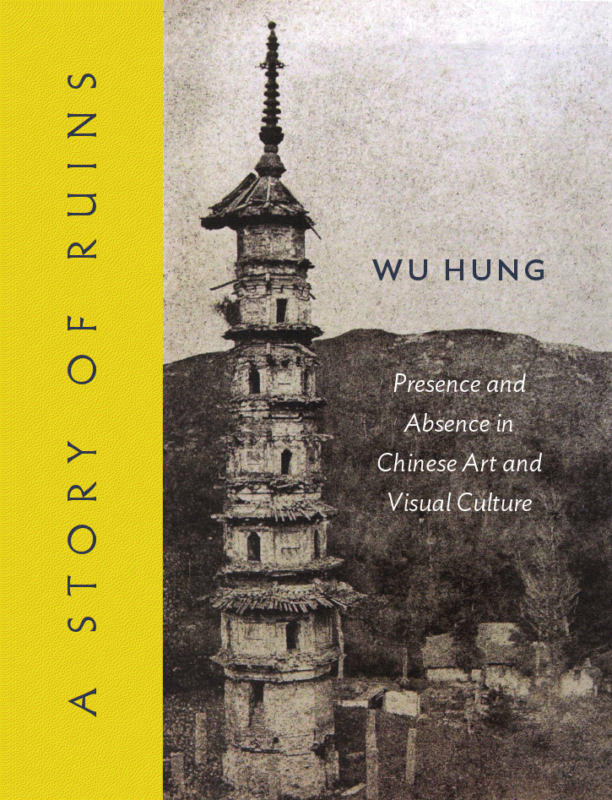

Writer Conversations #10

Tanvi Mishra

Based in New Delhi, India, Tanvi Mishra works with images as a photo editor, curator, and writer. Among her interests are South Asian visual histories, representation within image-making as well as the notion of fiction in photography, particularly in the current political landscape.

Until recently, she was the Creative Director of The Caravan, a journal of politics and culture published out of Delhi. She is part of the photo-editorial team of PIX and works as an independent curator forming part of the curatorial teams of Photo Kathmandu, Delhi Photo Festival as well as the upcoming BredaPhoto Biennial in 2022. She has served on multiple juries, including World Press Photo, Chennai Photo Biennale Photo Awards and the Catchlight Global Fellowship. She has also been a mentor for the Women Photograph programme and is part of the first international advisory committee of World Press Photo.

