Richard Mosse

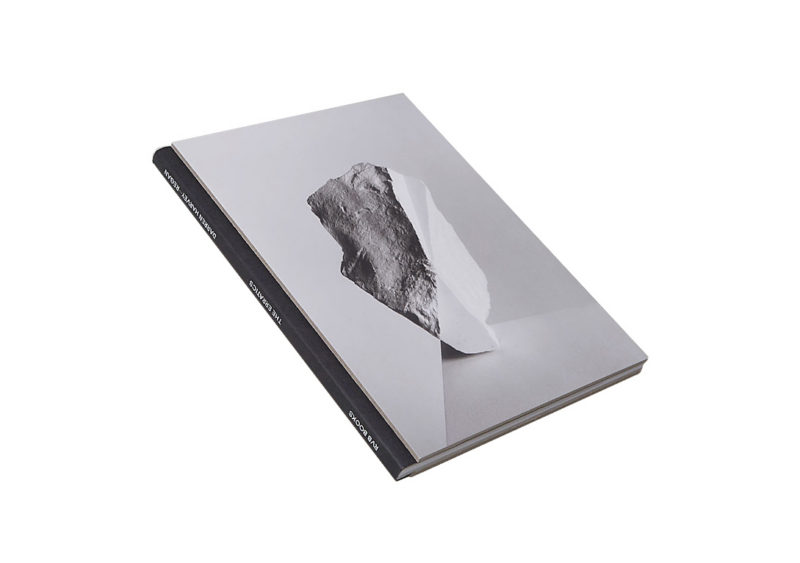

Incoming

Essay by Duncan Wooldridge

Judith Butler, in her book Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? poses an important question: “What is our responsibility toward those we do not know, toward those who seem to test our sense of belonging or to defy available norms of likeness?” How, Butler asks, are we to respond when we encounter a condition beyond our own life experience? What is our responsibility?

