Bryan Schutmaat

Good Goddamn

Book review by Gerry Badger

I think I am beginning to see a trend amongst a certain group of American photographers, not exactly a runaway trend but at least a tendency. I thought this when I saw Tim Carpenter’s book, Local Objects, which was deservedly praised by John Gossage and also Ron Jude, who is himself part of this tendency, while Gossage is one of its big inspirations. Carpenter’s book was small, shot in black-and-white, restrained in design, and concentrated upon the photography. And crucially, it dealt with non-metropolitan America, the huge heartlands of the country that are so different, and almost diametrically opposed to the coastal conurbations.

Photographers like Ron Jude, Christian Patterson, Gregory Halpern, Raymond Meeks and others, most of them originally from the heartlands themselves, have been examining America’s interior myths and realities for a number of years, and can be said to constitute the latest generation of photographers, beginning with of course Walker Evans, who have gone in search of – as the French might put it – America profond.

Bryan Schutmaat first came to the photo-world’s attention with a classic of the genre. His Grays the Mountain Sends (2014) was a superb book, a series of portraits and landscapes of small, almost forgotten communities in the Rocky Mountains. It was a lavish, superbly produced book, shot in sumptuous colour, which demonstrated that Schutmaat was not simply a photographer of rare ability – especially in his haunting portraits – but someone who could use photography effectively to build a narrative.

That is the point about Schutmmat and what someone has called – whether kindly or unkindly I’m not sure – the ‘lumberjack’ school of photography. John Gossage recently said that he took up photography because it “allowed me to understand things that were not spoken.” Looking around a lot of today’s photography, it would seem that its makers are suspicious of this dictum, and are distrustful of photography without the crutch of words – or overelaborate design, which can amount to the same thing.

Not so Ron Jude, or Tim Carpenter, or Bryan Schutmaat. Grays the Mountain Sends did not suffer from a surfeit of words, and neither does Good Goddamn, which is modest in size but displays both an assuredness and a quiet ambition. Interestingly, Schutmaat has switched to black and white for this project, which seems to be making a claim for the work’s seriousness. Similarly, the restrained, classical design, like that of many American photobooks, states a certain respect for the integrity of the photographs themselves.

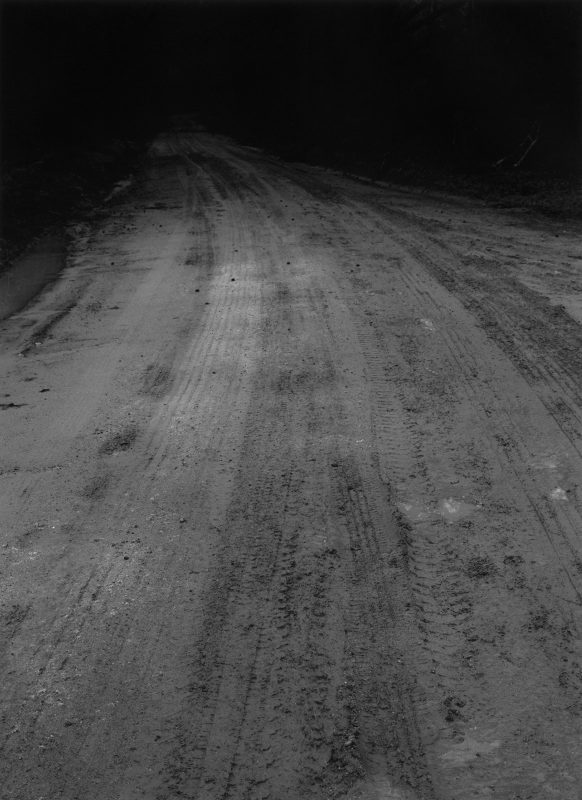

Good Goddamn, published by Trespasser, tells a nominally simple story. Shot over a period of a few days in February 2017, in Leon County, Texas, Good Goddamn documents, in only twenty-seven photographs, the last few days of freedom of Schutmaat’s friend Kris before he went into prison. As this is a book of hints and half-lights, the spaces between the pictures being as important, so to speak, as the pictures themselves, we are not informed of the crime that led to Kris’s incarceration, nor the duration of the sentence. But the fact he was not in custody possibly suggests that the misdemeanour was not serious, although the psychological weight of the book perhaps points to the opposite.

