Top 10

Photobooks of 2019

Selected by Tim Clark

An annual tribute to some of the exceptional photobook releases from 2019 – selected by Editor in Chief, Tim Clark.

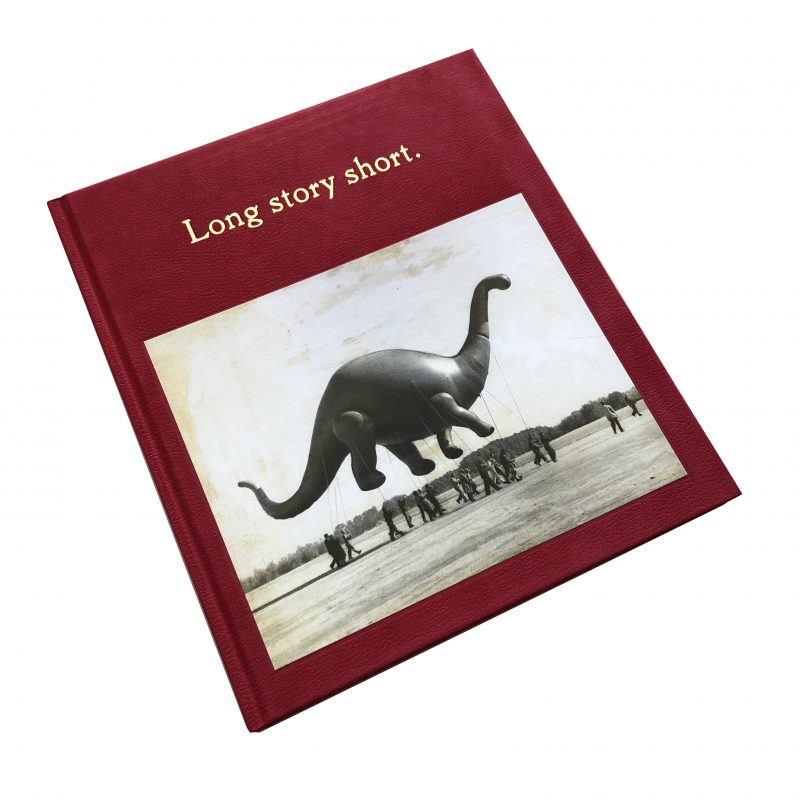

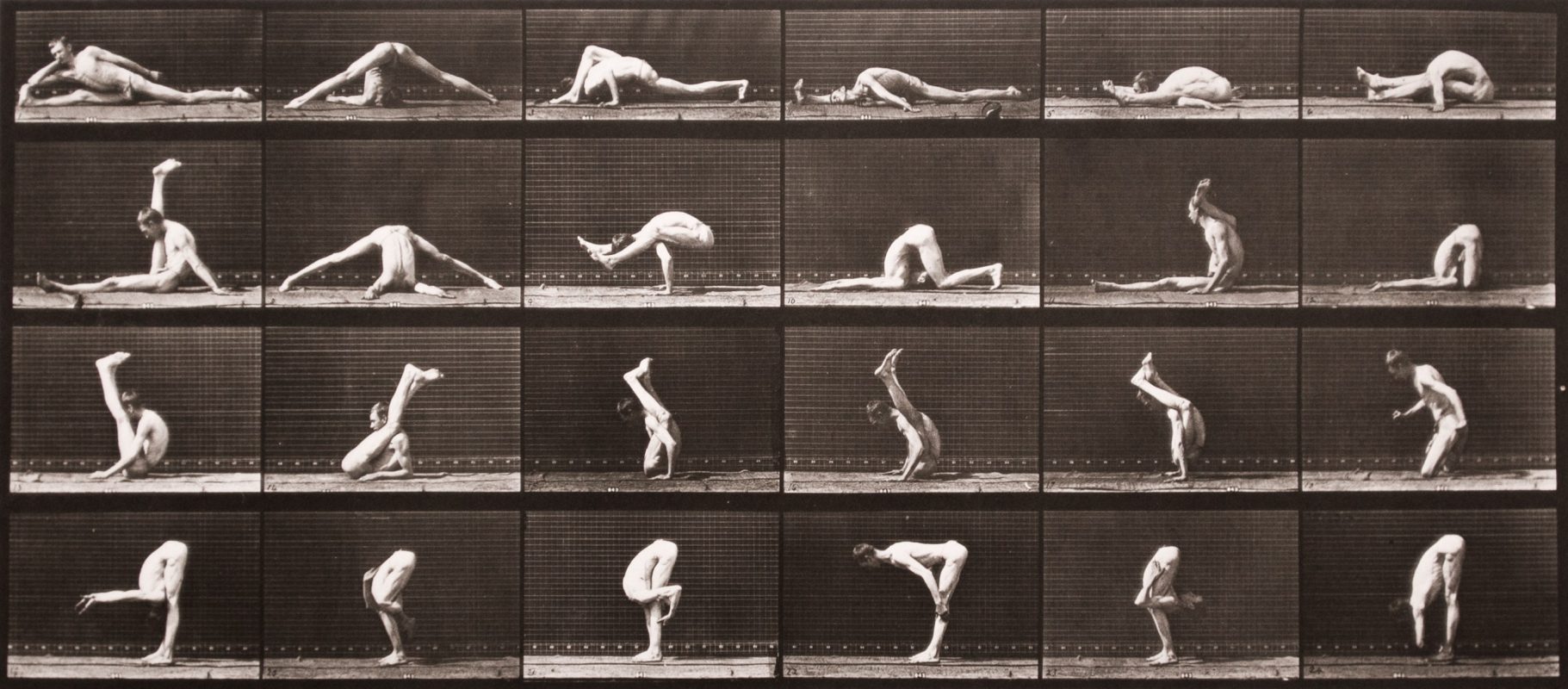

1. Long story short

Fraenkel Gallery

Long story short sees San Francisco-based Fraenkel Gallery return to publishing. Coinciding with the current exhibition marking the gallery’s 40th anniversary, this book is an endlessly rich slice of 180 years of photographic history. It aims to convey “that visceral sense of experiencing a work of art for the first time, in ways that defy words.” With a taste for the eclectic, it certainly delivers. Enigmatic photographs, such as the anonymous Untitled [Dinosaur Balloon], November 25, 1969 cover image, ricochet against immediately recognisable images from some of the medium’s stalwarts – Berenice Abbott, Man Ray, Katy Grannan or Eadweard Muybridge to name but a few – all continuing to entrance, all brought together in a celebration; not only of Fraenkel’s anniversary year, but to also retune our attention on the pleasures and rewards of sustained looking. With its sumptuous printing and lavish production values, Long story short is a joy to behold. A door to the heart of a gallery that has done so much to contribute to the culture, study and appreciation of photography as an art form in the United States and beyond.

2. Salvatore Vitale, How To Secure A Country

Lars Müller Publishers

As a case study to consider critical global issues, such as borders and immigration, Salvatore Vitale’s How To Secure A Country promulgates a timely and deeply-layered look at 21st century statehood. Edited with Lars Willumeit, this long-term visual research project – as opposed to an investigation of a ‘closed’ topic – deals with the machinations and protocol of security systems in Switzerland, a country widely regarded as one of the world’s safest. The work is organised into visual clusters to reflect the collaborations with individuals from different disciplines and via access granted by various institutions, both public and private, including those relating to borders and customs, cybersecurity, data centres, armed forces and even weather forecast and supercomputering. How To Secure A Country offers a privileged perspective and multi-vantaged point of view on the fraught relationship between individuals, power and state control, yet never through images that are self-explanatory, nor without pronouncing judgement. In Vitale’s work there is always space for the viewer.