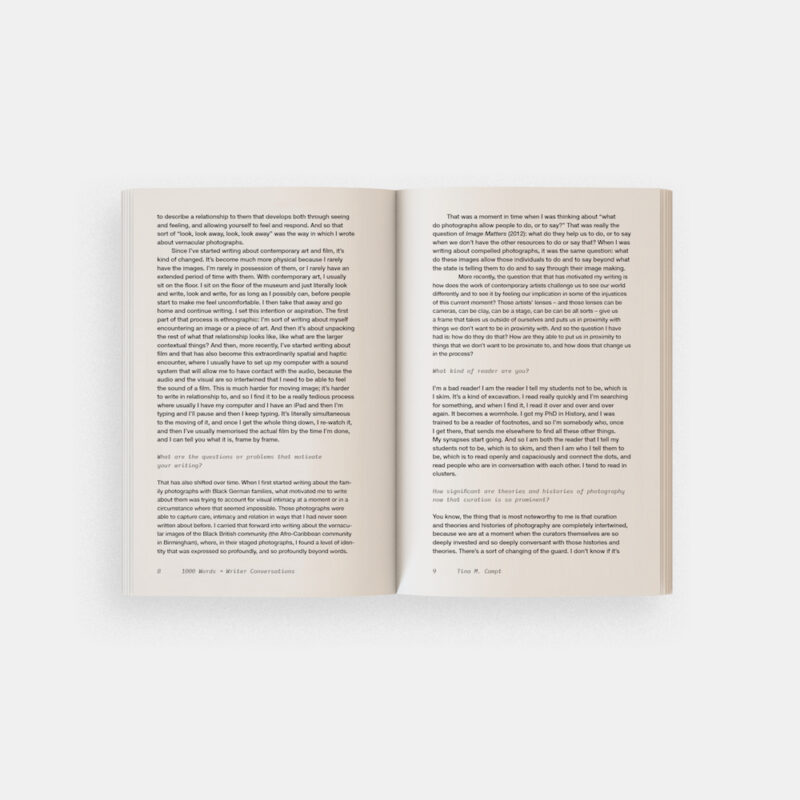

Some of her recent writing includes Viral Images: The role of photography in documenting India’s COVID-19 disaster (The Caravan magazine; 2021); Photography in Crisis: Repurposing the Medium for Solidarity and Action (FOAM Magazine, 2020); The New Era of South Asian Photography Festivals; (Aperture, 2021); Archive as Companion: text accompanying Priya Kambli’s work ‘Buttons for Eyes’ (PIX Vol. 18 Passages; 2022); The Great Upheaval: Can the digital revolution potentially shift the power dynamic in photography? (Viewbook Transformations; 2017). She has also contributed to books including WHY EXHIBIT: Positions on exhibiting photographies (FW: Books, 2018) and exhibition catalogues such as Taxed to the Max (Noordelicht International Photography Festival, 2020).

At what point did you start to write about photographs?

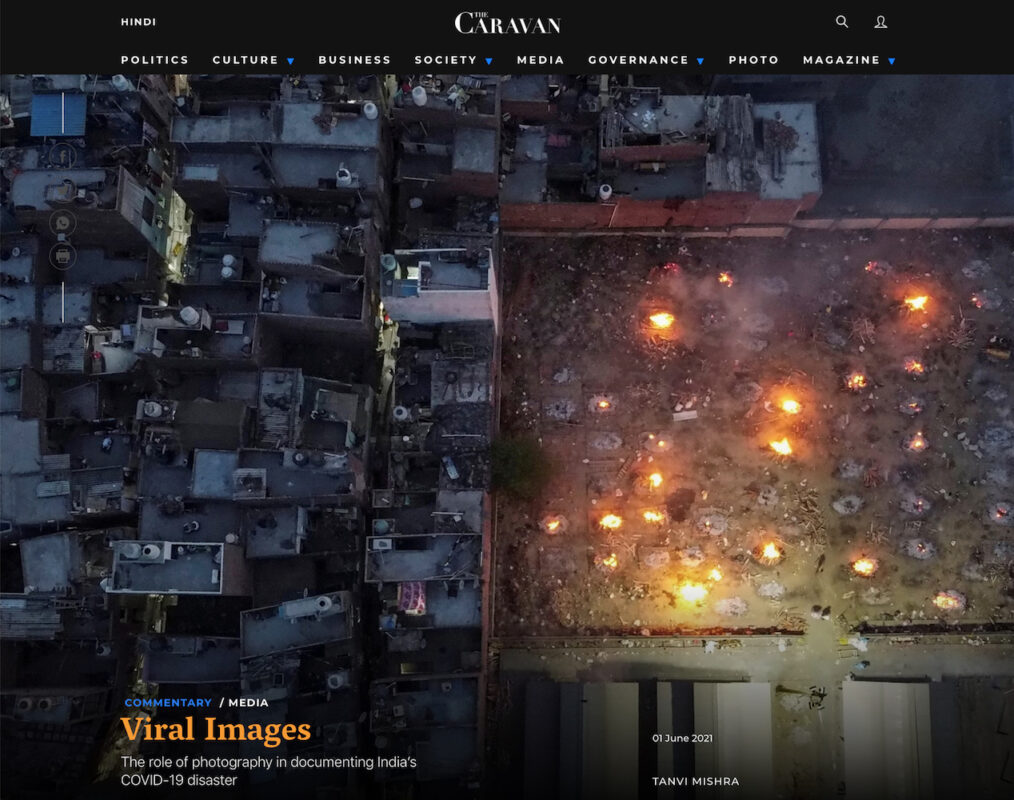

A little more than a decade ago, I was invited to join the team of PIX, an editorial and curatorial practice aimed at building an archive of contemporary photography in South Asia. For the publication, PIX solicits lens-based works, and pairs them with writing that responds to the images. At this point, I was establishing my photographic practice, and negotiating my relationship with the medium. I thought of myself as solely a photographer, and believed that the core of the practice was animated by those who made images. My work at PIX signified my first professional interaction with the work of others, no longer as just a viewer, but as an interlocutor, an editor and a collaborator. The sustained engagement with other makers and their practices played a crucial role in the evolution of my own practice as well. Through this process I was introduced, or rather coerced, into writing.