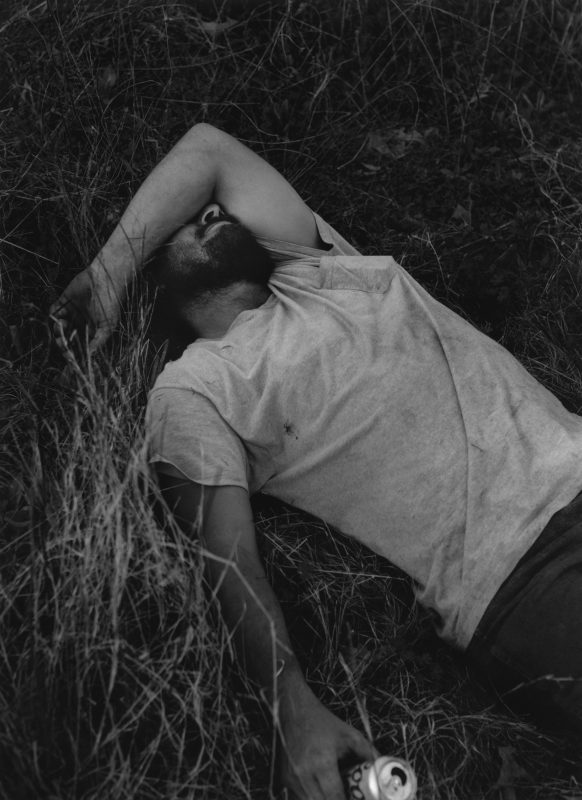

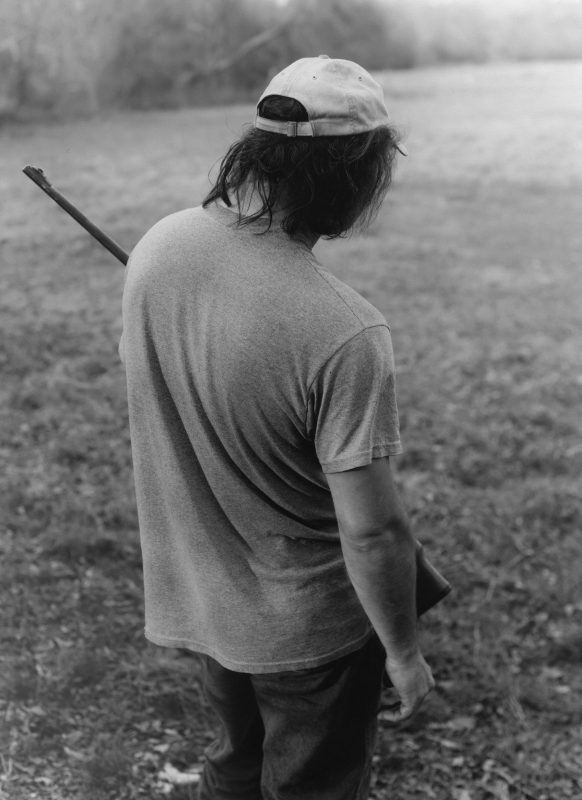

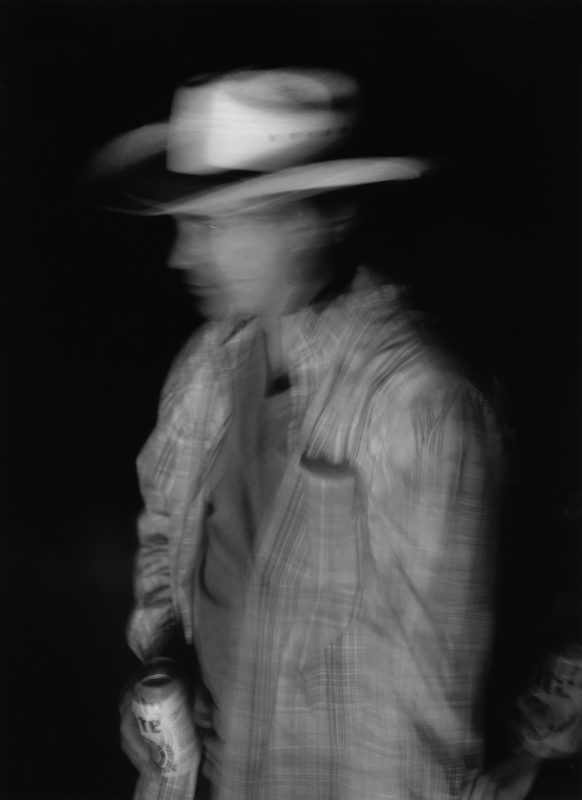

The cast of characters, besides Kris himself and the bleak mid-winter Texan landscape, are an old pickup truck and a hunting rifle with a very business-like telescopic sight. And there is an enigmatic blurred figure in two images at the end who might be Bryan Schutmaat, or a deputy sheriff come to escort Kris to his fate. Kris’ final days of freedom seem to be spent drinking Coors Lite or shooting his gun. So far this is a typically male Texan as we imagine them, tough guys who never cry, but the macho surface image is thoroughly undercut by the book’s elegiac tone and complex emotional mood. There is a general aura of wistfulness, not to say sadness, but also encompassing moments of reflection, uncertainty, loneliness, and bitter reflection, making for a concerto of shifting emotions in which the bare, gloomy landscape pulls the strings. The constant background is the expectation that what will follow will be a life changing experience for Kris, and not, at least in the short term, a good one.

All this is suggested by Schutmaat’s exceedingly well judged photographs – the somewhat indeterminate portraits of Kris drinking, smoking, or cradling his rifle, in nagging juxtaposition with the bleak but beautiful February landscape. One can almost feel the damp. Yet even a bleak, damp landscape will be a great loss when you are behind bars. I call the portraits indeterminate, not because they are soft in focus, but because they have an unsettling quality, which may come from nothing more than the sight of Kris in a short-sleeved tee shirt in a winter landscape – even though we are told that the weather was unseasonably warm during the shoot. Of course, it is more than that, Schutmaat has conveyed the psychology of this moment in Kris’ life unerringly, and makes us feel it too. Little wonder we are disturbed and unsettled.

