Arwed Messmer

Zelle/Cell

Book review by Gerry Badger

In 1977, Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel produced their famed book entitled Evidence, in which a collection of anonymous photographs from government and corporate archives – presented without commentary – looked liked an exhibition of images by the latest young art photographers. It demonstrated that, with most photographs, it is usage rather than aesthetics that matters. Sultan and Mandel introduced archive imagery into the aesthetic discourse, and thereby aestheticised it – made it art.

This is the area in which German photographer Arwed Messmer also operates. For a number of years, he has had privileged access to various German state archives, including those of the former DDR. He has produced various projects mining this rich material, including one made with Annett Gröschner, Taking Stock of Power. An Other View of the Berlin Wall. Here, Messmer created panoramas from negatives made of the Berlin Wall in the 1960s, made from the DDR side, and combined this with other archive material, including a series of watch towers that out-Bechered the Bechers. Now he is particularly interested in the left-wing terrorism of the 1970s and 80s as evinced by his latest publication Zelle/Cell, as well as an exhibition this June at Museum Folkwang, Essen, entitled RAF: No Evidence / Kein Beweis.

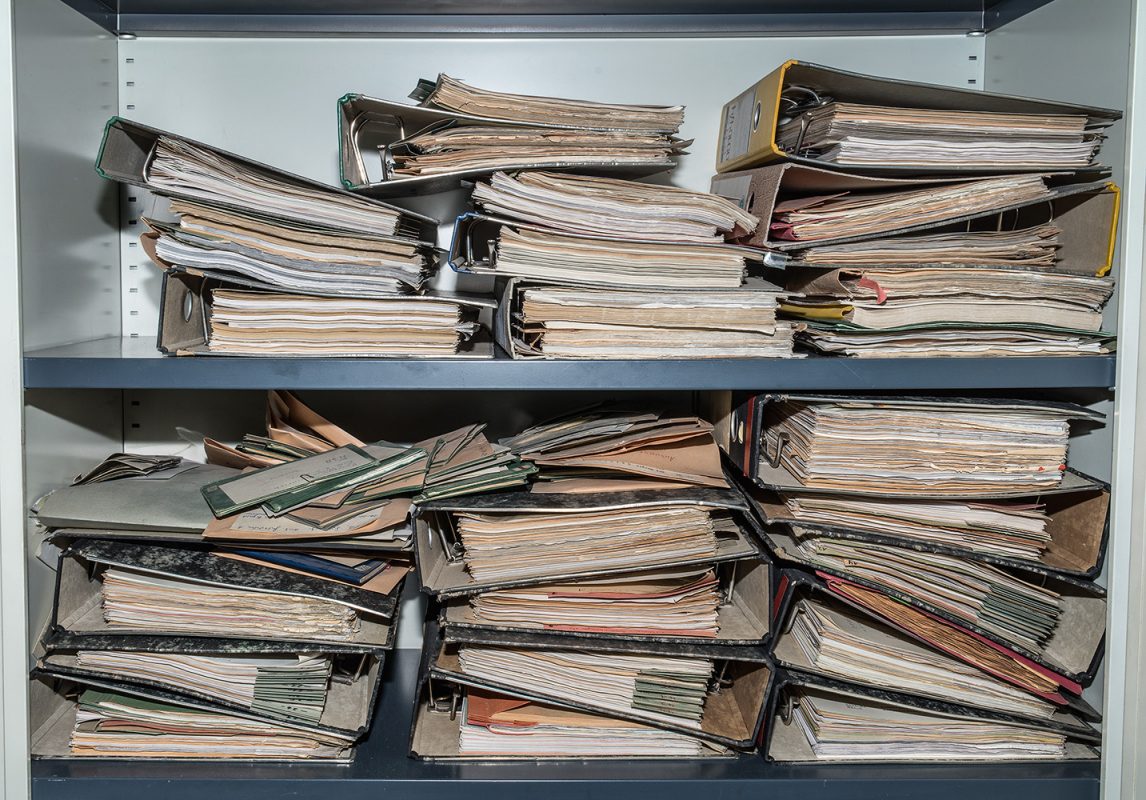

As with Sultan and Mandel, the aesthetic element is there, but Messmer’s artistic intentions are more complex. He is clearly asking questions about the archive, about all this photographic material held by the state, not necessarily for nefarious purposes, but largely because, like the vast new Internet archive, it is simply there. Nefarious – maybe not, but as Sultan and Mandel say – it is evidence. It is also, to one extent or another – surveillance.

