Dafna Talmor

Constructed Landscapes

Essay by Duncan Wooldridge

Peter Geimer’s remarkable study of photography’s pre-history and its history of accidents, titled Inadvertent Images: A History of Photographic Apparitions, opens with an important photograph: André Kertész’s Broken Plate of 1929. Kertész’s image, Geimer reminds us, could have held a caption ‘Paris’ or ‘View of Paris’: it began its life as a depiction of a sharply descending Parisian street in the 18th arrondisement, with a view over to the spire of Notre-Dame de Clignancourt. Somewhere in advance of its printing, the glass plate was broken – a forceful but precise wound ruptures its surface on the left of the image, the whites of shattered glass spraying from a new dark centre. It is unclear whether this alteration was intended or entirely accidental – Kertész was a participating Surrealist, but also a working photographer – but after the event of its rupture, the image no longer exists solely as a view of the city: it draws attention to its materials and surfaces, equal to or greater than its subject. The illusion of photography is shattered.

Geimer purposefully weaves a ‘pre-history’ of photography with accidents and abstractions, showing them to be core to how photography functions: these had been written out of the familiar history of the medium in favour of a narrative that claims to come into being not by the gradual development of ideas, trial and error, and unintended consequences but in the instantaneity of authored invention. Such a narrative is convenient, Geimer reveals, because it plays to the reinforcement of multiple orthodoxies, including a clean and uncluttered history of photography itself. His purpose here is not just the demystification of invention as a moment of spontaneous genius, however, but to make a well-made but controversial argument as far as photography’s essential properties are concerned: that depiction did not come to photography before abstraction. Geimer shows that visibility and representation emerged from within the haze of photography’s abstract traces. Abstraction and fragmentation were always part of the image, and not the late inventions of art: in fact, any conception of photographic truth needs reconfiguring to include the role played by the camera operator.

