Liz Orton

Every Body Is An Archive

Book review by Diane Smyth

When Liz Orton’s daughter was 13 months old, she had to have a nuclear imaging scan at London’s Great Ormond Street Hospital. Though it’s a hospital famous for its work with children, and though Orton was assured that the scan would be non-invasive, the procedure turned out to be traumatic. Injected with a dye, her daughter had to be kept motionless for about 20 minutes, something very difficult for most wriggly toddlers to achieve. So she was strapped to the bed with Velcro restraints and immobilised with sandbags, which felt, says Orton, anything but non-invasive.

The experience got her thinking about medical imaging and the ‘medical gaze’, setting her off on a very long path which has now culminated in a book, Every Body Is An Archive, designed by Valentina Abenavoli of AKINA. Funded by the Wellcome Trust, Orton realised the project from 2014-19, working with the medical imaging team at University College London Hospital, sitting in as scans were taken of patients, teaching herself to use medical imaging software, doing collaborative re-enactments with individuals who’d had scans, and plundering the photographs in the Clark’s Positioning in Radiography manual (1939). Every Body Is An Archive includes essays by John Hipwell, computational medical imaging scientist; Professor Steve Halligan, radiologist at UCL Hospital and Head of the Centre for Medical Imaging at UCL; plus Dr Henrietta Simson, artist and fine art lecturer, and throughout, Orton aims to do something deceptively simple – to unpick the medical gaze.