On February 27, 1975, a prominent West German politician, mayoral candidate Peter Lorenz, was kidnapped by one of those revolutionary groups that so haunted that decade, the Movement 2 June group. Next day, the gang sent a Polaroid picture of a shocked and battered looking politician, holding up a sign to prove its legitimacy. The picture, like a similar one of the kidnapped Italian politician, Aldo Moro from the following year, became one of those symbols of the 70s – iconic, to use this overused and now devalued word. But unlike Moro, who was left to rot by his own party and eventually murdered, Lorenz was freed after a deal was made to release the prisoners demanded by the kidnappers. It is this image around which Messmer constructs his narrative. But, while well-known, it is one of many, taken from an extensive archive of 3,000 police negatives, and yet many of the written files and object evidence had been destroyed, so these hitherto unexamined photographs bear the burden of the story – a story which, as Messner says is “non-linear.” He is not attempting to reconstruct the history but play creatively, as it were, with this fascinating, but enigmatic material. His concern, as Ines Linder puts it in the book’s accompanying essay, is ultimately with “the language of the photographs.”

Messmer begins with a suite of photographs depicting the incident which gave the Movement June 2 its name. During a student demonstration on June 2, 1967, against a proposed visit to West Germany by the Shah of Iran, a student named Benno Ohnesorg was shot in the head by a police officer who later was revealed as an East German Stasi agent – in “self defence” of course. The photographs show the aftermath of what was nothing less than murder – but instigated by whom? The images show shocked bystanders, police officers not knowing what to do, a woman tenderly cradling the dying man. Using direct flash, the aesthetic reminds one of Garry Winogrand, but this isn’t art, it’s reality.