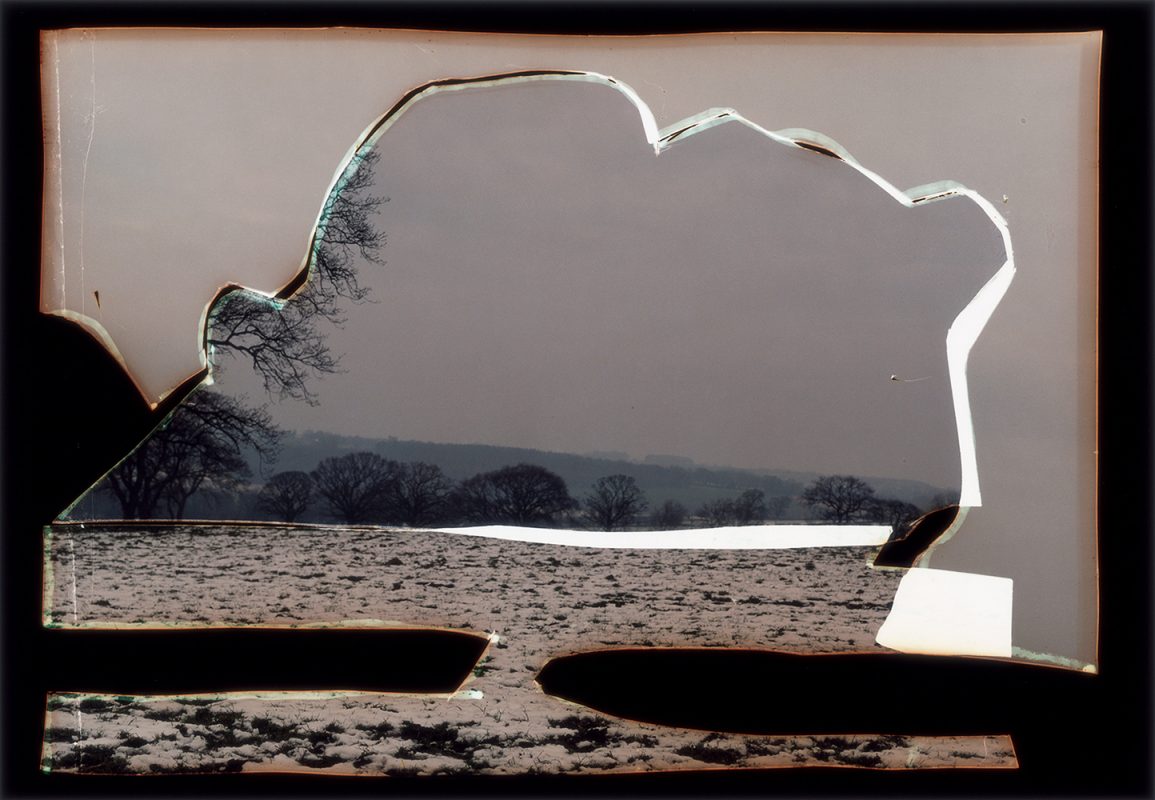

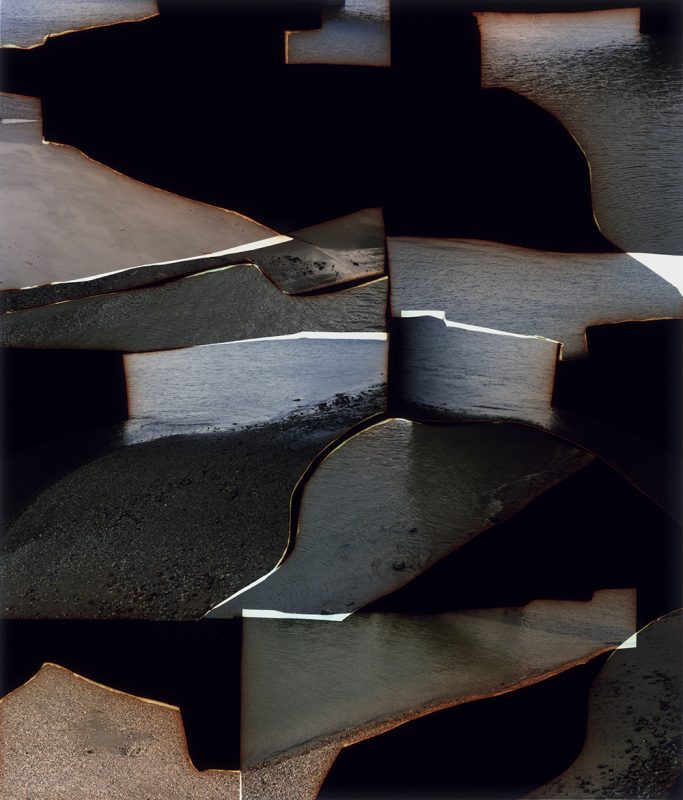

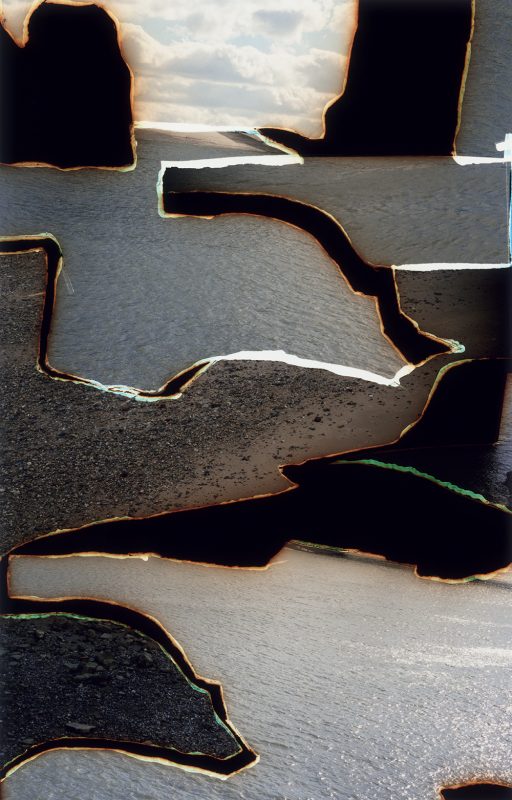

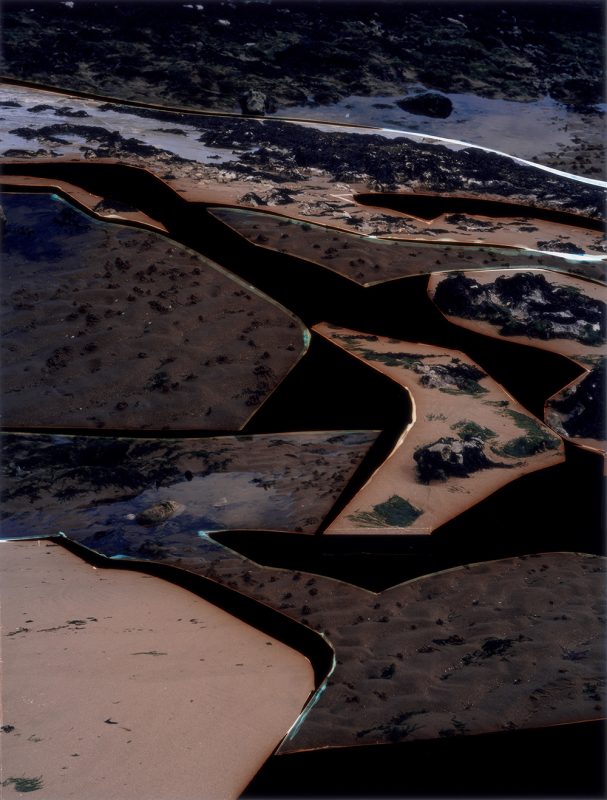

Against this background, the photographic landscape or ‘view’ is revealed to be a complex ensemble, made of studies, tests and alterations, and not as an object of contained romantic sublimity. In her ongoing series Constructed Landscapes, Dafna Talmor tackles the difficult task of depicting a view in both direct and complex layers. Her images are at first overt as disassembled exposures, but they resist completion in their reconstruction, opening out to larger questions about the landscape image, its history, and its place in our conceptions of nature. From its initial formal fragmentation, Untitled (LO-TH-181818181818-1) slowly reveals a variety of surfaces that blend and diverge from one another. Patches of rippling water echo with the dappled surfaces of the ground. We have nothing to assure us that this isn’t one location, and so we attempt to recompose it, to understand its multiple positions. We quickly give room, albeit unconsciously, to a multiplicity of parts from which the landscape springs.

