Top 10

Photobooks of 2016

Selected by Tim Clark

An annual tribute to the most exceptional photobook releases from the year that was – selected by our Editor in Chief.

1. Gregory Halpern: ZZYZX

MACK

Once the hype subsides, and you let Gregory Halpern’s images bathe you in glorious California sunlight, it’s clear to see why ZZYZX was named Photobook of the Year at The Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. MACK’s production is sumptuous and as far as photography goes Halpern’s is of the highest order.

The book takes us on a journey, starting at the desert east of Los Angeles, across the city and up to the Pacific Ocean but seen through the filter of Halpern’s ineffable vision, it is in fact more akin to somnambulation. Images depict odd characters and quiet moments – things observed, rendered through description and suggestion – which on accumulation build up a picture of a sort of Babylon on the brink of collapse. With an untold narrative, contained but concealed, we slowly feel the burning desire for a place; a dreamed-of place since, as Italo Calvino one wrote, “desires are already memories”.

2. Edmund Clark and Crofton Black: Negative Publicity

Aperture/Magnum Foundation

Part research document, part exhibition catalogue and part dossier, Negative Publicity presents a complex and multi-layered reflection on the CIA’s programme of ‘extraordinary rendition’. Clark has turned his camera to spaces and surfaces that contain a hidden, violent tension, those which stand in for the countless people who have disappeared into a mysterious prison network – the vanishing point for the law. Yet no drama is pictured here, just the drama of a picture. Collaborating with counter-terrorism expert Crofton Black, he has paired images and redacted documents to interrogate the nature of contemporary warfare and invisible mechanisms of state control. A book that really matters.

3. Sara-Lena Maierhofer: Dear Clark; Portrait of a Con Man

Drittel Books

Sara-Lena Maierhofer has made it her business to tell the tale of a real-life imposter who went by the name of Clark Rockefeller, among other personas, having passed himself off as a scion of the wealthy family. Dear Clark pieces together remnants of his life, through material such as birth certificates, brain scans and family photographs alongside images that speak to key themes of multiplicity and transformation. The book’s material qualities are almost akin to installation with design touches like tipped-in images that perfectly heighten the searching quality of the project. Reality and fantasy, fact and fiction are masterfully at play here as Maierhofer makes tremendous art out of deception and the corrosive effects of lies.

4. Michael Hoppen Gallery: Evidence Case File

Guiding Light

This richly illustrated, cleverly designed book offers a small but brilliant insight into the collection of reknown photography dealer Michael Hoppen. In parallel to The Image as Question: An Exhibition of Evidential Photography, recently on display at the eponymous London gallery, it sets out to disturb the big claims of photography as ‘record’ or ‘proof’. A judicious selection of works harks back to the medium’s 19th century origins and also includes images from 20th century stalwarts as well as contemporary artists. The book empties images of their original evidential function and reconceptualises them in a new context and in a new time. Questioning what a ‘fact’ is a well-trodden area of investigation yet the presentation, editing, sequence and paper choices are very well-measured and all equally important to the publication as various parts separately. Rewards the curious.

5. Laia Abril: Lobismuller

Editorial RM/Images Vevey

Laia Abril is continually on the up and the photobook has always been an essential part of her output. Just recently-released, Lobismuller sees the Catalan artist produce a meditation in photography and text upon Spain’s first documented serial killer. The Werewolf of Allariz, known as Manuel Blanco Romasanta was originally named Manuela since it was initially believed he was a woman. This central figure was also dubbed the ‘Soapmaker’, owing to his habit of using the fat of victims to produce high-quality soap. Gender issues, psychology, landscape, mythology and folklore… the mesmerising story is wrapped upon layer of exquisite literary narrative. Between each image and each piece of text, a creepy affinity can be established, demonstrating Abril’s fluidity between medium and genre, which has come to characterise her practice.

6. Todd Hido: Intimate Distance

Aperture

This is a lavish monograph befitting one of the most influential US photographers. Todd Hido’s unique brand of cinematic spectatorship is surveyed en masse in Intimate Distance, bringing together twenty-five years of photographs full of substance and thickness of atmosphere. The book tracks the development of a career via Hido’s overlapping motifs and preoccupations: disarming nudes, smudged landscapes and interiors or housing lit up as if glowing chambers, inviting us to consider his world-as-image and rethink his oeuvre from a fresh perspective. The need to know oneself and the fear of self-knowing find their beautiful expression here. His is an art of longing.

7. Francesca Catastini: The Modern Spirit is Vivisective

AnzenbergerEDITION

“Knowledge is not made for understanding, it is made for cutting,” reads the Michel Foucault quote that appears in the postscript to Francesca Catastini’s The Modern Spirit is Vivisective. It serves as a useful coda for considering the work. True to its title, this handsome book is an investigation into the process of studying human anatomy, combining the artist’s own photographs with vernacular images of old anatomy lessons, illustrations from Renaissance manuals, complemented with scientific, literary, and philosophical texts. Using chapters as its organising system – On Looking, On Canon Lust, On Touching, On Cutting, On Discovering – the book reveals a great capacity for sequencing images, and the possibility to conceive of them as a form of literature.