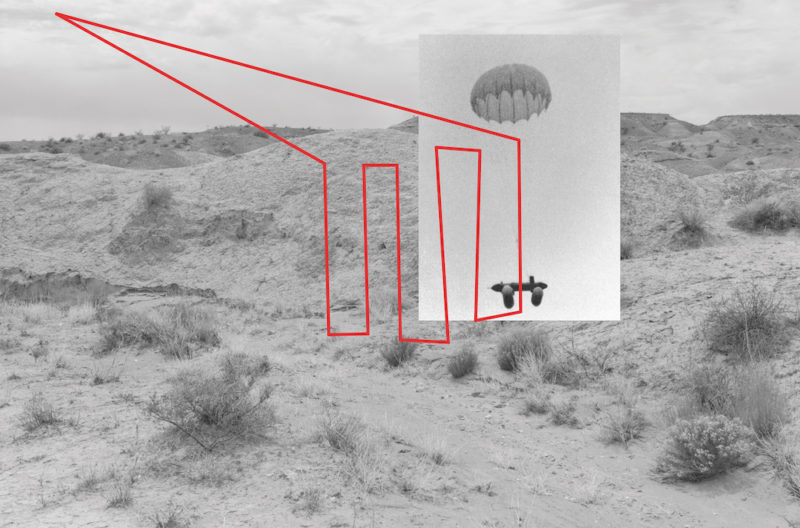

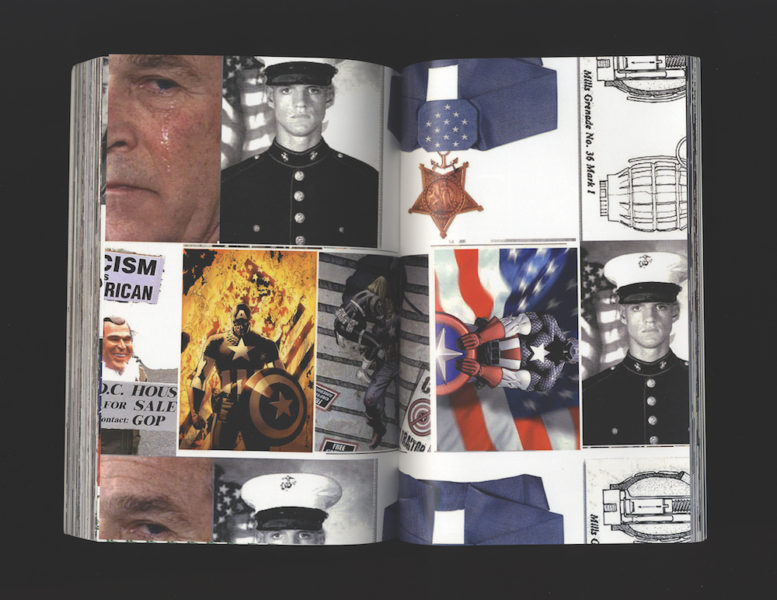

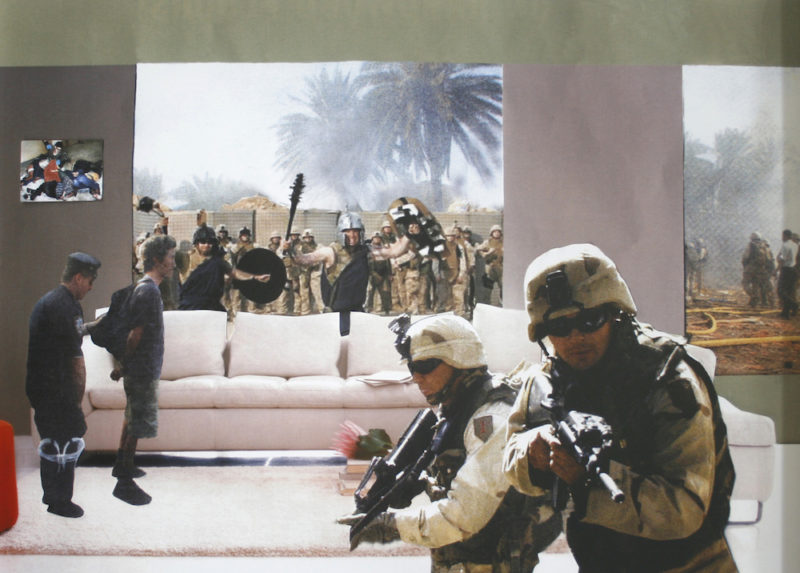

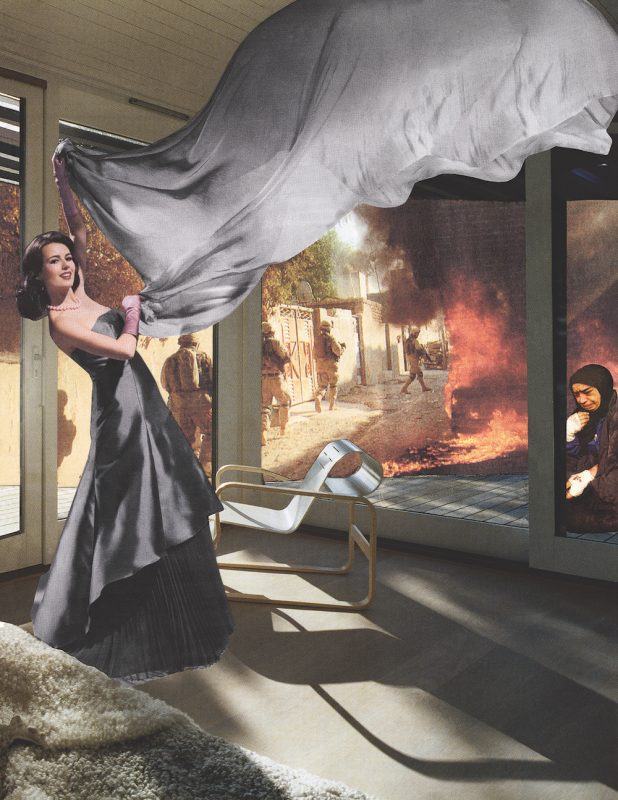

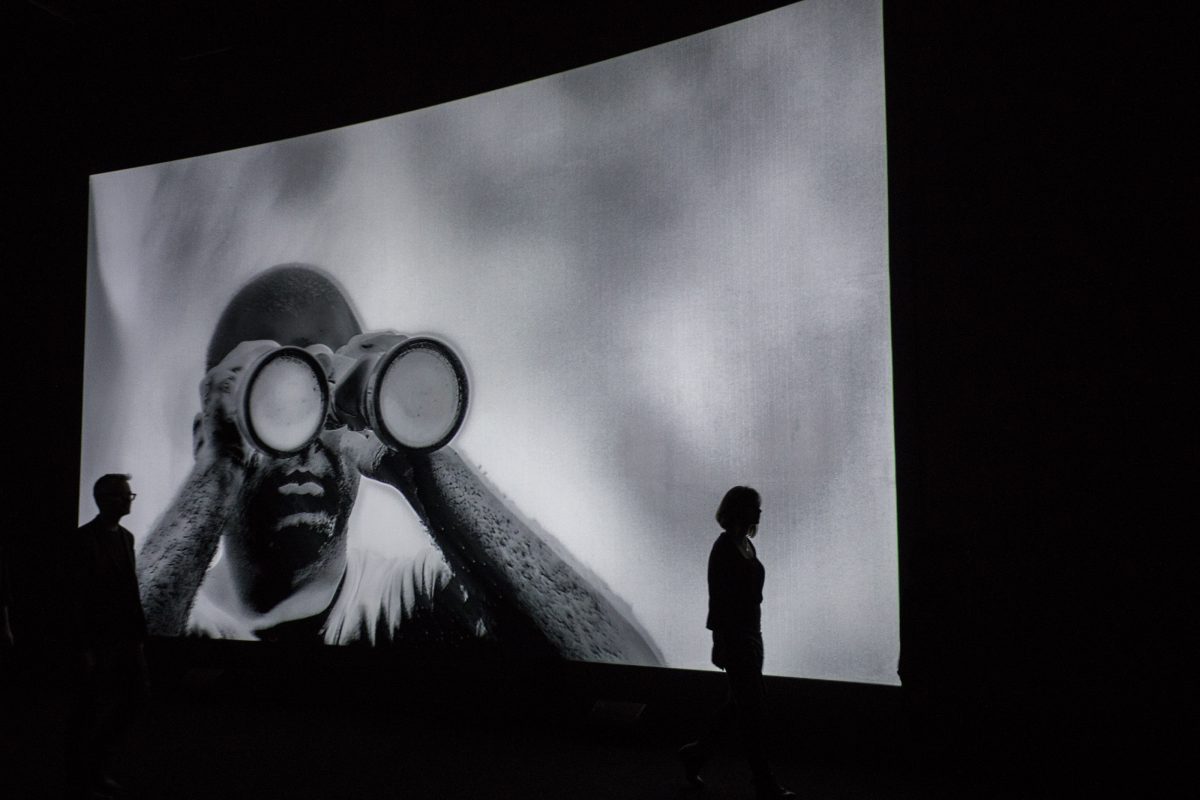

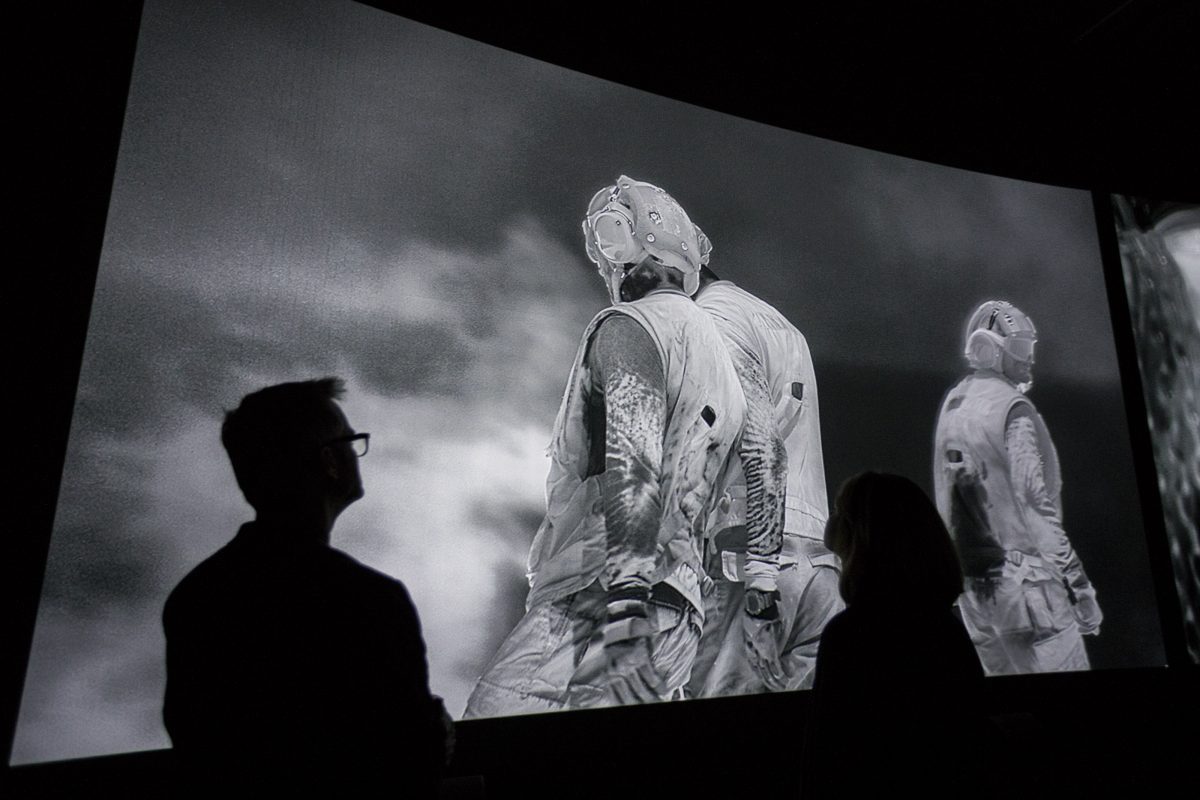

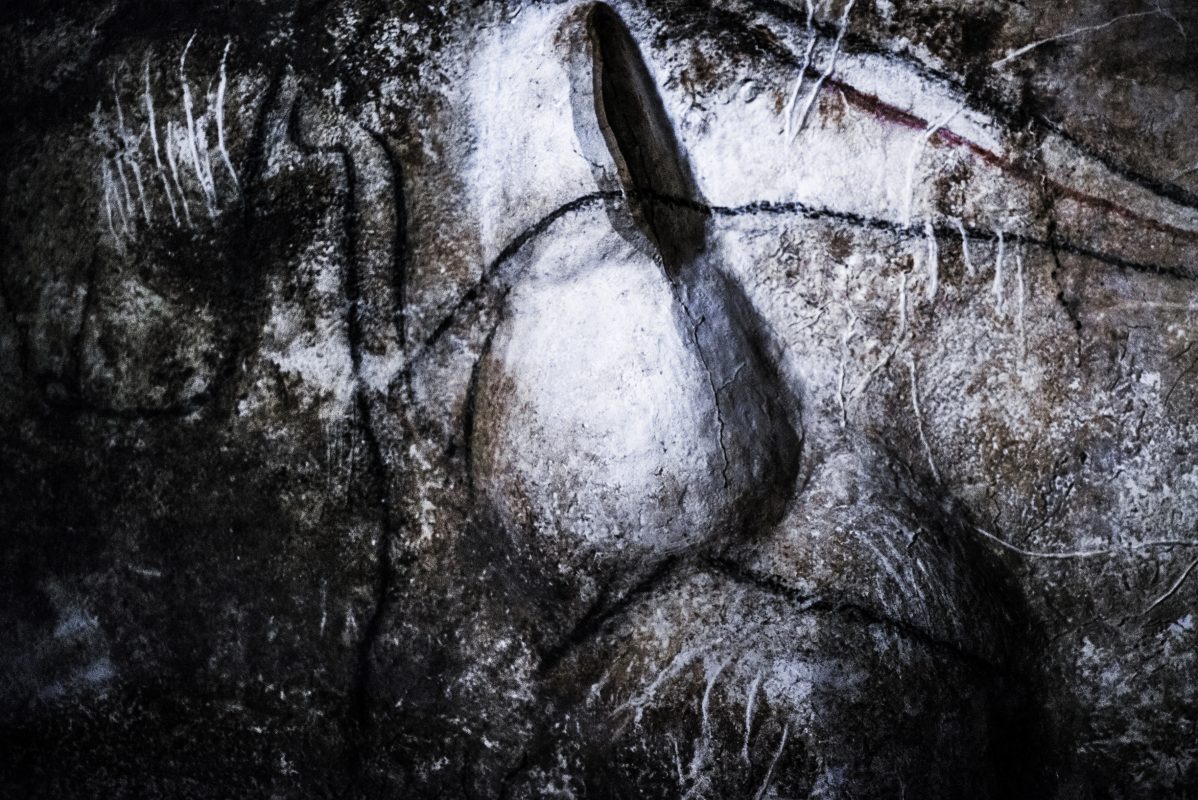

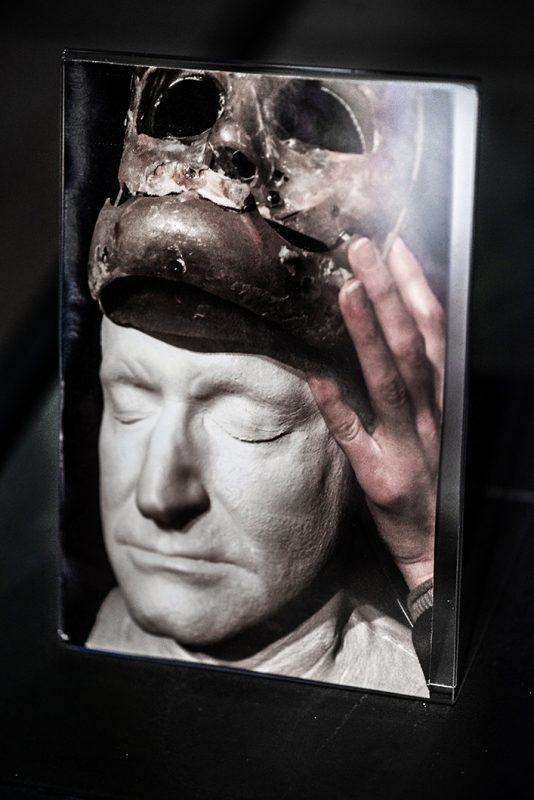

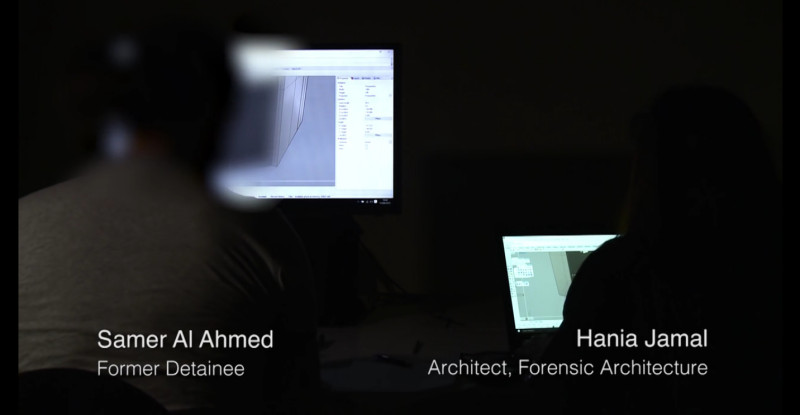

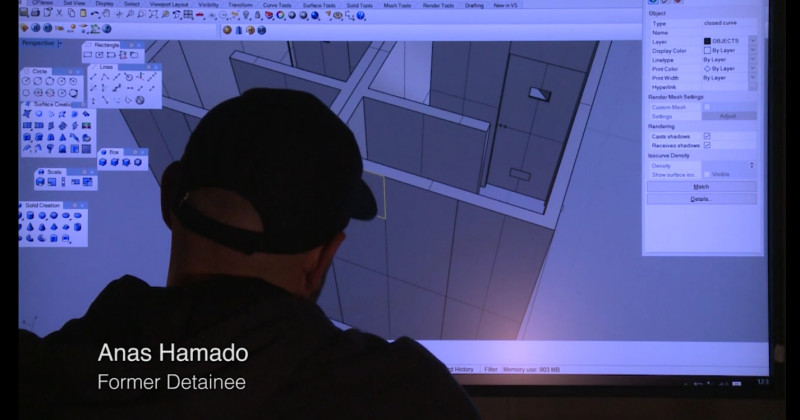

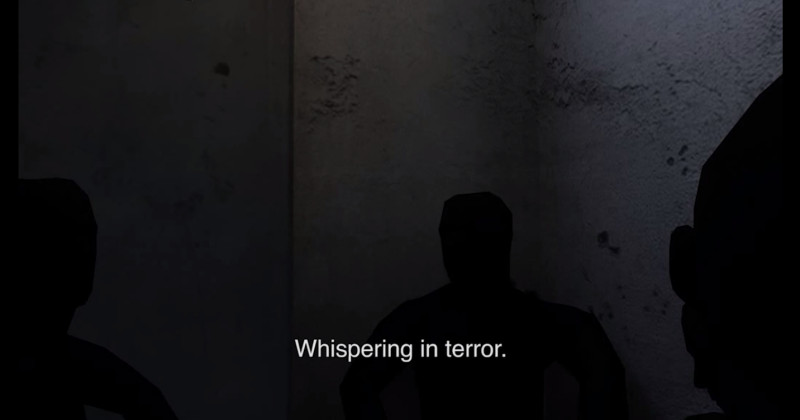

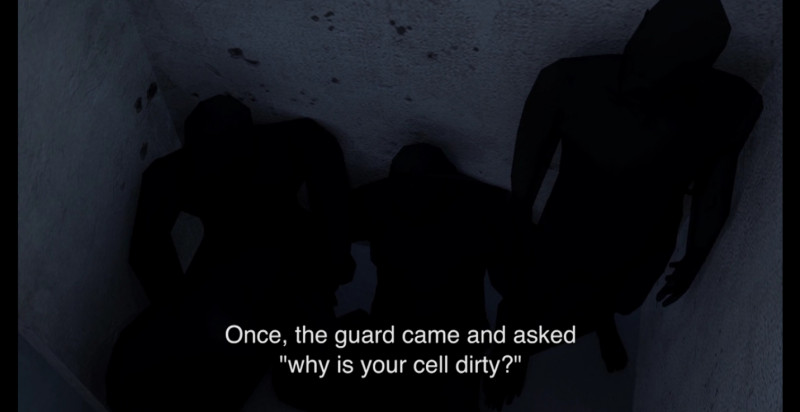

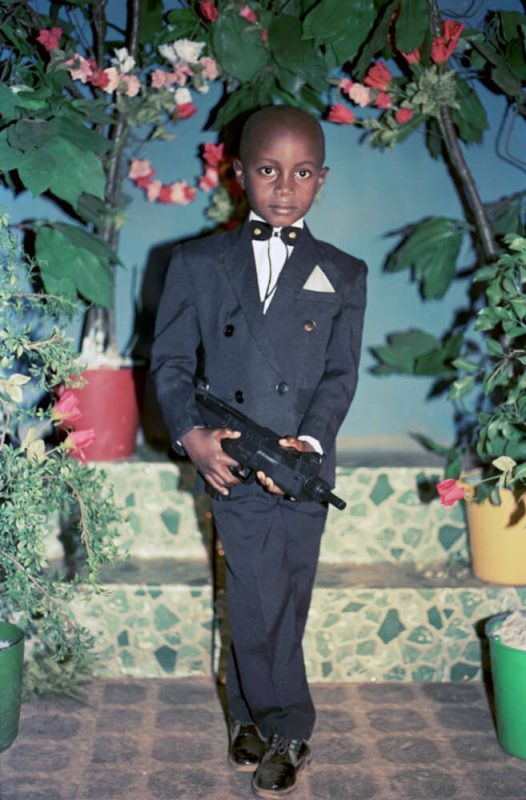

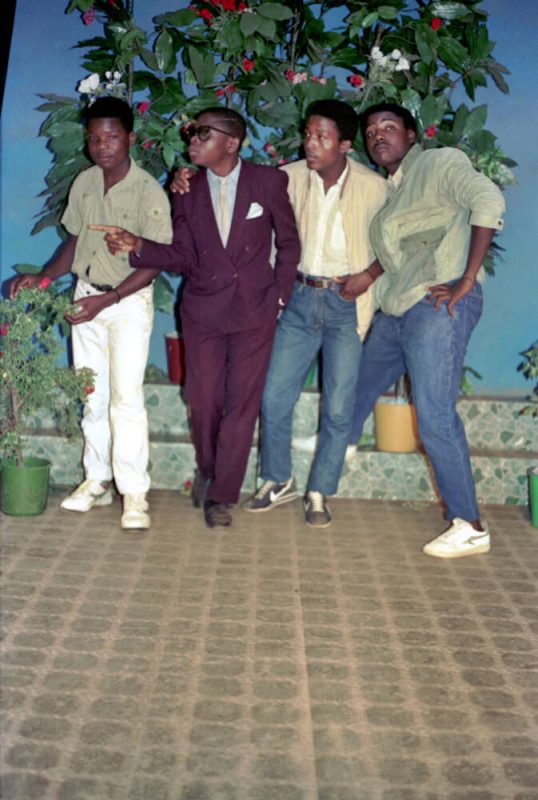

