Andreas Gursky

Visual Spaces of Today

Essay by Urs Stahel

Andreas Gursky. Visual Spaces of Today at Fondazione MAST, Bologna, marks the first extensive anthology in Italy covering four decades of the artist’s oeuvre. Known for his large-scale photography, Gursky’s iconic representations of the contemporary world have contributed to elevating the status of photography to an art form, turning it into a collector’s item for museum and private collections internationally. Here, exhibition curator Urs Stahel outlines the continued importance of his work arguing that its enormous visual power is such that entering into the universe of his images becomes each time an experience and a step towards awareness – the opposite of the new world of miniature, ultrafast images we consume daily through smartphone technologies and social media.

Andreas Gursky is a photographer, a successful artist using the medium of photography, who lives and works in Düsseldorf. He is 68 years old. “Andreas Gursky,” on the other hand, signifies far more than that, embodying an art form, international fame; a brand that, since the late 1980s and early 1990s, has stood for “large-scale photography,” for “photography and art,” for record auction prices, and, with that, for a whole new era of photography: photography in art museums, photography in art collections. At long last, following an ongoing struggle throughout the lifetime of photography. Elsewhere, I once wrote euphorically: “Waving flags, our rallying cry is: Yes, photography is art! Yes, photography has a place in art museums and art collections! Yes, photography can be an autonomous image and not just a mechanical-electronic record of reality. At last! The goal has finally been reached.”[i]

This new status was most clearly evident in the development of the market – a market for photography that began to emerge in the 1970s, gradually at first, and step by step. Until then, the photographic print had been regarded primarily as a printing template and if one or more prints of the same photo were made, then that tended to be a matter of personal choice or was based on the popularity of the subject matter, rather than any marketing considerations. In the early 1980s, however, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico – one of the most famous photographs by Ansel Adams – fetched the previously unmatched record price of $71,500 at auction.[ii] In the 1990s, it was historical works that tended to dominate, such as Gustave le Grey’s cloud study La Grande Vague, which was auctioned in 1999 for around 900,000 Euro (the equivalent of 5.5 million French Francs at the time). After the turn of the millennium, works by Andreas Gursky began to achieve record prices, initially for multiple prints of his 99 Cent and 99 Cent II, and culminating in a record-breaking 4.3 million dollars for his work Rhein II in 2011, which remained unsurpassed for the next eleven years.[iii]

These record prices provided ample media fodder, yet at the same time they were a clear indication of how strongly photography had evolved and established itself as a medium and collector’s item in its own right since the 1970s, and how intensely the image itself, both in painting and photography, had made its comeback within the context of the art world. This resurgence, which seemed like a new beginning, was so unexpected, so overwhelming, and such a pivotal moment for photography, that it is worth taking a closer look here at how it all began.

The 1960s and 1970s are regarded as iconoclastic decades in Western art, which saw an adamant rejection of the panel painting and a departure from the classical notion of the image, as well as an emancipatory release from the immobile, fixed, framed object in favour of the mobile and the thought-provoking, such as Happenings and Performance Art, and the conceptual, including Land Art. These two decades also represent a critical view of the museum as institution and a questioning of the attendant bourgeois institutional codes that evaluate and sanction art. So the dual return of artists and their pictures to the museum seemed astounding. Following the “linguistic turn” of the 1960s, the linguification of art and the advance of structuralism in the discourse, art theory was full of talk about the “image turn,” the “pictorial turn” and the “iconic turn.” And many, in their astonishment, began to ask, as Louise Lawler did so elegantly and succinctly: “Why pictures now?”[iv] Why had they come back, and why with such force, and what did these images of the 1980s actually do and mean?

In his 1983 text Why I Go to the Movies Alone, Richard Prince imbued this question with substance and desire:

“The first time he saw her, he saw her in a photograph. He had seen her before, at her job, but there, she didn’t come across or measure up anywhere near as well as she did in her picture. Behind her desk she was too real to look at, and what she did in daily life could never guarantee the effect of what usually came to be received from an objective resemblance. He had to have her on paper, a material with a flat and seamless surface, a physical location which could represent her resemblance all in one place, a place that had the chances of looking real, but a place that didn’t have any specific chances of being real.

His fantasies, and right now, the one of her, needed satisfaction. And satisfaction, at least in part, seemed to come about by injesting, perhaps ‘perceiving,’ the fiction her photograph imagined.

