Cristina De Middel

Party:(Quotations from Chairman Mao)

Interview with Brad Feuerhelm

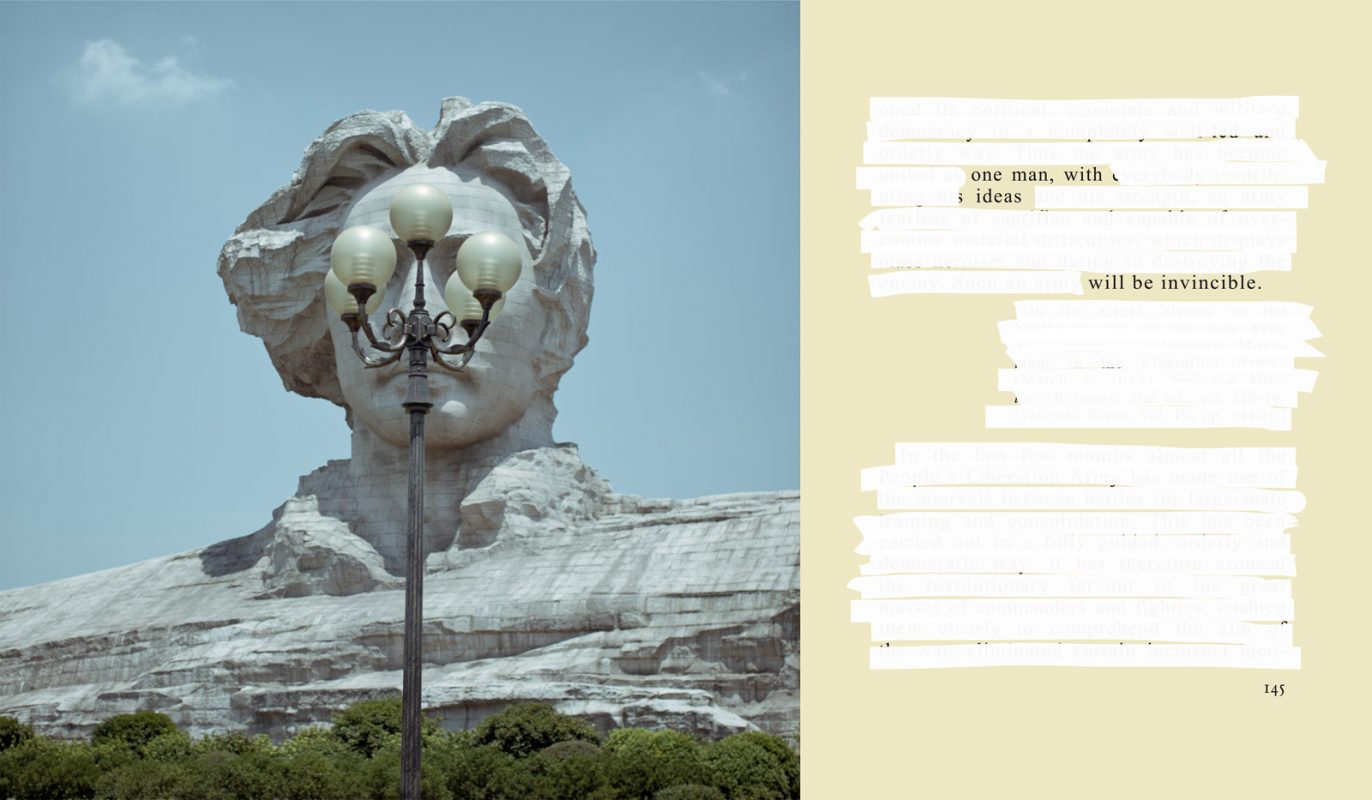

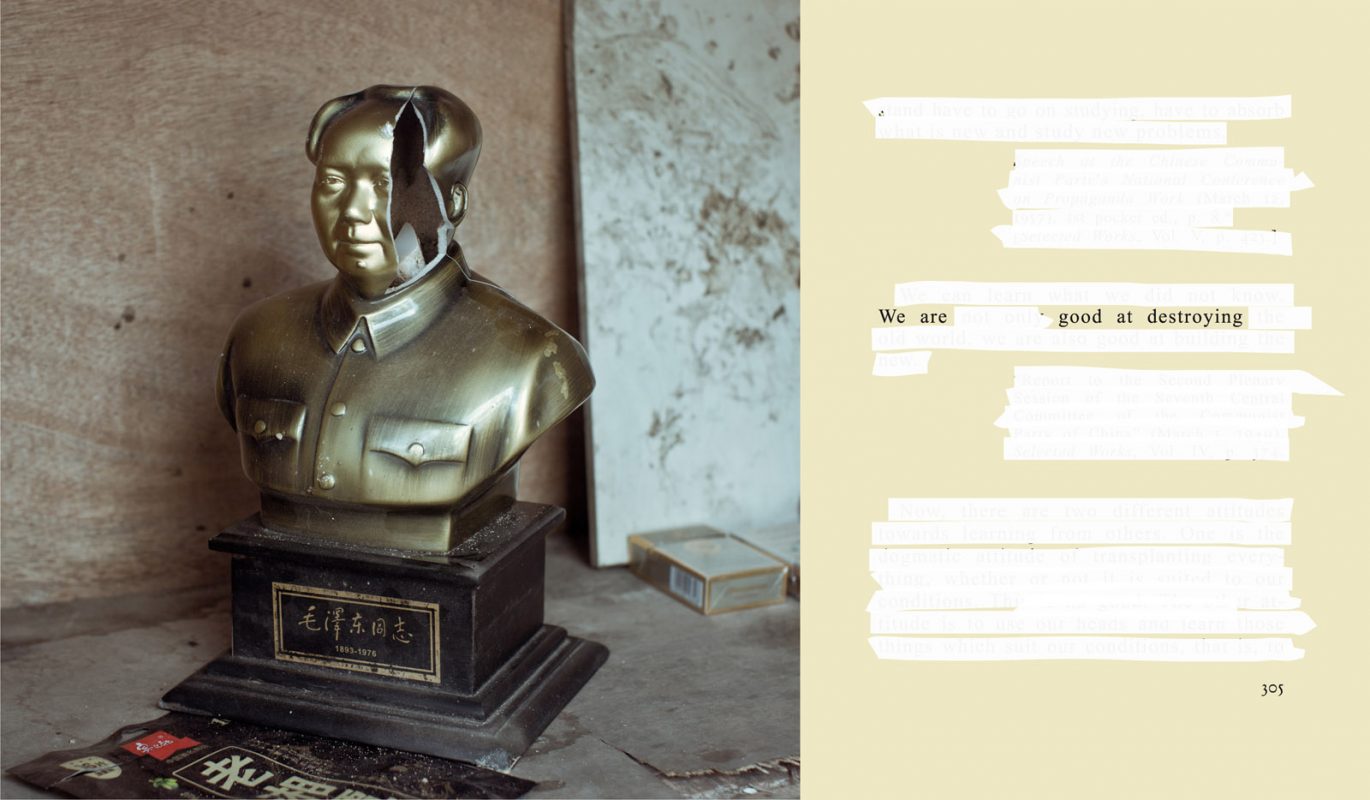

Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, commonly known as the Little Red Book, remains one of the most widely printed books in history. First published by the People’s Liberation Army in 1964, it was a totem facet of every Chinese household during the country’ Cultural Revolution. The book, though not stated as such, was an unspoken Bible of necessity for every party member, printed in small sizes in order that it could easily be carried around and bound in vivid red cover. When issued, it literally changed the shape of publishing in China. Presses for other books by Vladimir Lenin and Friedrich Engels were put on hold, so that Mao’s could be printed and celebrated to marvelous effect by the machine of Chinese communism and the ego affect of the Chairman himself. Economically devising a way to put himself on par with the great thinkers of communism by tyrannical control over the presses, Mao’s spread of influence was capitalised in effect by economic bullying of the Chinese printing industry. A great sense of irony permeates over this.