I have always found it easier to speak with photographs. Through many years of crafting visual stories, initially as a photographer but largely as an editor, I have become, somewhat, attuned to the rhythms of weaving images into compelling narratives. The trajectory of arriving at this point of “ease” has been somewhat predictable, and regularly working the muscle has made the photo-editing process feel more natural. I approached writing with a greater reluctance – my relationship with it continues to be complicated, but it has helped me give shape and voice to the ideas marinating in my mind. In my earliest published piece, for instance, in 2012, in writing about the artists featured in a volume of PIX, I was forced to articulate my photo-editorial choices into words. This was the first time that I crystallised the process of editing images, inherently abstract and intuitive, into concrete sentences. Since then, this connection – between my practice of writing and editing of photographs – has been constantly reinforced, and one has continued to inform and enrich the other.

Over the years, my writing on the work of photographers has ranged from conversational essays to commentary and analytical pieces. As my practice developed, the work that I was commissioned for became more wide-ranging. I was invited to comment on larger questions looming over the visual medium, reflecting on its theoretical and conceptual framework, as well as examining the contours of the industry and the fault lines that continued to plague it. Since I work primarily as an editor of images, these “prompts” that came my way in the form of writing assignments shaped the trajectory of my writing practice.

During my years at The Caravan, a long-form journal of politics and culture, my writing was heavily influenced by the magazine and its editorial process. It is here that the prompts shifted – from premises assigned by others – to my own responses to themes we were engaging with in the newsroom. While my interests are medium-specific, I am drawn now to the intersection of the image with politics, culture and society. In how images circulate within larger publics, and how that affects our ways of being as citizens in this world.

What is your writing process?

My process is often marked by tedium – it can be terribly slow, frustrating and one that mandates constant revision.

I rarely ever write “for myself”, though that is a direction I wish to desperately move towards. Most of my writing is done on a fairly urgent timeline – either in response to a commission or to an unfolding event. My experience in journalism instilled the belief that getting a piece published at the right moment is as crucial to its reception and circulation, as chiselling it to “perfection”. Since writing is the part of my practice, I am least confident and most unsure about, if left to myself, I can continue to endlessly tweak and tighten, in an attempt to reach the best possible conclusion. Even though the lack of time can feel constraining at the time of shaping a piece, it is also an immensely powerful impetus in releasing my writing out into the world. I am learning to get comfortable with the idea that some of the most compelling writing does not necessarily present normative resolutions or answers, but it offers instead, a space to question, stir debate and generate ideas.

The physical act of writing feels burdened with procrastination. I inevitably delay the start till the last possible moment, perhaps because of the potent anxiety I continue to experience on encountering an empty page. However, the process of writing begins much earlier. In the days leading up to putting words to paper (or a Word document!), I make my way through the premise and arguments in response to the prompt. A lot of this thinking happens in the unlikeliest of places – on a walk, in the shower, while cooking – and rarely at my work desk. On the days when I am actually writing, I am fairly chaotic. I have many books and multiple tabs open, because I comb through references fairly extensively. Most of these are texts I have read before, and that have offered insights that resonate with the idea I am working through. Other sources of inspiration tend to be authors or thinkers whose words help me when I arrive at an impasse. I find myself to be both heavily distracted, fielding multiple influences at the same time and intensely concentrated, in that I cannot pursue any other intellectual task during those days.

My writing process is quite similar to my photo-editing practice: with a large set of images for instance, the beginning can often feel quite scattered, and the ideas and arguments fairly disconnected. It is somewhere at the half-way mark of the process that the links and connections begin to emerge in the loose structure, revealing a possible outcome where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Sometimes, the emergence of this clarity can hasten the process, and the remaining puzzle is solved at an accelerated pace. Just as with an edit on images, writing benefits with some resting time, allowing the words to sit next to each other, revealing meanings that were perhaps not as visible the first time around.

I wonder if you might expand on the “prompt” as you describe it: it seems to be a catalyst and a beginning, of course, but I wonder if in some ways, it is also for you a sign of writing’s contingency, something which describes how, as a writer, you are always in dialogue from the very beginning. Does your attention to the “prompt” describe something of your writing practice and your attention to writings relationships?

I see the “prompt” as an impetus, one that pushes me to act. Those of us who choose to think of ourselves as political beings respond to change in our environment. Our craft is one way to channel this response.