She had to be condensed and inscribed in a way that his expectations of what he wanted her to be (and what he wanted to be too) could at least be possibly, even remotely, realised. Overdetermination was part of his plan and in a strange way, the same kind of psychological after-life was what he loved, sometimes double loved about her picture.

It wasn’t that he wanted to worship her. And it wasn’t that he wanted to be taxed and organised by a kind of uncritical devotion. But her image did seem to have a concrete and actual form, an incarnate power, a power that he could willingly and easily contribute to. And what he seemed to be able to do, either in front or away from it, was pass time in a particular bodily state, an alternating balance which turned him in and out and made him see something about a life after death.”[v]

In this prose poem, Richard Prince generates and at the same time describes the desire of the image: preferring the image to the reality is ultimately a desire that also finds fulfilment in the experience of a life after death. Here, Prince provides us with his velvet reason (“The Velvet Well,” as he called it) for the return of the image to the museum in the 1980s: as part of a gradual shift from a fascination with reality to a fascination with the image of reality. Just as we speak today of digital natives, we might describe this as the realm of the first medial natives, in that they were the first generation to grow up in a world of mass media, television and advertising, saturated with images and dominated by what enlightened critics at the time described as the “consciousness industry.” This generation has come to be known, borrowing the title of the 2009 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, as the “Pictures Generation.”

In his book Photography Until Now, John Szarkowski describes this development, as it relates to photography, in the following terms: “The addition of photography to the liberal arts curriculum was a phenomenon particularly marked in the United States: in the three years between 1964 and 1967 the number of colleges and universities that offered at least one course in photography increased from 268 to 440. In Europe, in schools such as Hans Finsler’s Kunstgewerbeschule in Zurich and Otto Steinert’s Folkwangschule in Essen, pedagogical styles continued to emphasise a relatively rigorous concentration on conventional craft virtues, and students of photography were more likely to be educated with future commercial artists and graphic arts specialists than with painters and traditional printmakers.”[vi] In the USA, by contrast, art education was far more strongly influenced by the ideas of Lászlo Moholy-Nagy. A remarkable number of the photography lecturers and tutors tasked with developing new art school curricula were themselves former students of the New Bauhaus, the Chicago Institute of Design, founded by Moholy-Nagy and headed by him until his death. Arguably the most impressive example was the founding of CalArts, the California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles, which was set up in 1970/71 with funding from Walt Disney. Paul Brach, the first director of CalArts, immediately appointed the young John Baldessari as professor. Baldessari threw all established guidelines overboard, according to the maxim: “You can’t teach art, that’s my premise […] We just eliminated grades. We had pass/fail. You can’t use grades as a punishment.”[vii]

Then (as now) it was the media theory of French philosopher and sociologist Jean Baudrillard that provided the theoretical basis, echoing this mindset and this understanding of the world and the media. Known in the 1980s and 1990s as a distanced diagnostician of modern mass media society, his key theory of simulation describes the social conditions of the twentieth century as shaped by the media. He sees society in the age of “simulation modernity” as being completely influenced by and dependent on media: “Everywhere socialisation is measured by the exposure to media messages. Whoever is underexposed to media is desocialised or virtually asocial.”[viii] In Die Agonie des Realen (1978) his point of view culminates in the observation that social occurrences are now initiated solely by the media, and also mirrored by the media. The result is a media-generated hyperreality in which it becomes impossible to distinguish between the authentic and the simulated, to the extent that the lack of reference in media signs makes any such attribution completely pointless.[ix] The indistinguishability between (historical) fact and (media) simulation ultimately results in the complete loss of access to any specifically perceptible reality. As Michael Wetzel puts it with regard to Baudrillard: “The world becomes the reason for its photographic and filmic reproduction and images from around the world replace our image of the world, our world view. It could be said that being-an-image gains ontological precedence over being.”[x]

