Paris Photo 2022

Top six fair highlights

Selected by Alessandro Merola

Within the Grand Palais Éphémère, Paris Photo 2022 is now underway. This year’s offerings are more diverse and demanding than ever, making it a great litmus test for what is going on in the medium today. Here are six standout displays from the fair’s 25th edition – selected by 1000 Words Assistant Editor, Alessandro Merola.

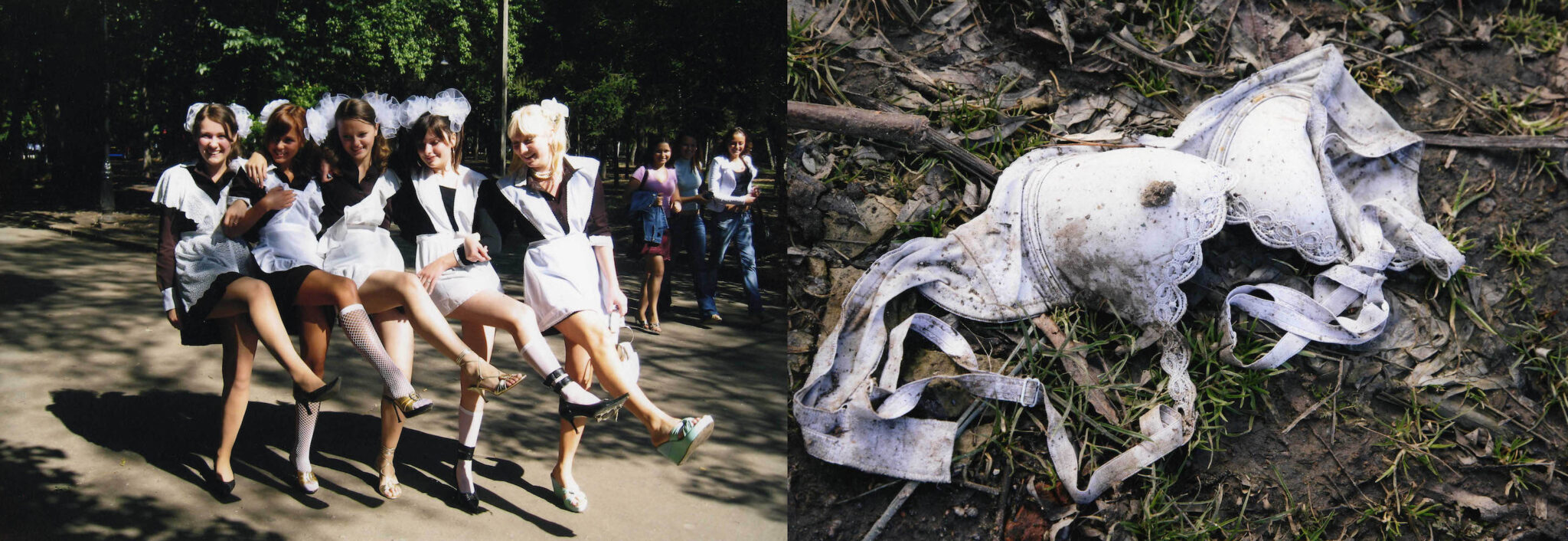

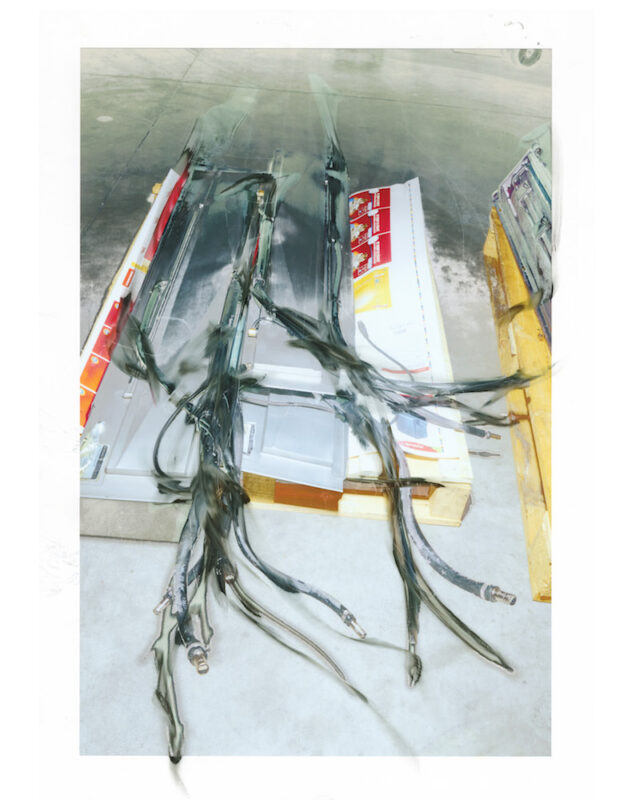

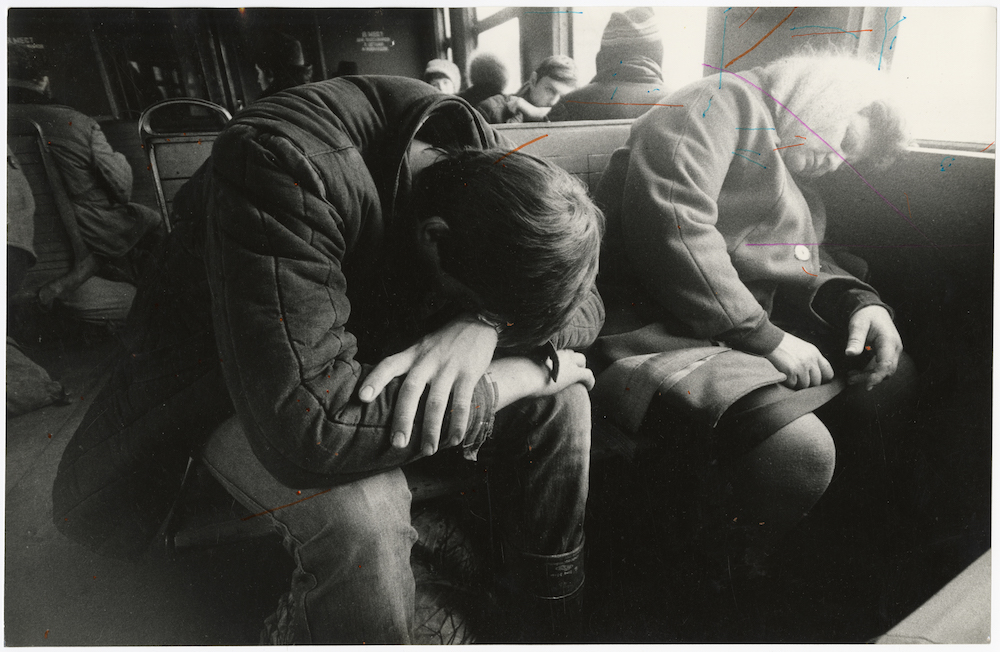

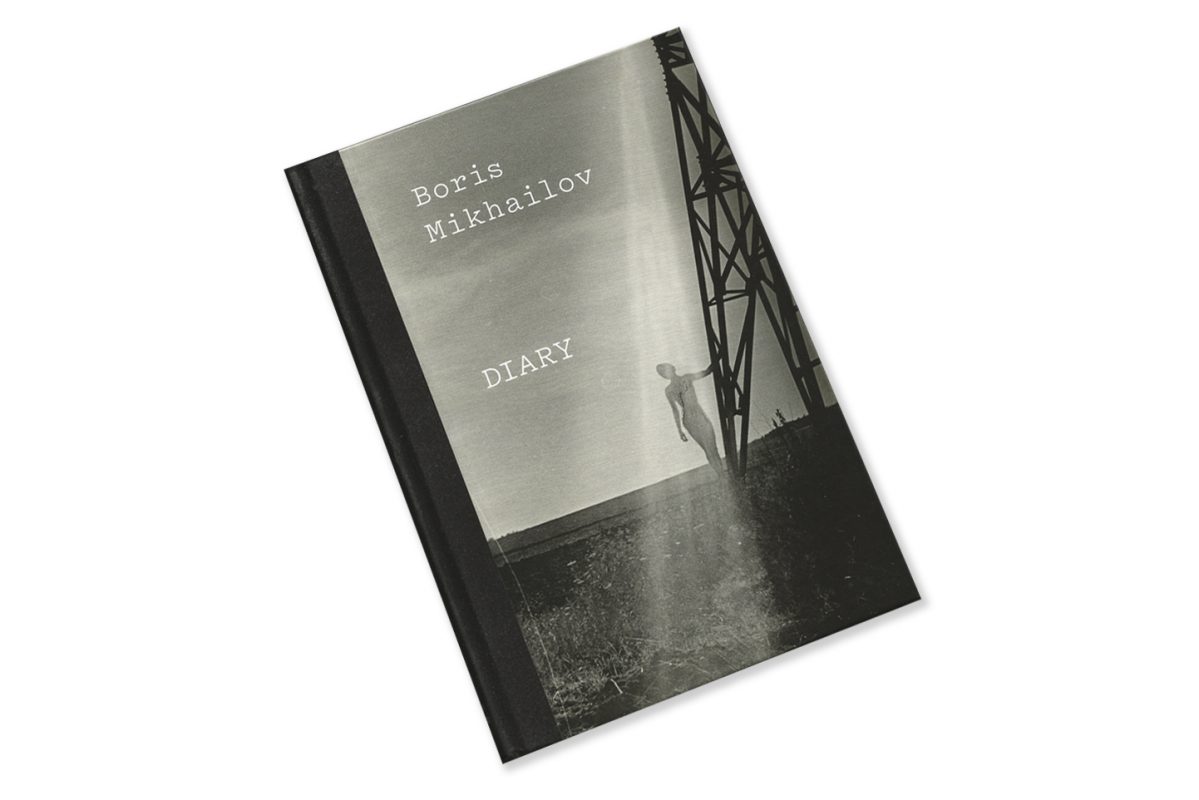

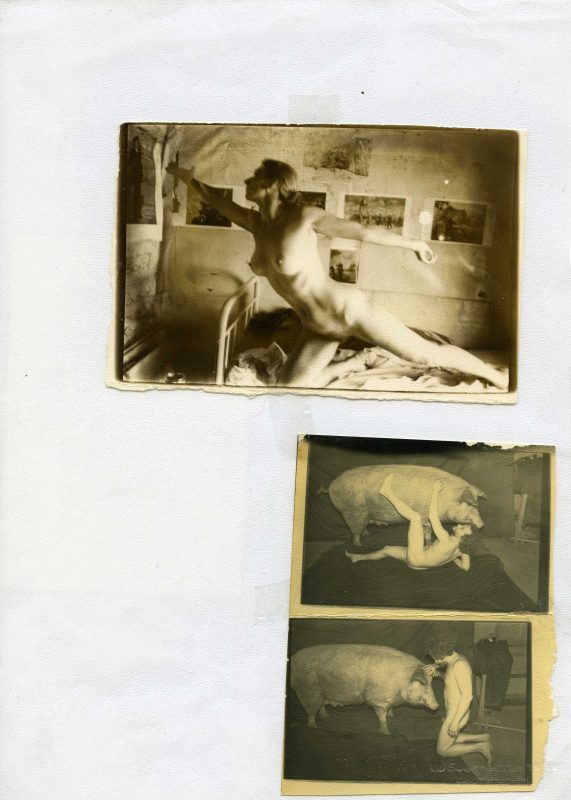

1. Boris Mikhailov, The Theatre of War, Second Act, Time Out

Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve

Paris’ multiple tributes to Boris Mikhailov, in the form of his retrospective at MEP and the haunting presentation of At Dusk at the Bourse de Commerce’s Salon, continue to take on new meanings following Vladimir Putin’s razing over the Ukrainian photographer’s hometown of Kharhiv. Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve’s decision to show The Theatre of War, Second Act, Time Out (2013), a rarely exhibited record of Ukraine’s slide into war, is a strong one. Produced during the wave of pro-European demonstrations in Kyiv’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti, these on-the-ground shots depict life behind the barricades – what the artist refers to as a “stage set”. Indeed, the Stalinist square, after which the movement was named, had been rebuilt in the 1930s as a set piece to glorify – or appeal to the memory of – revolution. But what we find here are the architects of a real revolt, ushering in the transformation of a state both deeply ambitious and tragically incomplete. In this regard, the inclusion of prints from Tea, Coffee, Cappuccino (2000–10), chronicling the colourful, plastic realty of Kharhiv in the era of new capitalism, both reflects and disturbs this story. No photographer has captured the complexity of Ukraine’s post-Soviet psyche as eloquently as Mikhailov, whose aesthetic sublimations have kept him on the inside of history, looking out.