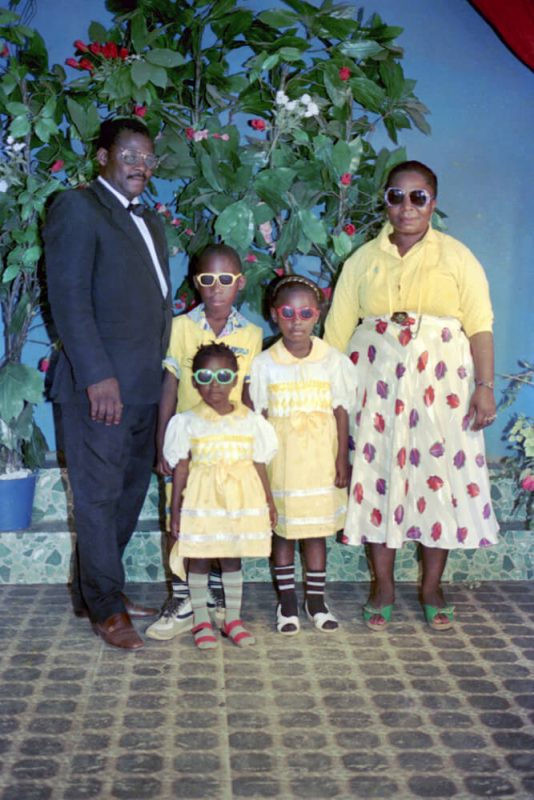

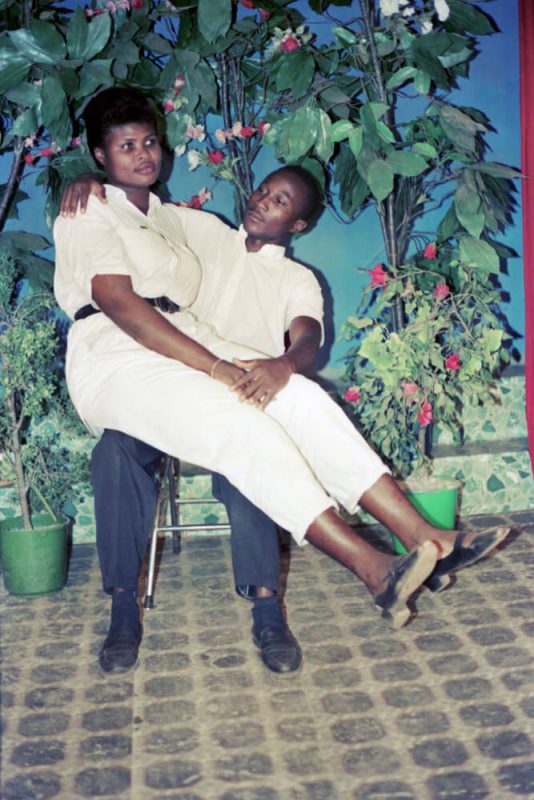

Irish artist Richard Mosse has developed a body of work looking at military testing, conflict and the technologies of photographic imaging, most notably in his lauded project The Enclave. The follow up is Incoming, a body of work comprising video in multiple formats, stills as a book, and large-scale prints about the mass-migration of refugees from Northern Africa and the Middle East, at the thresholds of Europe, in Turkey and Greece, and at the borders of Iraq and Syria. Mosse uses a military grade thermal camera to make his videos and photographs: his imagery spans from close up details of human interaction, fragments of group crossings of the Mediterranean, landscapes of war including missile launches, to the holding camps for refugees. Much of this footage is montaged into a large three-screen video projection (recently presented at the Barbican, London) and a parallel book; panoramic footage of the temporary camps are reconfigured into large scale prints – sometimes called Heat Maps, alongside a video installation that resembles a bank of CCTV cameras, panning left to right continuously in a dizzying sense of searching.