Andreas Gursky positioned his first large-scale pictures within this radicalised context, this new field of art and the world. Although his path to becoming an artist had not been in the USA, following Moholy-Nagy in Chicago or with Baldessari at CalArts, he had studied at the Folkwang Schule in Essen under Otto Steinert, or was at least influenced by the ideas of Steinert (who died shortly after Gursky enrolled) and at the Düsseldorfer Akademie in the department known as the Becher Schule, under Bernd and Hilla Becher, graduating alongside Thomas Ruff and Axel Hütte, shortly after Thomas Struth and Candida Höfer. Steinert and his cohorts in the Fotoform group, with their idiosyncratic combination of abstract form and material under the lens of “subjectivity;” Bernd and Hilla Becher with their “neue Sachlichkeit” approach to industrial buildings and forms heralding a new anthropology of utilitarian structures that granted each building its own firmly anchored existence in spite of the typological similarities. Gursky, however, went beyond these source parameters, taking a more international view and often citing Jeff Wall as a key inspirational figure. The large-scale lightboxes of the Vancouver-based photographer brought billboard-sized street scenes, often featuring realistic reenactments of distinctly downbeat urban life, into the museum as works of art.

The European exhibition most closely related to Andreas Gursky’s start was Blow Up, which opened in 1987 at the Württembergischer Kunstverein in Stuttgart –appropriately, the very same year Gursky completed his studies in Düsseldorf – and went on tour under the guiding principle that “the artworks in the exhibition Blow Up – Zeitgeschichte document the intellectual independence of the artist in an era shaped by mass media and consciousness industries, and have a seismographic effect on art and society, as a reflection of our era.”[xi] The organisers and curators – Tilman Osterwold, Klaus Honnef, Peter Weiermair, Jean Fisher – had made a carefully calibrated choice of artists they felt best represented the emerging medium of large-scale photography. These included Joseph Kosuth, John Hilliard, Marina Abramovic und Ulay, Cindy Sherman, Clegg & Guttmann, Jeff Wall, Ian Wallace, Raimund Kummer, Christian Boltanski, Günther F.rg, Astrid Klein, Katharina Sieverding, John Baldessari, and Barbara Kruger. “The criteria for this are the distinctiveness of the large-format photograph, whose sheer scale has a presence that underpins the message of the image; the artist uses this medium in a targeted way as a central and crucial element of his work […]”. Or, in Klaus Honnef’s quintessential summary: “Artists who currently use photographic techniques and means to formulate their ideas find themselves confronted with the situation that the boundaries between empirical reality and the fictitious reality of the media have become blurred.”[xii]

The large format that Andreas Gursky was soon to choose is in itself a statement of the artist’s architectural, visual and content-related assertions, and one that challenges the viewer. In contrast to exhibitions of classic photographic formats such as 30 x 40 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 50 x 60 cm, through which we stroll and pause to look at each image for a time, feeling bigger and more powerful than the images themselves, with a sense of superiority, and an awareness that the exhibition space remains more or less unchanged, these largescale works transform the space and redefine it, confronting us as viewers either subtly or forcefully, opening our eyes or dominating our gaze. They pose a physical challenge and, at the same time, invite us to come closer and engage with them visually, immersing ourselves in them. From the very beginning of his career, since his first large-format works, Gursky has played with these different energies. He positions the images in the room not only in terms of content, but also in terms of visual references, powers of attraction and repulsion, and diverse energies. He creates atmospheres in his exhibition spaces that let us move along entirely different paths, to and from, turning around, but hardly ever strolling along by the walls.