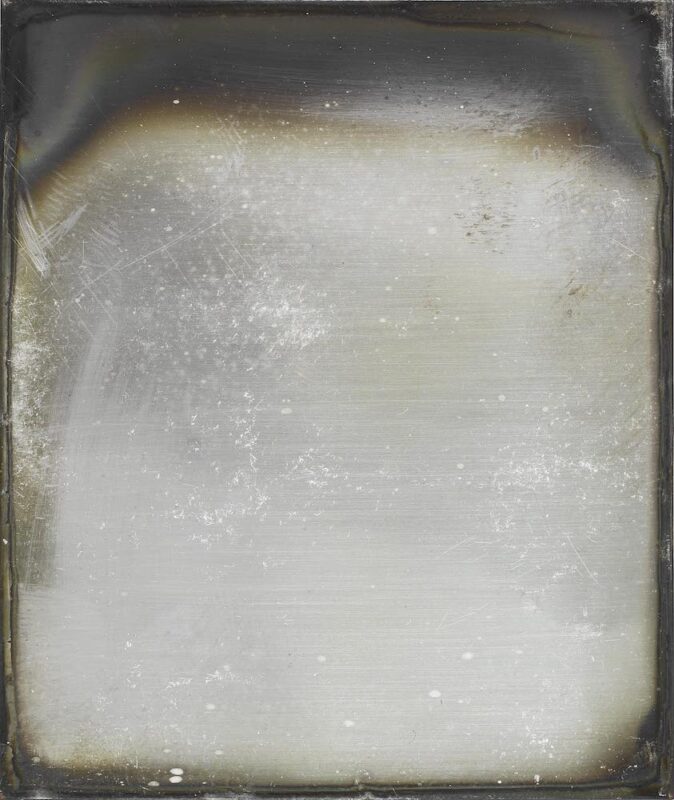

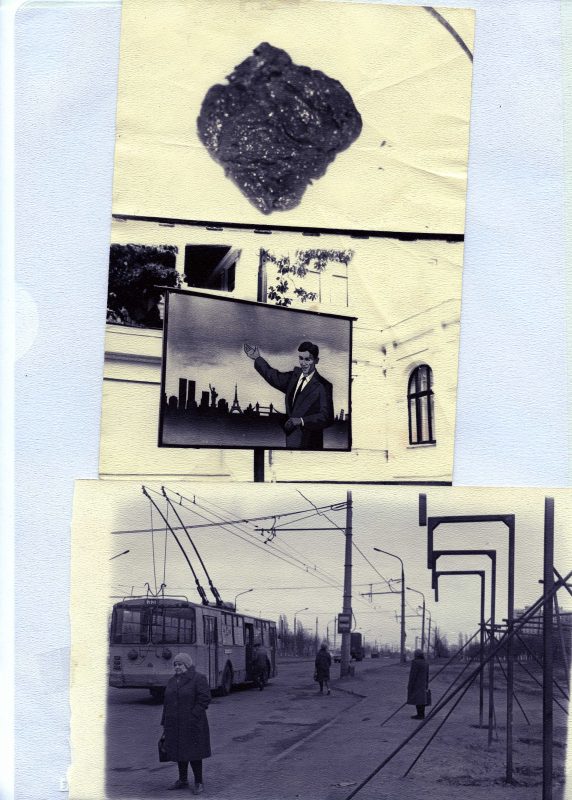

2. Jean-Kenta Gauthier, Real Pictures: An Invitation to Imagine

Offering a sensitive dimension to erasure, memory, imagination et cetera – the themes that underpin Jean-Kenta Gauthier’s booth, which feels more like a mini-exhibition – is the installation of Real Pictures (1995) by Alfredo Jaar, who lays to rest the post-traumatic content of his Rwandan photographic encounters by entombing them in black boxes. The site contains a certain sorrow that can only be understood once you read the texts on the boxes, factually describing the photographs. The Real refers to a failure, or impossibility, of representation which sustains Jaar’s engagement with the subject matter of genocide. Whilst Daido Moriyama takes us back to the “beginning” of photography through a shot of his Tokyo bedroom in which Nicéphore Niépce’s “fossilised” View from the Window at Le Gras (1827) hangs (the clock reads 11:03, one minute after the Nagasaki bomb, as memorialised by the melted pocket watch of his mentor, Shōmei Tōmatsu), Hanako Murakami takes us back even further still via Louis Daguerre, whose words, now ignited in neon, “I am burning with desire to see your experiments from nature”, penned in a letter to Niépce. The statement becomes troubled alongside Murakami’s take-free paper stack which cleverly condenses Niépce’s 1829 treatise on the invention of heliography to its front and back covers, respectively illustrating both sides of a single sheet. Murakami’s ongoing, richly researched and poetic archaeologies of the past remind us that the history of photography is full of absences. By questioning the origins of the medium, she questions the memory of the world.

3. Noémie Goudal

Galerie Les filles du Calvaire

The fragile instability of the world humans desire to see is intelligently interpreted by Noémie Goudal, whose dynamic presentation at the group show of Galerie Les filles du Calvaire really stands out. The complexity of Goudal’s interventions reside in the way it implicates the audience – both visually and spatially – in her fabrications of nature. For example, it is only upon a close inspection that her large snow-capped mountain peak images reveal themselves as paint-coated concrete slabs mounted on cardboard; their initial illusory vastness thus become vertiginous. Yet, if Goudal attempts a trompe-l’œil, it is intentionally flawed, for she does not set out to conceal the models’ constructedness, but instead puts it centre-stage. Her manipulations are even more ambiguous in Décantation (2021), which, on the contrary, are most impactful when viewed from afar. Achieved through a process of printing on water-soluble paper and rephotographing, small, subtle iterations narrate an imaginary washing-out – or “dissolving” – across time. Over the suite of photographs, the rock formations melt, like glaciers. It’s here that Goudal, chillingly, shows us the complicity between the desire to see and the desire to destroy.