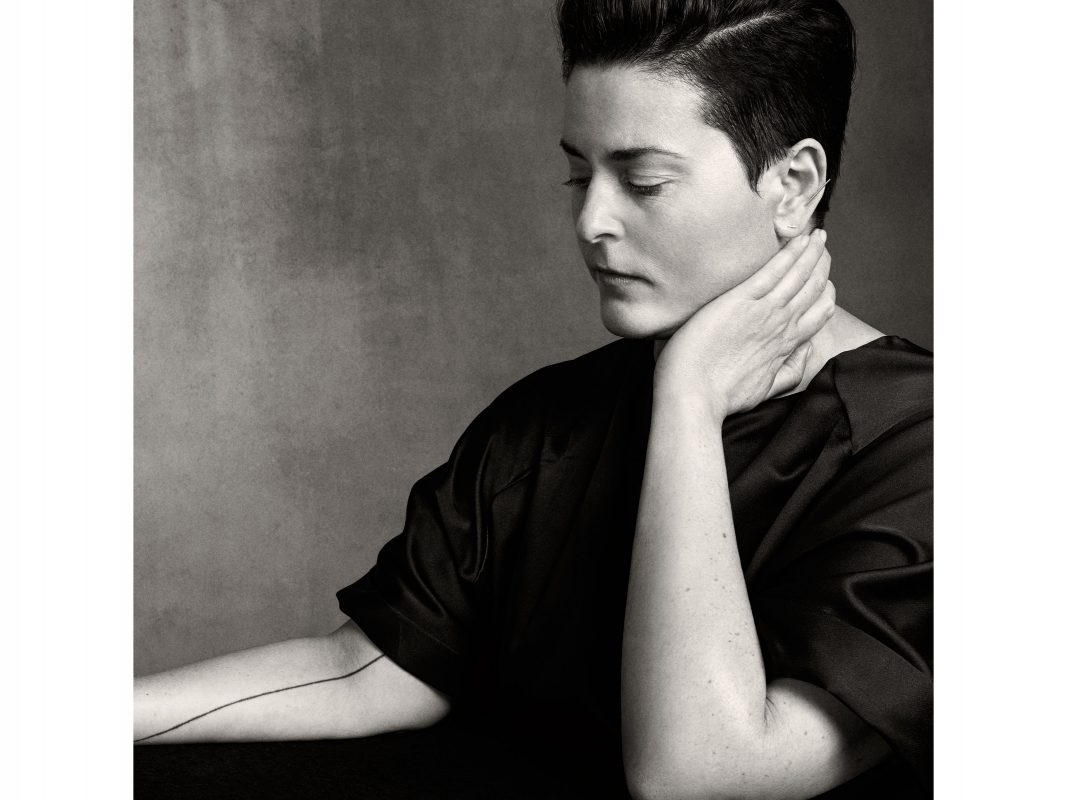

As a term first proposed by Michel Foucault in his 1963 book The Birth of the Clinic, it refers to the dehumanising medical separation of the patient’s body from his or her person or identity. At the hands of the medical profession, so the argument goes, we’re supposed to abandon our cultural, sexual, or personal understanding of our bodies and think of them as medical objects; if we’re the only naked ones in the room, this isn’t supposed to feel strange, and if we’re touched in intimate places, we’re supposed to take it on the chin. “Paradoxically, in relation to that which he is suffering from, the patient is only an external fact; the medical reading must take him into account only to place him in parentheses. Of course, the doctor must know ‘the internal structure of our bodies’; but only in order to subtract it, and to free to the doctor’s gaze ‘the nature and combination of symptoms, crises, and other circumstances that accompany diseases’,” writes Foucault. Later he adds: “If one wishes to know the illness from which he is suffering, one must subtract the individual, with his particular qualities”. But as Orton points out, we don’t have different cultural, personal or medical bodies, we have just one, so in real life, this separation isn’t easy to achieve. Orton’s book is a deliberate refusal to try.