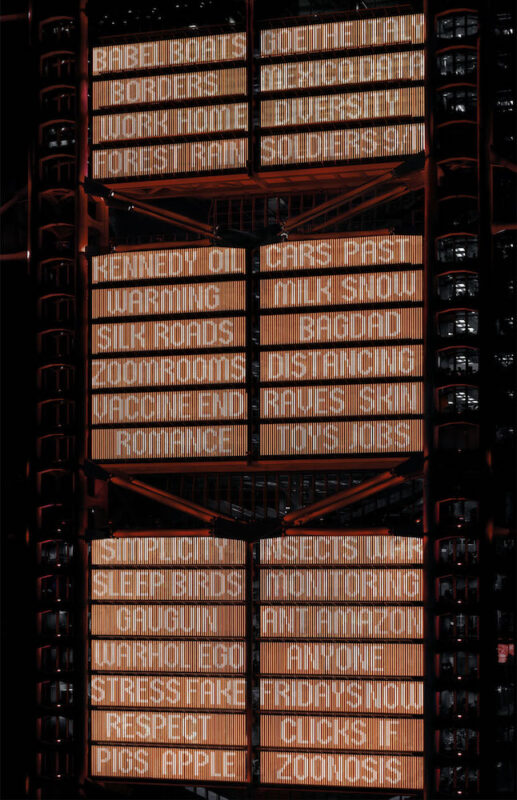

Photography is (classically) about addressing an object or being and, with that, a specific motif that appears before the camera and is set against a certain background, in a certain place, at a certain time. This form of engagement does not seem to correspond only to the attitude and style of the respective photographer, but actually appears to be inscribed into the medium of photography itself and “photo-ontologically” merged with it. It is in this spirit that Andreas Gursky travels the world, often inspired by some visual motif, situation or theme that he has seen in a newspaper. And, once his investigations have succeeded, he chooses his motif: a production plant, for instance, or the means of production in cutting-edge industries, various storage and transportation hubs such as cargo ports and warehouses, or consumer goods on display, as well as banks and stock exchanges or even traffic hotspots such as hotels, docks, and airports. He also seeks out energy production and solar power plants, aspects of tourism ranging from pleasure to sport, and even agriculture, food and meat production. He also explores the halls of politics and the temples of art. Accordingly, his photographs bear titles that are, for the most part, simple, descriptive or location-related, such as, in the first instance, Times Square, Bundesstag, Union Rave, Prada II, Engadin, Rhein or Hong Kong Stock Exchange, then Gucci, Utah, Tokyo, Pyongyang, Schweine, Politik II, and finally Kreuzfahrt (Cruise), Bauhaus, Apple, and Las Vegas.

In contrast to classic photography, however, Andreas Gursky pursues a different goal. Although he goes to these specific places, what he tries to do there is not so much to seek out and capture an attractive motif set against a backdrop – and then enlarge it to almost oversized dimensions – but instead to show situations and constellations, highlighting the underlying structures, and rendering visible the social context in which events and actions occur. He does so, on the one hand, by means of a kind of mapping in which he visually combines multiple individual details into what might be described as a photographic map, and on the other hand by condensing seemingly symbolic images that do not fully reveal their descriptive significance. Although he photographs at a specific, albeit extended, point in time, and does so at the particularly advanced venues of a prosperous, mobile, post-industrial, global society of financial capitalism – whereby landscape and nature are also to be regarded in this light in his works – he has nevertheless always sought to stretch what is fixed in time and place so that it transcends the specific, becoming universal, as though taking stock. As he said in an interview, “I am never interested in the individual, but in the human species and its environment.”[xiii] Gursky visualises many elements of globalisation, with some of its often negative effects, but he leaves the critical judgment to us, as viewers. “Yes, the issues of our time – climate change, the exploitation of natural resources, working conditions, the monopolisation of distributing structures – they’re all themes in my work. But I don’t have solutions to offer. Everyone knows that Amazon represents turbo-capitalism, but it’s for the viewers to come to their own conclusions.” [xiv]Gursky photographs global conditions of special significance, showing us the critical situations inherent in them, yet at the same time, through his images, he seeks to maintain and renew our interest in the world, its beauty, its dark sides, its complexities. In the specific, the current and the contemporary, he seeks recurrent signs of the rules and structures of global cohabitation, production, action, and order.

With regard to photography and the photographic, Andreas Gursky, over time, pushes the boundary of the medium to its limits. The 1998 image Bonn, Parliament is one of the first that he took, not using just one click, but as many as perhaps forty or fifty clicks, then digitally assembled them to create his own image of the parliament. Over time, he also shifts his viewpoint while he photographs, circling the chosen motif, zooming in and out, and then eventually combining the many elements and partial images to create the whole, as his completed image. From a purely technical standpoint, this process allows him to achieve better definition in his large-format photographs, as well as a sharper focus and greater visual saturation. Visually, this transforms the works into compositions and montages that do not immediately convey the underlying principle. As Gursky said of this in an interview: “My works are very real, and at the same time composed, but not completely imaginary. This can be seen, for instance, in the work Bahrain I (2005). The racetrack in Bahrain is made of concrete onto which a new circuit is painted for every race. That is why many of the road sections look so bizarre. This is not a figment of my imagination, but rather a figment of reality. Yet at the same time the picture is also a montage in which I have made a few changes for reasons of composition. Although the work has an increased element of perspective – the ground is steeply inclined and the composition forms an abstract pattern – there is still a horizon line and a strip of sky.”[xv] Elsewhere, he credits his teachers, Bernd and Hilla Becher, with his tendency to anchor his images with a baseline, horizon line and sky, forming the basis, orientation and anchorage of his photographs.

