Duane Michals

Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals

Essay by Aaron Schuman

The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, United States

01.11.14 – 2.03.15

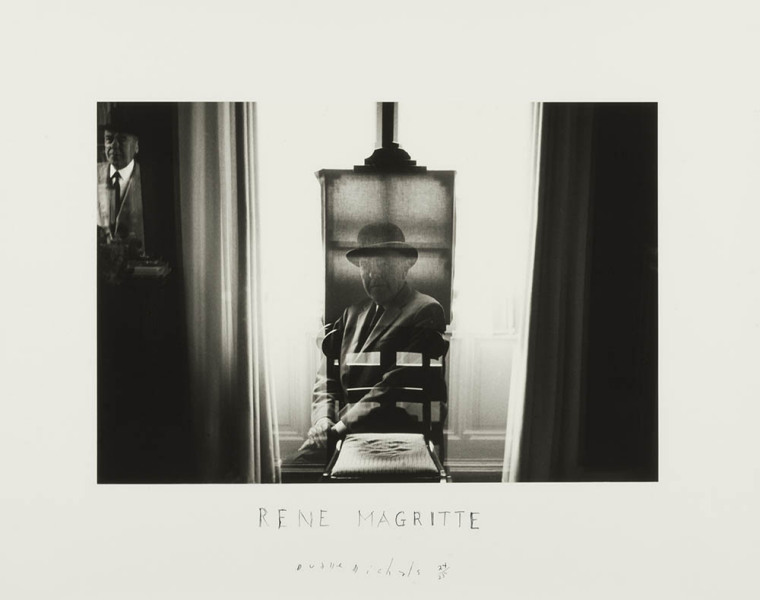

In the summer of 2013, I visited the National Art Library – housed in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum – specifically to delve into all of the Duane Michals-related material in their possession. Part of my assignment was to explore Michals’ influence on contemporary artistic and photographic practice over the course of his long career, and although the library was a treasure trove of monographs, histories, archival exhibition catalogues, leaflets, and so on, for some reason I was still coming up short in this regard. Frustrated, and needing a break, I abandoned the stack of books teetering over my assigned seat and wandered down to the museum’s photography galleries, situated directly underneath the library itself.