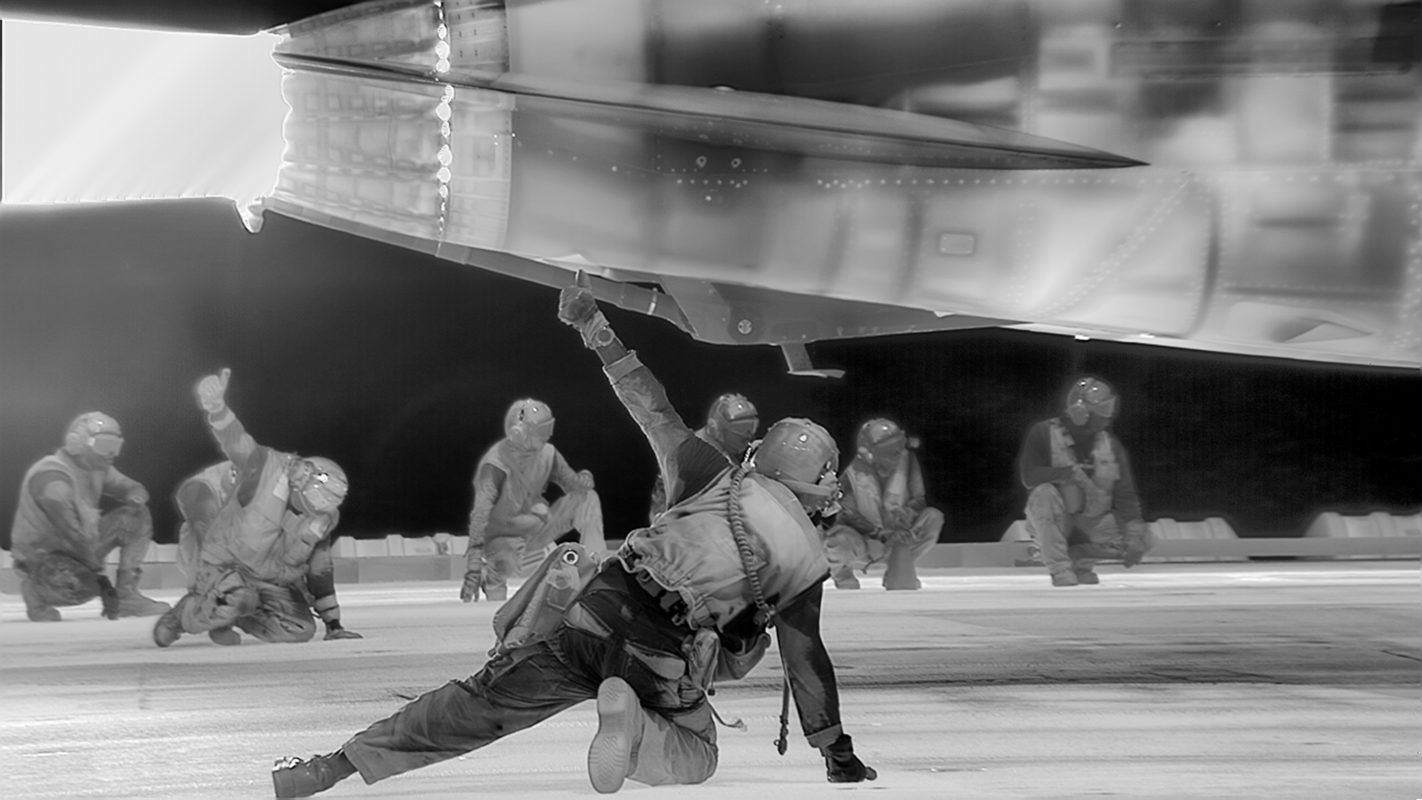

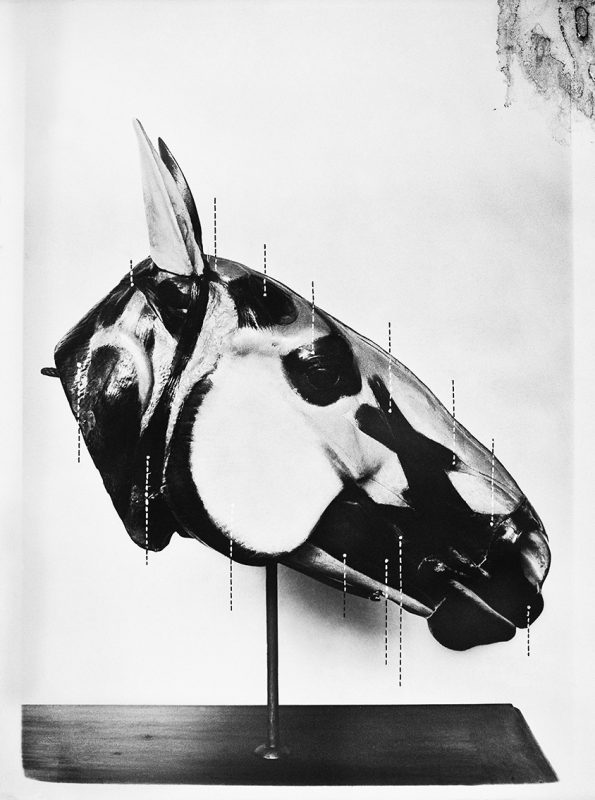

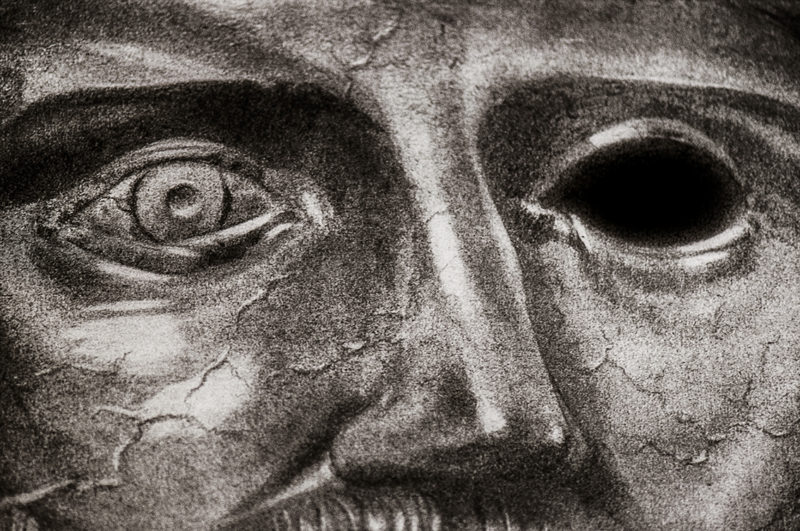

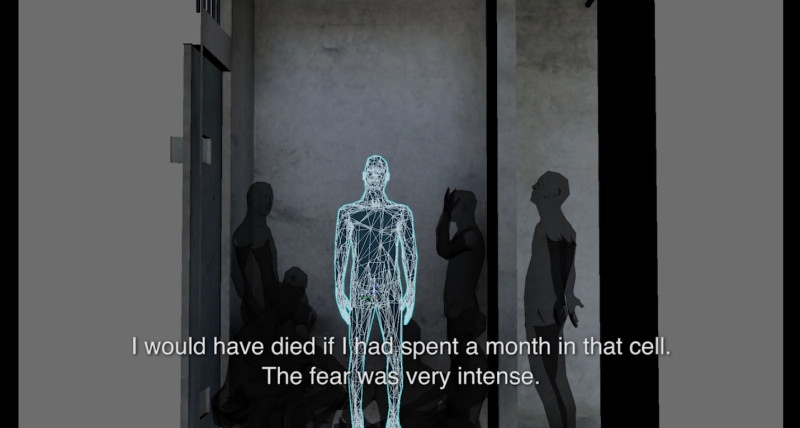

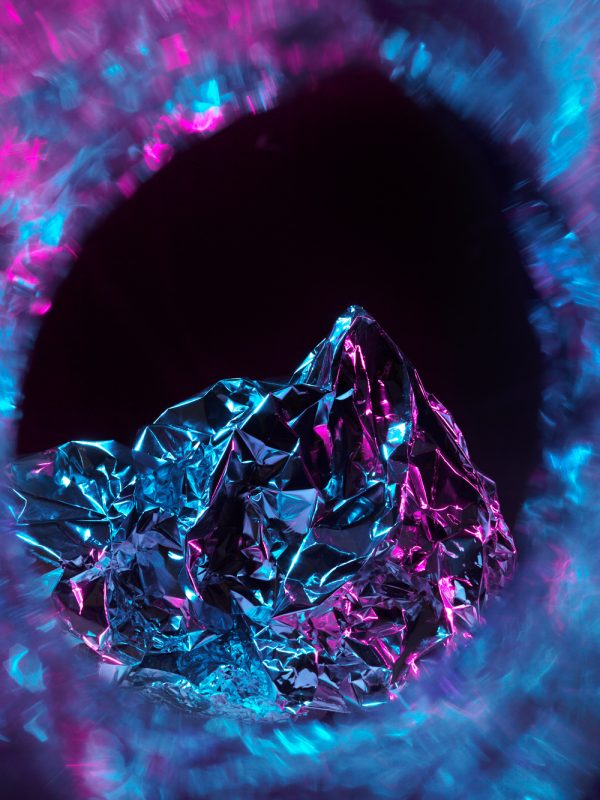

Although the effects of the thermal camera are not entirely unfamiliar to us (used by the police force, and utilised in both factual and fictional television and cinema, in photographic projects, and even as add-ons to a smartphone), it is important to establish what a military-grade thermal camera does and does not see. What distinguishes the camera from other equipment is its distance and precision of vision, being capable of detecting the human body at 30.3 kilometres. Although it’s primary purpose is to identify heat, it continues to register detail in a lower, flatter range of greys, unlike many thermal devices since the camera is black and white, and not in colour. Mosse’s prints retain a photographic language even if they are also at once unfamiliar. It is possible to differentiate spatial planes and surfaces, textures, and script clearly. The recognition of a figure is possible, although identification is slower and loaded with doubt. It is an image, but one that we are not entirely comfortable with. The thermal image prompts an alienation from the immediate transparency of the reportage image, even if the project retains a documentary scope and purpose. The refugee, already identified as other by the state, is transfigured again by the strangeness of the camera.

Suffice to say every camera dehumanises. In rendering the body into two dimensions, a photograph is lossy and reductive. But our familiarity with this property of the image has caused us to quickly forget and come to terms with the image and its compromises, accepting the trade off of the arrested and flat image for its portability. Yet criticism of Mosse’s project in this regard seems to conflate the technology with its use. The dehumanising of the body is of course continuous with the technology and operations of the state, which we understand as intermittently picking out and targeting the human subject with reasons that power justifies under the rhetorics of the war on terror, national security, and as Eyal Weizman has recognised, the chilling but pervasive moral logic of the ‘lesser evil’. If this is disturbing, it should be, though it is not Mosse’s doing, as he investigates its properties.

Mosse has stated clearly that his aim is to use state and military technology in order to know and use it, seeking new purposes for it. And in our slower observation of his imagery, the thermal camera reveals the state’s tendency to abstraction, to render the refugee as ultimately perishable, under a condition that the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben calls ‘bare life’. It is also, as Judith Butler writes, the very construction of a difference (nationality) that allows the ‘refugee’ or ‘foreigner’ to be perceived as a threat. We are barely conscious of this fact in our short encounters with the technology elsewhere, where voice-overs for police chases re-inforce the messages of law enforcement. Its estrangement when isolated is surprising, but Mosse sets out to do undo it, using the camera for cinematic effect, and to construct slow and pensive images. Mosse, like the state, often operates at a distance from his subjects – but does this automatically render the result of Mosse’s investigation complicit or continuous with a global order – and by extension, a flow of global capital, as has been suggested?