Andreas Gursky undertakes abstractions or constructions with regard to the image as a whole, abstracting from the specific to the general, to the systemic, or constructing a montage of multiple photographs to form an image that nevertheless strikes the viewer as familiar and normal, and even photographically true. The digital construction of the montage rarely, if ever, pushes into the foreground. Instead, it tends to emerge only through careful and close inspection. In almost monochromatic images such as the grey carpet of Ohne Titel I (1993), the sandy ground of Ohne Titel III (1996), or Amazon (2016), but also in constructed images such as Rhein II (1999), El Ejido (2017) or Beelitz (2007). It is clear that Gursky repeatedly addresses the medium of painting in his work, including American Colour field painting, Hard edge painting and Allover painting, as well as Minimalism. In subjecting his photography to these structures and to their underlying ideas and compositional approaches, he challenges his own medium and imbues it with additional potency of form. Yet he does so without ever allowing the photographs to become painterly. He is constantly seeking aspects of tension for his works – the specific and the universal, the geometrification of untamed nature, recognising and losing oneself, order and chaos, photography and painting – and tracking down crossing points within the order of the world, be they mirrored in the clarity of the absolute that is the sky, or in the midst of things, within the tangle and fullness of reality. Ultimately, Andreas Gursky is like a (highly contemporary) history painter depicting the central hubs of our life, our expressiveness, from the ecstasy of the rave to the production, structuring, administration, and interventions in our own nature. And here, especially, in this exhibition, from the port of Salerno to the Tokyo Stock Exchange, from the locker room of a coalmine to the facade of the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank, from the industrial production of meat, vegetables and flowers to the luxury goods sector or even the solar panel farm that floats across the French landscape like a gentle version of Hokusai’s Great Wave, everything everywhere is always interconnected in the vast and all-encompassing network of late capitalism.

“Perhaps that really explains Gursky’s huge success as an artist: this openness, the willingness to use everything that can serve the image and promise knowledge. Not to be fixed, either on a motive or on a way of working. […] Gursky’s pictures work as visually overwhelming, but in their entirety there is nothing triumphant,” wrote Boris Pofalla in the Welt am Sonntag. [xvi] To this day, that is what remains Andreas Gursky’s particular strength. His enormous visual power is such that entering into the universe of his images becomes each time an experience and a step towards awareness. Now, moreover, some thirty or forty years since the advent of large-format photography, this has been further accentuated by the contrast with the current spate of images in tiny 4 x 6 cm or 6 x 6 cm formats, shrunk by the use of smartphones and all similarly backlit, snapped with an attention span of no more than a second. This new world of miniature, ultrafast images has to be clear, simple and even banal so that the pictures are instantly recognisable and readable. Sadly, this leaves neither time nor space for the physical, mental and emotional exploration, experience, understanding and grasp of such images as those that Andreas Gursky offers. ♦

All images courtesy the artist and Sprüth Magers. © Andreas Gursky

Andreas Gursky. Visual Spaces of Today runs at Fondazione MAST, Bologna, until 7 January 2024 as part of Foto/Industria 2023.

_

Urs Stahel is a freelance writer, curator, lecturer and consultant. Among his current roles are Curator at Manifattura di Arti, Sperimentazione e Tecnologia (MAST), Bologna, Italy; Consultant of the MAST collection of industrial photography; Adviser to the Vontobel Art Collection and Adviser to Foto Colectania, Barcelona, Spain. As the Co-Founder of Fotomuseum Winterthur, Switzerland, he worked there as Director and Curator between 1993–2013. He lives and works in and out of Zurich, Switzerland.

Images:

