A tribute to Brian Griffin (1948-2024)

Leading figures from the UK photography community – including Photoworks Director, Louise Fedotov-Clements, and founder of the Centre for British Photography, James Hyman – remember Brian Griffin, who died 27 January 2024 at the age of 75.

Louise Fedotov-Clements, David Moore, James Hyman, Peter Bonnell, Ravi Chandarana, Graeme Oxby | Obituary | 8 Feb 2024

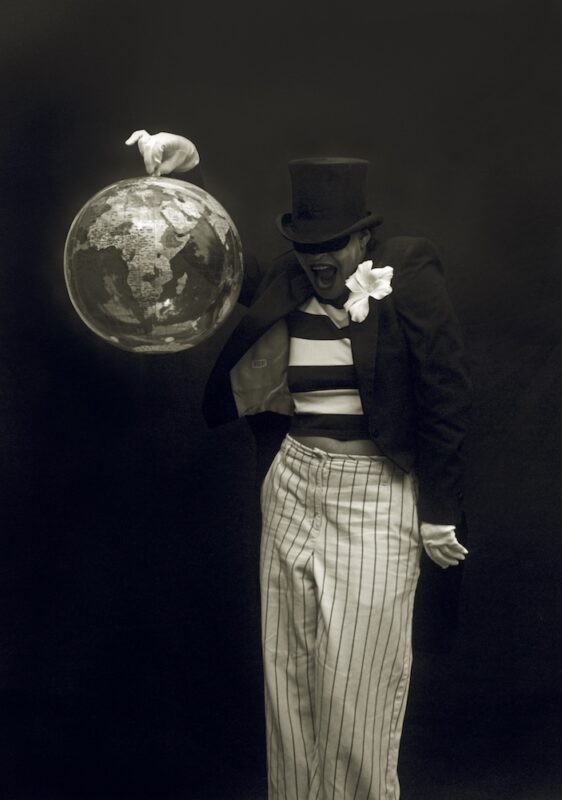

Widely acknowledged as one of the most prominent photographers of his generation, Griffin was born in Birmingham and left school at 16 to work as trainee pipework engineering estimator for British Steel before going on to study at Manchester Polytechnic where he met Martin Parr. Moving to London, he started out as a freelance photographer in 1972 and was first commissioned by Roland Schenk, shooting playfully subversive black and white portraits for business magazine Management Today. His inspirations ran the gamut from Renaissance painting to Surrealism and German expressionist cinema. Golden years in the music industry saw him produce countless iconic album covers for Depeche Mode, Iggy Pop and Kate Bush, and others, alongside work for various design and advertising agencies.

Constantly pushing at the boundaries of artistic and corporate photography, the Guardian named him as the ‘photographer of the decade in 1989’. Seminal exhibitions at The Hayward Gallery, London, and Les Rencontres d’Arles, curated by Paul Hill and François Hébel respectively, brought international attention. Griffin subsequently produced over 20 photobooks and was the subject of more than 50 exhibitions across his career. His work is held in collections at Victoria and Albert Museum, London; National Portrait Gallery, London; Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery; Reykjavík Art Museum, Iceland; Mast Foundation, Bologna; Museum Folkwang, Essen; and the Museu da Imagem, Braga, Portugal. In 2009, Brian Griffin became the patron of FORMAT Festival and in 2013 he received the Centenary Medal from the Royal Photographic Society in recognition of a lifetime achievement in photography.

Brian was a very dear friend and colleague. He will be deeply missed as a member of the photography family. Our thoughts are with all who loved him. The memory of his wonderful, playful and surreal energy, curious mind and generous spirit will forever be a source of inspiration. He was one of the most influential and subversive photographers of our time. I had the pleasure of working with Brian as he became FORMAT Patron after we met at our first edition in 2005, since then we collaborated on many editions of FORMAT including commissions, films, events and exhibitions in Derby, the UK and internationally.

Always critical and unique in his avant-garde approach to photography, no matter what context he worked within – from business men to construction workers, musicians to aristocracy, the street to still life – Brian sculpted light and composed his images in his own recognisable innovative style. His knowledge of, and passion for, photography and photographers was unending. He was always enthusiastic to support new talents and never slowed down with his own ideas and future plans. Brian was truly one of a kind, a legendary image-maker and genuine artist. His memory and influence lives on.