The dialogue you speak of is ongoing, and inevitable. We use the tools we have at hand to articulate our concerns. For me, writing may fill in for the inadequacies, or limitations for response, within photography, or it may be used to activate different audiences.

I consider myself fortunate to be able to engage with the image in varied forms. This engagement is what I see as the dialogue – at times collaborating with image-makers, their work and archives and in other instances, using writing as a possible instrument of inquiry. I find this response to be contingent, and writing as one form of that contingency.

What are the questions or problems that motivate your writing?

Most of what motivates my writing is what motivates my work with images. These concerns shift with time, in response to unfolding events and my evolving personal politics. I see writing as a way to distil the varied questions and ideas that emerge during my primary practice of working as a photo editor and curator.

Currently, one of the biggest questions I am wrestling with in photography is to do with the process by which images make their way into the world, and the manner in which their circulation shapes discourse – within the image economy, but particularly outside it, in society. I am interested in how the surplus of imagery affects our psychological being and how the consumption of these images moulds our reception to social, political or cultural realities.

Having worked in journalism, particularly on the photo and multimedia desks, I have witnessed the impacts of such circulation first hand. The choices we made had the potential to shape public opinion. This was both a potent instrument, as well as a heavy responsibility. While it may sound staid as a concept in the space of photo discourse, I am interested in the image as evidence in today’s media landscape. Where does such evidence hold value, when courts themselves look away? How is media, and the narratives it is composed of, used as information warfare, both by those in power and those opposing it? How does the image need to be packaged to be consumed as truth or propaganda? How do we read political photographic fiction in today’s image world? How do we decide to trust a certain image, or the sources it is disseminated through, and what governs this psychological response? When does image circulation, particularly on social media, trigger a near immediate reaction, whether by the general public or by organised troll armies? It is this response that I’m interested in examining: is it genuine or manufactured; how does it measure “truth”; how do these images change in their meaning as they further circulate in the digital realm?

Another concern that consumes much of my thinking is around the politics of representation – specifically, whether it is possible to ever circumvent the hierarchies and power dynamics embedded within photography. While, earlier, I was curious about how the “democratisation” of the medium impacted this balance, I am no longer as interested in the pervasiveness of and access to the medium, but more so in where this conversation around representation – “who gets to tell whose story” – leads us. The push towards local and “insider” narratives is one that is now, rightfully so, valued. This reorientation is the long-due reparation of the historically skewed representation of many communities and issues, which was a direct outcome of the privilege of either the coloniser’s lens or the “outsider’s” festishistic gaze.

However, I question the notion of this “insider” and how we arrive at its definition. Is there an ideal insider? Is she always best positioned to tell that story? Aren’t we all insiders, truly, only to our own stories? And yet, autobiographical narratives are only a part of how we learn about the world, and how we choose to produce or consume media. Lived experience is a crucial component, in that it brings to the fore a gaze that is less essentialist than what has existed largely in narrative storytelling. We are, often, better placed to access communities or issues that we have engaged with otherwise, outside of the “professional” demand; those that we resonate or connect with as individuals or citizens, not necessarily only when tasked with representing them. Does this mean that there is a possibility for an honest engagement, that may well be “imperfect”, with a narrative outside of the lived-experience paradigm? Is authentic storytelling a function of provenance? Is identity an absolute construct, or does it shift in response to the subject and landscape? I am interested in how the intersection of various markers like gender, caste, class, region, religion as well as traits such as lived experience and personal politics guide the making of this definition, complicate notions of identity and affect the proposition of narratives distinct from historically dominant perspectives. These intersections often guide the choices of artists I write about, and that writing is an important conduit that enables the development of my own understanding of the concerns regarding authorship and narrativising.

Recently, I have been interested in reflecting on the positionality of image-makers, and how their own identity impacts the work they put out into the world. The term “identity” here is not to be seen as synonymous with nationalistic definitions – defined by borders and passports – but more by their position as citizens in the world social order, and in relation to the narratives they construct. Whether it is even possible for works to reckon with aspects of the makers’ identities and if so, whether photographic works are as much about the authors as they are about those who are photographed?