We must look at the project in detail rather than arriving at rash judgements. The camera continues the western project of producing ‘visibility’. We know that the camera extends human vision, seeing heat rather than light. And we know the purpose of this function already: it is to identify a body or object that attempts camouflage against the eye or standard lens. The lens therefore functions in a manner akin to much of photography’s post-industrial ‘program’ – to extend the range of the visible, to make a world saturated in visibilities. Significant also is its range: the camera provides an ability to see at extraordinary distance, and to see whilst remaining hidden – a logic of power identified by Foucault in his studies on surveillance and the prison. But this is also to state that the camera operates as any device under power: it provides an advantage that increases the visibility of its object, whilst removing of its own capacity to be seen. And Mosse, crucially, turns his camera towards what has been concealed. A similar attempt to wrestle back control of the visible emerges in Trevor Paglen’s Limit Telephotography project, customising cameras to see into US military sites – both occupy high and distant to positions to see sites that are concealed in some manner by the state. Mosse turns his camera to the structural logic of the refugee camp, showing it at a distance, alongside other images within the documentary devices of closely cropped individuals, though it must be noted that the distant images are far more revealing, and affective, because they defy a humanist photojournalistic norm.

In one image, it becomes clear that refugees are housed in and amongst shipping containers. Their equivalence with freight is telling, cold and statistical. But worse still, they remain unequal even in this comparison: it is substantially easier for the container to pass into Europe than it is for the fleeing refugee. How frequently is such a structural marginalisation made apparent?

Mosse is not always effective, however. His large-scale three screen video projection, whilst attempting to show the proximity of conflict and the dangers of the sea crossing, is narrative, dramatic, and as a result overly spectacular. Mosse gets too close to this structure of entertaining and theatricalising, and an accompanying musical score for the video here reveals a pandering rather than a challenge to the conditions of viewership. Mosse’s intention to make the structural logics of the thermal camera, and the experience of the refugee visible, is made apparent in a pensive image; it is obfuscated when it moves towards spectacle.

If the body is the subject of a dehumanised gaze under a military use of the camera, does the body remain a target under Mosse’s use? We have seen that the thermal camera alienates our view of the body in a way that typically functions under the logic of enhanced visibility, but can we say that its operator is programmatically or unconsciously positioning the refugee as other, extending their distance from us? Mosse’s images are affected by the conditions under which images are made, namely changes in climate: in the footage of his large three-screen projection and book we see blackened figures, with heat emerging around the top of the skull and mouth. It is cold and windy, and the temperature difference between the air and the body’s sweat picks out details on the skin. By contrast, In Mosse’s wide landscapes (of the Hellinikon Olympic Stadium in Greece, for example), the body is wholly illuminated, its warmth dramatically changing the body to white. If a military-grade thermal camera saw in colour as do other thermal devices, the body would be blue when cold and red when hot. Such a responsiveness to climate undoes the notion that the body is differentiated or cast as one race by the camera or its operator, as has been asserted elsewhere. But it also undoes a total flattening of difference, as has also been stated at the other extreme: the camera does not conceal the differing presentations of the body, how the body is dressed, marked or conditioned, at least for an observer prepared to look at the image in detail, beyond the estranging effect of the thermal sensor. But such observations distract from the main potency of the image and what it presents to us, leading to outraged claims at one pole, and hopeful but false universalities on the other – both are loud and reductive, when the experience of the refugee surely calls not to be caught in the crossfire, but to be paid attention to, to be seen and heard.

The presence of the live body affects us, as the camera isolates it. In our pause in front of the image, its strangeness causes us to see that warmth is the bodies strength and its very weakness, its similarity to us (however politically and economically removed). And here the flattening effect of the thermal camera is telling at last: it is hard to identify the difference between the military guard, aid worker, or volunteer, and the refugee. What unifies is more evident than what separates, at least for a moment. If we must perceive the refugee as a target under the night vision camera, so too is the aid worker and each member of military personnel. Perhaps this is because, as Agamben is so keen to point out, we are all determined by the conditions of the state. It is also because the body’s heat is its very force, and its very vulnerability: this is also shared by the refugee and the soldier, whose lives are equally fragile, however much we are conditioned to deny it.

As Judith Butler has stated, such realisation of the very fragility of life is the possibility to realise our interdependence upon each other. When we produce difference, and articulate otherness, it can be perceived that we in no way depend upon that life, in fact, are threatened by it. She states that: “Th[e] interpretative framework [of nationalism] functions by tacitly differentiating between those populations on whom my life and existence depend, and those populations which represent a direct threat to my life and existence.” Such a notion of non-dependence is structurally untrue of course: any analysis of the wealth of western nations could not fail to include the resources and labour extracted from the rest of the world. It is simply that trade conceals by abstraction, concealing where luxury comes from and how wealth is obtained.

In actuality, we are each dependent upon both the refugee and their legal mirror, the migrant, for our luxuries, but also for our lives: by producing and enforcing forms of otherness that dehumanise or delegitimise, we produce conflict. This conflict begins with an article and its rash claims, and ends with an enforced difference, a creation of margins, alongside a demarcation of the speakable and unspeakable, represented and unrepresented. What can we do to re-instate our proximities to the refugee? We must reveal our own dependency, and how our life is equally precarious. It is here that Butler is most persuasive: “the call to interdependency is also, then, a call to overcome this schism and to move toward the recognition of a generalised condition of precariousness. It cannot be that the other is destructible while I am not; nor vice versa. It can only be that life, conceived as precarious life, is a generalised condition, and that under certain political conditions it becomes radically exacerbated or radically disavowed. This is a schism in which the subject asserts its own righteous destructiveness at the same time as it seeks to immunise itself against the thought of its own precariousness.”

What is our responsibility then? Richard Mosse’s Incoming attempts to look at how the body is figured in the technological devices of power. His turning of this camera, towards the sites through which refugees pass, has seen how the body of the refugee is dehumanised, situated as a problem ‘incoming’ to the shores of Europe, which Europe has variously responded to, lashed out against and ignored. And we are implicated in it, are in fact, dependent upon it. It is a glimmer of human life that calls us. This might not lead us to see the refugee in a deep and personal light, but to see our relationship to all notions of otherness through the shared interdependence that underwrites human relations, and to see that the delineation of difference through exclusion exacerbates, and does not reduce our own security.

Mosse moves between spectacle and contemplation, and this project reveals the sharply different affects that such modes of address might engender. And here, precisely is our responsibility: to consider our mode of address, our mode of encounter, and to think it through thoroughly, without recourse to further exclusion, or diminishment. If a dialogue is in any way to propagate a more equal and tolerant consideration of “those who seem to test our sense of belonging or to defy available norms of likeness”, it will need to know no distance, near or far. It begins by setting aim at common ground.

*

In attempting to produce a detailed and critically nuanced account of a project that has divided its audiences, it seems necessary to address two notable criticisms of Incoming – that Mosse has little right to produce his project, and that he profits from it through the structure of the gallery system. That I do so is not to defend Mosse but to respond to criticism that pulls on the heart strings whilst arriving at problematic outcomes that run counter to their claims. I have chosen not to address such criticisms head-on in my essay on Incoming, seeing it as an attempt to see the work in a way that attempts to bring out a constructive possibility within Mosse’s use of military technology. I have, however, chosen to comment on these criticisms after, perhaps in advance of the plausible criticism that I have neglected their claims, but more significantly, to demonstrate that whilst I think their broad positions (on the ‘whiteness’ or non-representation of minority voices in art and its criticism, and on the problems of a political art’s relationship to money) are valid and worthy of debate, their application to Mosse seems driven by something else, which undoes the seriousness of those subjects at hand.

Mosse, like the American painter Dana Schutz, has been the object of strenuous criticism surrounding how we depict those we do not know. Both artists have been attacked for representing the lives and deaths of others. Schutz’s painting Open Casket, at the Whitney Biennial, has been criticised for its representation of the death of Emmett Till, whilst Richard Mosse has been criticised for his representations of the refugees arriving on the shores of Europe (though strangely, not for his previous project). It must be said that this criticism comes with both valid and invalid claims, which we must separate to reach a place of substance and criticism worthy of the name.