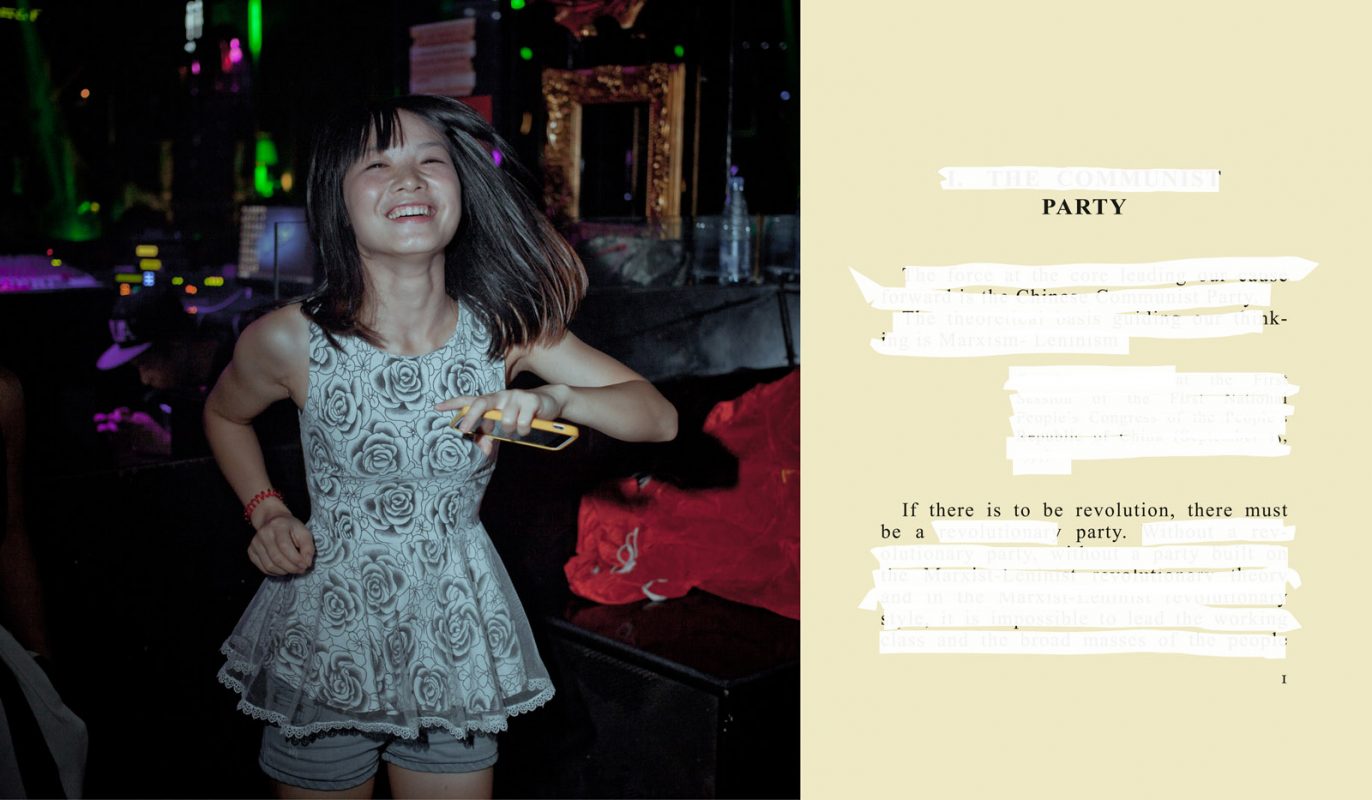

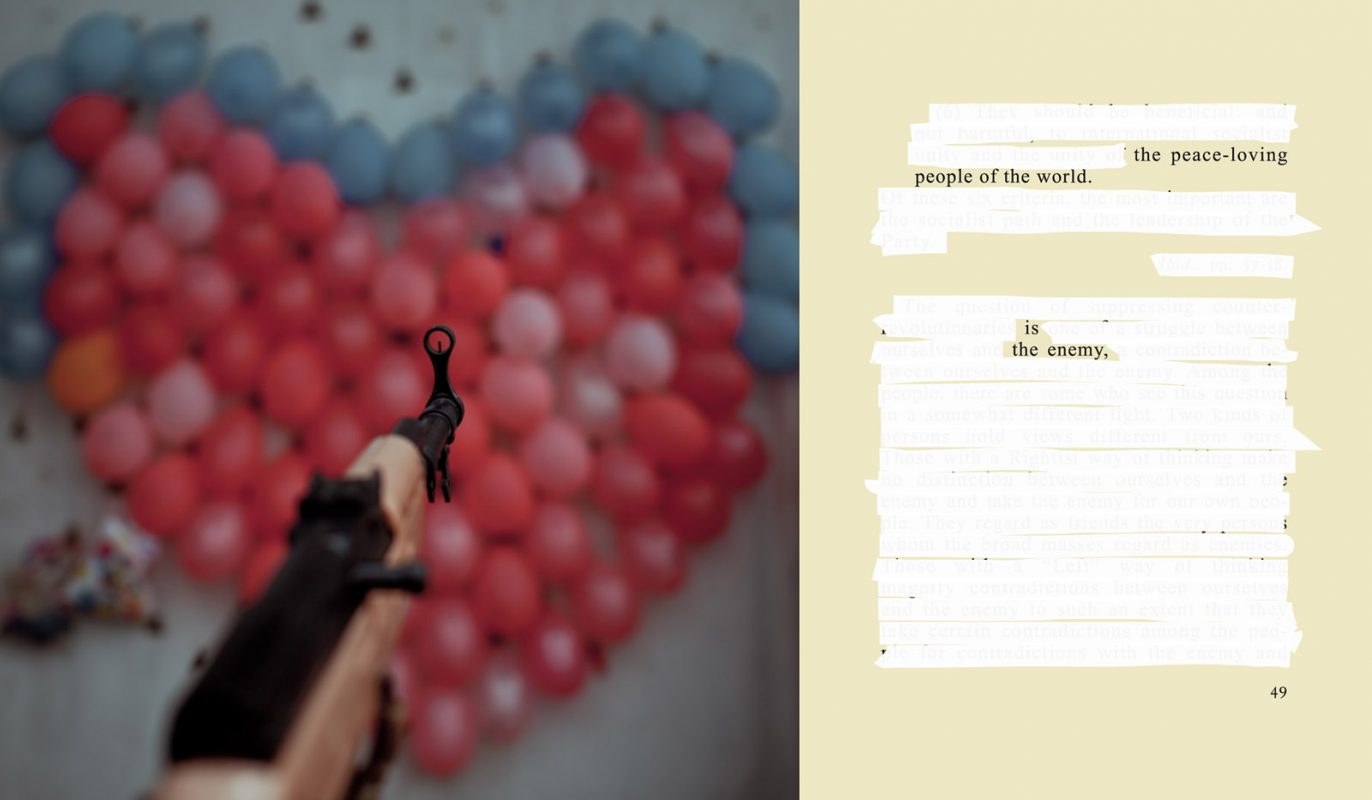

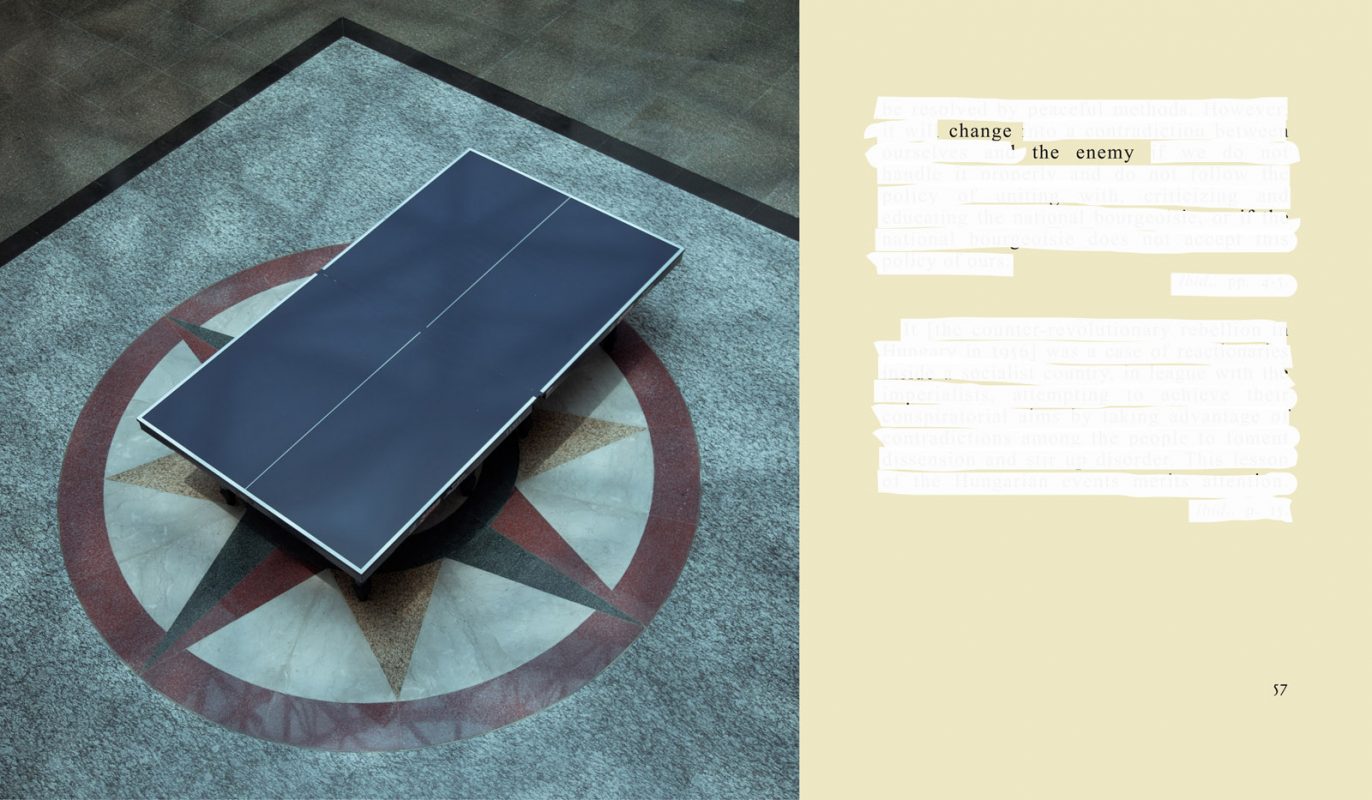

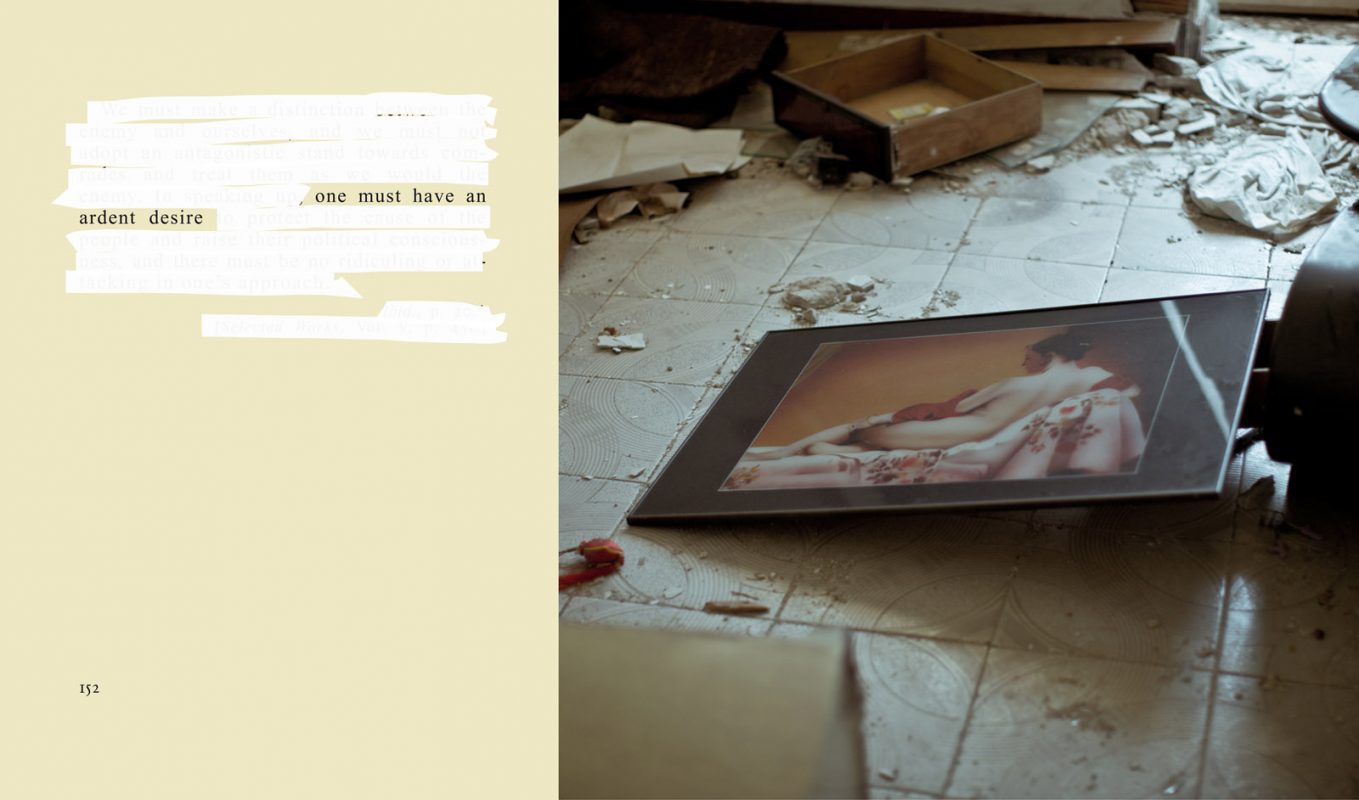

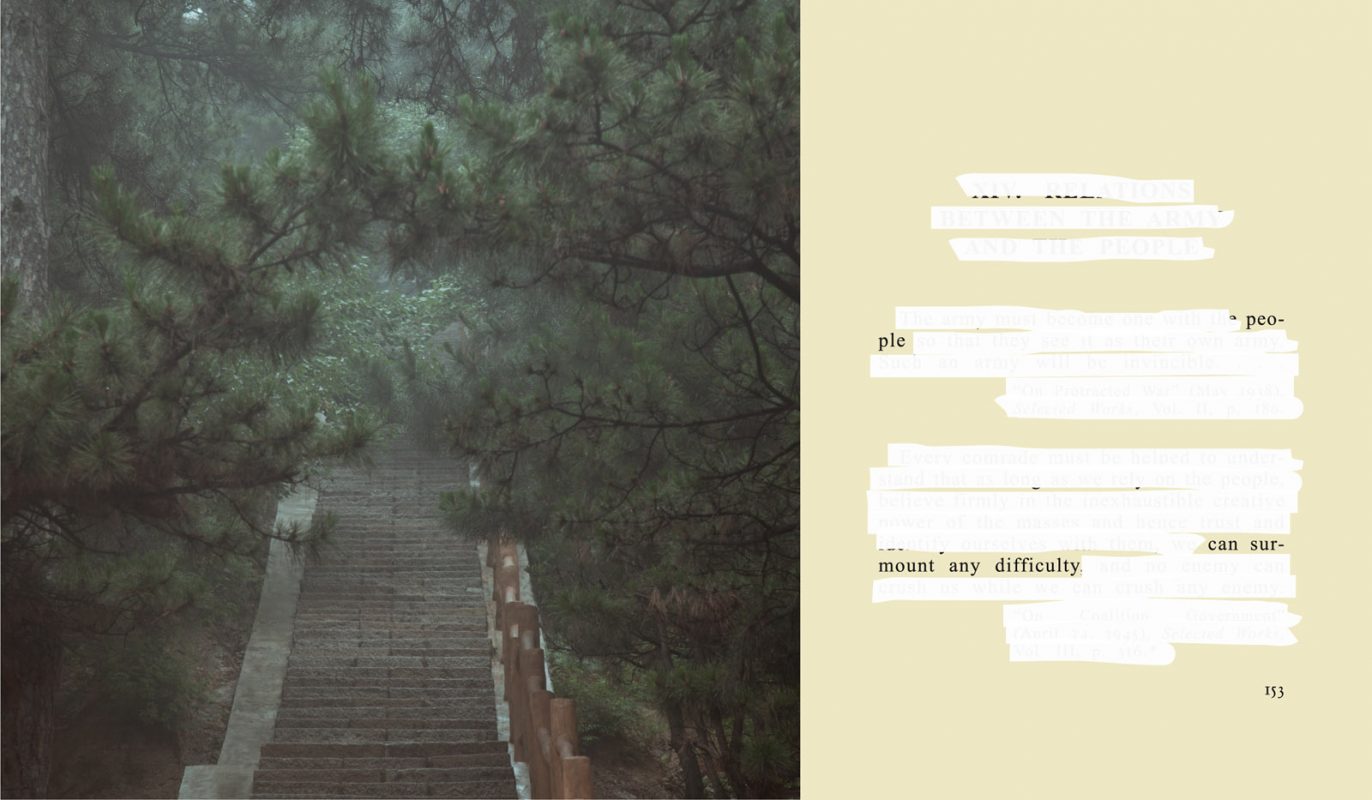

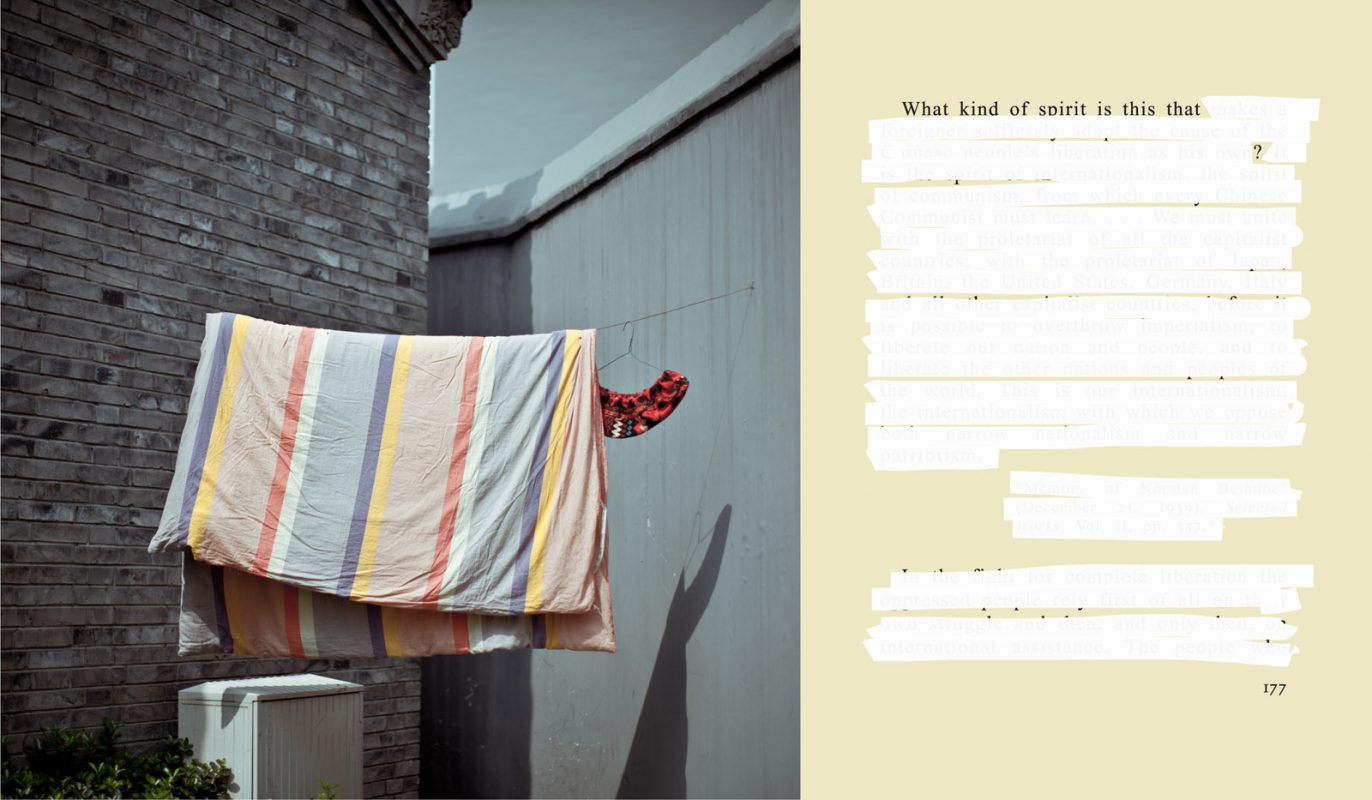

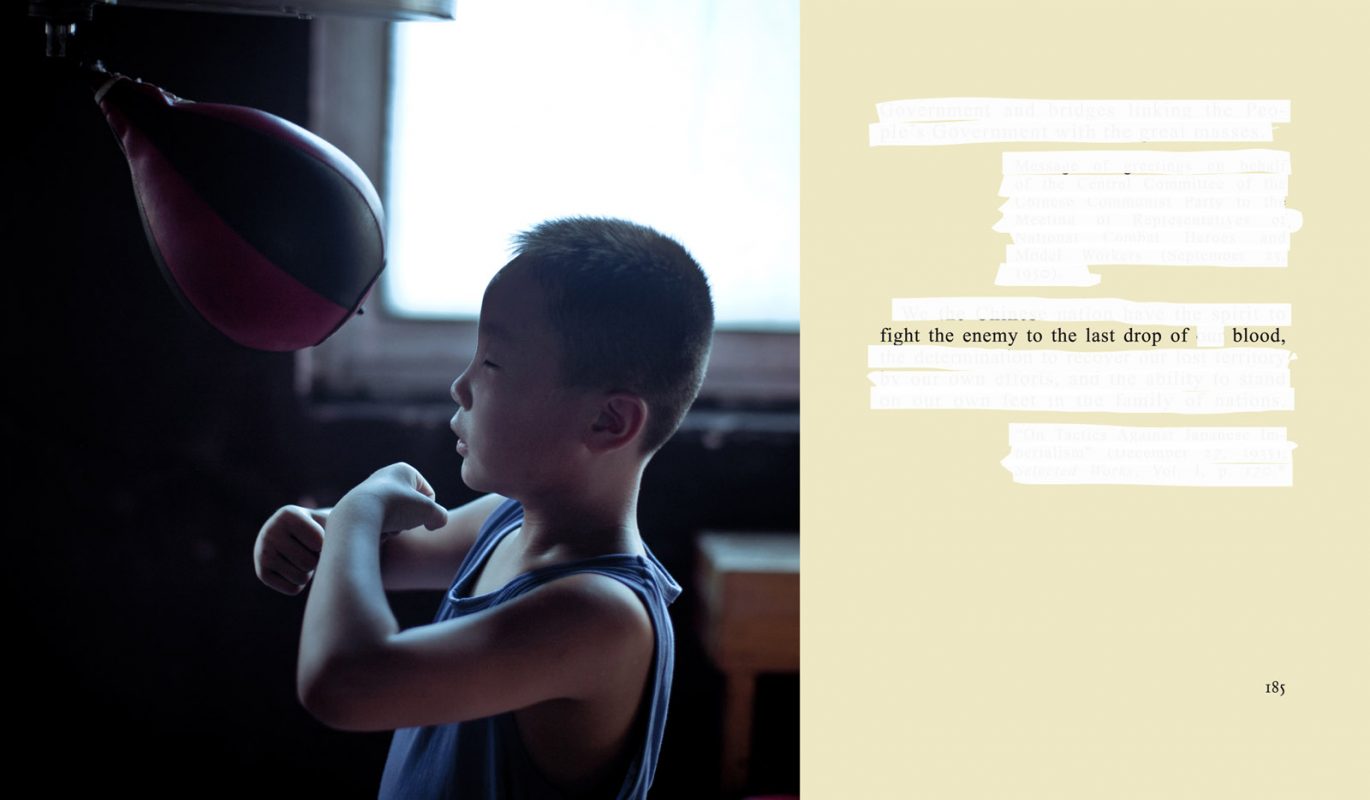

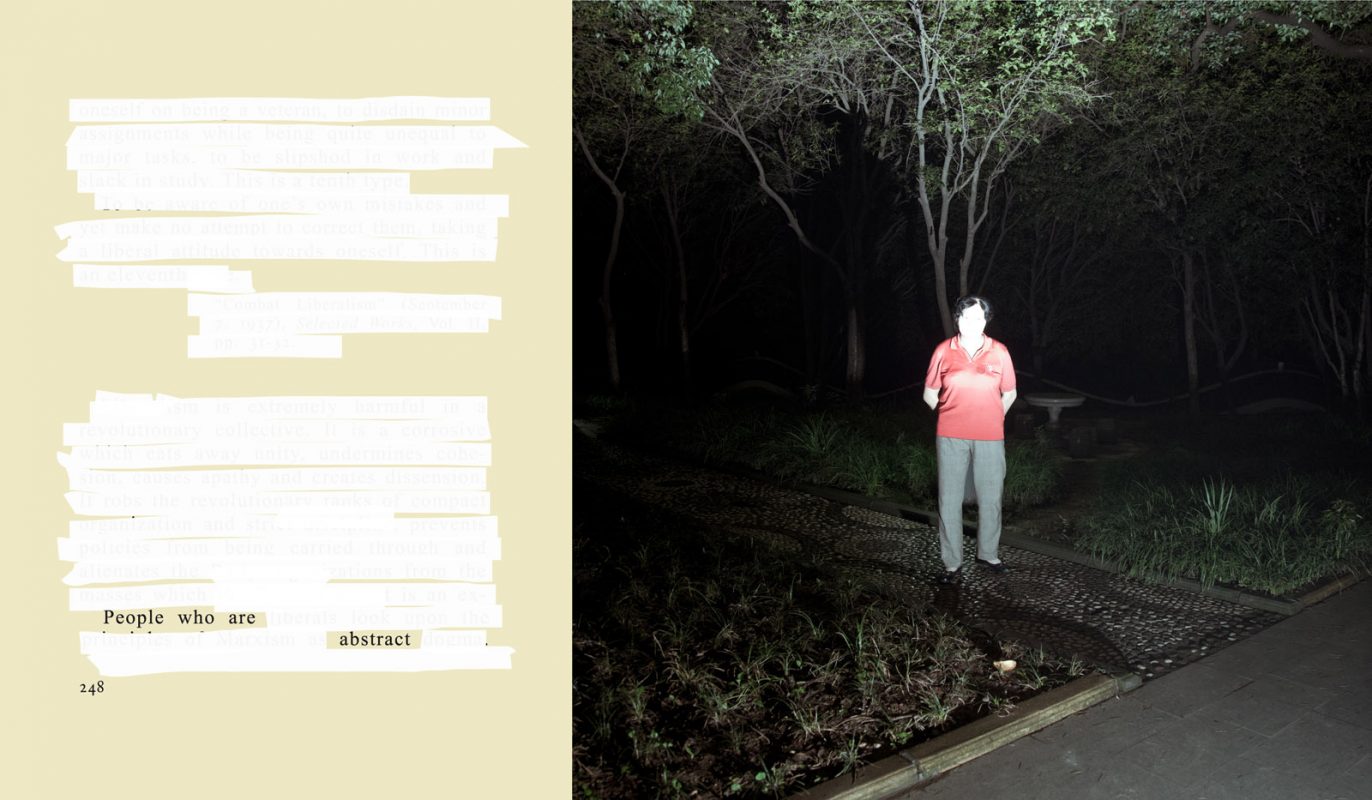

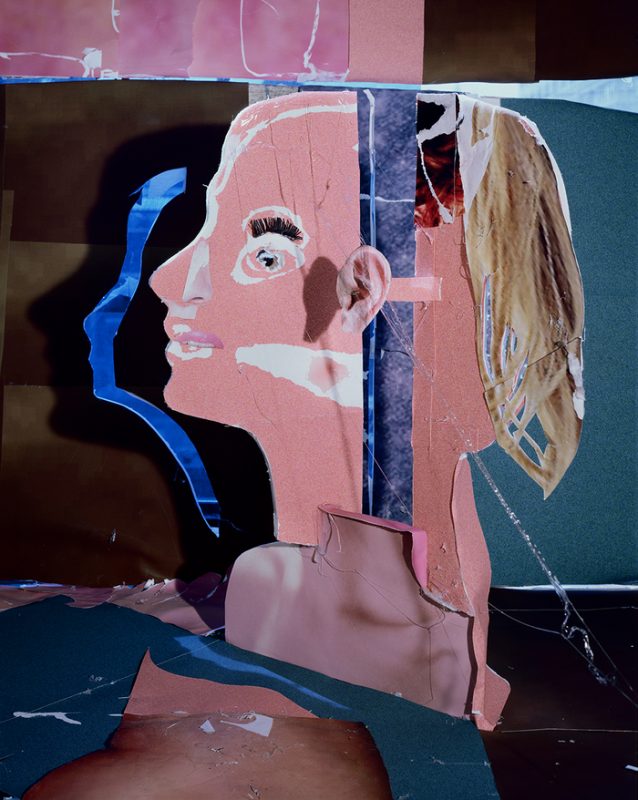

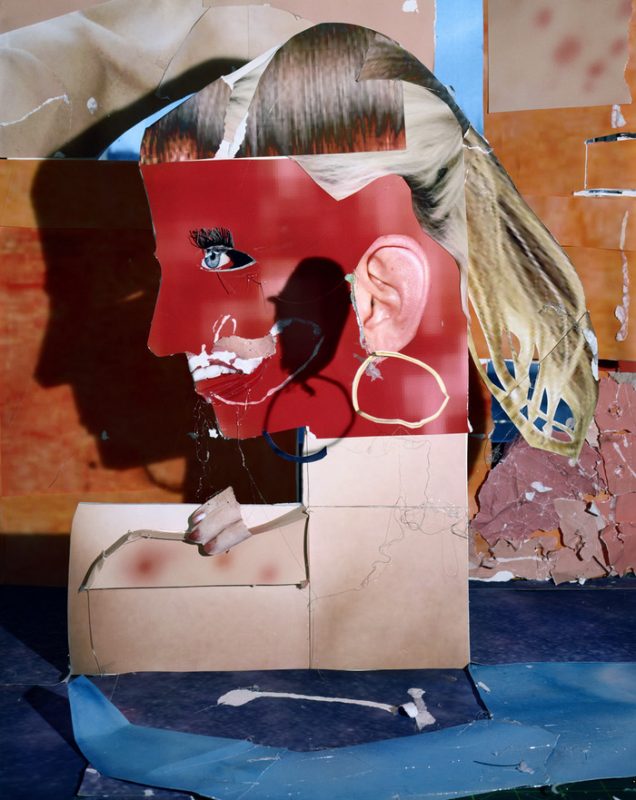

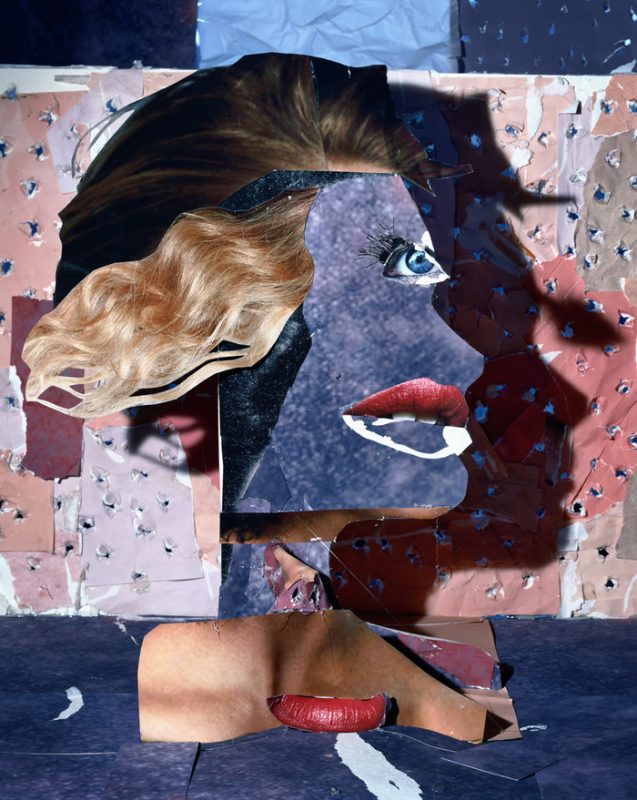

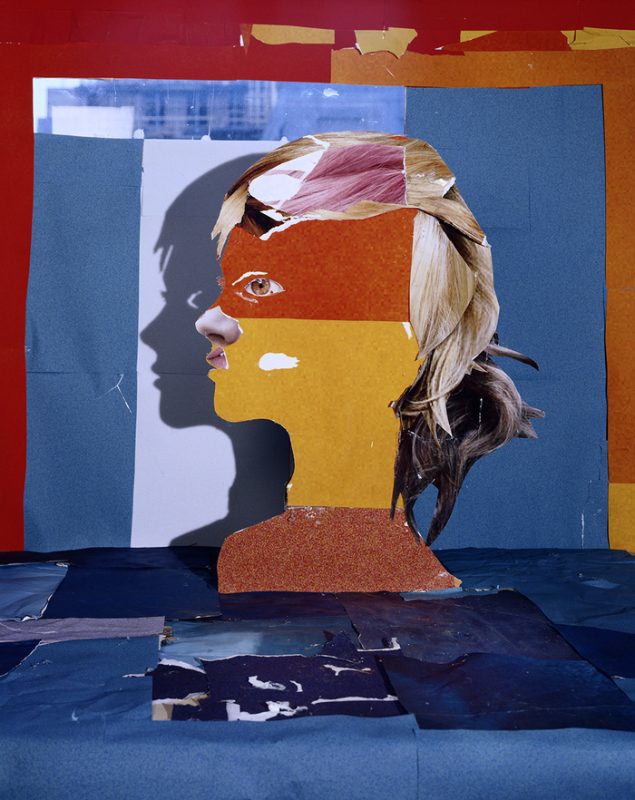

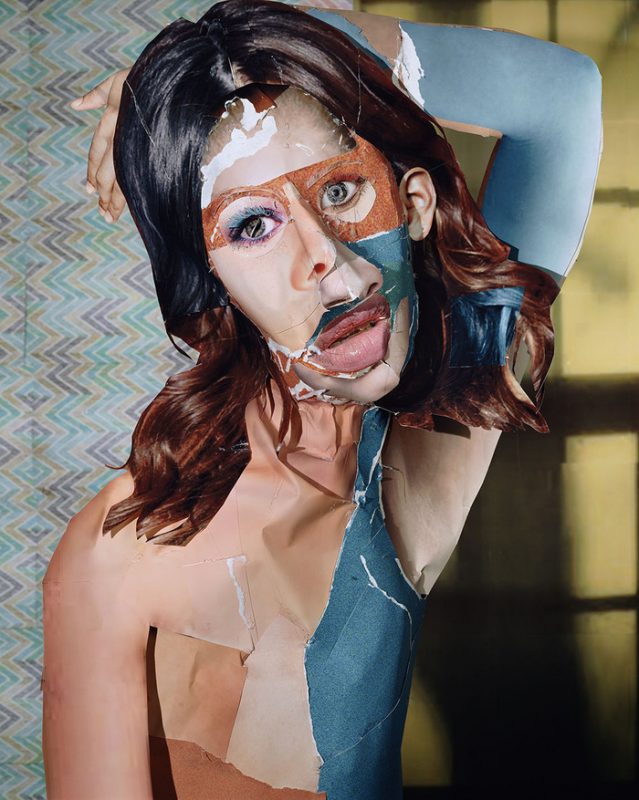

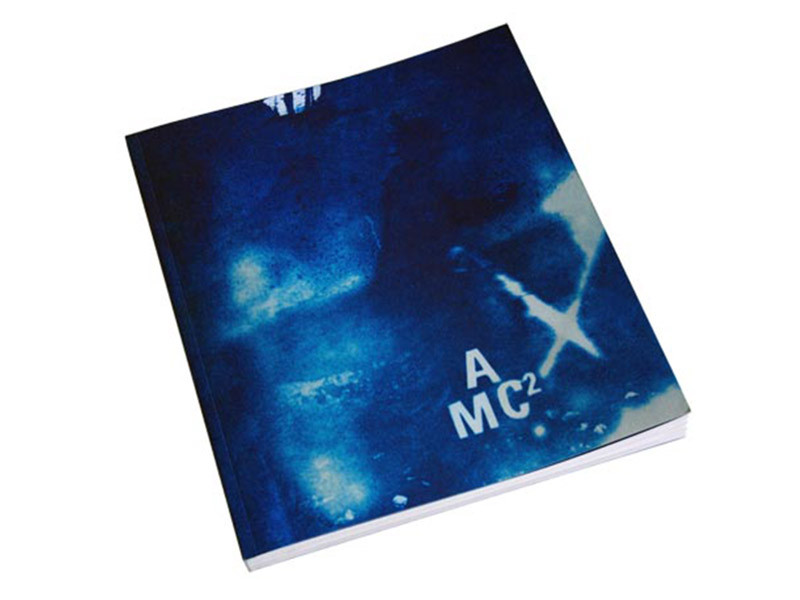

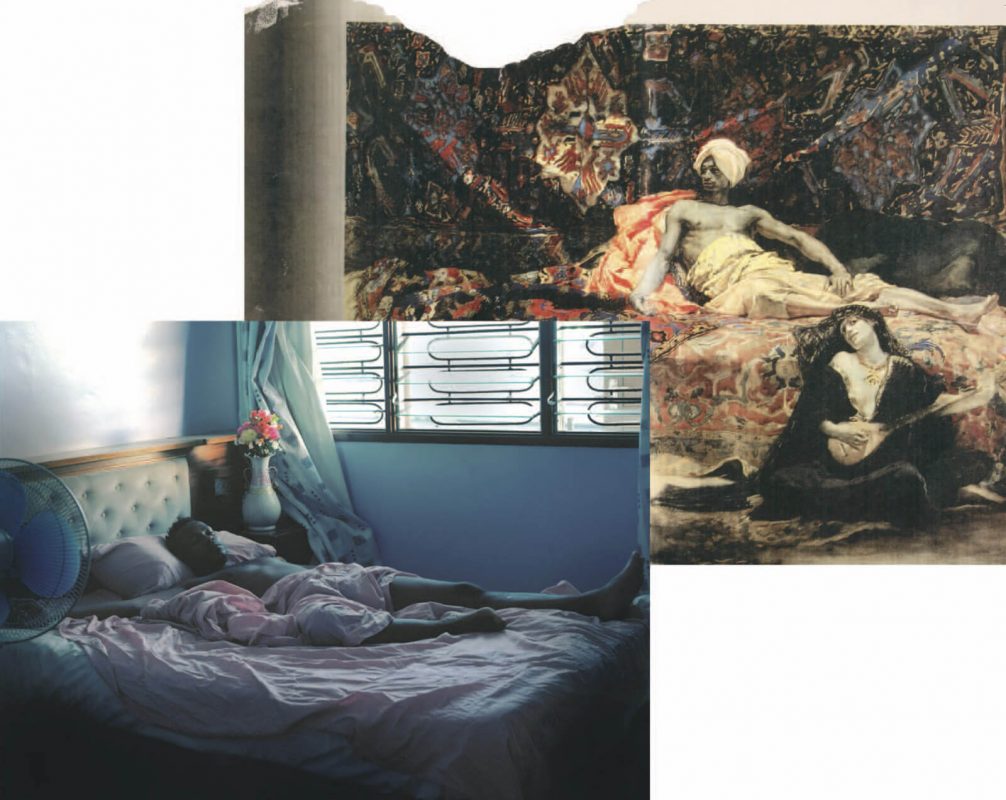