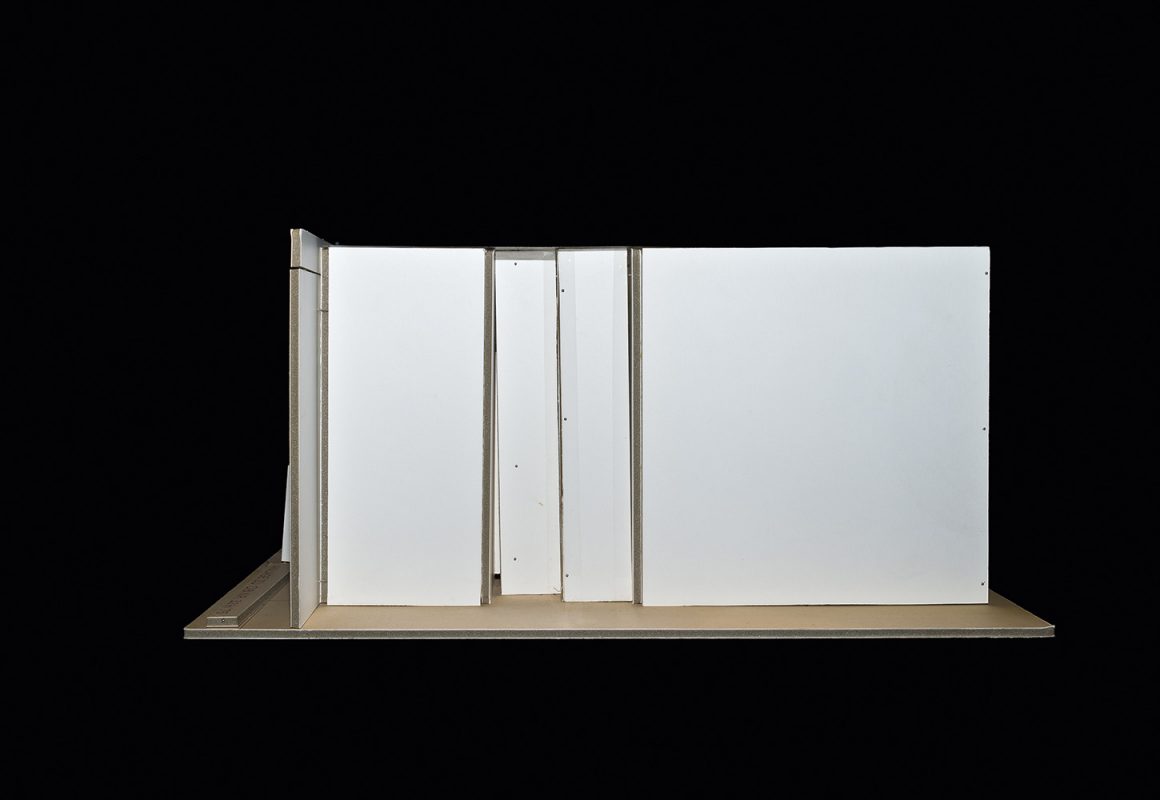

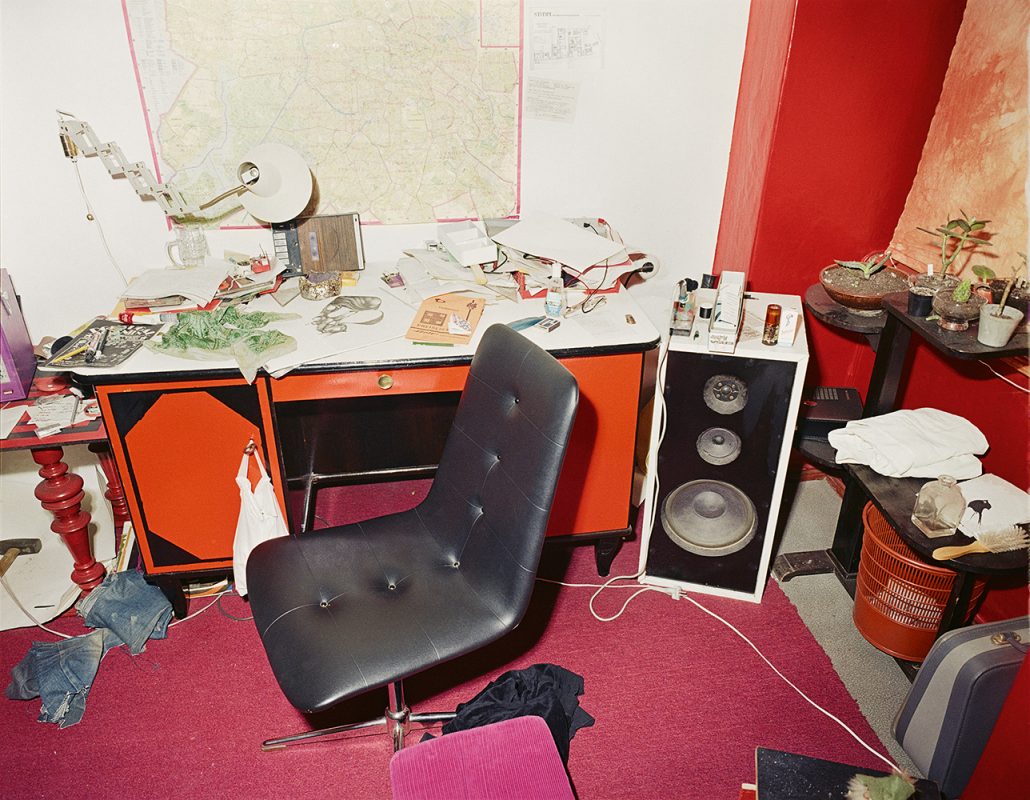

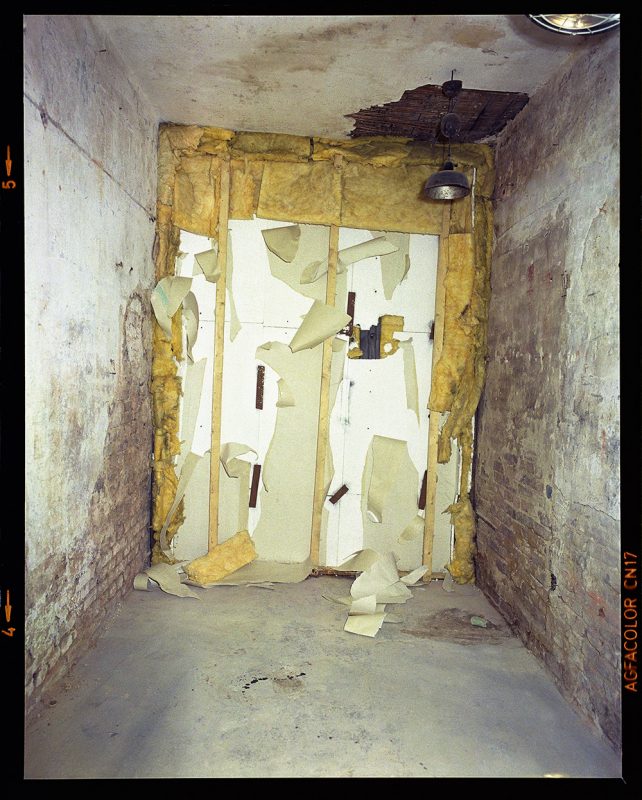

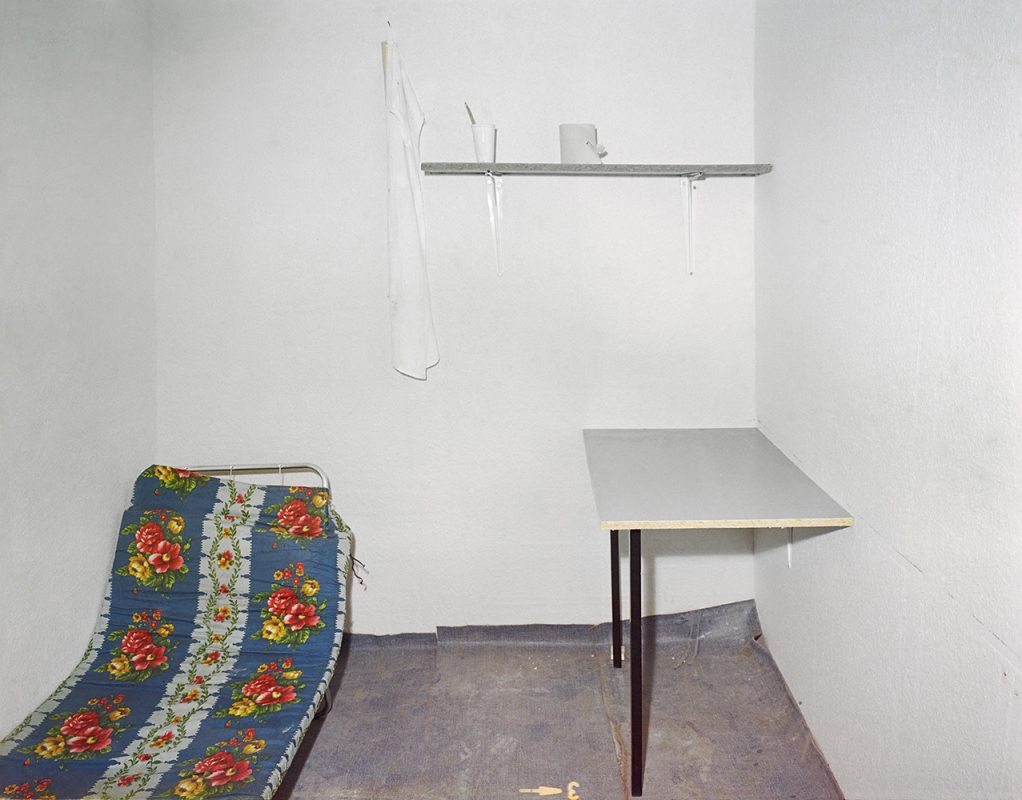

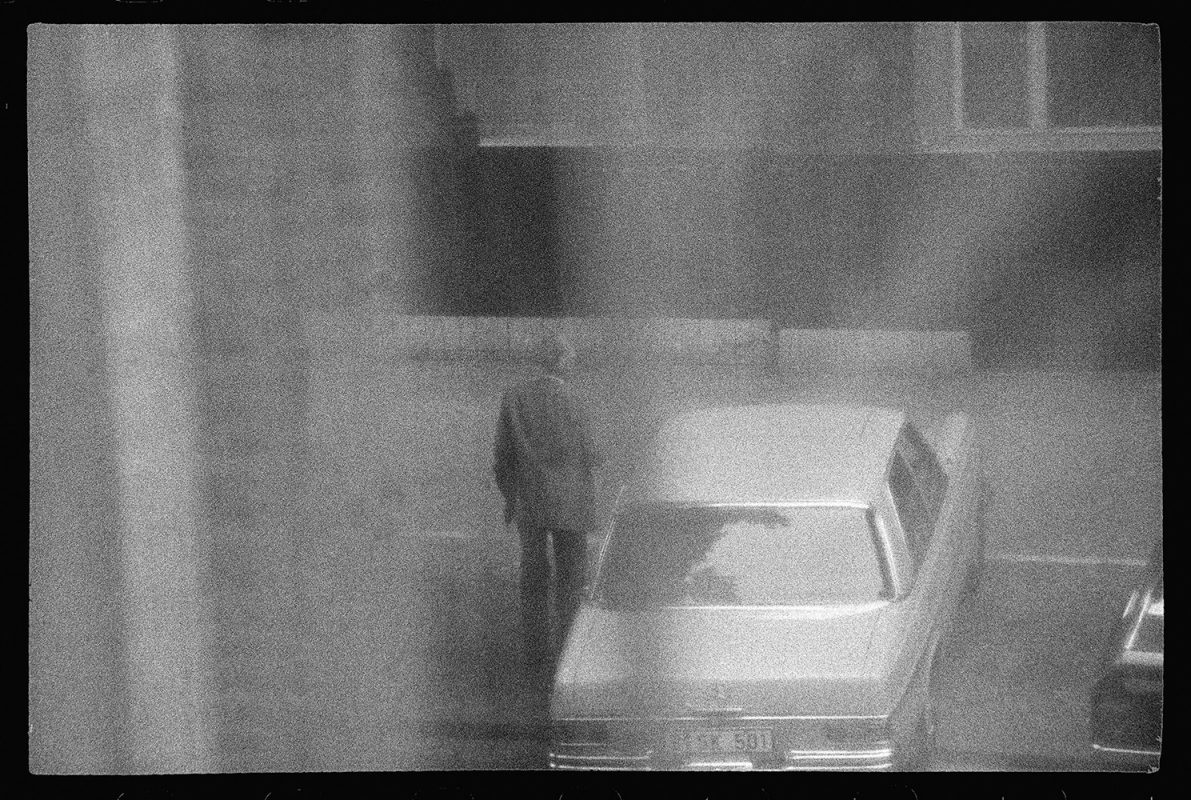

This is followed by similar, press-photo style pictures of two of the people released in accordance with the Lorenz kidnappers’ demands, taken to Tegel Airport to be flown to Yemen. And then the fun begins. Firstly, Messmer photographed a model made of the ‘cell’ under a bric-a-brac store in Kreuzberg where Lorenz was detained, followed by a variant of the famous Polaroid. Thereafter, there is an almost bewildering sequence of images – of getaway cars, the location where Lorenz was released, and his basement cell. One particularly intriguing sequence – again out-Bechering the Bechers, shows a series of sheet materials used to soundproof the Lorenz cell. There are images of weapons, mug shots, fingerprints lots of interiors with piled up detritus – terrorists are a squalid lot, as the Daily Mail would say – and one intriguing shot of a broom left at the scene of the kidnapping. One of them, it seems disguised himself as a street cleaner. Squalid, not him.

