Writer Conversations #2

David Levi Strauss

David Levi Strauss is the author of Co-illusion: Dispatches from the End of Communication (MIT Press, 2020); Photography and Belief (David Zwirner Books, 2020, and in an Italian edition by Johan & Levi, 2021); Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow (Aperture, 2014); In Case Something Different Happens in the Future: Joseph Beuys and 9/11 (Documenta 13, 2012); From Head to Hand: Art and the Manual (Oxford University Press, 2010), Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics, with an introduction by John Berger (Aperture, 2003, 2012 and in an Italian edition by Postmedia Books, 2007) and Between Dog & Wolf: Essays on Art and Politics (Autonomedia, 1999 and 2010).

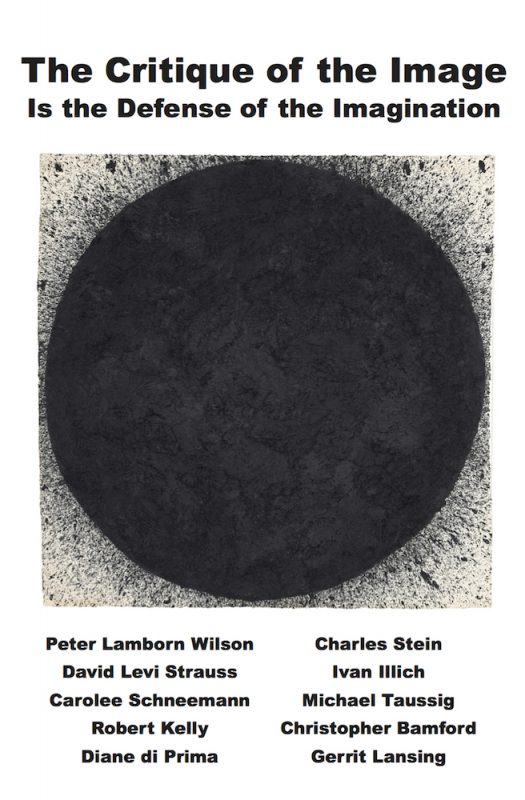

He has also co-edited To Dare Imagining: Rojava Revolution, with Michael Taussig, Peter Lamborn Wilson and Dilar Dirik (Autonomedia, 2016, and in an Italian edition by Elèuthera, 2017) and The Critique of the Image Is the Defense of the Imagination, with Strauss, Taussig and Wilson (Autonomedia, 2020). From 2007–21, Strauss directed the graduate programme in Art Writing at the School of Visual Arts, New York, US.

At what point did you start to write about photographs?

In 1975, when I was a 22-year-old poet, I went to study photography with Nathan Lyons at Visual Studies Workshop, which, at that time, was the best photography school in the US. MIT Press had just published Nathan’s landmark book of photographs, Notations in Passing (1971). When I first attended Nathan’s seminar, I handed him a handwritten copy of an essay I’d written in response to Notations in Passing, titled “The Ontology of the Eye, or A Stall of Cows, A Stall of Images”. It began this way: ‘The eye cannot be separated from the brain or memory. Visual data, like all sensory data, are immediately plugged into the complex mega-memory of the brain/soul.’ The other students in the seminar thought this was the most impertinent act they’d ever witnessed, but Nathan liked the piece. That was the beginning.

What is your writing process?

My process is ridiculously labour intensive and inefficient. I write 50 pages to get a page. I first produce an unwieldly mass of language, and then carve it down. It takes an incredibly long time. It’s a sculptural process, from the inside-out. I use montage and magic. The first sentence usually comes last.

It feels like there is something very photographic about this, the quantity of writing and the carefully selected final outcome, its compulsive recording and intensive editing. In the same way that a photographer develops a series of strategies, shortcuts and go-tos, are there tools or strategies that facilitate your final montage? How do you know that writing reaches the stage where you can write that first sentence?

I’ve never thought about my writing process having a correlative in photography, but I think you’re right. It is a process of selection. Each word is chosen from a very large number of possibilities, and, when each word is chosen, it affects every other word around it. The larger currents that determine form are rhythm and rhyme, at the level of phrase, clause, sentence and paragraph. If you get too attached to the individual words, you lose the music, and, if you lose the music, you lose the reader.

In the end, you’ve got to be able to separate yourself from the writing, and look at it as if someone else wrote it. Only then can you get to that level of absolute ruthlessness that is necessary in rewriting.

For me, the process is endless. At a certain point, someone takes it away from me and then it’s done. Like Duke Ellington said: “I don’t need time. What I need is a deadline.”