Cristina De Middel, whose The Afronauts marked an unparalleled rise in photobook fetishism has now reworked Mao’s book. She has combined photographs from a recent trip to China with a series of interventions with the original text. Text negation, as seen similarly in the recent Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s Holy Bible has a long history; the conscientious obliteration and reshaping of contextual meaning through absence or striking out of text was a pursuit purloined from the Dadaist tradition and also more singularly by Sicilian artist Emilio Isgrò. Mao’s red book is perhaps the perfect untapped fodder for such treatment given that China is very much undergoing a major transition, both ideologically and economically. The Cultural Revolution is teetering on the brink of capitalist largesse and De Middel’s book points to a series of propositions about this ‘party’ change.

Brad Feuerhelm: Cristina, can you give us some insight on why you felt the Little Red Book was due for re-examination?

Cristina De Middel: I didn’t start with the Mao book from the beginning. I just used the Mao book as a structure for the pictures I had taken. It was the structure I was missing. The images were quite random. It was not for a specific project.

BF: Do you feel that the original book itself holds any truths about the China of today or is it in any way a sacred cow of literature and ideology in need of some abuse?

CDM: I don’t think it is any of these things. For me it is a historical object, a testimony of something that has happened in the past. It has no literary value. It is simply an ideology put together – it’s just like the Bible. It is full of information, full of perspectives that are of no use anymore.

BF: When I look at the choices you have made regarding the text negation, I feel a certain amount of dysphoria involved. The words ‘struggle’, ‘people act blindly’, ‘oppression’, ‘negate universal truth’, and simply ‘why’ point to series of propositions regarding the measure of failure of communist philosophy for that of a sort despondent embrace of capital in the country. Is this an intentional measure or have we taken it upon ourselves to load such an already loaded tract with obsequious negativity?

CDM: The edit of the text is very intentional. It is meant to transmit my mood at the time. It is closer to a personal diary, using China as a failure for utopia. It was also about the moments I was going through there while shooting.