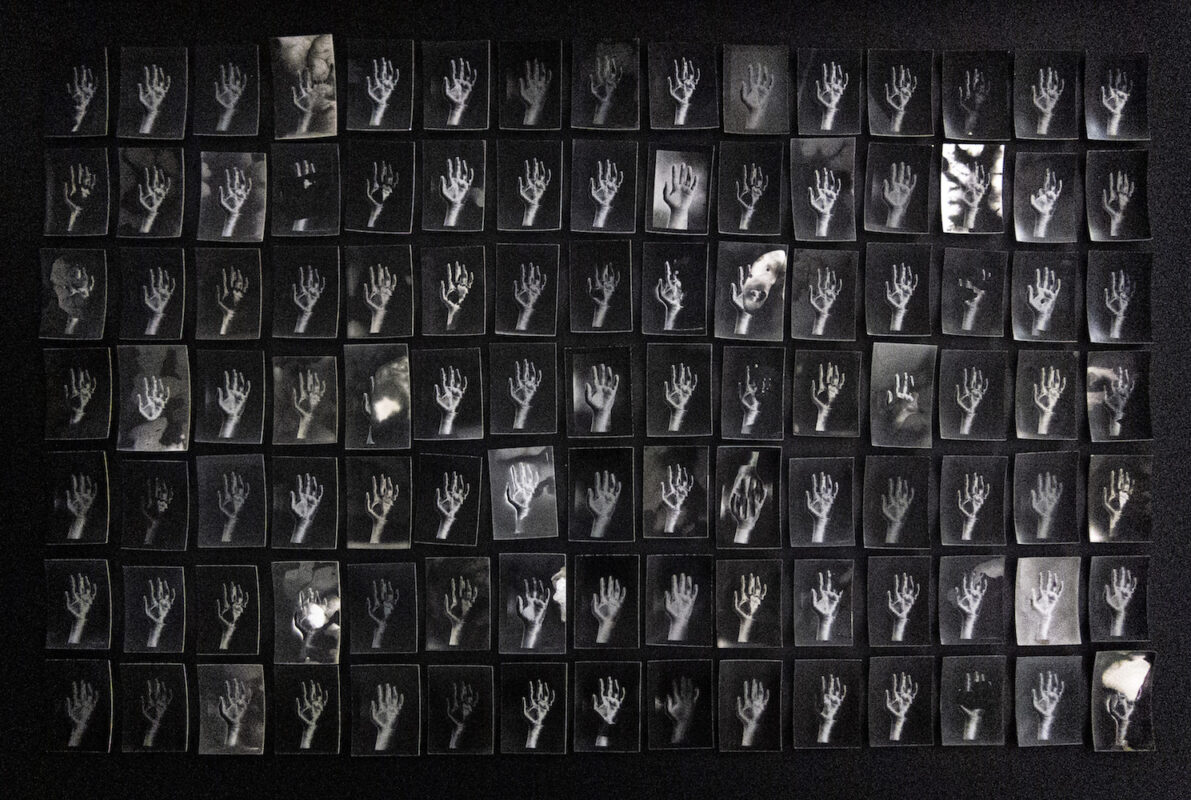

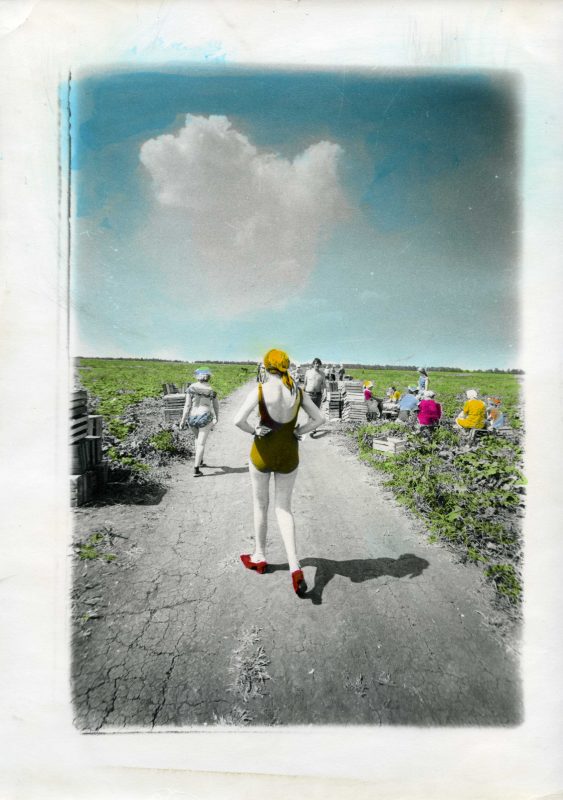

One of the toughest and most transcendental viewings at this year’s fair comes from Cannon Bernáldez’s El estado normal de las cosas (2022), which is on show at Mexico City’s Patricia Conde Galería. Translating to The normal state of things, the piece sees Bernáldez communicate her experience of being assaulted through the language of fragmentation: an arrangement of 105 silver gelatin prints each depict her wounded hand. By way of burning as well as solarising – extreme, continuous and multiple overexposures of the photographic film – Bernáldez touches on the violence of inhabiting a physical, female body. Just as symbolically loaded is the work of Yael Martínez, represented here by a grid of nine new photographs that tell a dark and fractured tale of contemporary life in Mexico. For all his sublime, fantastical lyricism, Martínez channels an attuned physicality, spirit of resistance and sense of rootedness. Meanwhile, there is a special opportunity to view a portfolio of delectably printed Mary Ellen Mark photographs documenting vibrant happenings at Mexican circuses. Their joyousness and eccentricities make it clear why Mark considered the circus “a metaphor for everything that has always fascinated me visually.”