Louise Fedotov-Clements

–

The first time I knew of Brian, without knowing who Brian Griffin was, was through my dad’s subscription to Management Today magazine during the mid to late 1970s. Looking through the magazine and finding Brian’s extraordinary, and at that time, bewildering images, I had no idea that I was witnessing a truly innovative and influential collaboration that was to significantly shape a particular history of British photography located between art and commerce.

Over the last 15-20 years we became good friends. I was always “young David” of course. We had conversations about photography and life, and occasionally ageing. “I look at my hands and can’t believe they’re 75 years old”, he said to me last year. I regularly got to tell him that I genuinely believed that he was the most imaginative photographers the UK had ever produced. There was also a gloriously subversive element to his photographs that honoured his origins, and the idea of work as physical labour. Expressed subtly within his practice, the working man and woman were often elevated and heroic.

Brian’s constant presence, ongoing commissions, initiating Kickstarters and public appearances, talking about his photography only the week before he passed, makes it harder to imagine his death and sudden absence. He left us on a high, busy and in demand.

There is so much more to say, we all have stories and warm memories of the man. RIP Brian, friend and innovator, we’re all going to miss you.

David Moore

–

We were shocked and saddened to learn of the sudden death of Brian Griffin. Just recently we were celebrating with him his latest project: he was in great form and gave a characteristically exuberant speech about his inspiration.

Brian was a brilliant image-maker with an incredible imagination. He was a creator of genuinely iconic images. Building from the surrealism of his 1970s work, including celebrated images for Management Today, in the 1980s he became the go-to person for record covers. This genius is celebrated in the book and exhibition Pop and the recent launch of Mode which presented his photographs for Depeche Mode. This may be Brian’s most celebrated work but wherever he turned his gaze he created something extraordinary. As recent commissions show, in his mid-seventies his brilliant imagination remained undimmed.

As well as his unforgettable images, I will remember Brian as a generous friend, a caring person, and someone with the gift of transforming kind words into practical deeds. When I mentioned the difficulties of fundraising for the Centre for British Photography, given the present economic and political climate, he really stepped up. The recently launched grants programme owes much to his help.

I will also remember Brian for his passion and enthusiasm and wit. He was always busy, always making plans for the future. He was delighted that in his mid-seventies he was still in such demand and he enjoyed his recent collaborations with a watch company and a wine maker which brought his creativity to new audiences. He was also looking forward to new collaborations that included an unexpected project that he’d recently received that involved him going on a cruise liner!

At our most recent meeting we discussed staging a solo show of his work. I am sad that we will no longer be able to work together on this exhibition but hope that it will still take place as a tribute to him.

I firmly believe that Brian is one of the greatest photographers this country has produced. He had a remarkable career filled with lasting images that span half a century but he still had so much to give. His death is a huge loss.

James Hyman

–

I first met Brian Griffin in 2012, not long after I had begun working as Curator at Derby QUAD. Preparations were underway for FORMAT 2013 and Brian’s passion, energy, humour and dedication to the FORMAT cause as our Patron was both thrilling to watch and displayed a deep and lasting commitment to the aims and ambitions of the festival. In essence I was in awe of him; this legendary figure had seemingly effortlessly created a body of work that will stand the test of time. I often asked him about the almost mystical way in which he created his images and film works. His was truly a ground-breaking practice, but also one that was built on the real and true foundations of photography.

I witnessed first-hand the way in which he constructed an image, or an outstanding set of images, on two occasions. The first was his project Tram Man, shot on location at Crich Tramway Museum in 2019. Working with his talented assistant Ravi Chandarana (and I think there is a long list of former assistants who learnt so much from Brian), I watched the ease in which Brian marshalled, directed and cajoled the models during the shoot. But I also saw the huge amount of work and patience it took to get just one magnificent image. The resulting set of images had an almost ‘old-school’ glamour to them, shot through with that unmistakable Brian Griffin style and substance; and ‘otherworldliness’. Another instance was when I had the opportunity to curate his exhibition, Black Country Dada 1969 – 1990 in QUAD Gallery in 2021. Handling each framed image was like handling a precious, iconic object. During the install Brian showed me his iPhone, where he had taken a photograph of one of QUAD’s technicians from the side, the bright red of a laser level outlining the contours of the tech’s face in profile. This astonishing image alone, opportunistic in a way, marked out decades of experience and knowledge of how to take a picture; but also spoke of a deep and enduring talent. He was one of a kind. I’ll miss our phone calls and laughter-filled chats face to face; and I’ll miss Brian’s signature goodbye: “love ya Pete!”. And we all at FORMAT and QUAD, myself very much included, loved him. Thank you Brian.