Let’s note the valid first. Criticism about racial representation has at its origin a concern to address the lack of diversity of critical voices and there remains a deficit in both art and photography. Such a lack is not simply the lack of a black voice (as was argued in the Schutz debate), but a truly global one, consisting of voices from genders, races, nationalities and social statuses alike. Such a position must rightly set only a global equality as its goal, but I suspect that attacking a white European artist for documenting a refugee crisis is not effective. Not only does it destroy one voice in favour of another (which it is to say it is antagonistic), but it also fails to remedy the problem by escalating tension about who can and cannot be represented.

It also follows that an experience of inequality or trauma in a community necessarily would be most tangible, empathetic and perhaps ‘authentic’ when communicated from within that experience. And no doubt there should be scope and audience for a photographic project that emerges from the experience of being a refugee – though it seems a position of luxury to assume that a refugee has the energy to focus on anything beyond survival. But I would also stress that Mosse never claims to speak on behalf of the refugee. He does, however, correctly point to our implication in the refugee crisis, something for which we need to see the consequences beyond our own mediated vision, and which calls for the project to be made visible to us. Such a criticism of Mosse can easily take the place of real reflection. Mosse’s logic to see how power sees is neither unreasonable nor without some gained knowledge. Yet it seems as if conventional demands of reportage are applied to Mosse by his critics, privileging some unspecified quality of ‘authenticity’, ‘immediacy’ and ‘fidelity’ which aims to humanise and affect the viewer into change. This is striking considering our nearly universal awareness that this method of ‘objective-and-yet subjective’ photography is barely possible, reductive and ineffective: Susan Sontag, Martha Rosler, and Allan Sekula critiqued the manipulations of straight photography some time ago. The efficacy of such ‘unmediated’ images are doubtful at best, and it is a relief to encounter an image of conflict that does not always attempt to reduce the complexity of human displacement to pulling on heart strings.

What is most problematic is that a destructive logic follows a desire to increase the representation of critical voices – a closing down, that argues we must speak only of our own experience, and not attempt to relate to another. This argument leads to the opposite of diversity, of course. As was declared directly and indirectly at both Mosse and Schutz in many of the critical articles that have surfaced, we must not intrude upon, and are ultimately excluded from, the experiences of others – one skin type disqualifies from any experience of another, and one experience of gender from that of another also. We should be cautious in the assertion that one’s validity automatically disqualifies another, not least because it replicates conditions of exclusion. This position emerges from wanting to clear the way for a new voice, but it counter-intuitively results in a stand-off and poses an impossible problem with consistently moveable markers – who is excluded, and who excludes?

It is undeniable that Richard Mosse’s work is increasingly expensive, and this must result in a flow of capital that benefits both the artist and his gallery. Both the photography and art worlds are increasingly industries in which the economic value of projects takes a symbolic value that affects and alters what is displayed in public spaces. And whilst there is no doubt that the exchange value of art needs discussion and actual change, it seems that the raising of this question in relation to Mosse serves not the purpose of addressing the economisation of art but rather the attempt to diminish his project in order to reinforce a criticism that a critic might otherwise sense is incomplete. An investigation into the economics of this artist’s career is yet to be done, but it is also let quietly rest in too many established careers to turn the attention on the work of a young artist. We might also bring a critique into being by celebrating projects which redistribute money or engage in alternative forms of exchange, which are no doubt quieter than the channels of debate of media usually permit. Such a criticism requires a search for its remedy, not a casual and unqualified accusation since rhetorical addition cuts off debate. What Mosse does with his success will of course be telling, and we might indeed hope that he supports critical and investigative research and affects political change. Yet it also seems a little too early, three projects in, to take aim at Mosse and discredit his work on the economic demand that a project comes to make. ♦