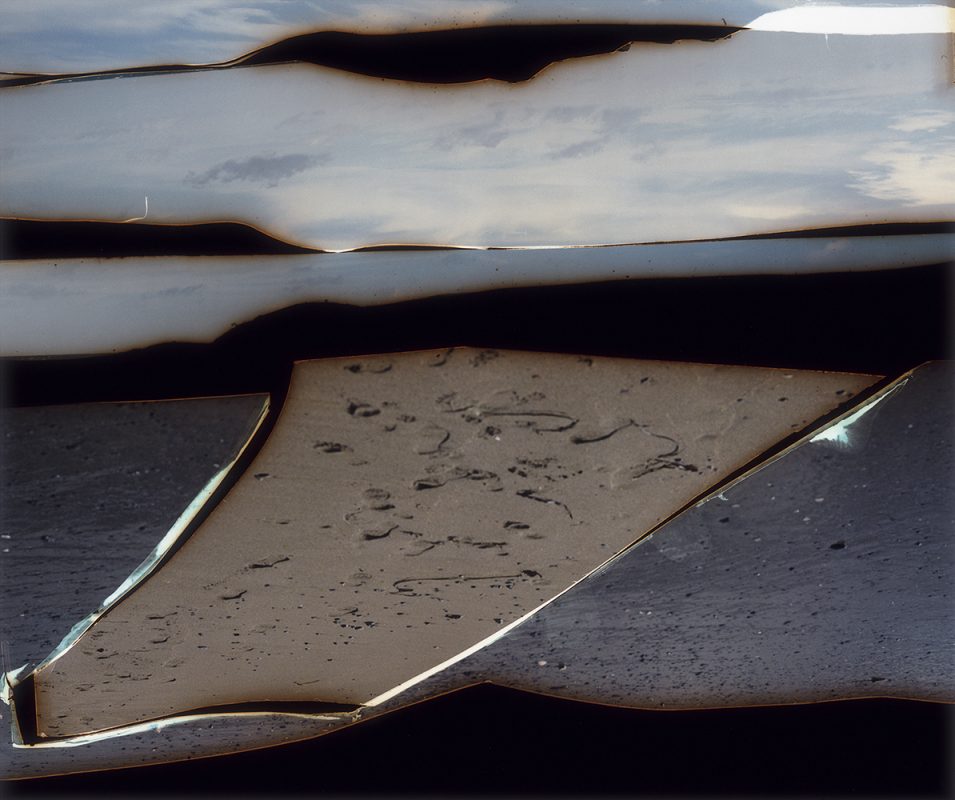

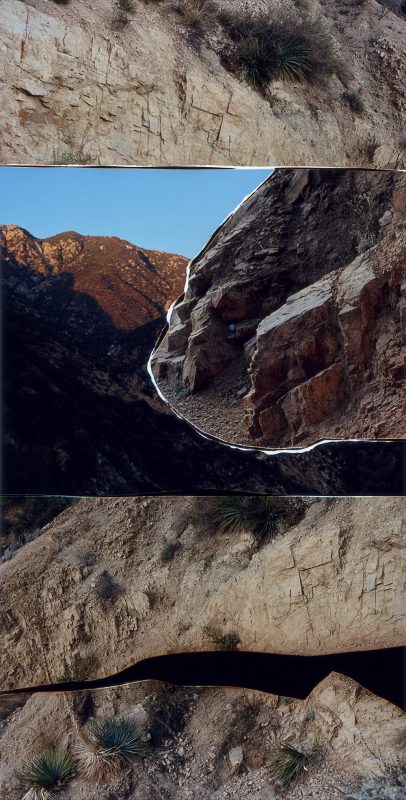

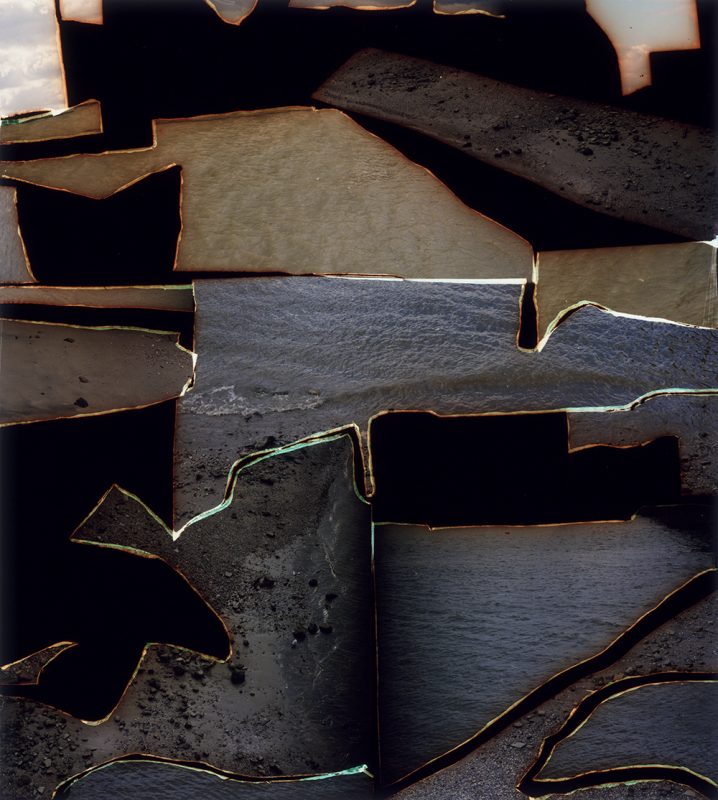

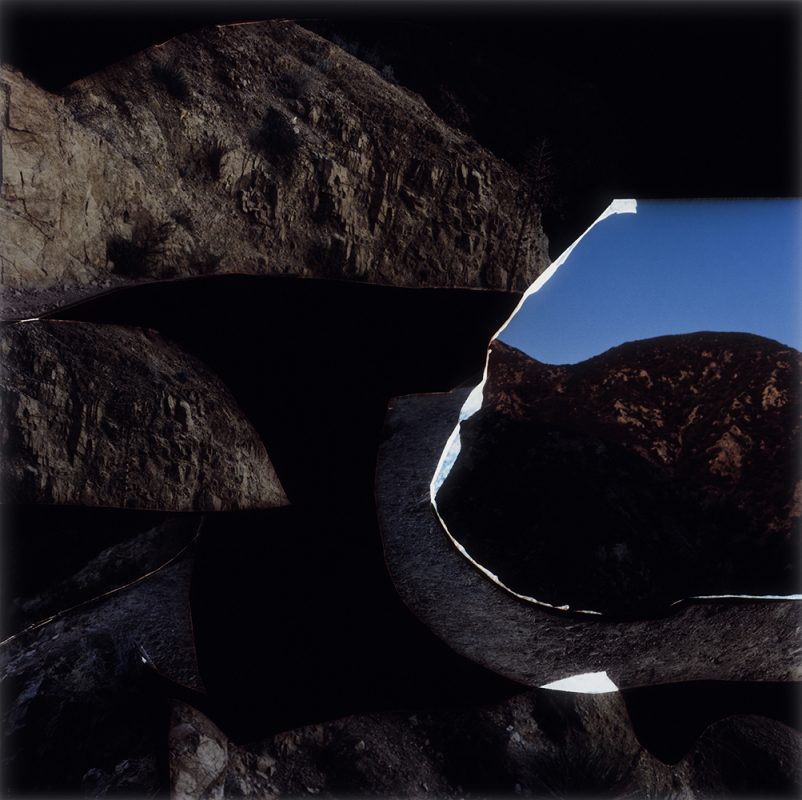

Composed from multiple negatives – so that images, views, and perhaps even places are intermingled – her images balance between a pictorial space constructed by fragments and the logics of a disciplinary photographic frame that seeks a completed image. Untitled (BR-1414-1) hovers between one and what seems to be two images, comprised as it is of oscillating tonalities that may or may not merge together. Each contains rupturing black and white flashes which reveal the construction of the negative as a cut, splintered, taped and crafted object. White flashes arise from overlapping parts of the negative, whilst black spaces – which sometimes appear to be both deep and impenetrable, but also sit at the surface as a flattened foreground, like Kertész’s shattered plate – are produced from empty spaces between pieces of film. Untitled (EA-131313-4) is both broken and joined by black lacerations. Its cliff surfaces stacked at destabilising angles, which reveal their assembly whilst building a perspective which threatens perceptually to collapse upon itself. The negative is an object from the beginning of Talmor’s project: this does not collapse the notion of her photographs as landscape images in a tangible, legible sense. Nevertheless, it forces us to call into question quite what we understand by landscape as a descriptor.

An aspect of this disassembly of landscape comes from Talmor’s reading of the history of the genre, and its involvement, as Geimer also shows us, with technological limit and the gradual problem solving that leads towards representation as we know it. The challenges of depicting the landscape were revealed in the early histories of photography, as wide angles and variation in light necessitated the invention of multiple exposures and combination printing. Blown out skies and darkened landscapes blighted the painterly aspirations of early practitioners, and Talmor is quick to identify the combination print as a rarely considered object and construct in the overcoming of photography’s raw qualities. Her earliest Constructed Landscapes use the quasi-empty space of the landscape as a site for overprinting, with ghostly impressions emerging in the skies of many of her photographs. Such is the significance of this capacity – to print and adjust the sky alongside the content of the land – that we are forced to reconsider what it brings into being. Can we imagine for a moment what the history of photography would look like without dodging and burning, multiple negatives and the craft of the darkroom? Such a history would surely give rise to a thousand, a million abstract photographs. Certainly, at the very least, such conditions abolish romantic conceptions of immediacy. Talmor places the making of the image in the darkroom as a central gesture where it is often downplayed. In place of the singular image – the persisting myth of the event as captured solely within the compression of the shutter – the picture’s multiplicity comes forth. And Talmor reminds us also that multiplicity is more than just the reproducibility of a print: it is embedded in the stitched, collaged and montaged techniques that span Pictorialist abstractions right through to the labour of Rejlander’s Victorian tableaux.