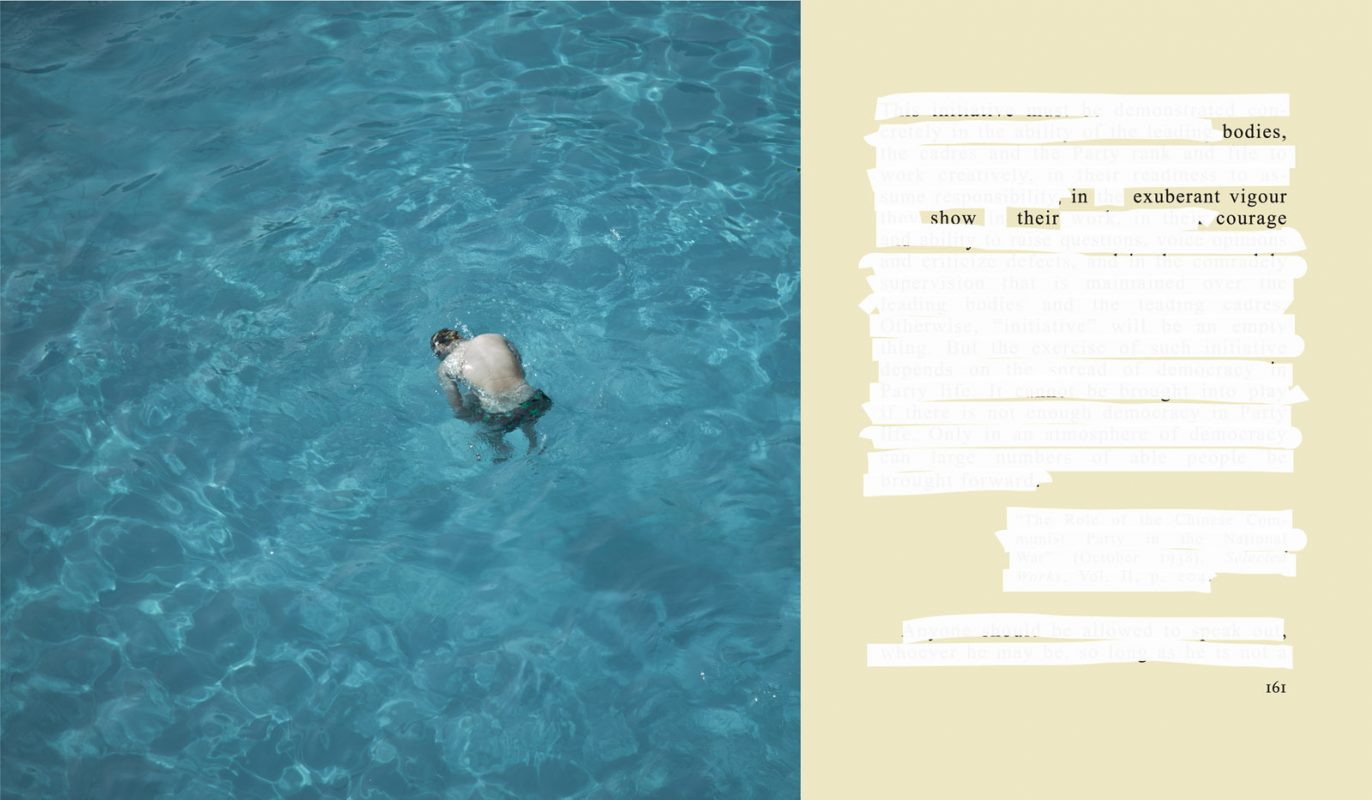

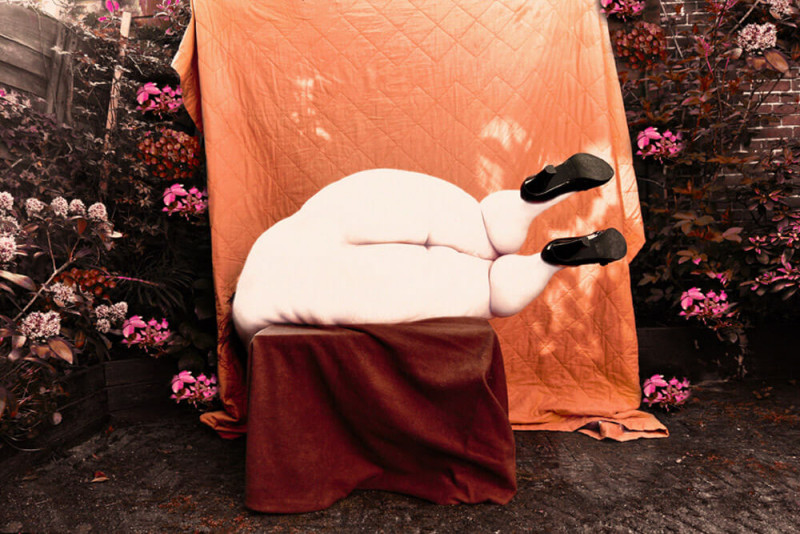

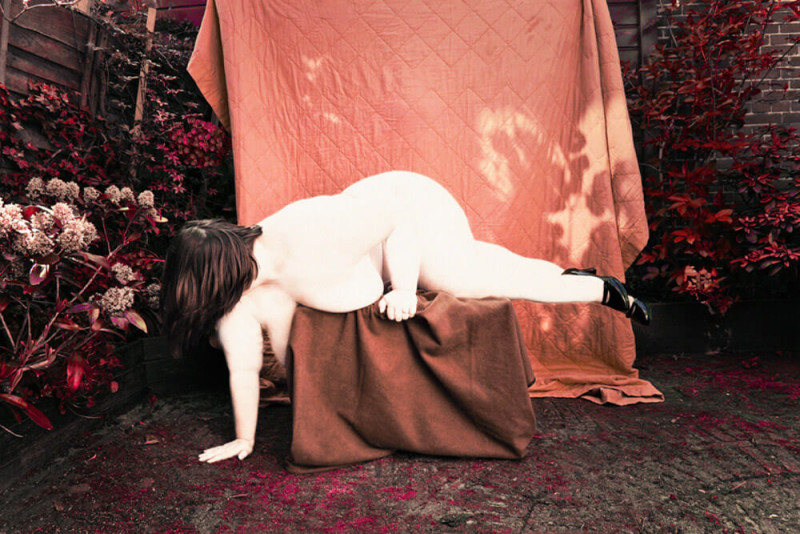

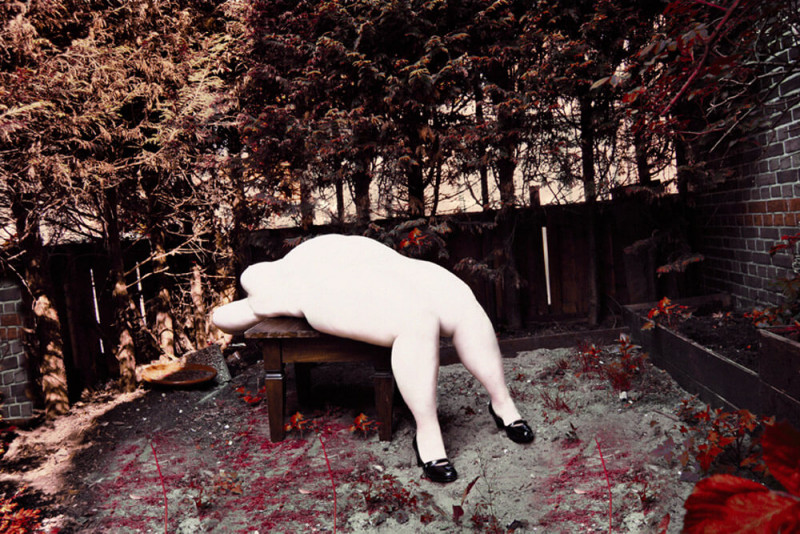

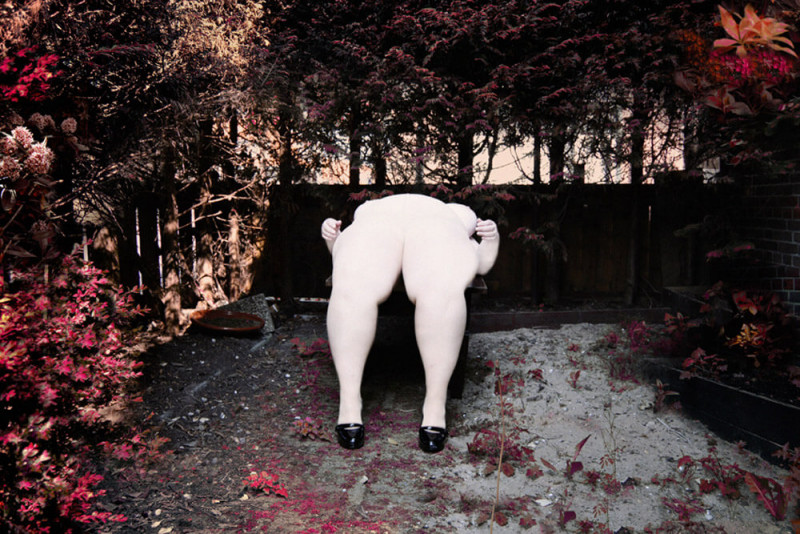

BF: The photographs themselves align quite cleverly with some of the text whether representational images of hands or people pictured in scenarios where they are partying. Did you add the photographs to the text or vice versa?