Messmer deliberately alters the chronology of events, and you need to look at the captions in the rear to make sense of things. But that is not the point. Messmer is questioning photography’s role, both as witness, and ultimately, as art. As Ines Linder again points out: “The super cool style of crime scene, medical, or military photographs communicates with our imaginations in a very idiosyncratic manner when these images are not contextualised in a narrative.”

Even when contextualised into a narrative, the photograph communicates in ways that are not only idiosyncratic but sometimes downright baffling. The more I get into photography – and that journey represents more than four decades of my life – the less I am interested in arty-farty photography, in a word, pictorialism, and the more I am fascinated by how photography intersects with history. That necessarily means documentary photography, but not necessarily ‘documentary’ photography in its strictest definition. It might mean photocollage, or constructed photography, or art utilising photographs. As long as it intersects with history it becomes interesting. For photography in general does not intersect with history in a straightforward manner since all photography eventually becomes history, but again, not necessarily history as we know it. Some photography clearly portrays history directly. However, not as much as we might think so one could say photography excels most at providing history’s footnotes. In the main, the historical connection is oblique, confusing, slippery, inconclusive, often unreliable, but always highly intriguing. As this superbly conceived and executed book amply demonstrates. It shows art clashing with history – with art just winning out on points. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Arwed Messmer, using negatives from the Police Historical Collection Berlin (Lorenz files).

—

Gerry Badger is a photographer, architect and photography critic of more than 40 years. His published books include Collecting Photography (2003) and monographs on John Gossage and Stephen Shore, as well as Phaidon’s 55s on Chris Killip (2001) and Eugene Atget (2001). In 2007 he published The Genius of Photography, the book of the BBC television series of the same name, and in 2010 The Pleasures of Good Photographs, an anthology of essays that was awarded the 2011 Infinity Writers’ Award from the International Center of Photography, New York. He also co-authored The Photobook: A History, Vol I, II and III with Martin Parr.