Whilst Talmor produces assemblages peppered with marks, punctuations and clues to the images’ making, her initial photographs of subtly significant and undulating spaces are not quickly graspable, and are not spaces of rapid digestion. They are images that Talmor herself claims cause a certain doubt upon initial inspection: are they interesting or revealing enough within the contexts of our current image world? Do they contain sufficient traces or semblances of event or narrative? That is to say, they are sites which do not give up their sense of specific place quickly, being neither romantically overblown nor documentarily dramatic – which is also to say, they are like most spaces, the many rather than the very few. Instead, they require time and an uncovering of the layers that reveal the histories of place. Talmor’s assemblage of images constructs a more complex condition of presence, and a viewership that is necessarily, as a response to the sealed presentation of most landscapes, deconstructive or archaeological.

Much could be made of the specifics of place and the locations in which Talmor photographs, though this seems like a red herring liable to being over-interpreted in a search for hasty completion. In fact, Talmor makes no clear reference to their location, titling her works with the encoded system of negative parts which comprise the images, and consciously omitting by cropping or cutting, manmade objects that might enable recognition. It seems fruitful to hold our desire for certainty within the image at bay for at least a moment. We are liable to place the landscape at a remove, to see it as natural – beyond us, or affected by mankind – i.e someone else, both of which concoct a distance that permits our indifference. Images of specific, far away landscapes and events place us at just such a remove, as many critiques of documentary have evidenced. Talmor instead positions the viewer as a constructor of the landscape, a contributor to space: the photograph may appear flat, but the image becomes tangible and animate in Talmor’s actions and the constructive gaze it calls upon. The landscape is non-descript, but it is formed and conditioned by human actors. The spaces of Talmor’s photographs do not need to be identified, precisely because they take as their subject not a place that we can distance ourselves from, but somewhere larger, beyond place: a landscape always already constructed and contested, that we are part of, whatever our connection to it. We must piece the landscape together in order to understand it. We’ve made it that way, after all. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Dafna Talmor

—

Duncan Wooldridge is an artist, writer and Course Director of Photography at Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London. He writes regularly for Artforum, Art Monthly and Elephant. In 2011 he curated the exhibition Anti-Photography at Focal Point Gallery, and in 2014 John Hilliard: Not Black and White, at Richard Saltoun, London.