Within this realm lies one of my biggest concerns of late – photography’s inability, or limited ability, to shift the gaze towards the perpetrator, the oppressor, the coloniser. These definitions are not in relation to the conventional binaries of the West/East, urban/rural etc., but with reference to where the author of a work is placed when she is representing someone other than herself. While contemporary discourse has compelled narratives to shift, from unidimensional perspectives of suffering and impact, to include a broader spectrum of human emotion and experience, photography has been limited in visualising those other than the victims or survivors. There has been an inherent difficulty in exhibiting structures of supremacy, of complicity.

My own position as a dominant caste individual from India makes this particularly pertinent for me. The need to pass the lens, and so the power, into the hands of the oppressed and marginalised to build their own narratives – of both joy and suffering – to self-represent their own communities is urgent. But, alongside, authors, especially from majoritarian or dominant identities, need to apply a more critical gaze to their own communities – those, for instance, that have historically oppressed others by way of privilege afforded by the caste system, a discriminatory social order of hierarchy prevalent across the subcontinent. The capacity of visual narratives to critique these systems of power, and not merely display them as “documentation”, is rare in our image world. I am interested in these limitations and in examining whether photography truly has the ability to upend historical narratives, which have inevitably been authored by the very dominant systems and lenses it has failed to effectively illustrate.

Apart from these conceptual interests, a lot of my writing is motivated by visual works emanating from South Asia, particularly when their vocabularies are distinct from mainstream photographic canons. Since most references within photography are from Western histories and contexts, I am drawn to artists and works that attempt to break this trajectory in form and language. I usually engage with the artists in an editorial or curatorial capacity, and the writing emerges from these collaborations.

Your description of the image as evidence feels important, in that it gives an equal weight to how the image is made and also put to use, how it acts and impacts, alongside what it shows. Do you think this process of exploring positionalities leads us in some ways towards images being understood as assemblages, and truth as something that cannot be reduced down to one essentialising characteristic?

The relationship between the photograph and “truth” has been a complicated one. Ambiguous by nature, the image has always been open to a subjective interpretation, even in its use as a document. As an editor, I particularly appreciate the transformation of an image and its meaning, when it interacts with another image, or with text; how it is re-casted depending on where it is placed, how it is disseminated and so on. The notion of “truth” has always been defined by multiple forces, at times by a collection of images, at times by other interactions and factors. What an assemblage may do, particularly in the case of evidentiary images, is to make a particular truth harder to deny. While an “iconic image”, a term I find to be redundant now, may evince a particular truth about a situation by a singular author, the streams of images generated may help reiterate its evidentiary value.

However, as I write this, I find exceptions emerge to this proposition. Take the recent pull-out of the US from Afghanistan or the current war in Ukraine. What we see, despite the surfeit of images generated, is largely a singular perspective. A singular truth? The collections that emerge are predominantly authored by Western image-makers, or for Western publications. This repetition leads to a redundancy, with most photographers creating work that reaches the same conclusion. Rarely do we come across the deployment of the image in critiquing the systems that led to these conflicts, to look at the complicity of Western nations and modern-day cycles of imperialism.

In the case of positionalities, I am not so concerned with this notion of “truth” but more with the aspect of authenticity, of honesty. Exploring an author’s position in their work helps us parse through their motivations. Self-reflexivity can serve as an anchor, from which we construct our truths and reveal why we reach the conclusions we do.

What kind of reader are you?

Sporadic and unstructured. I now read mostly for work, which fortunately for me is around themes that genuinely interest me and enrich both my writing and image editing. Much of it is triggered through prompts – figuring my way through a writing invitation, working through an edit or deconstructing a premise someone may have posed. Often, reading offers me an articulation of a politics that I find difficult to put into words myself.

During my tenure at The Caravan, my role required extended reading from a wide spectrum of contributors spanning a range of topics. A lot of my writing education has been from observing their first drafts take shape into finessed final pieces. I was privy to the writer-editor dynamic and the tense tug of the relationship. I would pore over the comments from editors to the writers, and witness the evolution of these drafts, as they were refined over time, through intervention and exchange.

I always have a list of pending readings – which seems to grow at a much faster pace than the rate at which I consume them – and I’m constantly dreaming of a reading residency that may give me the time to catch up!

How significant are theories and histories of photography now that curation is so prominent?

My engagement with the medium began as an image-maker. While my role may have changed significantly over the years, my understanding of photography is largely shaped through a practitioner’s lens. I have never had any formal training in photographic education, and theory has never been a core component of my work with images.