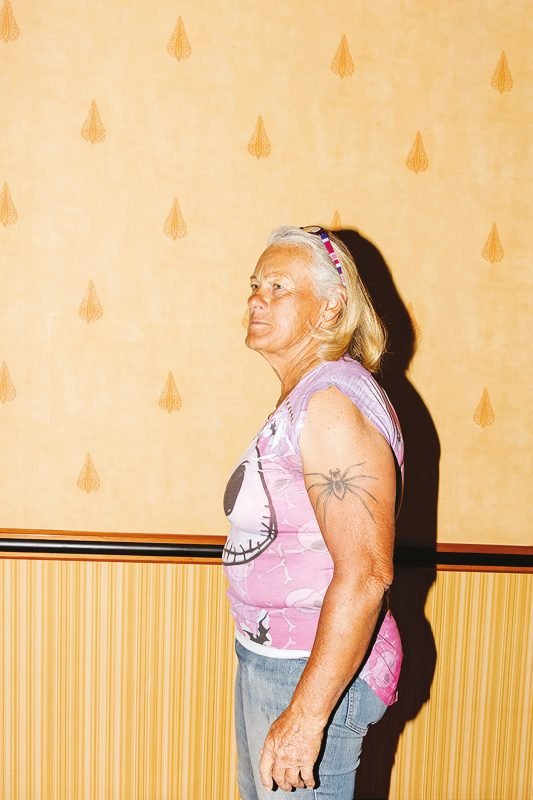

3. Lisa Barnard, The Canary and The Hammer

MACK

Another book of first-rate intelligence is Lisa Barnard’s Canary & The Hammer, spanning four years of photographic work shot across four continents. The artist’s third monograph takes gold as a subject – its complex history, relationship to wealth accumulation and symbolic representation – to demonstrate its myriad of uses and ubiquity in modern life. Deftly combining image, text and archival material within a structure of seven chapters, Barnard’s project embraces a fragmented narrative as a metaphor for our dissonant and uncertain times. Overlapping disparate yet related stories, ranging from the 1849 Gold Rush or activities by Peruvian mining organisations to jewellery manufacturing and high-tech industry, hers is a larger vision comprised of systems, contradictions and affects, ultimately cognisant of capitalism’s proclivity to both exploit and self-destruct. Throughout her career, Barnard has rigorously tested and questioned parameters within contemporary documentary practice, all the while reflecting on photography’s ability to render visible such vast and seemingly unimaginable themes.

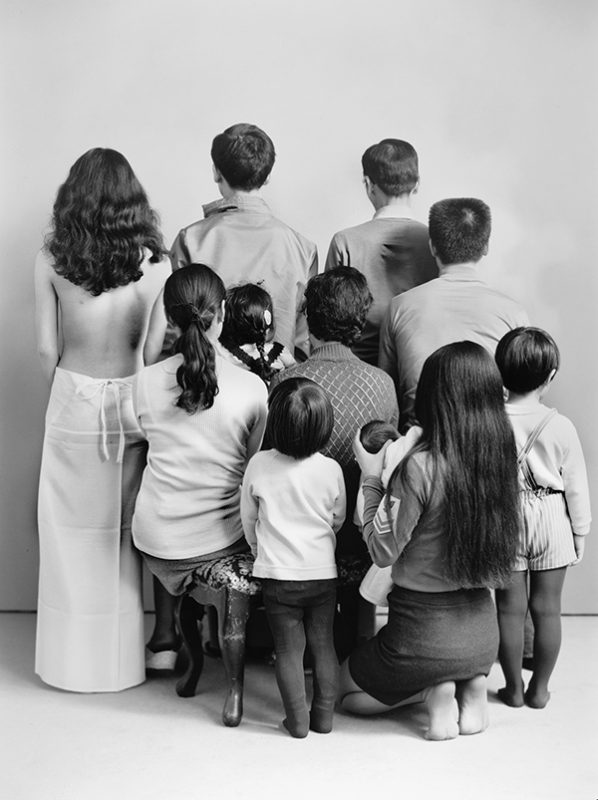

4. Masahisa Fukase, Family

MACK

It’s a swell time for reprints of photobook masterpieces. And MACK has been leading the way in recent years. Amongst its latest have been Larry Sultan’s Pictures From Home and Alec Soth’s Niagara, and now comes Family by giant of Japanese photography, Masahisa Fukase. First released in 1991, and the artist’s final book, the project centres on a series of group portraits showing Fukase and his relatives in the family’s professional studio that were shot over nearly two decades. Family utilises the ritual of the family portrait but subverts it by featuring various nude or partially dressed women, many of whom are young performers or student actors bearing no relation to the family. Melancholy is piled on melancholy in these photographic gestures of commemoration. Touching on issues of memory, empathy and dispersal, it reflects what Geoffrey Batchen has referred to as “the desire to remember, and to be remembered”. And as Tomo Kosuga notes chillingly in his parting words to one of the book’s essays, Archiving Death: The Family Portrait as a Site of Mourning: “As we meet their staring eyes, we may feel that the process of the mourning vigil, conducted around the Fukase family, is taking place within ourselves.” File under: ‘essential titles’.