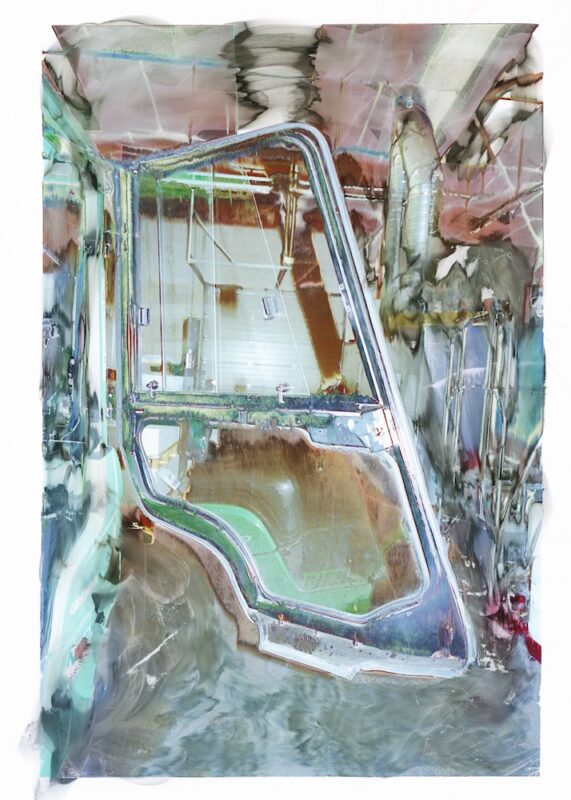

5. Jean-Vincent Simonet, Heirloom

Sentiment

Since its inauguration in 2018, the Curiosa sector has been charged with injecting cutting-edge elements into the fair. And this year is no different as Holly Roussell’s energetic curation certainly continues in this vein. Jean-Vincent Simonet’s meta-experiments that form Sentiment’s booth are interesting because they fuse analogue photography and digital techniques in a way that feels more terminal than future. Comprising a classic hang of 12 unique pieces – images of, and made at, the printing factory that has belonged to the artist’s family across three generations – Heirloom (2022) turns its attention to the instruments of production: ink tanks, paper trash and cleaning tools. Whilst they lack the exuberant, excessive fetishism of his fashion work and nudes, they retain all the entropic impulsivity and vivid luminosity that makes Simonet’s work so seductive. Using and abusing industrial printers – through what appears to be a frenzied combination of false settings, plastic foils, drying, washing, rinsing and fingertip smudging – Simonet has manufactured and modified images that bear an uncanny resemblance to painting. Although the ink sometimes seeps into the white bleed, their “aliveness” is actually deceptive, for the lead frames bestow a sense that what we are really looking at are reliquaries: elegiac witnesses of an approaching demise.