That being said, I do consume some theoretical texts, particularly those that break away from being dense and opaque – the most common obstacle of this genre of writing. I do wrestle with the codification that theory brings with it, particularly for culture, and a medium as inherently ambiguous as photography. I have regard for theory and academia, for its rigour of thought and deep, sustained engagement. However, I am interested in working at the cusp of academia and practice. For this, theory needs to be activated into accessible forms and for academics to invest in dissemination across channels beyond their own structures. To quote from scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore: ‘to think theoretically, but speak practically.’ I am drawn to artists/practitioners who comment on or respond to theory in their works, building additional channels of circulation and deconstruction.

As for histories of photography, I consume them to keep pace and build context to certain discussions or texts I come across. However, I approach these with some degree of caution, given that no history is definitive and mainstream versions have, largely, been authored by dominant perspectives. I am also constantly trying to strengthen these muscles of criticality, in order to allow an evolution of these definitions of who/what constitutes a dominant/mainstream or oppressed/fringe perspective, and that these can shift depending on relational dynamics. Largely, histories of photography – inevitably mimicking social histories – are rooted in Western canons and colonial perspectives. While they help build structures to understand one linear progression of the medium, they carry with them significant erasures, by missing out on or misrepresenting large populations and perspectives. I do advocate that some of them be read so as to have a framing, from which to subvert. Ariella Aisha Azoullay’s recent publication Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (2019) is one such proposition for subversion, offering the possibility of an alternate reading of photography through historical time. Tina M. Campt’s Listening to Images (2017) proposes using sound and haptics as a register to re-read images that have historically carried different meanings. I also consider micro-histories or personal histories as potent historical documents, if collated and contextualised within a historical timeline.

Then, it is predictable that my personal view of curation is not dependant on theories and histories of photography. I have always found them to be separate fields, that at some points may collide or intersect, and at others may run parallel or even be entirely removed from one another. I think the choice depends on the curator and/or the institution, depending on how they perceive a “valid” curatorial practice.

I consider curation to be as open-ended as an artist’s practice – some may interpret it through a reliance on pedagogy, others may be influenced by theory without deploying it consciously in the building of work and even others may entirely reject it, dismissing it as didactic to build a curatorial premise on an entirely different tenor.

So, to answer the question, I don’t find the link between theory, histories and curation to always be very direct or consistent to comment on how the supposed amplification of one impacts the other.

What qualities do you admire in other writers?

Accessibility, and the ability to weave complex ideas into simple sentences.

Brevity, precision, and narrative clarity.

An ability to be self-reflexive.

Personality, colour and texture in writing without deploying complicated language or purple prose.

What texts have influenced you the most?

I don’t think I can name texts, because I associate more with authors and their trajectories of thought, than a particular iteration. It is simpler for me to list writers who have had some form of influence or provided inspiration, either to my politics or my practice. The connection is as intuitive as the one between multiple images during an editing exercise.