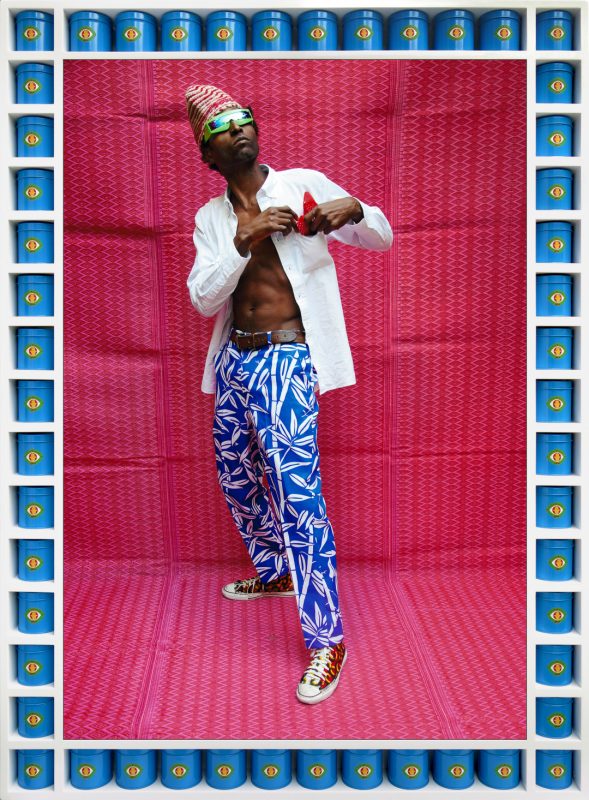

5. Hassan Hajjaj, Hassan Hajjaj

RVB

As the eponymous title suggests, this is a book about the vibrant Anglo-Moroccan artist Hassan Hajjaj – his creative universe, unique visual language and cultural remixing – that provides a noteworthy contribution to this year’s offerings. Remarkably this is Hajjaj’s first major monograph, produced to accompany the recent retrospective at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris. It draws upon his signature colour work that so effortlessly and promiscuously straddles modes of documentary and fashion photography. It also reunites this with hitherto unseen black and white work. His is an approach to studio and street portraiture that harks back to the traditions of Malick Sidibé, but which is given a contemporary twist through the bricolage of high and low cultural references in order to shine a light on the louche of global consumerism. The book’s design perfectly augments the content of the imagery by drawing out the repeated motifs and all-over compositions in an explosion of patterns and visual textures. Pluralism and new signs of recognition are the order of the day.

6. Anastasia Samoylova, FloodZone

Steidl

Necessary images from the frontiers of climate emergency in the southern United States make up this brooding exploration of the people, spaces and surfaces existing in preparation of its onslaught. Rising sea levels and hurricanes threaten but it’s the absence of any drama or action that defines Anastasia Samoylova’s FloodZone. Instead, as individuals wait and look on, conjured is an atmosphere akin to a mood piece laden with suspense and foreboding. Through a skilful blend of luscious imagery, encompassing lyrical documentary photographs and black and white studies – by turns staged and spontaneous – along with epic aerial views, and touching upon issues of paradise, tourism, decay and renewal, FloodZone constitutes an inventive addition to the slew of recent approximate visions of the Anthropocene. As David Campany notes in the monograph’s essay, “Paradise is as photogenic as catastrophe.” And while “the seductive contradictions of a place drowning in its own mythical image” is indeed embodied, Samoylova’s is a fantastic double vision, proffering depictions that oscillate somewhere between the already seen and never seen.