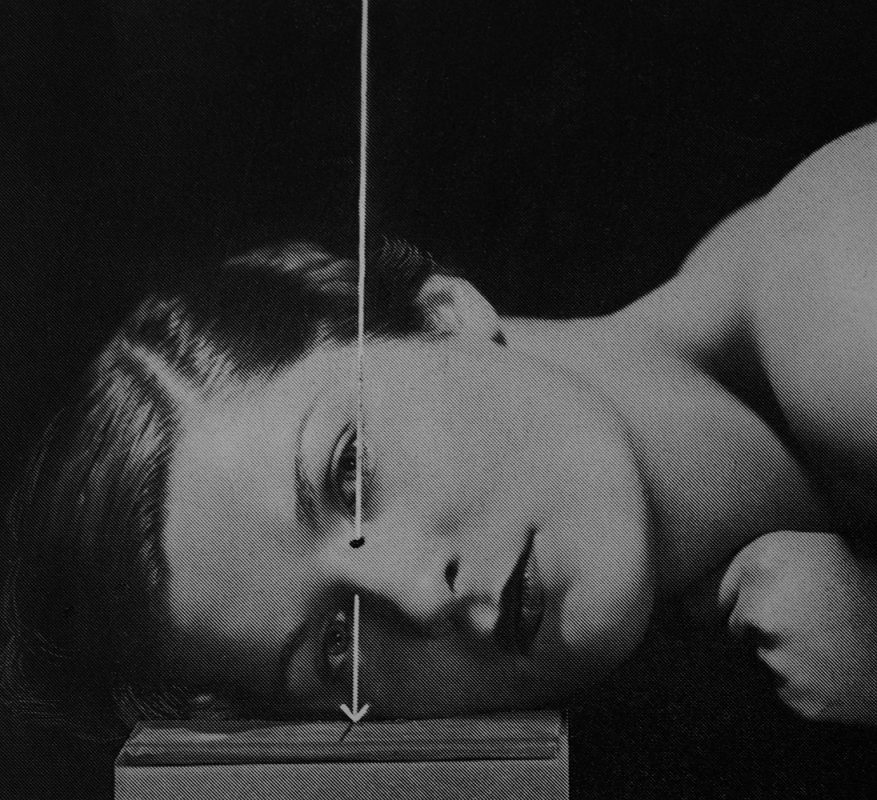

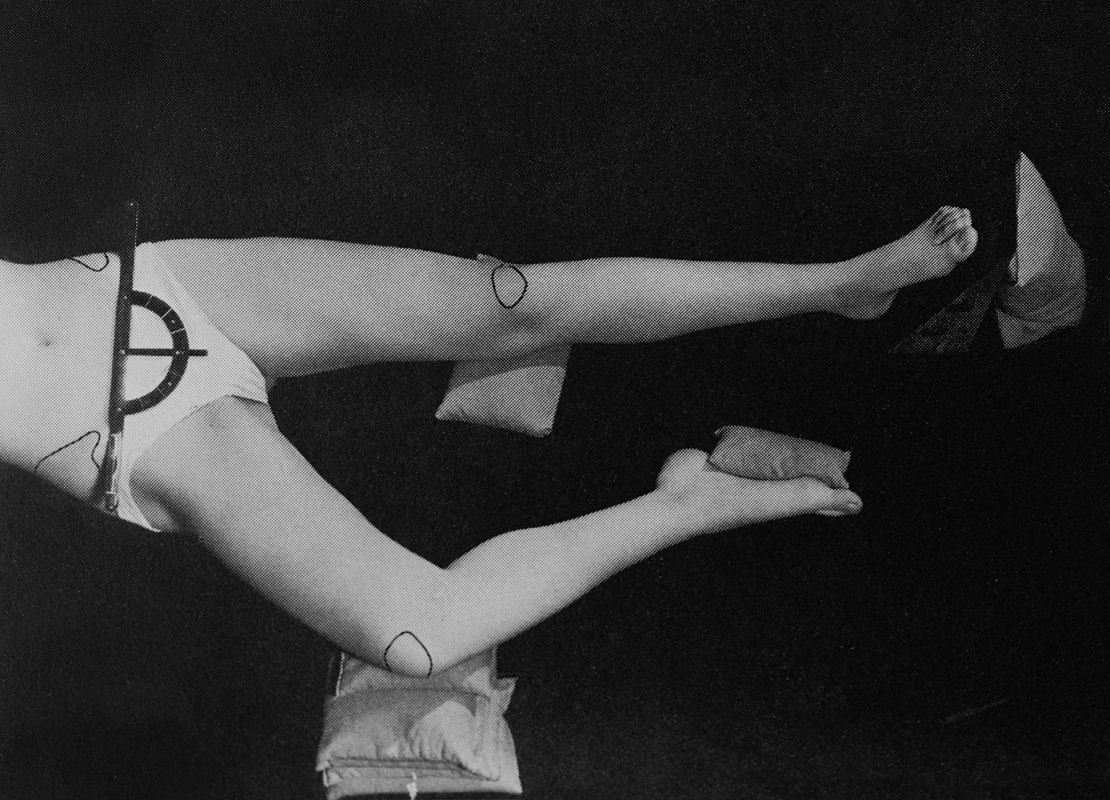

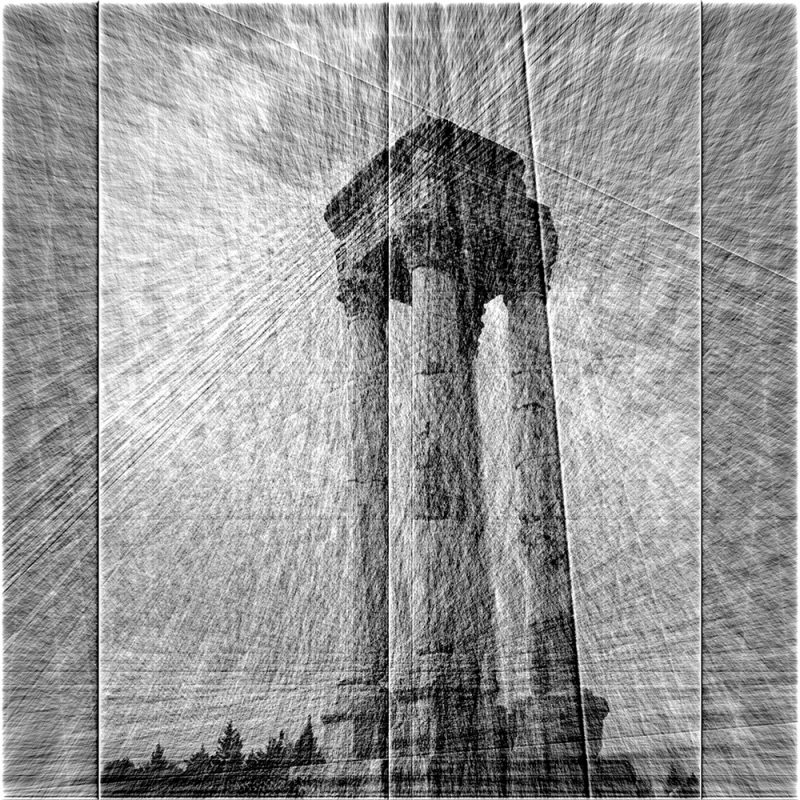

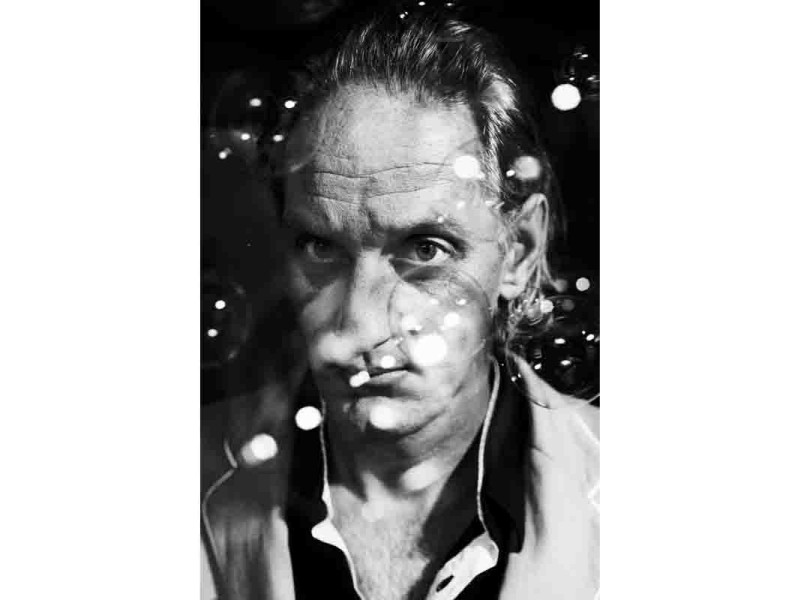

The images she uses from Clark’s Positioning in Radiography are meant to be diagrams, for example, helping professionals achieve the best results in their X-rays; Orton strips them of their context to show how surreal, kinky, and even fashionable they also are. Legs are placed akimbo, faces crudely bisected by lines in ways that cut across social norms for (female) bodies and the ways they’re represented; elsewhere computer-generated images create weirdly inhuman depictions of the human body. The re-enactments she staged, meanwhile, reinterpret the sometimes disempowering experience of being scanned to give back a sense of autonomy and control, to show scenes that look loving, threatening and even funny.

Orton’s book is also peppered with short phrases from those who have undergone scans, as they try to describe the images that have been taken of their insides. Patients often don’t get to see these images, Orton points out, and if they do, they usually lack the skills or the vocabulary to interpret them in conventional, medical terms. She lets them give it a go, and their homespun attempts are also surreal and witty, and heavily reliant on metaphor. “when you are poaching an egg, and the egg is a bit old, and all the white goes into the water”, reads one; “a ghost waiting for an embrace”, reads another.