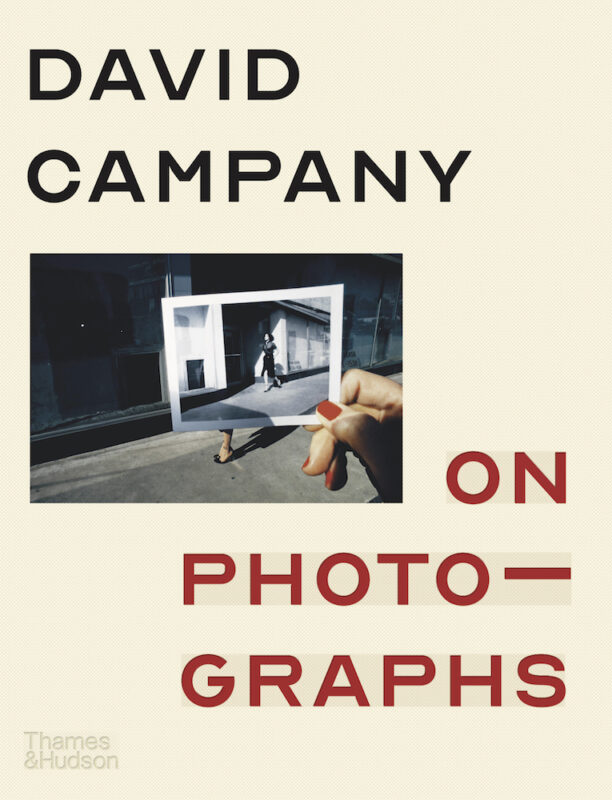

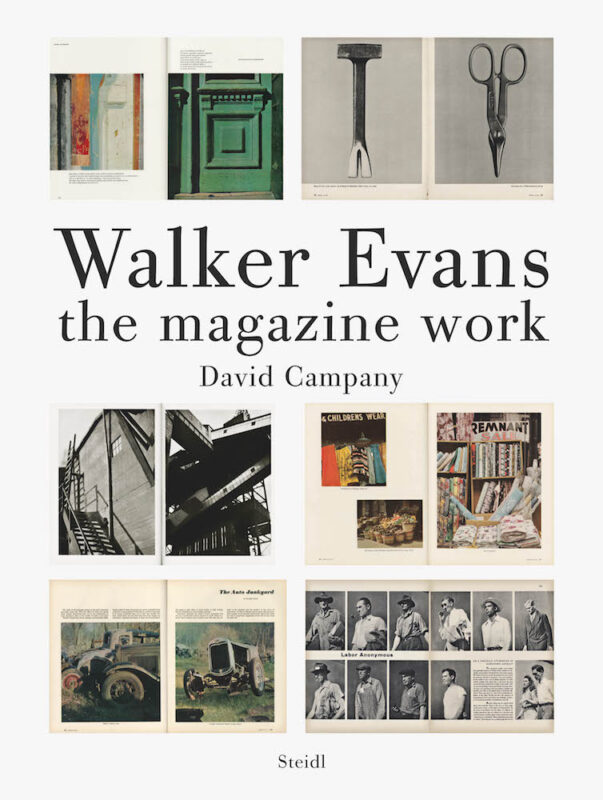

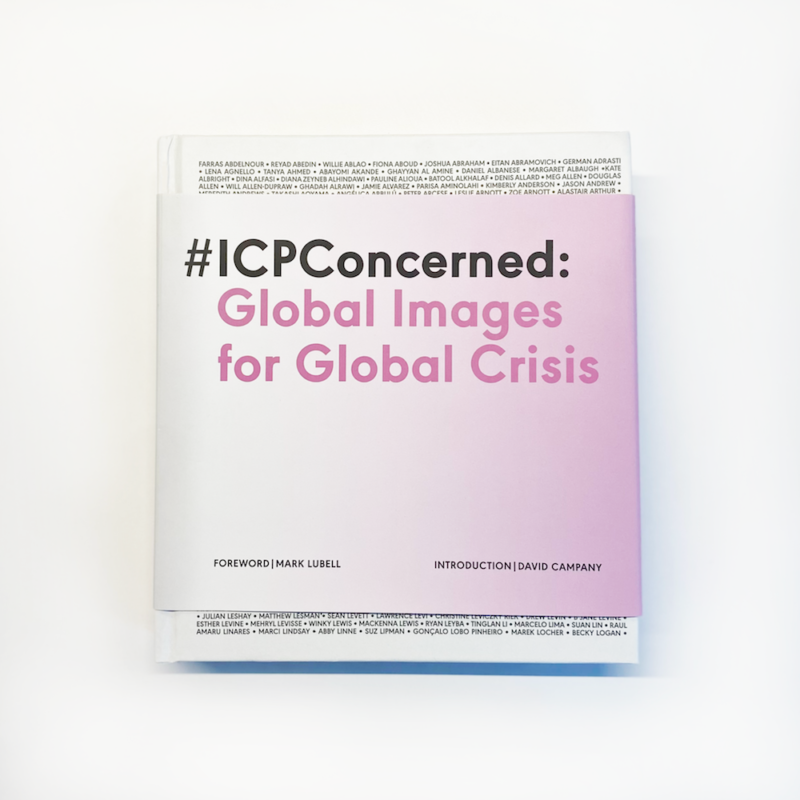

Listing them in no particular order: Tina M. Campt, Ariella Aisha Azoullay, Mark Sealy, B. R. Ambedkar, Frantz Fanon, Kajri Jain, Maaza Mengiste, Teju Cole, Alana Hunt, David Campany, bell hooks, Amitava Kumar, Aveek Sen, Allan Sekula, Stuart Hall, Gayatri Gopinath, Audrey Lorde, Joan Didion, Joan Fontcuberta, Eyal Weizman.

