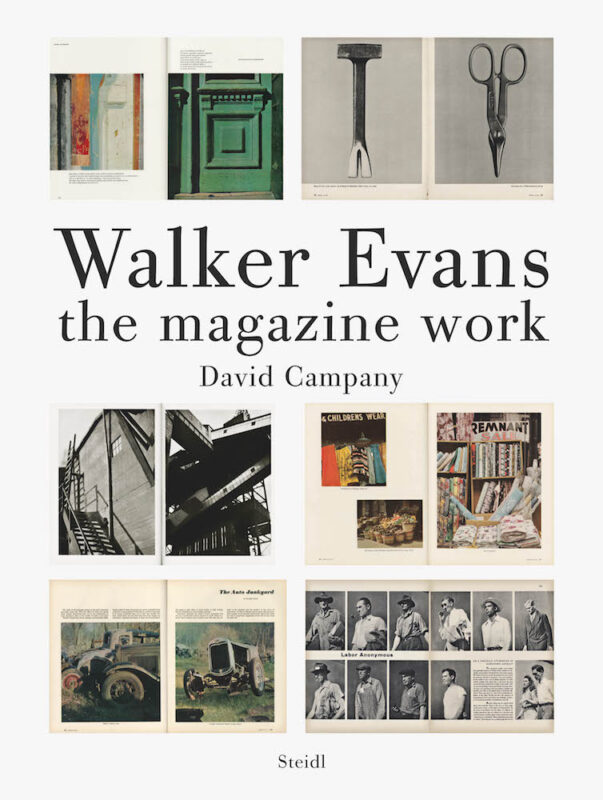

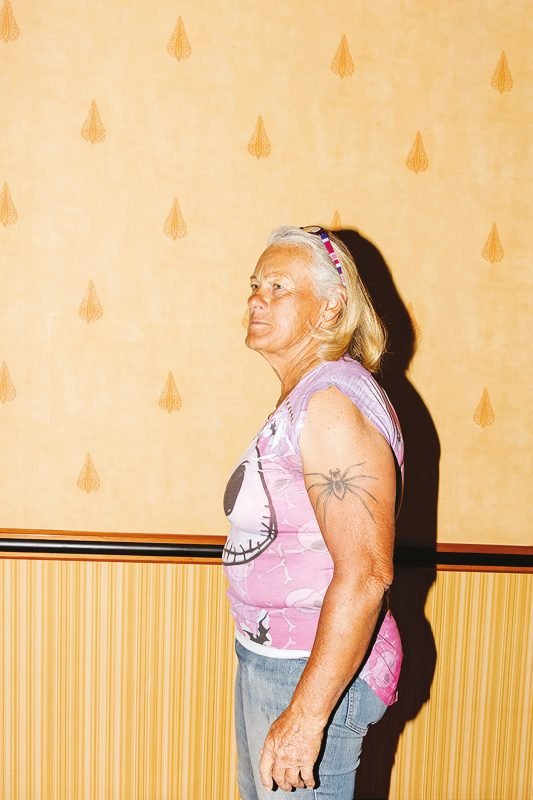

Concurrent with showing at The Photographers’ Gallery as part of the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2022, Anastasia Samoylova’s solo booth with Frankfurt’s Galerie—Peter—Sillem is an unmissable affair. Hung in handsome, white-wooden frames, the artist’s prints prevail for their technical brio: sleek, delectable renderings of colour which magically transcribe that distinctly brilliant Floridian light. However, what’s alluring is also alarming, for they convey the contradictory lives of a state totally distracted by its own self-image whilst in the throes of ecological implosion. Though these layered photographs contain subtle references to Walker Evans’ extensive but oft-overlooked body of work made in “Sunshine State” – a kinship teased out in Floridas (2022), her exceptional new book which is available to peruse here – Samoyolova is very much her own artist. Her merging of meticulous observation, deceptive aesthetic and sharp socio-environmental concern marks her out as one of the most intelligent and sophisticated photographers working today – and, indeed, one of the most important to reckon with the fallacies of Florida.

3. Christine Elfman, All solid shapes dissolve in light

EUQINOM Gallery

With an eye for experimental and rigorous photo-based practice, San Francisco-based EUQINOM Gallery has delivered a dynamic display as part of this year’s Discovery section – dedicated to emerging galleries and overseen by 1000 Words Editor-in-Chief, Tim Clark. Commanding a particularly slow and conscious appreciation here are the variously violet-hued anthotypes of Christine Elfman, who, with her series All solid shapes dissolve in light (2019–22), has developed an exquisite technique involving light-sensitive dyes harvested from lichen and month-long solar exposures to produce photographs whose chemical properties mean they are constantly fading. Boasting breathtaking degrees of detail, these capricious pieces reveal those infinitesimal shifts in colour, contrast or density to only the most patient and attentive observers. That these studies are at once disappearing and also becoming is perhaps their most confounding and, ultimately, magical quality. Elfman is evidently as curious about philosophical questions as by photographic ones, and how thrilling it is to find an artist employing such an early analogue process whilst, in turn, upending that dusty, medium-old fantasy of ‘fixity’.