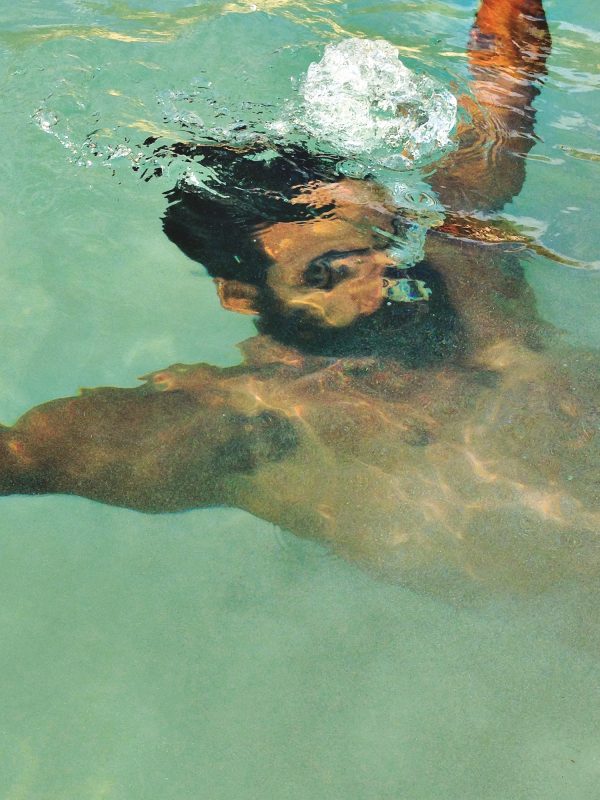

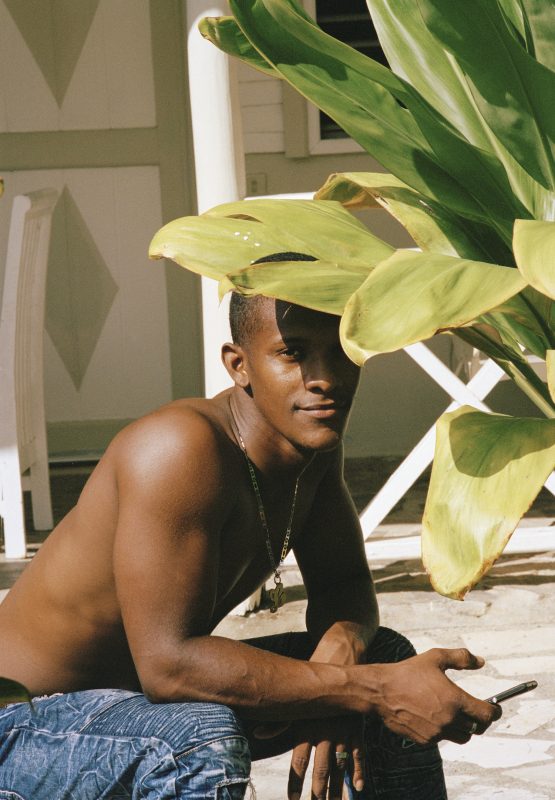

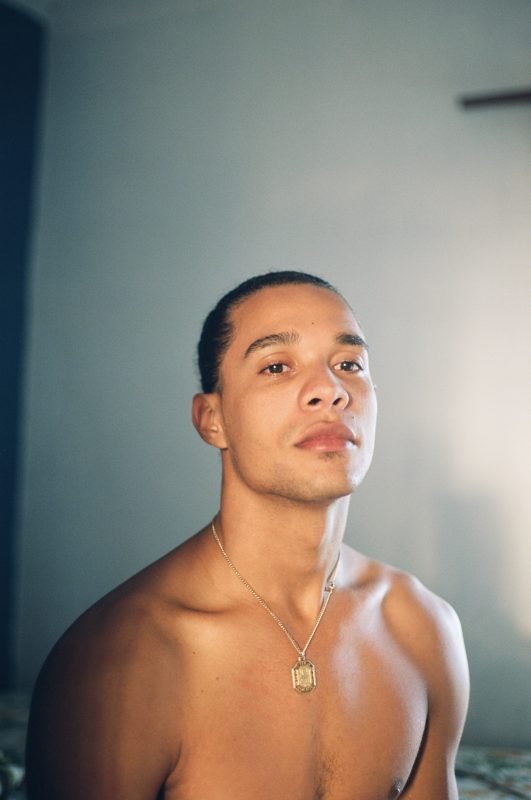

Readers of 1000 Words will recall the recent magazine feature on this highly-original monograph. Within it, French-Dominican artist Karla Hiraldo Voleau has made it her business to take us on a journey through her personal history in Hola Mi Amol, one that burrows into her dual heritage, its influences and prejudices. As a child Voleau was often warned to treat Dominican men with suspicion, ergo the slightly leery title of this book project, and here she returns to the island of her youth to actively seek out those very individuals she was warned about. A cast of nude or partially-dressed men populate the photographs – seen at the beach, in homes and motels or riding on the back of motorbikes via selfies with the artist – in images that both resist the admonishments of her family and, by natural extension, play us as viewers on a meta-level. Combined with text extracts, Voleau’s intersections call into question ideas of authenticity and ambiguity in the narration of the artist’s various encounters. Hola Mi Amol speaks through the most personal and private experiences relating to eroticism, prowess and racial identities. Ultimately the male gaze has in effect been turned on itself to powerful, and at times beguiling, effect.