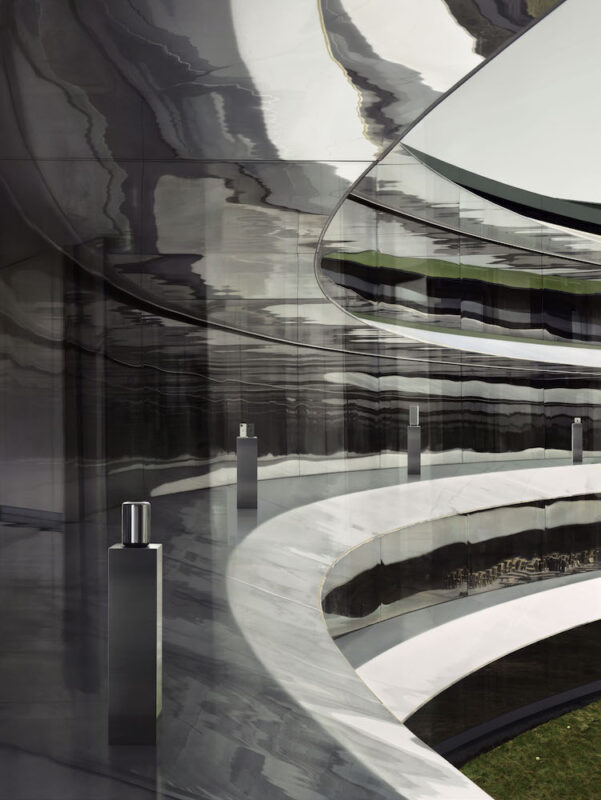

1-Andreas Gursky, Amazon, 2016. © Andreas Gursky, by SIAE 2023 Courtesy: Sprüth Magers

2-Andreas Gursky, Apple, 2020. © Andreas Gursky, by SIAE 2023 Courtesy: Sprüth Magers

3-Andreas Gursky, Bahrain I, 2005. © Andreas Gursky, by SIAE 2023 Courtesy: Sprüth Magers

4-Andreas Gursky, F1 Boxenstopp I, 2007. © Andreas Gursky, by SIAE 2023 Courtesy: Sprüth Magers

5-Andreas Gursky, Hong Kong Shanghai Bank III, 2020. © Andreas Gursky, by SIAE 2023 Courtesy: Sprüth Magers

6-Andreas Gursky, Kodak, 1995. © Andreas Gursky, by SIAE 2023 Courtesy: Sprüth Magers

7-Andreas Gursky, Les Mées, 2016. © Andreas Gursky, by SIAE 2023 Courtesy: Sprüth Magers

8-Andreas Gursky, Salerno, 1990 © ANDREAS GURSKY, by SIAE 2023 Courtesy: Sprüth Magers

9-Andreas Gursky, Salinas, 2021. © Andreas Gursky, by SIAE 2023 Courtesy: Sprüth Magers

10-Andreas Gursky, Tokyo Stock Exchange, 1990. © Andreas Gursky, by SIAE 2023 Courtesy: Sprüth Magers

11-Andreas Gursky, V&R II, 2022 (2009). © Andreas Gursky, by SIAE 2023 Courtesy: Sprüth Magers

References:

[i] https://www.republik.ch/2018/10/02/analphabetendes-bildes (access: 16 March 2023).

[ii] Although Ansel Adams had printed the image more than a thousand times.

[iii] Last year, in 2022, that record was broken. Man Ray’s Le Violon d’Ingres (1924) was sold at Christie’s in New York for 12.4 million dollars.

[iv] Louise Lawler, Why Pictures Now, 1981.

[v] Richard Prince, Why I Go to the Movies Alone, p. 11. http://www.richardprince.com/writings/why-i-go-to-themovies-alone-pg-3-6/ (access: 16 March 2023)

[vi] John Szarkowski, Photography Until Now, catalogue of the exhibition, Museum of Modern Art New York, New York 1989, p. 269.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Jean Baudrillard, Simulacre et Simulations, Editions Galilée, Paris 1981 (English translation: Sheila F. Glaser, UMP, Ann Arbour 2002).

[ix] Michael Wetzel, Paradoxe Intervention. Jean Baudrillard und Paul Virilio: Zwei Apokalyptiker der neuen Medien, in Ralf Bohn, Dieter Fuder (ed.), Baudrillard. Simulation und Verführung, Fink, München 1994, p. 97.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Tilman Osterwold, Blow-Up. Zeitgeschichte, exhibition catalogue, Württembergischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart 1987.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Liz Jobey, “Andreas Gursky: The perfect image is not something that can be taught,” in Financial Times, online, January 12, 2018 (access: 16 March 2023)

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Andrew Maerkle, “Andreas Gursky,” in Art it, July 12, 2013 https://www.art-it.asia/en/u/admin_ed_itv_e/E6vMIYKmWUG5q8NJVQrS/ (access 16 March 2023).

[xvi] Boris Pofalla, “Ich war so ein Spätachtundsechziger,” in Welt am Sonntag, March 21, 2021