What is the place of criticality in photography writing now?

Significant.

I do think that many texts in photography, are about images or descriptive writing. A lot of my own writing also falls within this definition, particularly when I am focusing on a specific artist’s practice. While I am in favour of using writing to deconstruct image-making for a general public, and offer them a vocabulary with which to enter the work, I do not believe that a text must decode or lay bare the entire work to the audience. This would be an injustice to the image, to rob it of the ambiguity that makes it universal, in the way in which it connects to each individual.

Critical writing, however, allows an engagement that has the potential to “expand out of” the artists’ practice, using it as a trigger to deconstruct an imposed premise or to weigh it against its own claims. It could also be used as a springboard to speak about larger themes – the image as a sociological study, or more formal, medium-centric concerns. I imagine the act of critical writing to be radical, one that can activate the political imagination. It helps us envision alternate readings and possibilities within a work. Unfortunately, criticality is often seen as an effort to diminish or “cancel” works, and not as a channel to foster debate.

What if criticality were built around the politics of care? For me, this would embody an accountability to our fellow citizens, not just those who are in the role of spectators and subjects, but also to our industry peers, as image-makers and thinkers. This “care” could be embodied in thinking about and building images, reflecting rigorously on how we see and what or whom we show, demanding more out of the practice and building a collective conscience towards questioning the conclusions we reach (or don’t) with photographic narratives. In my practice, since I work mostly with images that are inevitably oriented towards the human experience and society, rather than form-based or conceptual experiments, these concerns have reverberations beyond our own industry.

This grounding in care could be a potent ingredient for criticality – in so much as we view it as collective learning, and as an instrument to dismantle the hierarchies that may emerge in the process. The critic, the image-author, the viewer as well as the practice itself stand to be enriched if we were to build systems that nurture criticality as well as the response to it. While there is no dearth of critical thinking, there are very few platforms that champion this kind of writing. Perhaps for criticality to thrive, it needs to exist outside of a capitalist structure, seen more through a discursive lens as an intellectual pursuit.

Perhaps this existing outside of capitalist structure brings us back to your desire to write for yourself? Have you found tactics for writing which allow you to construct a space where writing functions in its own or in your own time?

What I mean by existing outside of a capitalist structure is that knowledge production cannot be beholden to profit. However, it requires institutional support to sustain itself, functioning akin to the academy but allowing a more fluid exchange with those outside of it. Those that have resources could (should?) divert them to this end, investing in a return far greater than any financial gain.

What stops me from writing for myself is time. The kind of writing I currently pursue does not pay commensurate to the labour it involves. For most of us, we are already functioning outside of this realm of profit-making, and the desire to write stems from a need to respond and engage. If support was extended to foster deeper engagement and thought, it could help in wrestling time away from other pursuits, and to move away from the need to constantly “produce”.

Before I embark on the process of writing for myself, I need to drown out the noise, and listen. To “take in” more than I “put out in the world”. Reading is a necessary precursor and an integral part of this process. For years, I have felt, that as grateful as I am for the writing invitations, I am compelled to respond immediately. While this works a different muscle, writing for myself involves a longer, more sustained engagement with a theme, one that perhaps assimilates many of my influences and experiences.

So the answer to your question is no, I haven’t managed to construct this space, but I am hopeful that it will emerge as my practice evolves, or when someone reading this is compelled to help create it!♦

Further interviews in the Writer Conversations series can be read here

Click here to order your copy of the book

—

Writer Conversations is edited by Lucy Soutter (University of Westminster) and Duncan Wooldridge (Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London), upon the invitation of Tim Clark (1000 Words and The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University).

Images:

1-Tanvi Mishra © Aditya Kapoor

2-Opening spread of Viral Images, an essay on the role of photography in reporting on COVID-19, first published in The Caravan

3- Issues of PIX since 2011. PIX is a South Asian publication and display practice looking to archive contemporary photography in the region. Over the last ten years, PIX volumes have addressed various thematics and also produced country specific works on photography from Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Myanmar, Nepal and Sri Lanka

4-Opening spread of The Great Upheaval, an essay on the impact of the digital revolution on photography and whether it has the capacity to shift the power dynamic in photography. The piece was published in Transformations, Exploring Changes in and Around Photography, a project to explore changes and support photography in a digitally connected world