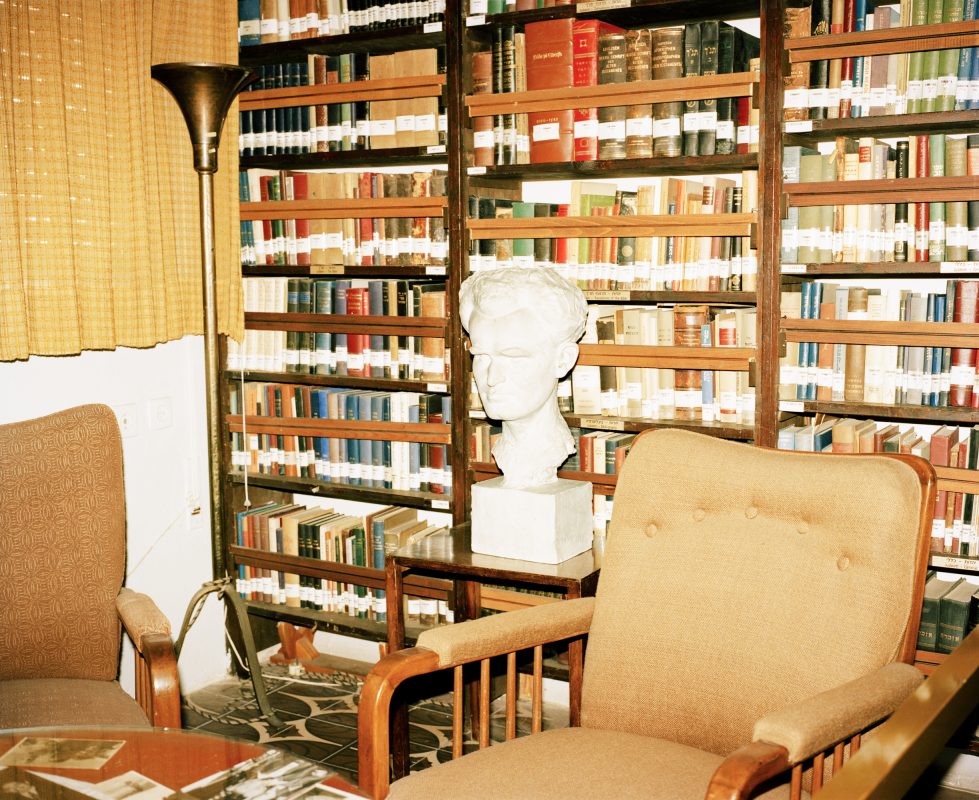

8. David Fahti: Wolfgang

Skinnerboox

Gathered on the pages of David Fahti’s Wolfgang are black and white photographs sprinkled with quotations from Wolfgang Pauli, a pioneer of quantum physics also held responsible for a large number of unexplainable failures of equipment at the CERN laboratory in Switzerland. Countless accidents, surprises and flashes of unlikely beauty and absurd humour work to conjure up Pauli’s omnipresence despite his absence in the images. Skinnerboox enlisted celebrated book designer Ramon Pez to step in and around the project and the production is all the better for it. A sum of its wonders; art, design, photography, science and history collide and fuse together to powerful effect.

9. Tito Mouraz: The House of The Seven Women

Dewi Lewis Publishing

Misty forests, bemused animals, brooding portraits and delipidated out-houses are just some of the gothic-infused imagery on display in Tito Mouraz’s The House of The Seven Women. They are visual elements invoked to give material form to a myth of the Beira-Alta region of Portugal, where the photographer was born and raised – that of a house believed to be haunted by the ghosts of seven sisters, including one witch. Strange happenings were said to occur on the occasion of a full moon, namely the women would fly from their balcony to a tree opposite and seduce passers by. An eerie and enigmatic mood piece, the work translates brilliantly to book form, classical and full of craft.