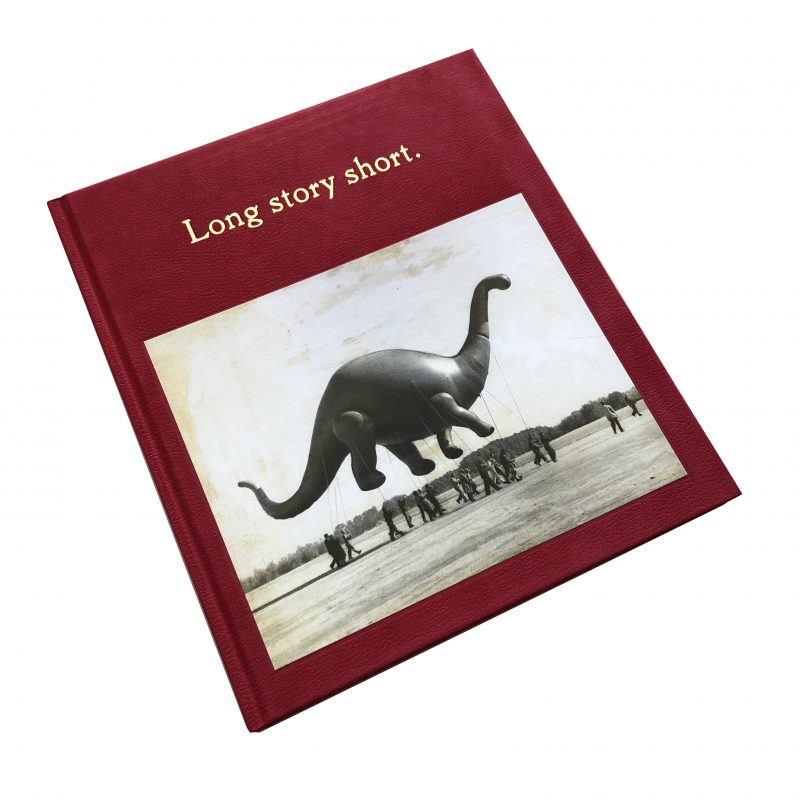

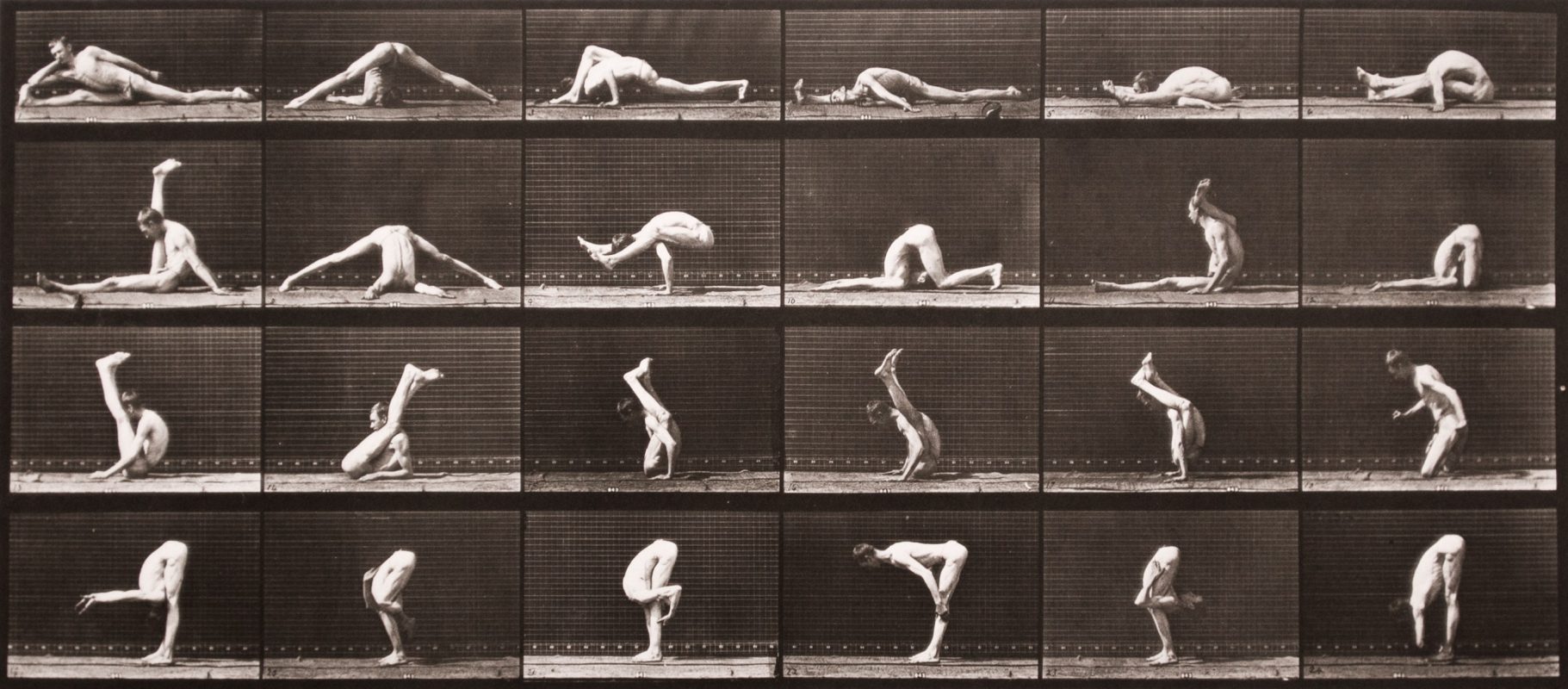

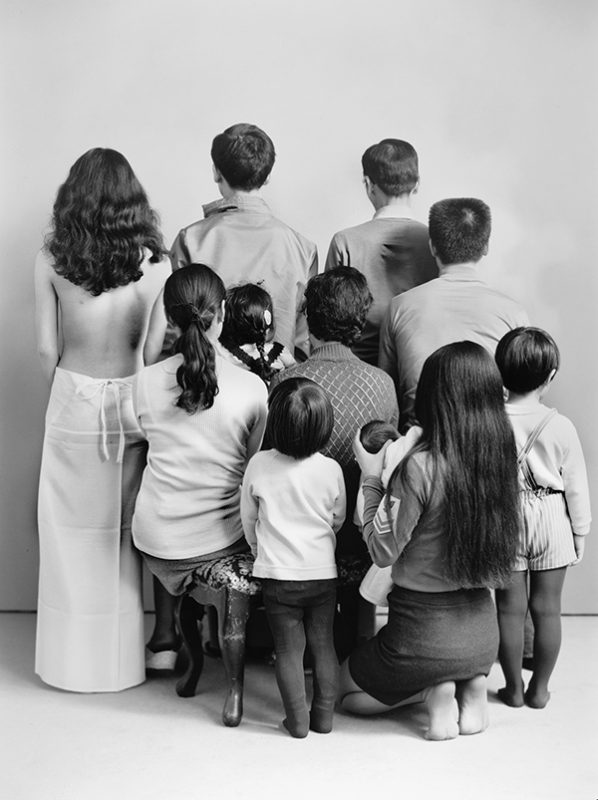

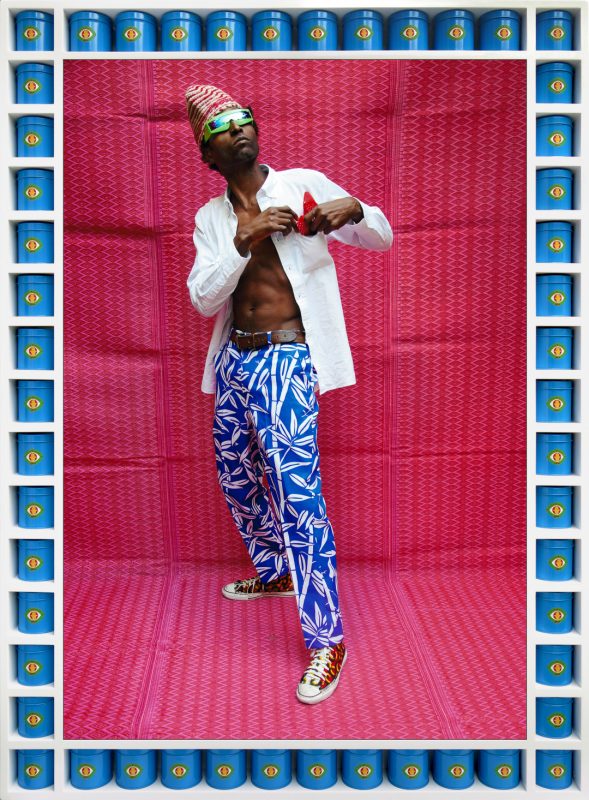

Few in the UK have done more to further the integration and celebration of so-called “outsider artists” – historically sideswiped by the mainstream – than James Brett has, and the fine line he has drawn between the professional and the vernacular at The Gallery of Everything’s (debut) outing makes it one of the most stimulating of this year’s fair. There’s a charming amateurism in the air, with some of the superstars of self-taught image-making packing these walls. Miroslav Tichý’s small, weathered objects – stolen glimpses of female forms through cameras constructed from cans and junk – wind up with a melancholic resonance, as do the mise-en-scène of Morton Bartlett, a fascinating figure who, in the 1940s and ’50s, built and photographed a cast of life-sized dolls that sublimated his lack of “real” relatives (there’s a unique opportunity to see one in the flesh, too). In the company of William Mortensen’s beguiling studio shot of a witch flying a broom, Bartlett’s works surprise for their uncanny awareness of the power of light, shadow and composition. Turning it up a notch are Pierre Molinier’s silver gelatin prints: formally-classic yet thoroughly transgressive propositions on gender, fetishism and narcissism. Flailing an impossible number of limbs encased in stockings, he’s seen through a peep hole, like this booth in general.

5. The Countess of Castiglione