In the end, Good Goddamn is about the photographs, which is not always the case with photobooks. As he demonstrated in Grays the Mountain Sends, Bryan Schutammt is a photographer with a rare sensibility, the pictures in Good Goddamn are so finely calculated and balanced. I can only compare his talent to that of a superior musician. There are many calling themselves ‘musicians’, but the difference between an ordinary musician and a great one is vast, and yet tiny – a matter of subtlety, the right emphasis, and nuance. It is like this with Schutmaat’s photographs. His images sing, like a well-played piece of music. They are a pleasure to contemplate, and contemplate over and over again for their felicities. They lend the book its visual delights, but also its emotional depths and bitter-sweet tone.

As always in photography, they are pictures of things we have seen before, many times. Ordinary but important things. Yet in themselves they are new, pictures we have not seen before. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist and Trespasser. © Bryan Schutmaat

—

Gerry Badger is a photographer, architect and photography critic of more than 40 years. His published books include Collecting Photography (2003) and monographs on John Gossage and Stephen Shore, as well as Phaidon’s 55s on Chris Killip (2001) and Eugene Atget (2001). In 2007 he published The Genius of Photography, the book of the BBC television series of the same name, and in 2010 The Pleasures of Good Photographs, an anthology of essays that was awarded the 2011 Infinity Writers’ Award from the International Center of Photography, New York. He also co-authored The Photobook: A History, Vol I, II and III with Martin Parr.