Peter Bonnell

–

Brian Griffin we’ll miss you dearly. Above all a friend, mentor and father figure over the last 8 years.

I was fortunate to be part of his surreal world lighting his sets and was able to dive into his weird and wonderful imagination. His mastery firstly was psychological: he played the perfect game to get exactly what he wanted out of a subject. Like a dance, intuitively I’d manoeuvre the light whilst he probed away with the subject, observing them in the upmost detail. I learnt the power of grids, channeling that light so precisely…often leaving the retoucher very little to do.

He could make a man working in an office dip his hands in Swarfega and a teacher wear a butcher’s glove. It was incredible to witness the use of props unfold into the portrait. The subject felt so intrigued, they always want to play ball to understand where he’d take the final result.

I’d describe Brian as neuroscientist; his precision had zero tolerance. I’m extremely lucky to be a close part of world in his later years. He was one of the great portrait photographers of our time.

Brian passed away very peacefully and has left a permanent imprint on my soul… he called everyone “young”… your legacy lives on and young Rav will do you proud. Big love and condolences to the family. RIP Mr Griffin.

Ravi Chandarana

–

I was very sad to hear that legendary British photographer Brian Griffin has passed away. As a working-class person who achieved fame and fortune in the 80’s with his effortlessly creative work, Brian was an obvious inspiration to myself and many others starting out at that time. He had developed a very distinctive visual signature, and his images were instantly recognisable; the Management Today pictures were deliciously bonkers.

I got to know Brian much later, mainly at festivals and fairs in Arles, Derby and Paris. They say “don’t meet your heroes”, but meeting Brian was one of life’s greatest pleasures. Warm, supportive and very, very funny, it’s hard to imagine being at those events without him there. There will forever be a seat in the corner bar in Place du Forum in Arles with Brian quaffing petit Leffe beers and greeting scores of friends old and new, talking about photography, having a gossip and sharing his latest plans for a new book or exhibition project. Rest in peace, Maestro Bri. ♦

Graeme Oxby

Brian Griffin (1948-2024)

Images:

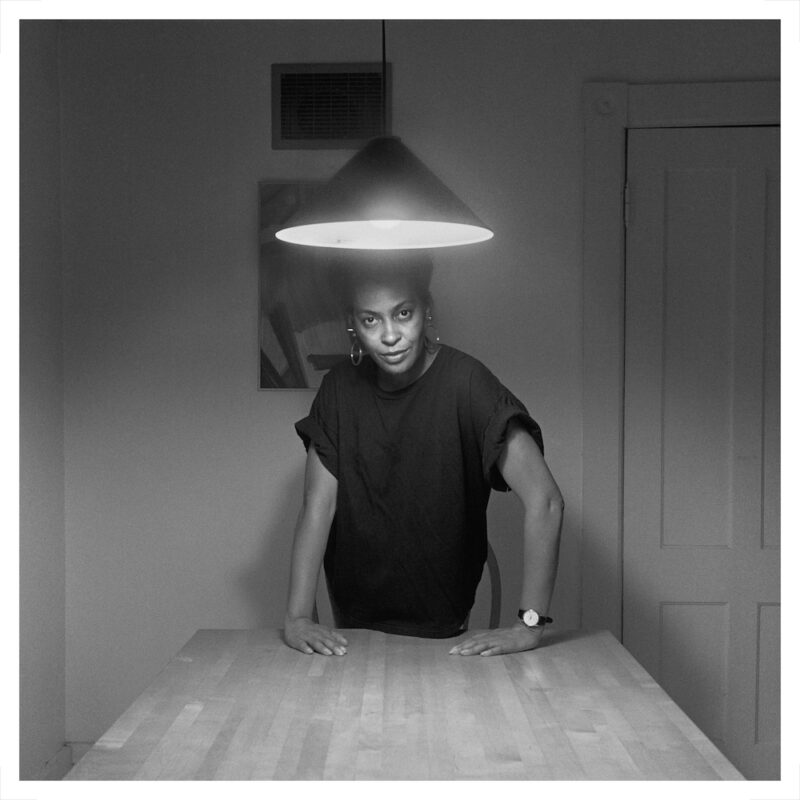

1-Brian Griffin, Carpenter, Broadgate, City of London, 1986. Courtesy MMX Gallery, London © Estate of Brian Griffin