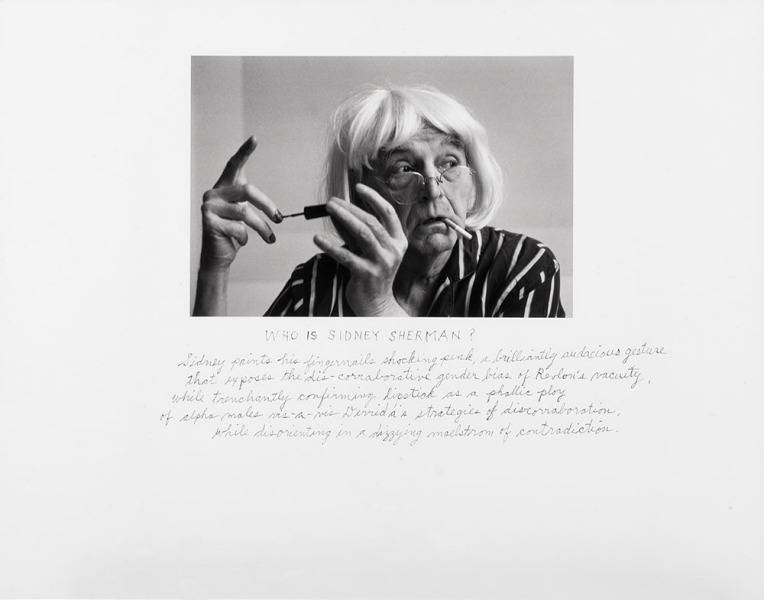

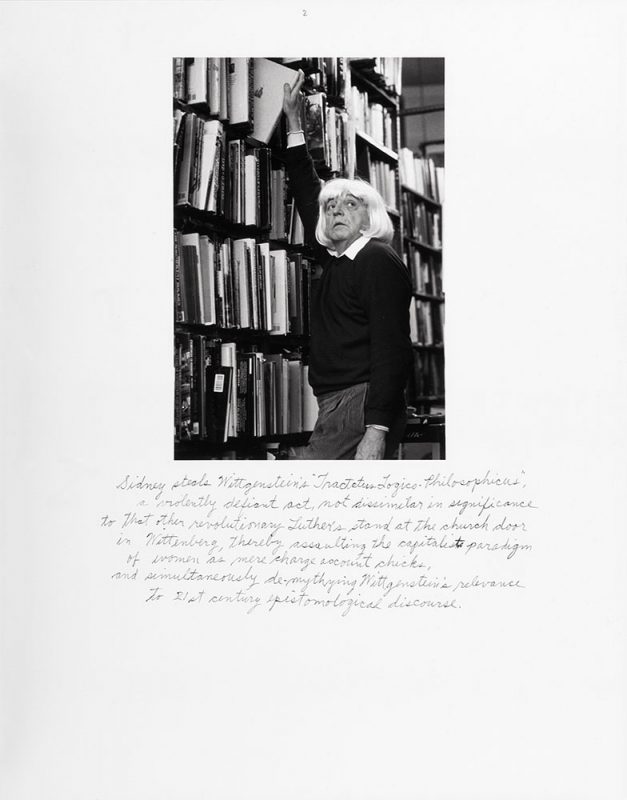

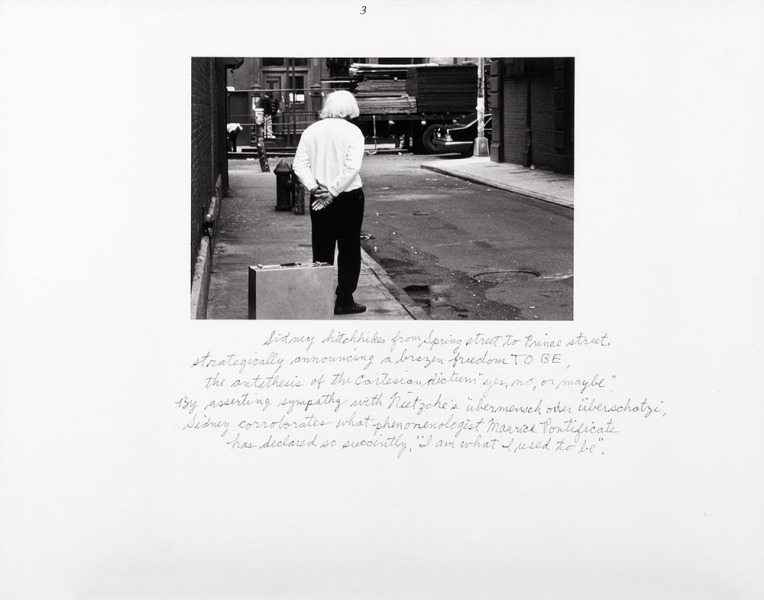

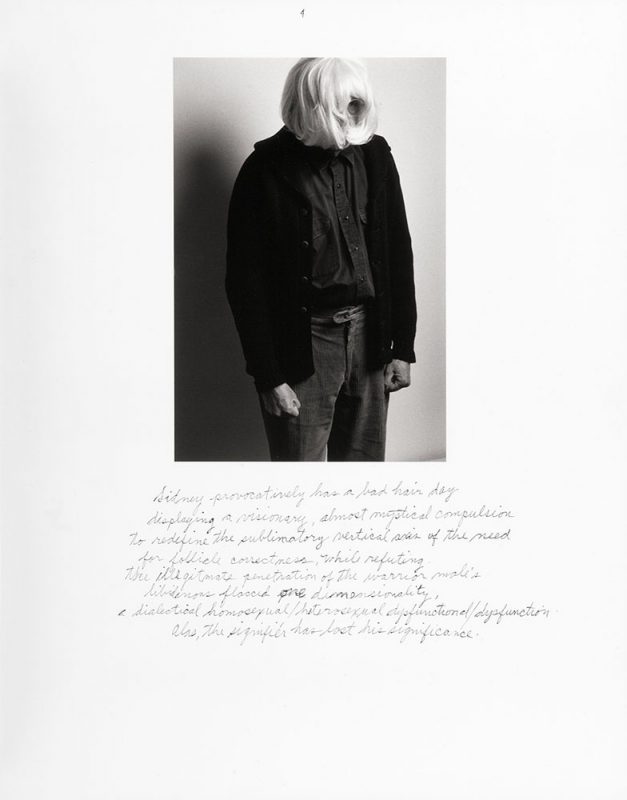

There I was surprised to discover a small exhibition entitled Making It Up: Photographic Fictions, which proposed to show works “by some of the earliest and the most recent photographers to use the camera to tell a story.” As the introductory wall text went on to explain; “For its earliest proponents, the staged photograph promoted the artistic value of the new medium.… For more recent practitioners, staging a photograph can refer to the artifice of contemporary culture.” With Michals’ series Who Is Sidney Sherman? (2000) fresh in my mind, I was both amused and chagrined that the show opened rather predictably with Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #74 (1980) – an image of Sherman standing before a screen projection of a New York City street, wearing an ill-fitting wig, a bright yellow coat, blood-red lipstick, and displaying a familiarly nervous look as she catches sight of something in the middle distance, just outside the right side of the frame. The caption beside it stated that Sherman’s work “critiques the stereotypical imagery and deconstructs feminine roles.” Despite the fact that the display had not explicitly invoked Derrida or the “phallic ploy of alpha males,” I couldn’t help cringing a little bit, feeling the sting of Michals’ sharp-witted art-world satire once again.