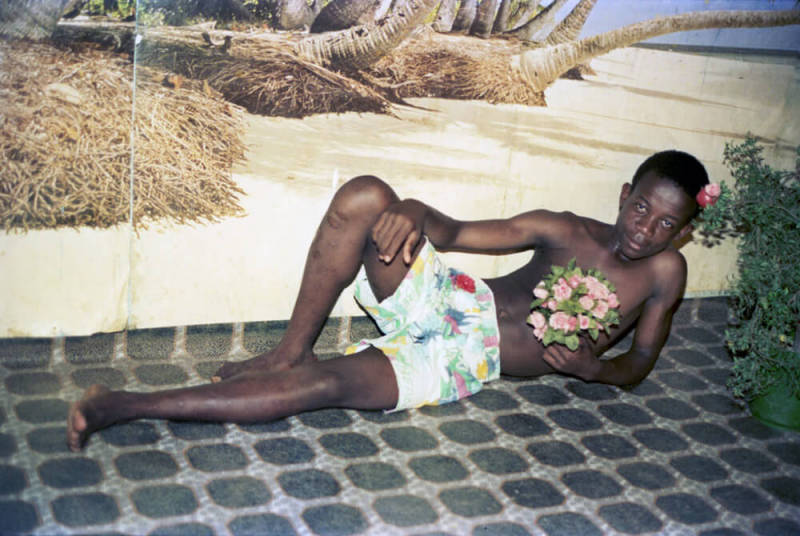

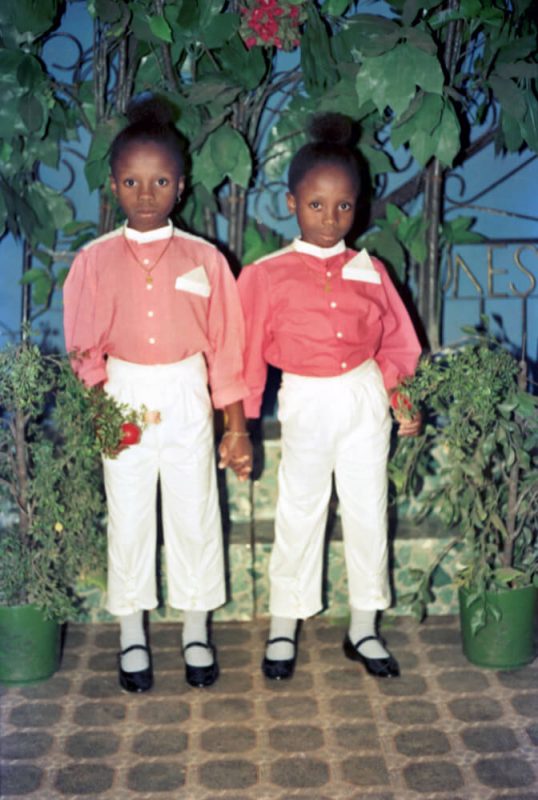

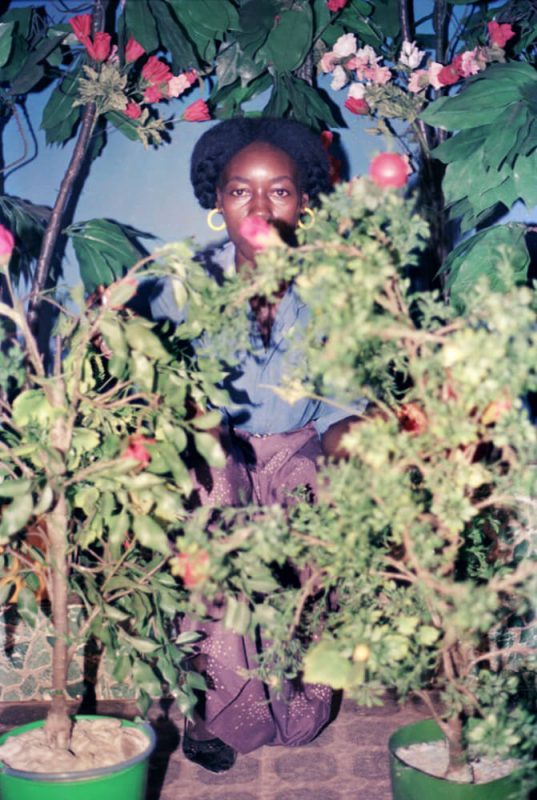

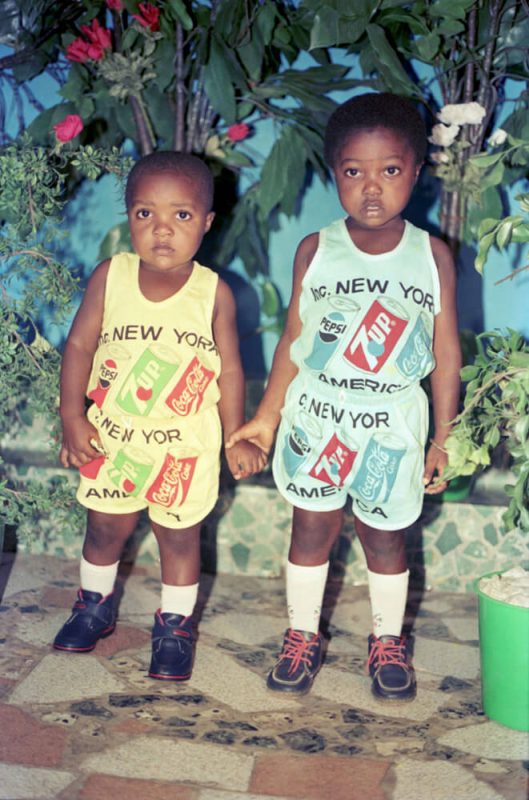

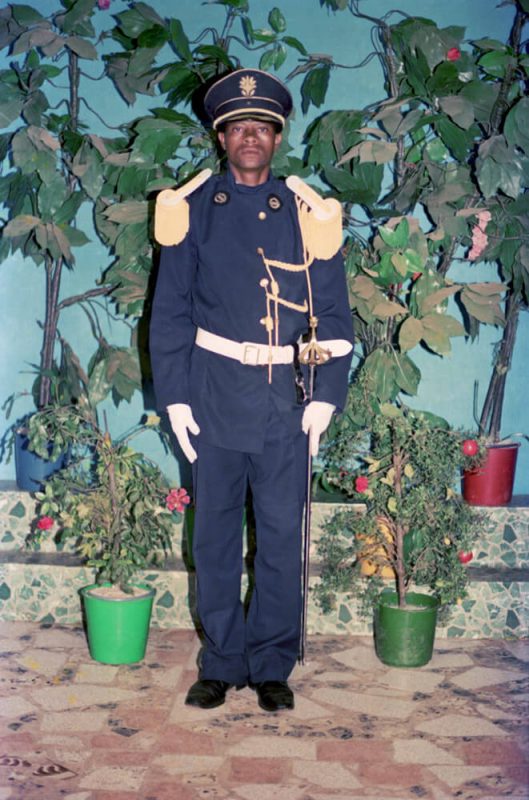

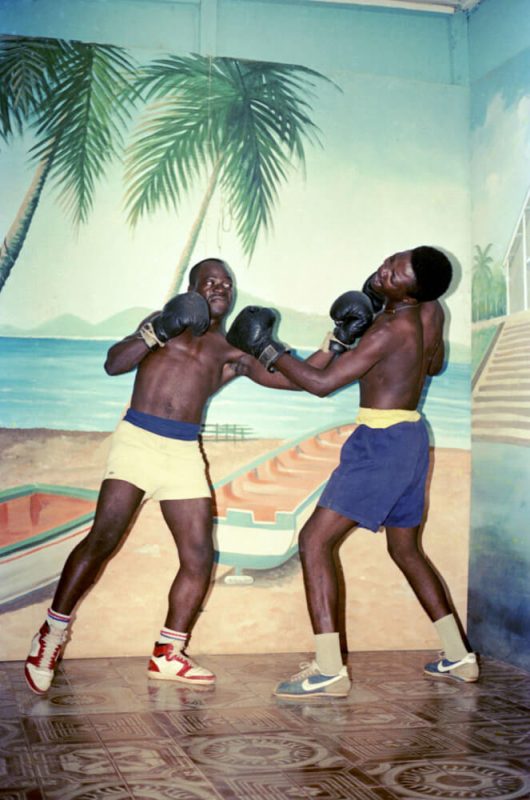

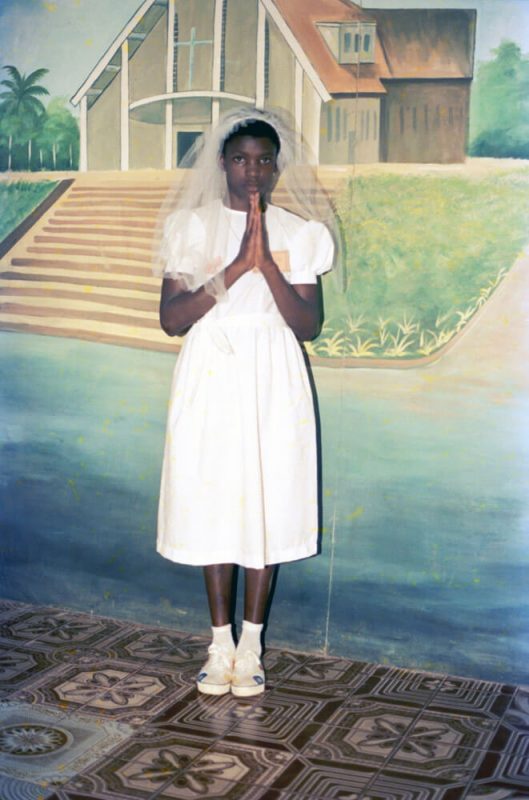

All images courtesy of the Barbican. © Richard Mosse. Installation views © Tristan Fewings/Getty Images.

—

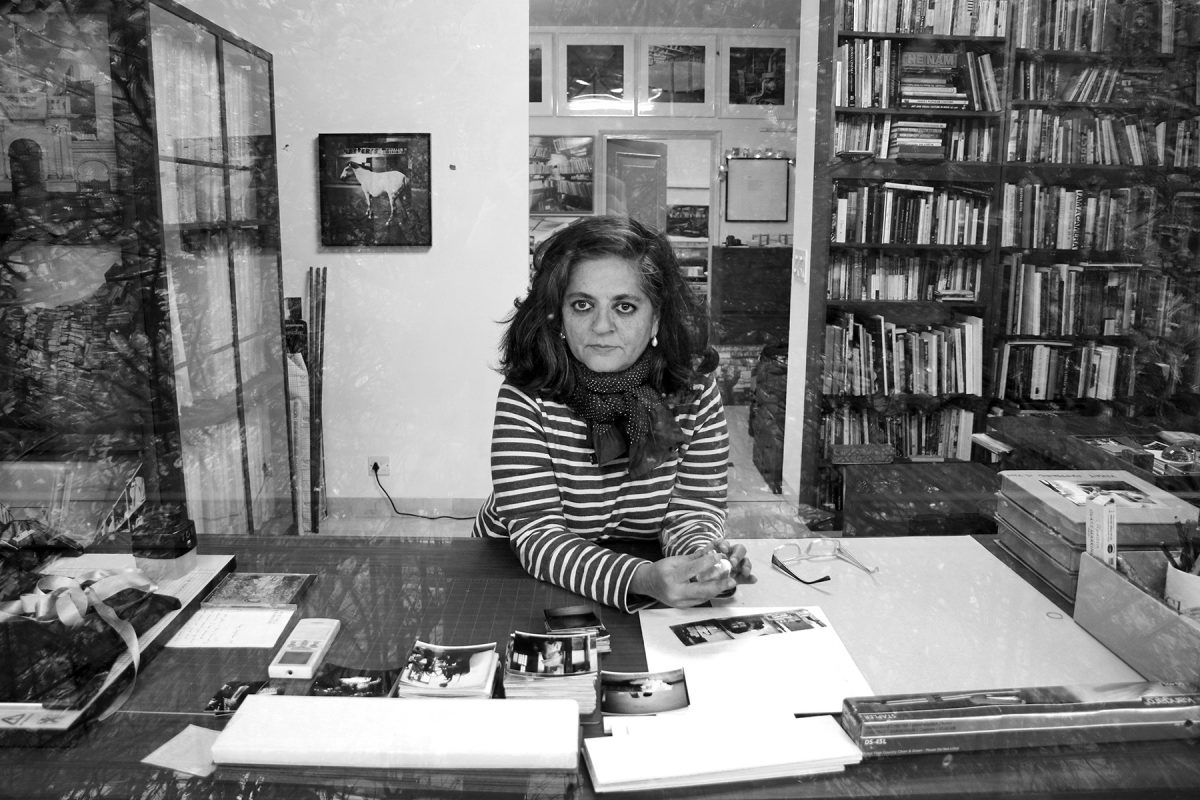

Duncan Wooldridge is an artist, writer and curator. He is also Course Director of the BA(Hons) Photography at Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London.