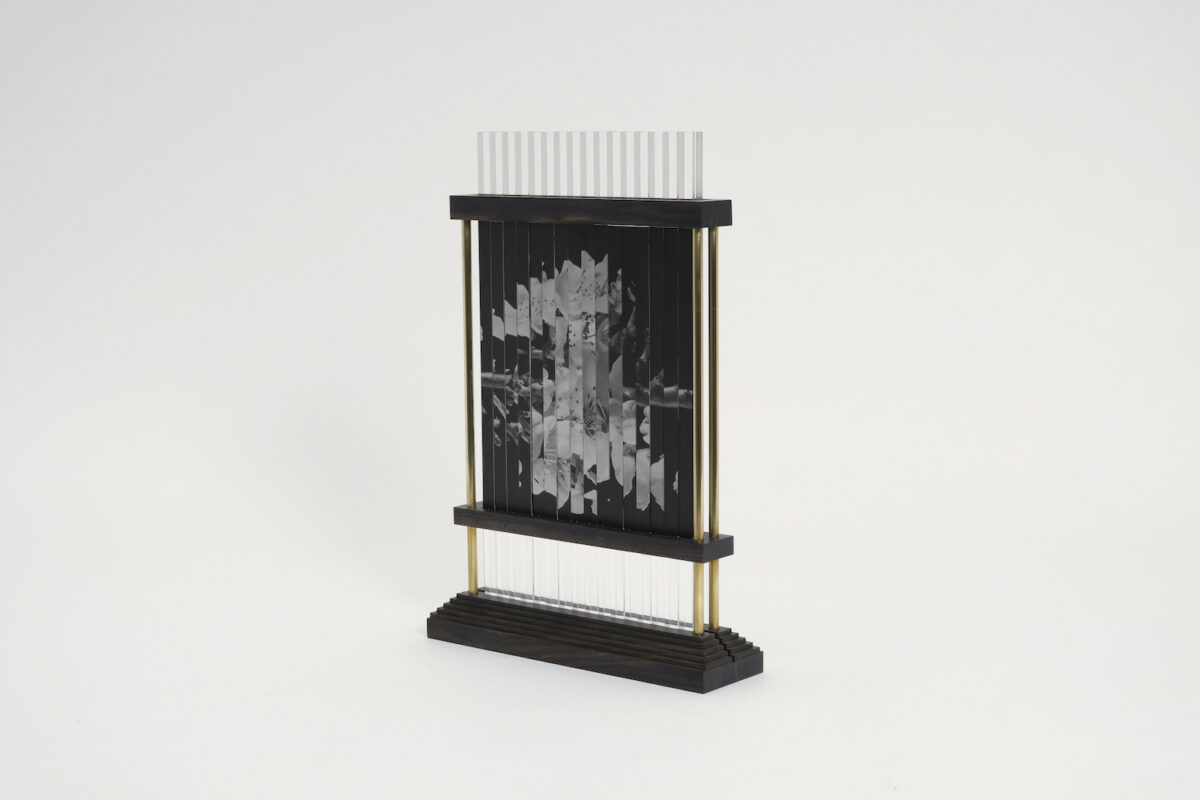

6. Kensuke Koike, Versus

Goliga Editions

Kensuke Koike entrances once again with a series of mind-bending photo-sculptures at Goliga Editions, whose presentation is one of the most mesmerising and unique of the book sector. The brass and ebony-wooden frames of Versus (2022) create a kind of playground for the collagist extraordinaire, housing 16 loose acrylic bars that display four original vintage prints on each of its sides. Sliced and spliced with razor-sharp precision (it had to be so, because he had only one shot), Koike’s hand-made assemblages, despite their obvious Surrealist twist, in the end defy any “ism”. For one can switch, rotate and recombine the puzzles to activate wonderful metamorphoses – from human to floral and back again – thereby giving these once abandoned relics the chance to live a large, albeit mathematically finite, number of other lives. As for the rolling, cloud-shaped slider that glides across the base to animate the image, it might border on the gimmicky, but there’s no denying its amusement and charm. Nothing and everything is left to chance for Koike, who offers us a most pure form of visual pleasure: play.

Paris Photo runs at the Grand Palais Éphémère until 13 November 2022.

—

Alessandro Merola is Assistant Editor at 1000 Words.

Images:

1-Boris Mikhailov, The Theatre of War, Second Act, Time Out (2013). Courtesy the artist and Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve.

2-Boris Mikhailov, Tea, Coffee, Cappuccino (2000–10). Courtesy the artist and Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve.

3-Daido Moriyama, The Artist’s Bedroom (2008). Courtesy the artist and Jean-Kenta Gauthier.

4-Hanako Murakami, The Immaculate #D5 (2019). Courtesy the artist and Jean-Kenta Gauthier.

5-Noémie Goudal, Mountain III (2021). Courtesy the artist and Galerie Les filles du Calvaire.

6-Cannon Bernáldez, El estado normal de las cosas (2022). Courtesy the artist and Patricia Conde Galería.

7-Jean-Vincent Simonet, Door (2022). Courtesy the artist and Sentiment.

8-Jean-Vincent Simonet, Untitled #5 (2022). Courtesy the artist and Sentiment.

9-Kensuke Koike, Versus #12 (2022). Courtesy the artist and Goliga Editions.

10-Kensuke Koike, Versus #17 (2022). Courtesy the artist and Goliga Editions.