What are the questions or problems that motivate your writing?

I write to find out what I think about things. I try to focus on the persistent questions: Why are we here? What does it mean? How and why do we believe technical images the way we do? How do these images actually work? Who benefits from this?

Right now, I’m trying to write about the End of the World, and the first question is: What is the world? This puts me immediately back at the image of the world. Most of the questions I deal with send me back to the image.

Something really distinctive in your recent writing is the way that images not only record the world but are informing it, producing it even. And your writing, dialogically, seems to want to change the image in turn. Do you write in order to challenge, and even change what the image might be?

Yes, absolutely. I want to change the image of the world, in however limited a way I can, through enactment and persuasion. One of the biggest problems in our time is that we no longer have a viable social image of the world.

What kind of reader are you?

I’ve been a driven, voracious reader since I first learned to read, before starting grade school, and that has never changed. I read to live. When I was a child, my father discouraged me from reading, and sometimes punished me for it, thinking that it was an excuse not to work. So, I read in secret, sometimes literally in the closet and under the sheets. The act of reading always felt illicit to me, and this feeling never really went away. When I began to be encouraged to read in school, I always thought someone, surely, would realise that what I was doing was wrong, that I could go anywhere and be anyone when I read, and those in charge would realise how dangerous this was and stop me, but no one ever did.

How significant are theories and histories of photography now that curation is so prominent?

More significant than ever, I think. Photographic images are a significant part of the mechanism of social control in the world today, and we need to understand how they work and where they came from in order to resist this control.

I taught from 2001–05 at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, New York, and I became dismayed by the prevalence of what I came to call “curatorial rhetoric”; writing that borrowed terms and concepts from various specialised languages and used this jargon to protect the writer, and the reader, from experiencing the art in question. When I despaired of getting curators to abandon this kind of prophylactic rhetoric, I began to encourage them to hire outside writers, instead, to write catalogue essays.

You were Chair of the School of Visual Arts in New York’s celebrated Art Writing programme until very recently, overlapping with your time at Bard. In what ways did teaching writing inform your own practice?

By the time I became Chair of the Art Writing programme, I had been writing seriously for over 30 years, and had already gone through many transformations. But teaching certainly made me more aware of the difficulties and the dilemmas of writing in the present, as experienced by my younger students.

Teaching is a fundamentally optimistic act, like writing. In both, you’re imagining your reader/student into existence – imagining the very best of them. And I’ve been extremely lucky to have so many of my students join in this mutually transformative act.

What qualities do you admire in other writers?

Courage, honesty, generosity, risk and kindness.

What texts have influenced you the most?

The writings of John Berger, Walter Benjamin, Susan Sontag, Paul Virilio, Vilém Flusser, Jacques Ellul, Edward Said, Aimé Césaire, Albert Camus, Paul Valéry, Hannah Arendt, Simone Weil, Marsilio Ficino, Leo Steinberg, Leon Golub, Jimmie Durham, Amiri Baraka, Linda Nochlin, Lucy Lippard, Elena Poniatowska, Guy Davenport, James Baldwin, Flann O’Brien, Samuel Beckett, Peter Lamborn Wilson, Michael Taussig, William Burroughs, Paul Bowles, Jean Genet and Pier Paolo Pasolini.

And the poetry and prose of Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, John Keats, William Blake, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, H.D., Charles Olson, Robert Duncan, Robin Blaser, Diane di Prima and many others in this lineage.

What is the place of criticality in photography writing now?

The more pressing question is: What is the place of criticality, or critical thinking, in the social realm today? Our current communications environment has reduced critical thinking to personal preferences and opinions, and amplified anger and fear, and that has made it difficult to engage difficult questions in the larger social frame with criticality. We need to find new ways to talk about important things.♦

Further interviews in the Writer Conversations series can be read here.

Click here to order your copy of the book

—

Writer Conversations is edited by Lucy Soutter (University of Westminster) and Duncan Wooldridge (Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London), upon the invitation of Tim Clark (1000 Words and The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University).

Images:

1-David Levi Strauss © Sterrett Smith

2-Book cover of David Levi Strauss, Co-illusion: Dispatches from the End of Communication (MIT Press, 2020)

3-Book cover of David Levi Strauss, Photography and Belief (David Zwirner Books, 2020)

4-Book cover of The Critique of the Image Is the Defense of the Imagination, eds. David Levi Strauss, Michael Taussig and Peter Lamborn Wilson (Autonomedia, 2020)