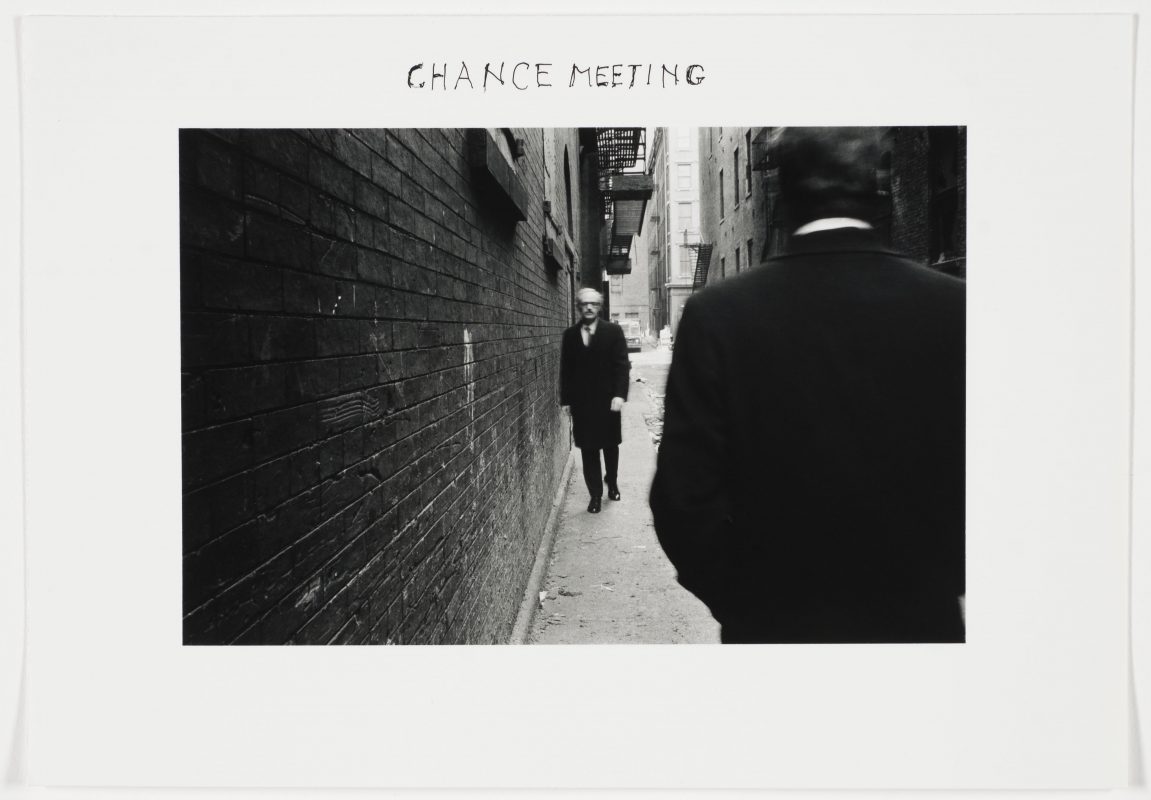

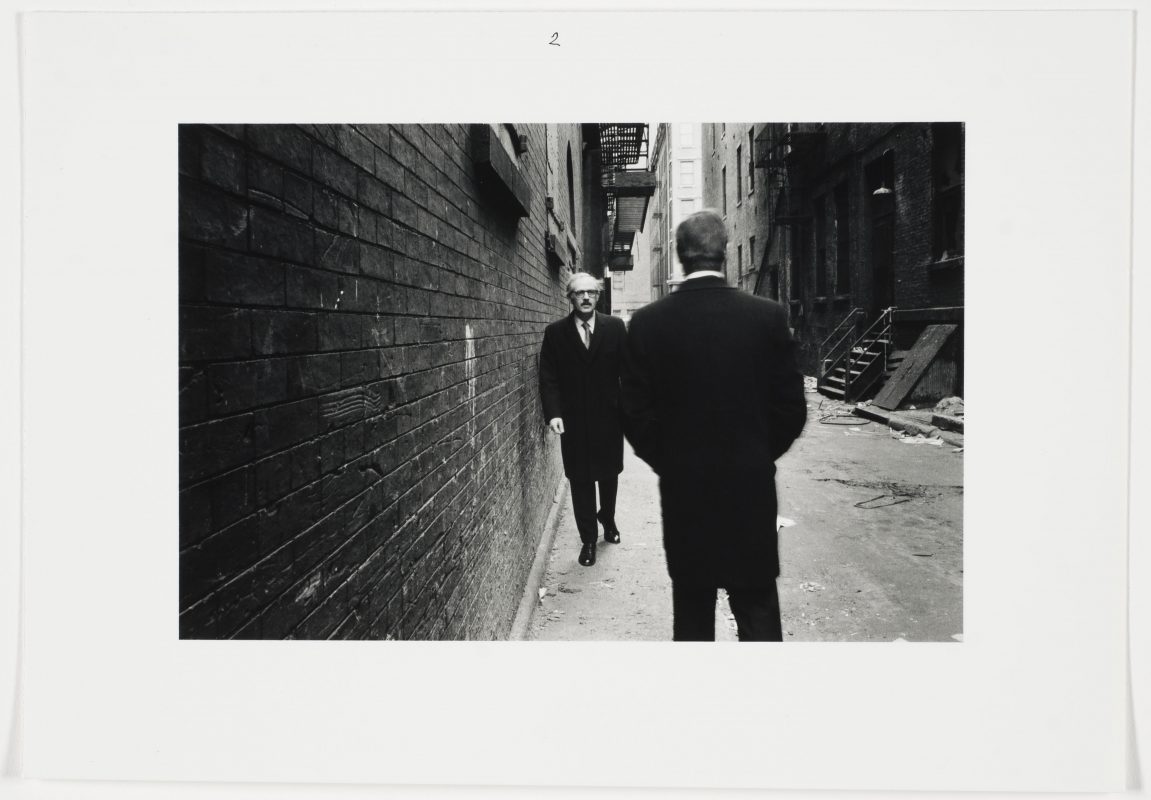

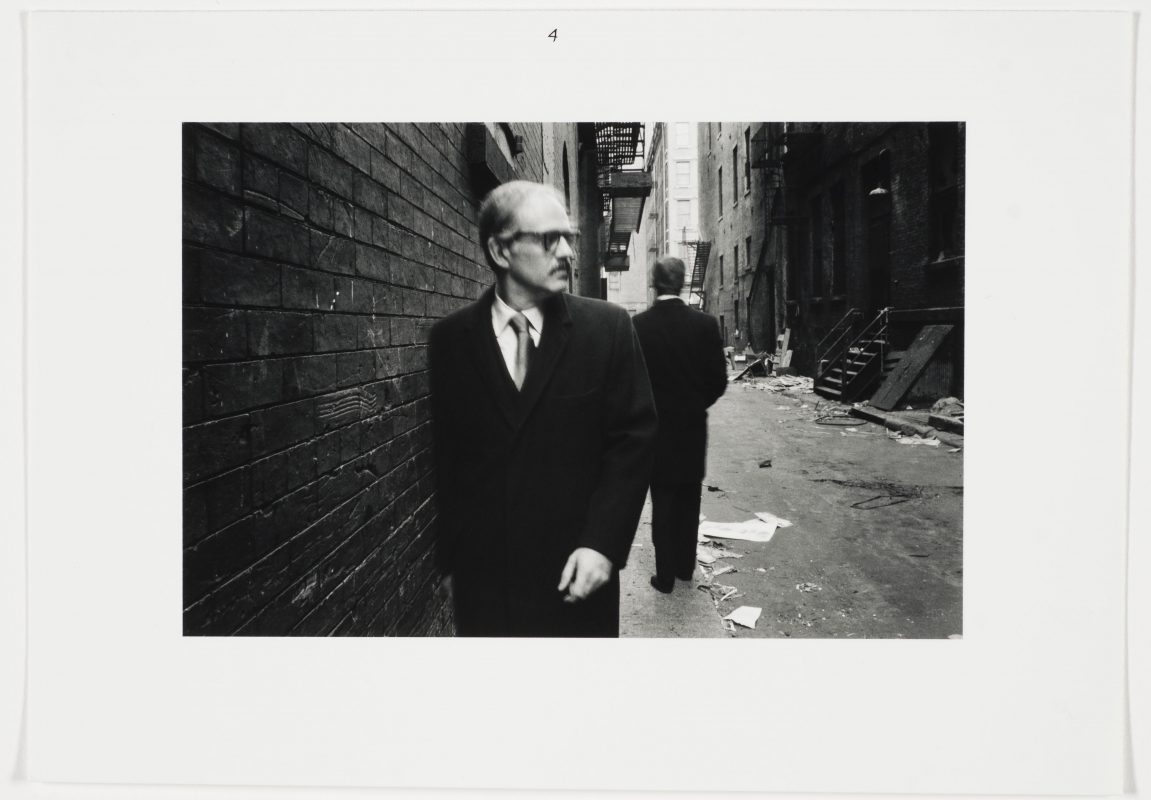

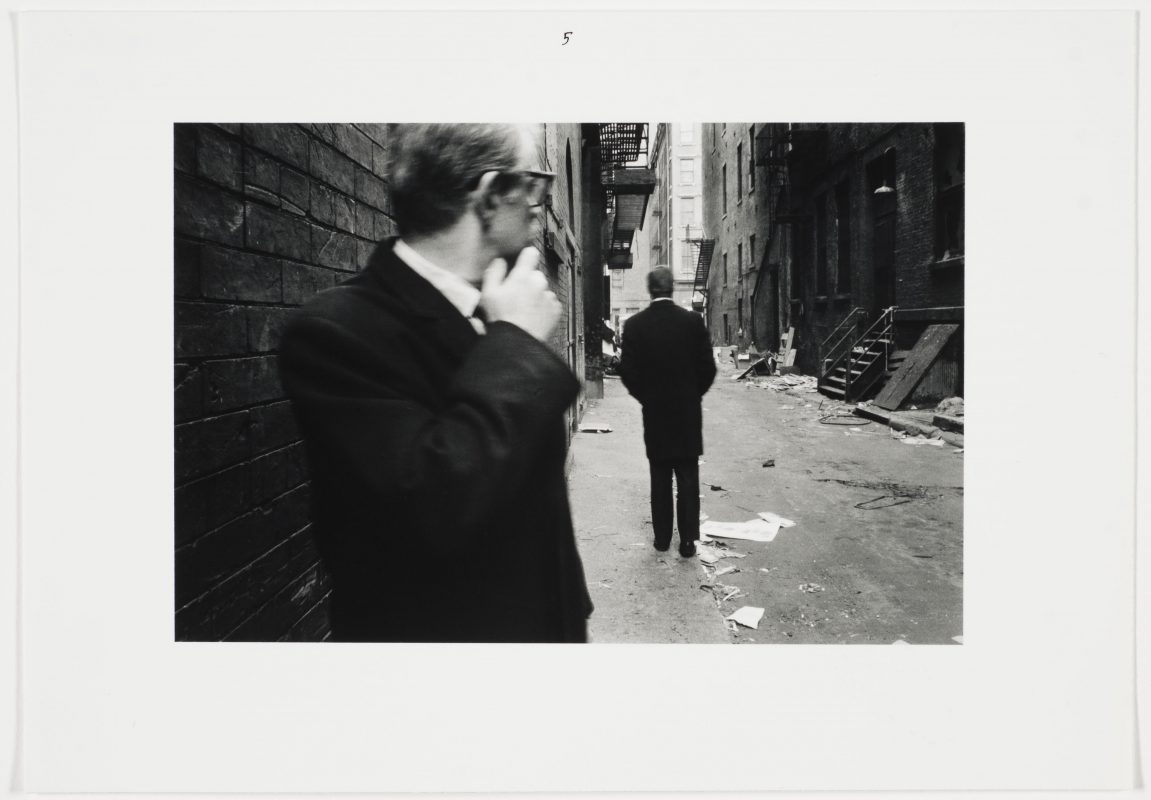

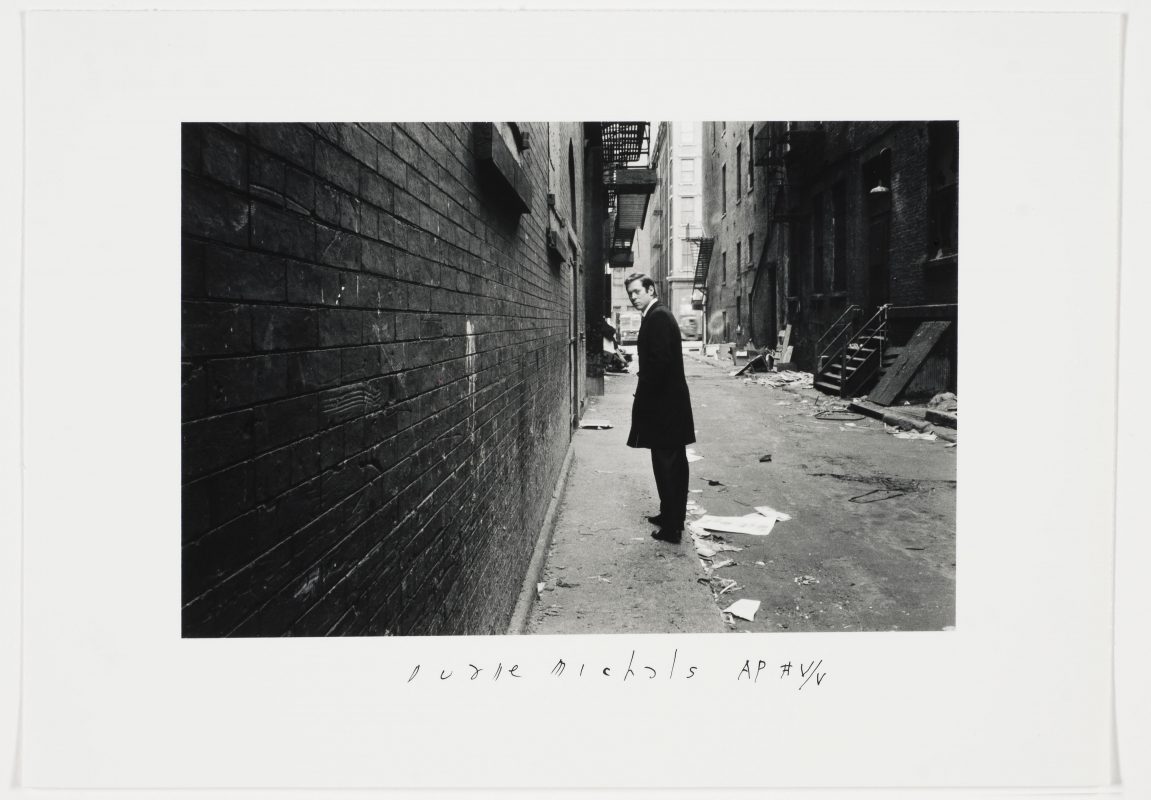

Further on into the exhibition, I was quietly puzzled, though not entirely surprised, by the inclusion of Michals’ sequence Chance Meeting (1970), sandwiched between the religious, literary, and art-historical tableaux of the Victorian era – by the likes of Oscar Rejlander, Julia Margaret Cameron, Lewis Carroll, and William Henry Lake Price – and the more contemporary, cinematic, and suburban constructions of Jeff Wall, Gregory Crewdson, and a number of their recent British successors such as Tom Hunter, Francis Kearney, and Hannah Starkey. Here the caption explained, “Michals uses sequences of photographs to suggest a narrative … two men pass in an alleyway without incident, but the encounter seems loaded with significance … the figures move in and out of the shot, as in a film.” Of course, due to its film-still-like quality, Chance Meeting may on its surface appear to sit within this lineage of fictive, narrative photography. Yet, standing there in the gallery, and having considered Michals’ own misgivings about many of the artists and strategies represented, I couldn’t help feeling that it was an awkward fit. As Mike Regan had recognised in his email to me a few days earlier, the secret to Michals’ work is that, despite its narrative nature, its significance lies not in its promotion of photography’s “artistic value” or in its referencing of the “artifice of contemporary culture”, but instead, in its engagement with something totally experiential and very real: “to see what the eye can’t see”. As Michals explained in 2007, “I’m not interested in what something looks like, I want to know what it feels like.… My reality has entered a realm beyond observation…. Most photographers are always looking at life, they’re looking at surfaces … but unless a photographer transcends appearances … then it’s always going to just be mere description.”