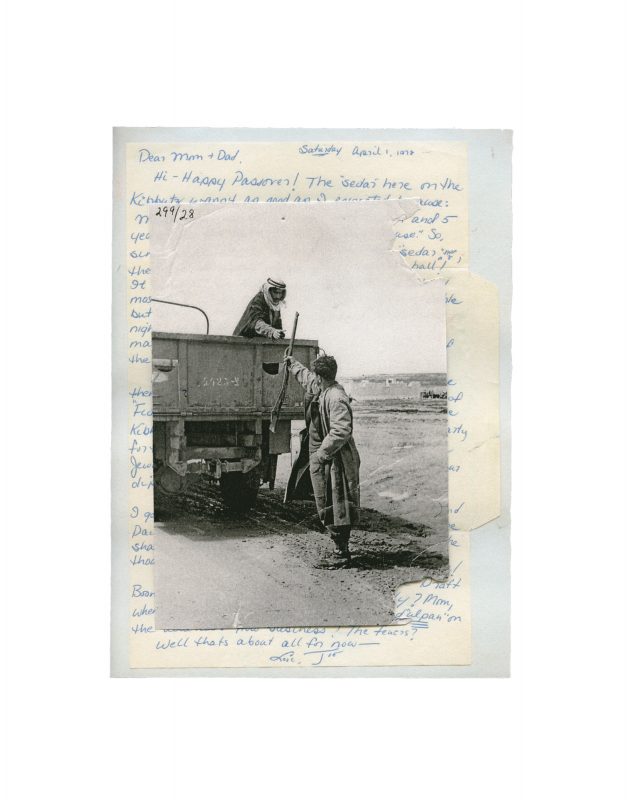

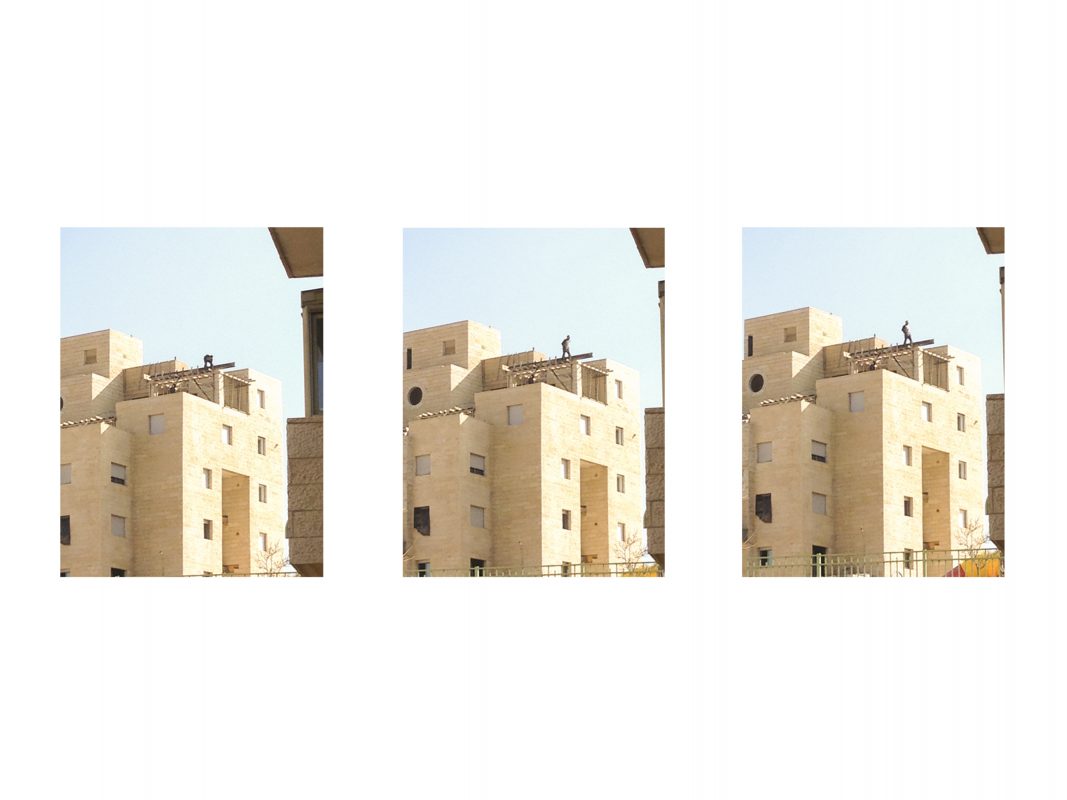

10. Adam Golfer: A House Without a Roof

Booklyn Press

The complicated histories of founding the state of Israel and the subsequent violence and displacement of Palestinians as a result of military occupation serve as the subject for this debut book from photographer Adam Golfer. A House Without a Roof draws on his own personal past and familial connections to the place to form an interesting, first person perspective while foregoing any conclusion about its troubled present. This is not easily reducible or categorisable work and Golfer deftly blends Internet-sourced imagery, archival material and extensive use of text with his photographs of the ongoing conflict, as seen at ground level. At least, it transmits the disorienting sense of an outsider locating oneself within a historic ‘home’, constructed through both real and imagined narratives. ♦

—

1000 Words Julia Margaret Cameron: Influence and IntimacyGathered Leaves: Photographs by Alec SothPeter Watkins: The UnforgettingRebecoming: The Other European TravellersFOAMTIME LightboxThe TelegraphThe Sunday TimesPhotoworksThe British Journal of Photography