CDM: I had a lot of the images as a result of spending three months in China during the time I was working on The Afronauts, and I wasn’t sure what to do with them all. I needed to find a structure for this. The failed utopia was a perfect structure – turning a political statement into a personal diary and vice versa. It is the most personal work I have done to date because it may be well hidden, but the book reflects myself very much so at the time – my outlook. I was in a very personal crisis. I had quit my job. I had personal issues, so I went to China to reset myself. I was taken with the idea of rediscovering the pleasure of photography, taking pictures on the street, but also adding a personal perspective of the images.

BF: The images themselves are quite different to those of The Afronauts, where the fictive elements of storytelling and documentary practice cross boundaries to present a fairytale synthesis of unreality. This presumably hints at the fallacy of representation in photographic practice. In part, the images seem to have a more literal, less fantastical shape to them given your prior career as a photojournalist. Was this employment of more traditional, let’s say, more static image selection done on purpose or was it the sequence of events in China itself that led to the making of images? They feel less staged than the images in The Afronauts….

CDM: I am more known now for my fictional stance to photography and documentary practice. That being said, it is more of a transition as I was going through The Afronauts at the time so it wasn’t cemented in what my work is associated with now. I finished The Afronauts in December 2011, whereas this was actually shot in August of the same year so it is also sort of research on how to use a book as a documentary object and how to use the historical weight of the culture and book to say what you want to say. As the critic and curator, Aaron Schuman has pointed out about my work in the past, it is like a system of failure and utopia. It is the same with The Afronauts. It is about failure but when I was working on the series I had no need to play with fiction. I was dealing with my own reality and the hard reality of the culture, there was little need to stage that further. Also, I didn’t even know I was going to do a book – it was more photographic therapy having being disappointed with photojournalism. I was focused more on my feelings and opinion of the place rather than the staging of an idea.

BF: Would you say that, by and large, photography is about failure or just your perspective of playing up to it through story telling?

CDM: Photography is not about failure per se. Actually, I think it is one of the best tools you can use for storytelling. It is about success. It is more the promise of utopia and people’s expectations or idea of reality, places and things that is exposed to failure. At some point there is success through communication. Failure is about expectations. Photography is maybe the tool for me to treat that disappointment because if the latter comes from when reality is not what you expect it to be, with photography you can control that. It is a medicine to cure disappointment.

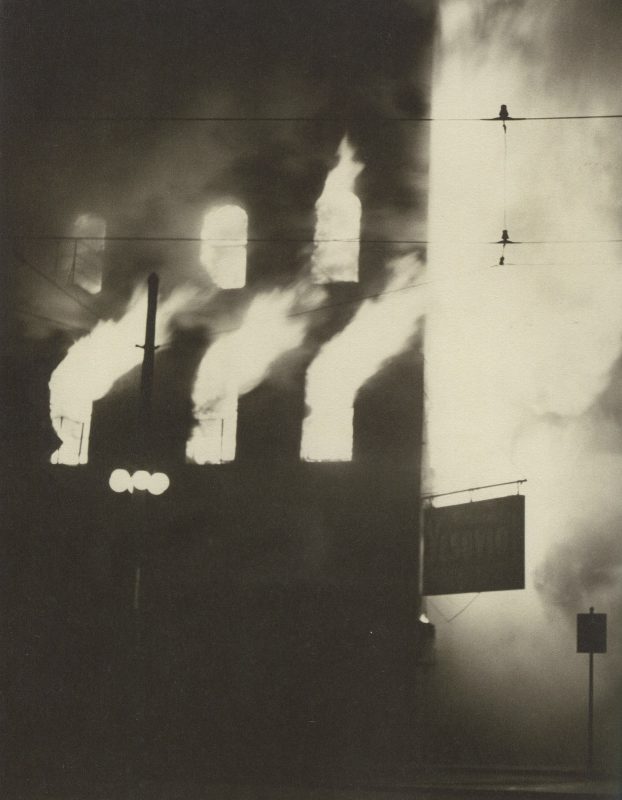

BF: On page sixty-four, there is an image of a man who looks a lot like the Chairman himself bathed in a sort of strawberry pink light. Was this an intentional use of a doppelganger? If so, what process was there to find someone that carried these traits while in China?

CDM: No, I found him by chance. It is not staged at all. The guy looked like Mao. The light is a long distance rifle light from an exhibition, which suggests feelings of threat by the government, the struggles and impressions of a threatening government but also personally how one can feel like a target – pointed at by everybody.

BF: Do you feel China is going through another Cultural Revolution or perhaps a revolution of complicity in contradiction to its status of economic revolution?

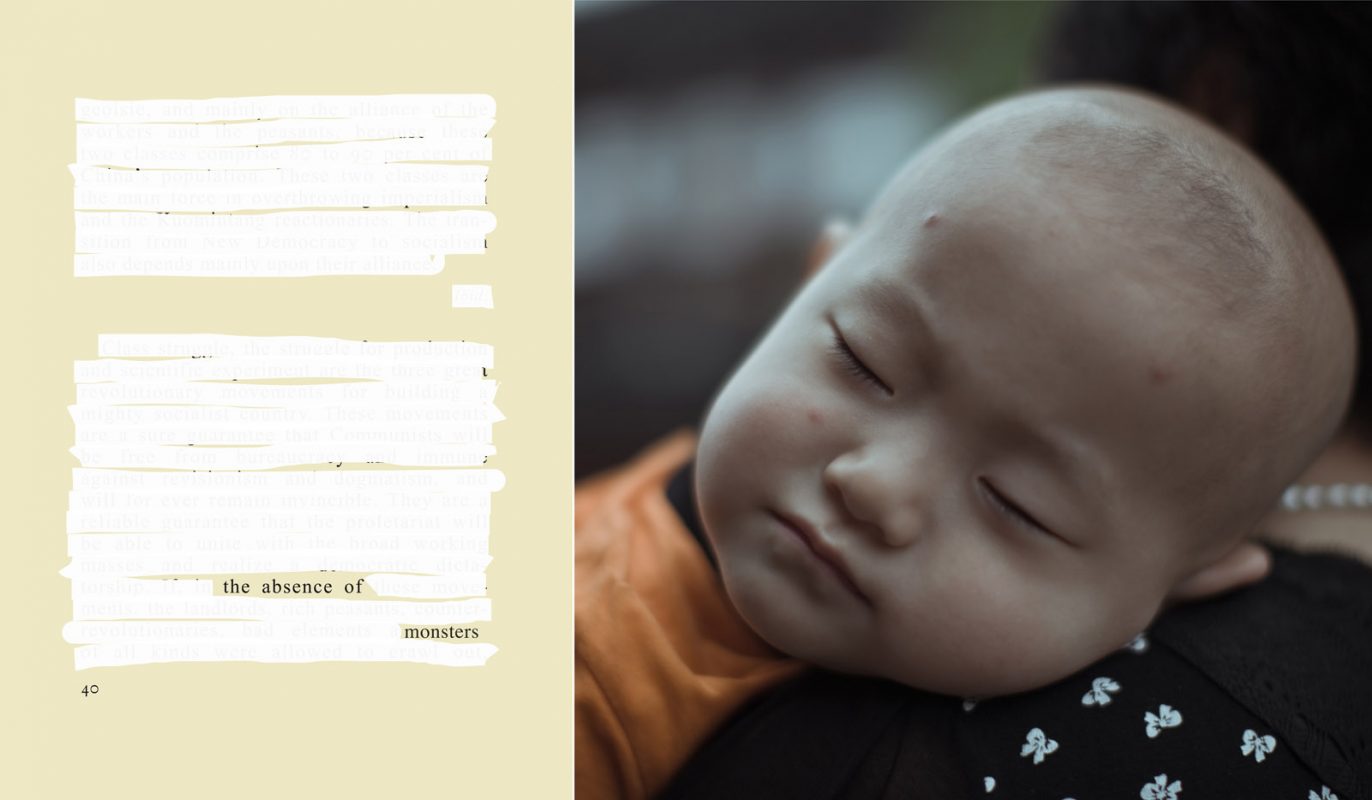

CDM: From what I saw, my own personal experience, I don’t think their revolution is something new since they are repeating mistakes that perhaps the West is trying to fix now – principally the endorsement of capitalism amidst a tyrannical regime. It is hard to have hope. It is like a timebomb, especially the results of the infamous One Child Policy. If we all agree that by 2016 they will be the strongest economic power, who will be ruling their country? They don’t know how to share; they raised as one child with lots of pressure, both academic and economic. Imagine the perspective of these people ruling one massive country – little empathy and no charity. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Cristina De Middel

—

Brad Feuerhelm is a London based, American collector and dealer in vernacular photography. He is also managing editor at American Suburb X.