James Hyman Gallery

For their rarity alone, the private, performative self-portraits of the Countess of Castiglione are a must-see. Yet, what is most successful about James Hyman Gallery’s tightly-curated booth, comprised of over 50 prints from three periods (1856–57, 1861–67 and 1893–95), is the way in which it offers a complex narrative arc charting the seductress’ mutating identities and inner-realities. However compliant in the eye of the camera the Countess might appear – self-masqueraded with masks, ballgowns and crowns which, as Abigail Solomon-Godeau argued, saw her act as a ‘scribe’ of predetermined and delimited feminine tropes – she is a rare example of a 19th century woman constructing images for her own gaze: a subject tricking us into thinking she is an object. Whilst the cynosure here is a pair of gold-framed, elaborately-painted photographs which have been unveiled for the first time ever, the most poignant pictures are the final ones through which the aristocrat confronts the impermanence of her beauty. This is a very special tribute to a practitioner whose place within the canon, one feels, should be radically reconsidered. After all, before Cindy Sherman and indeed Claude Cahun, there was the Countess, delving into the work images do and the lives they somehow lead us, or free us, to live.♦

Photo London runs at Somerset House until 15 May 2022.

—

Alessandro Merola is Assistant Editor at 1000 Words.

Images:

1-Evgeniy Pavlov, ‘Untitled’ from Archive Series (1965–88). Courtesy the artist and Alexandra de Viveiros.