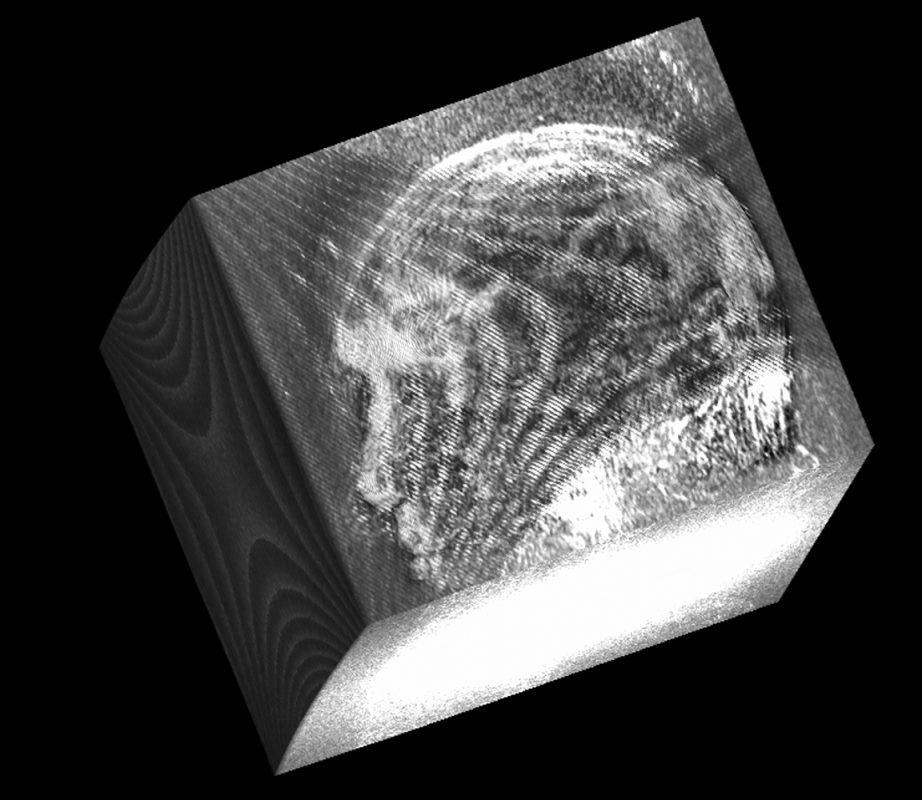

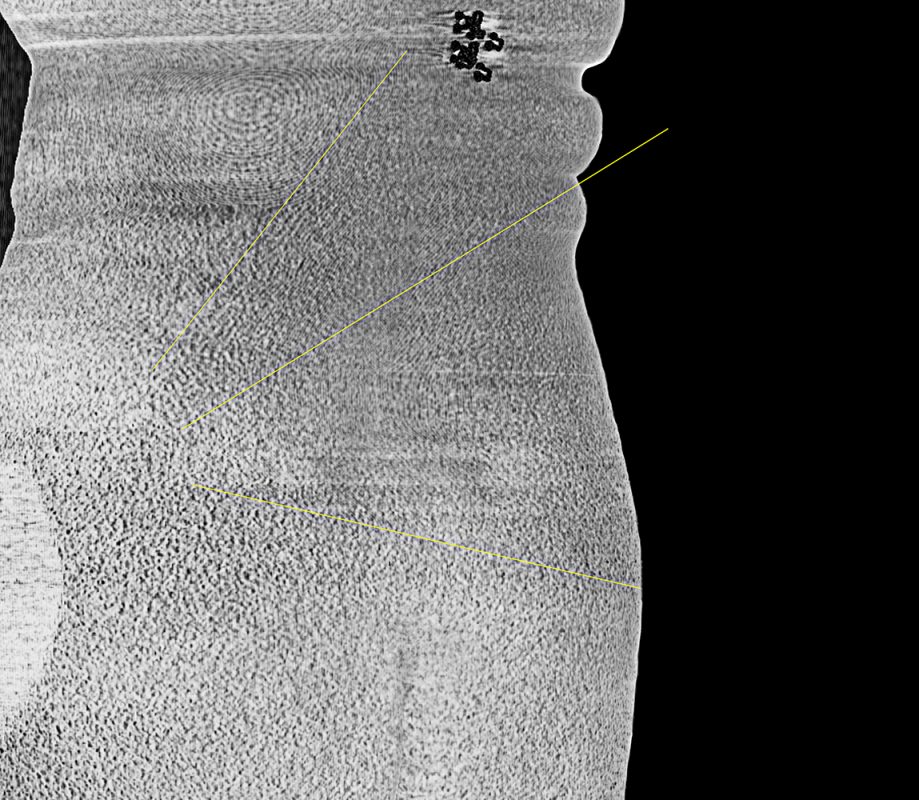

For Orton, it’s the fact that these interior shots are just that, interior, that’s so compelling – taken without physically puncturing the body but invading it all the same. It’s an approach that she deliberately eschewed, teaching herself to use radiological software but using it to build pictures of the outsides of bodies rather than breaching their boundaries. As such many of the resulting images are clustered together onto black pages in the book, where they’re printed with silver ink like X-rays. They look descriptive but also eerily strange, artefacts and interferences giving a distinctly digital effect.

And that’s of interest too since, as Orton points out, the medical body is now on the threshold of change, as computer sciences become more integral to healthcare. Medical images, for some time captured by computers, are increasingly interpreted by computers too – and unlike older forms of diagnosis, in which a doctor might talk with a patient about their symptoms and also their life, the patient need not even be present. Furthermore the image data sets are valuable too, both helping to train up the interpretative software but also as a resource in their own right, one that is governed by strict rules around privacy and ethics but, even so, one prominent radiologist has spoken in terms of a ‘gold rush’. In the era of Big Data, it’s worth considering what that data might reveal in conjunction with other information sets, and also about who owns them – medical imaging is a force for good, but considered as a means of surveillance, it’s at least got the potential for something less benign.

“Computer software and hardware systems operating across different sectors, through common platforms and constantly expanding networks, allow for an unprecedented integration of interests and systems in medicine,” Orton has written on her Digital Insides website. “The body is becoming part of this new informational economy, facilitated through new forms of biomedical management. It is being propelled into the fields of medical image computing, post-image processing, computer aided diagnosis, automated analysis, image-guided surgery/treatment, machine and deep learning, and image mining. The image is potential: in a computerised system, it is becoming generative in new ways, both as product and process.”

Or, as Professor Steve Halligan puts it in his accompanying essay to the book: “Ultimately, [the] work shows us what we have often forgotten due to pressure of work and what is obscured: that there is first and foremost a human being behind the image, and secondly that the experience of imaging often makes patients feel highly vulnerable.” ♦

All images courtesy the artist. © Liz Orton

—

Diane Smyth is a freelance journalist who works with publications such as The Guardian, The Observer, The FT Weekend Magazine, Creative Review, The Calvert Journal, the British Journal of Photography, Foam, and others. Prior to going freelance she wrote and edited for the British Journal of Photography for more than 15 years, and she has also curated exhibitions for The Photographers’ Gallery, Lianzhou Foto Festival and the Flash Forward Festival.