8. Sohrab Hura, The Coast

Ugly Dog

Blood splatters, smoke bellows, tattoos sore, rats cower, tears fall – the visual experience of leafing through Magnum photographer Sohrab Hura’s fourth monograph The Coast is akin to a feverish dream. Chosen by the jury of Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation Book Awards as Photobook of the Year, there is something clearly so captivating about The Coast. And what’s interesting eventually winds up beautiful too. Opening with an absurd short story of a woman named Madhu, who has quite literally lost her head, the tone is set for an intense and unrelenting narrative that Sohrab relays in twelve varying iterations. It features photographs taken up and down the Indian coastline that work in service of what the artist refers to as “a metaphor for a ruptured piece of skin barely holding together a volatile state of being ready to explode.” Images are printed full bleed with only a narrow white gap creating a continuous visual flow – or assault – while their shifting contexts furnish our gaze onto a disorientating post-truth world, particularly in a country where disinformation and acts of violence are on the rise. Reality teeters between fact and construction in this fable for the times.

9. Amak Mahmoodian, Zanjir

RRB Books/IC Visual Lab

“This book is a conversation imagined between the artist Amak Mahmoodian (1980-present) and the Persian princess and memorist Taj Saltaneh (1883-1936).” So reads the preface to Zanjir, a riveting book hot off the press by Bristol-based, Iranian-born Amak Mahmoodian. What unfolds through sequences of quiet photographs – both authored and appropriated from the Golestan archives in Tehran – is a moving meditation on the actuality of having one’s family based there but no here and the hybrid experience of living between cultures, lands and languages, all bound up in sensations of love, loss and longing. From the subtle gaps between recording and not forgetting emerges this deeply poetic look at the vestiges of the past as they move into the present only then to become the past again. Time, memory, dreams and their inevitable decay approach something so powerful as it relates to the homeland. Mahmoodian, by her own admission, has created “a life of memories” swaying between presence and absence. With a stellar team of editors including Aaron Schuman and Alejandro Acin, Zanjir is a personal and rich foray into the imagination of an understated and poetic artist.

10. George Georgiou, Americans Parade

Self-published

This is the kind of photography that renews a feeling of wonder every time we gaze upon its imagery. Here, we are witnessing the theatre of life as seen through the parade of Americans during 2016, the year Donald Trump came into office and when the country had revealed its profound fractures. George Georgiou’s black and white photographs show one community after the next in a project spanning 24 cities across 14 states. Crowds of various sizes are captured via a simple but effective approach of photographing wide and from a distance to form tableaux-style images, their constancy bestowing a feeling of detachment but also one of acute observation. Revelling in the abundance and complexities of individuals who make up group identities, it is almost as if Georgiou is invisible – such is the candour. In these instances, people never stare down the camera, but instead focus on something beyond the frame. And they resonate with us, so pressingly that we look for ourselves in them. As we scrutinise the minutiae in such detail, images within images emerge, resolving into a kaleidoscope of mini portraits that are full of contemporary trappings. It thus offers up a valid document; in the same way the various locales reflect the socio-economic disparities of the United States to speak volumes of the environments in which the photographs were taken. Something must be said of the book’s quad-tone printing and its importance in revealing the sumptuous detail of the scenes, which, combined with lay-flat binding, allows viewers to really enter the imagery: exquisite. ♦

—

Tim Clark is a curator, writer and since 2008 he has been Editor in Chief and Director at 1000 Words.

Captions:

1-Eadweard Muybridge, ,

2-Salvatore Vitale, A customised assault rifle transformed for sport purposes, from the series How To Secure a Country, 2014-18.

3-Lisa Barnard, Gold-miner Kimberly, at the Las Vegas Gold & Treasure Show, 2017, from the series The Canary and The Hammer.

4-Masahisa Fukase, from the series Family, 1971–89. Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris.

5-Hassan Hajjaj, Keziah Jones, 2011. Courtesy Vigo Gallery, London, and Taymour Grahne Gallery, New York.

6-Anastasia Samoylova, Park Avenue, 2018, from the series FloodZone. Courtesy Galerie Caroline O’Breen, Amsterdam.

7-Karla Hiraldo Voleau, from the series Hola Mi Amol.

8-Sohrab Hura, India, 2014, from the series The Coast. Courtesy Magnum Photos.

9-Amak Mahmoodian, from the series Where Time Stood Still.

10-George Georgiou, 4 July Parade, Ripley, West Virginia, 04/07/2016, from the series Americans Parade.