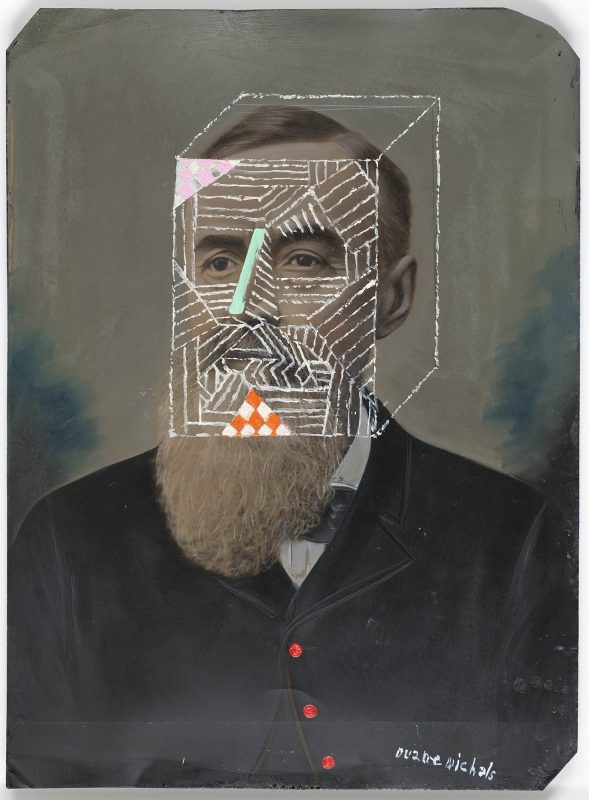

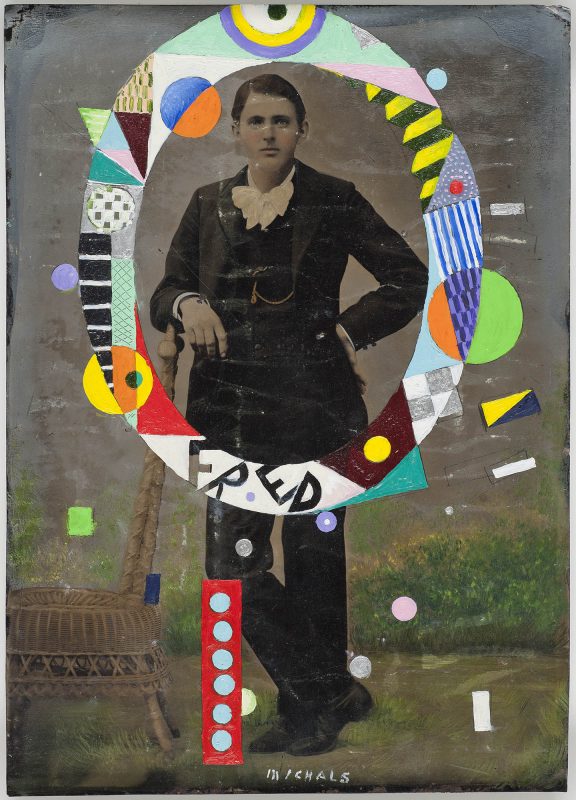

Returning to my desk in the library upstairs, and to the question of how Michals has influenced contemporary practice, I found it tempting to obediently follow the line touted by the exhibition below; to position Michals’ influence within the filmic, the fictive, and the constructed movements that have followed in his wake and make clever comparisons between his work and quintessential examples from this genre. To, for example, juxtapose Chance Meeting with Wall’s famous Mimic (1982), which, on the surface at least, stages a similar sidewalk encounter between two passing men; or to compare Michals’ The Return of the Prodigal Son (1982) with one of any number of Crewdson’s spectacles featuring naked figures standing hunched and ashamed within an otherwise “normal” domestic interior; or even to cite some of Michals’ experiments with collage – such as Olympia (1980) or Collage (The Great Photographers of My Time #1) (1991) – in reference to the current fashion for art- and photo-historical referencing, appropriation, and photomontage, as represented by emerging art photographers such as Matt Lipps, Brendan Fowler, and Anna Ostoya, among many others. Aesthetically, such correlations are hard to resist, and would certainly make the job of illustrating Michals’ longstanding influence very visual, and very obvious. But conceptually, I fear that such comparisons simplify matters and miss the mark, and I suspect that Michals’ impact is a much more subtle affair, embedded within the important lessons he teaches through both his work and his example.

Furthermore, I sense that the lessons to be found in Michals’ work – such as the distinct power of photographic sequencing, soul-searching, sincerity, and storytelling – are today less apparent in the realm of contemporary art, where photography is occasionally invited in order to serve fluctuating trends and ultimately a voracious marketplace, than in the burgeoning photo-book culture and the rapidly evolving context of documentary photography. In these contexts, leading practitioners such as Alec Soth, Paul Graham, and others are twisting, turning, and transforming the relationship between experience and expression in fascinating, and often Michalsian, ways.