2-Viktor and Sergiy Kochetov, ‘Untitled’ (1990). Courtesy the artist and Alexandra de Viveiros.

3-Vladyslav Krasnoshchok, ‘Untitled’ from Bolnichka (2010–18). Courtesy the artist and Alexandra de Viveiros.

4-Anastasia Samoylova, Venus Mirror (2020). Courtesy the artist and Galerie—Peter—Sillem.

5-Anastasia Samoylova, Rust, Hollywood (2019). Courtesy the artist and Galerie—Peter—Sillem.

6-Anastasia Samoylova, Chain Link Fence, Miami (2018). Courtesy the artist and Galerie—Peter—Sillem.

7-Christine Elfman, Cloth Water Stone II (2021) (Variation II). Courtesy the artist and EUQINOM Gallery.

8-Christine Elfman, Reproduction I (2020) (Variation II). Courtesy the artist and EUQINOM Gallery.

9-Christine Elfman, Reproduction III (2021) (Variation III). Courtesy the artist and EUQINOM Gallery.

10-Miroslav Tichý, ‘Untitled’. Courtesy The Gallery of Everything.

11-Morton Bartlett, ‘Untitled’ (c.1950). Courtesy The Gallery of Everything.

12-William Mortensen, Myrdith on Broom (c.1930). Courtesy The Gallery of Everything.

13-Pierre Molinier, ‘Untitled’ (1966). Courtesy The Gallery of Everything.

14-The Countess of Castiglione in collaboration with Pierre-Louis Pierson, L’innocence, variation sur La Reine D’Etrurie (1863). Courtesy James Hyman Gallery.

15-The Countess of Castiglione in collaboration with Pierre-Louis Pierson, La toilette (1861–67). Courtesy James Hyman Gallery.

16-The Countess of Castiglione in collaboration with Pierre-Louis Pierson, La Comtesse de Castiglione (1894). Courtesy James Hyman Gallery.