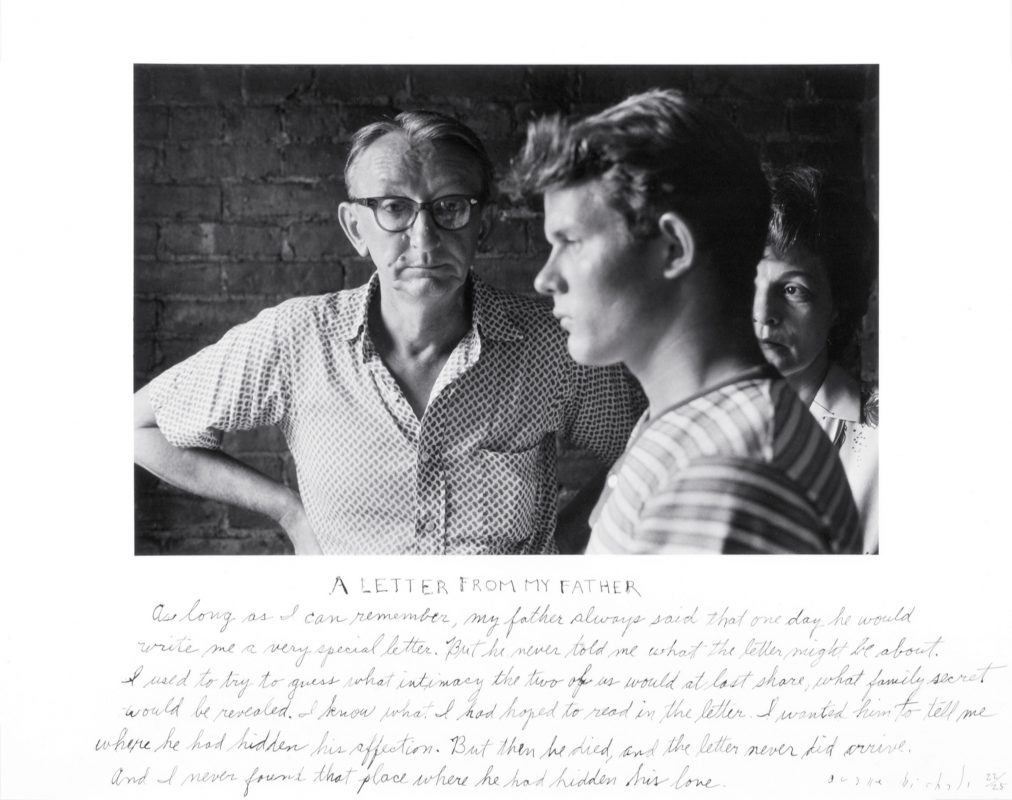

For example, in his highly acclaimed monograph Broken Manual (2010), Soth fuses carefully arranged and sequenced photographs with texts and handwritten notes by Lester B. Morrison (in fact, Soth’s alter ego – again, a strategy torn from the pages Michals) to explore the particular desire to retreat, escape, and ultimately disappear from oneself in a distinctly personal and poetic manner. And in Looking for Love, 1996 (2012), Soth retrospectively delves into his own photographic archive, reexamining photographs that he made in his hometown as an unknown and lovelorn twenty-something photographer more than a decade and a half after they were made; here he consolidates past and present to speak of a lifetime, echoing many of the elements and strategies found Michals’ A Letter from My Father and The House I Once Called Home.

Graham has likewise released two monographs in recent years – a shimmer of possibility (2009) and The Present (2012) – which both embrace the photographic sequence as a means to extend the medium beyond the moment, and use it to explore notions of narrative. They engage with the realm of reality, as Michals described it, “beyond observation.” a shimmer of possibility was originally published as a boxed set of twelve individual books, each containing a short sequence of images and representing small meditations on everyday American life: a man mowing a lawn (Graham’s first foray into the sequential, coincidentally photographed on the outskirts of Pittsburgh in 2004, just a few miles from Michals’ birthplace); a woman crossing the street; some kids playing basketball; an elderly lady collecting her mail from her mailbox, and the like.

In The Present, Graham creates sequences on the streets of New York, but rather than explicitly staging “chance meetings,” he gathers and concocts them from the passing crowds using basic photographic elements such as composition, repetition, depth of field, and the passing of time. With the simple turn of a page, a proud African American businessman morphs into a hunched and bedraggled homeless man; a woman in a dark suit, her hair dyed black, becomes a woman in a cream-coloured suit, her hair dyed white; a man wearing an eye patch transforms into another, similarly blinded, who is forced to wink by the direct sunlight in his eye.

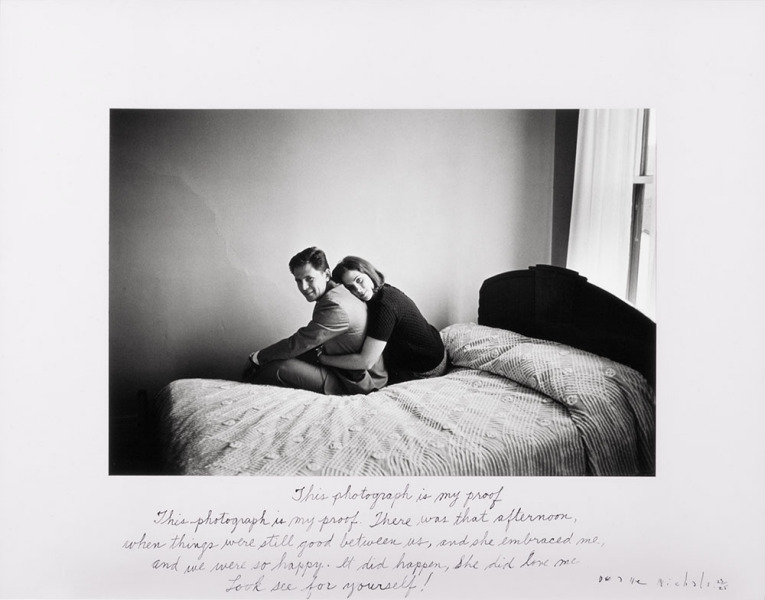

More than in the elaborately staged tableaux and the “open-ended” narratives that reigned supreme within art photography at the turn of the twenty-first century, it is in works, sequences, and gestures such as these – that genuinely explore and encourage the true narrative and storytelling possibilities of photography, that risk accusations of sentimentality in order to establish intimacy and intensity, and that aspire to both discover and express a deeper, more “total experience” – where Michals’ real legacy lies.

After all Michals has argued, “One must redefine photography, as it is necessary to redefine one’s life in terms of one’s own needs.… The key word is expression – not photography, not painting, not writing.… Only you can teach yourself.” For more than half a century, he has helped us discover a myriad of ways to blur boundaries -between photography and art, between fiction and reality, between the personal and the universal, and between the artwork and the artist. But perhaps even more important, he has consistently redefined such boundaries in terms of his own life and his own needs, and has even pushed past such boundaries, repeatedly and resolutely exploring territories well beyond the established frontiers of photography itself. In doing so, he has taught us many lessons; but ultimately he has taught us that we can, and must, teach ourselves.♦

All images courtesy of The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. © Duane Michals

—

Aaron Schuman is an American photographer, writer, editor and curator based in the United Kingdom. He is a senior lecturer at the University of Brighton and the Arts University Bournemouth, and is the founder and editor of the online photography journal, SeeSaw Magazine.