Janire Nájera

Atomic Ed

Book review by Alice Zoo

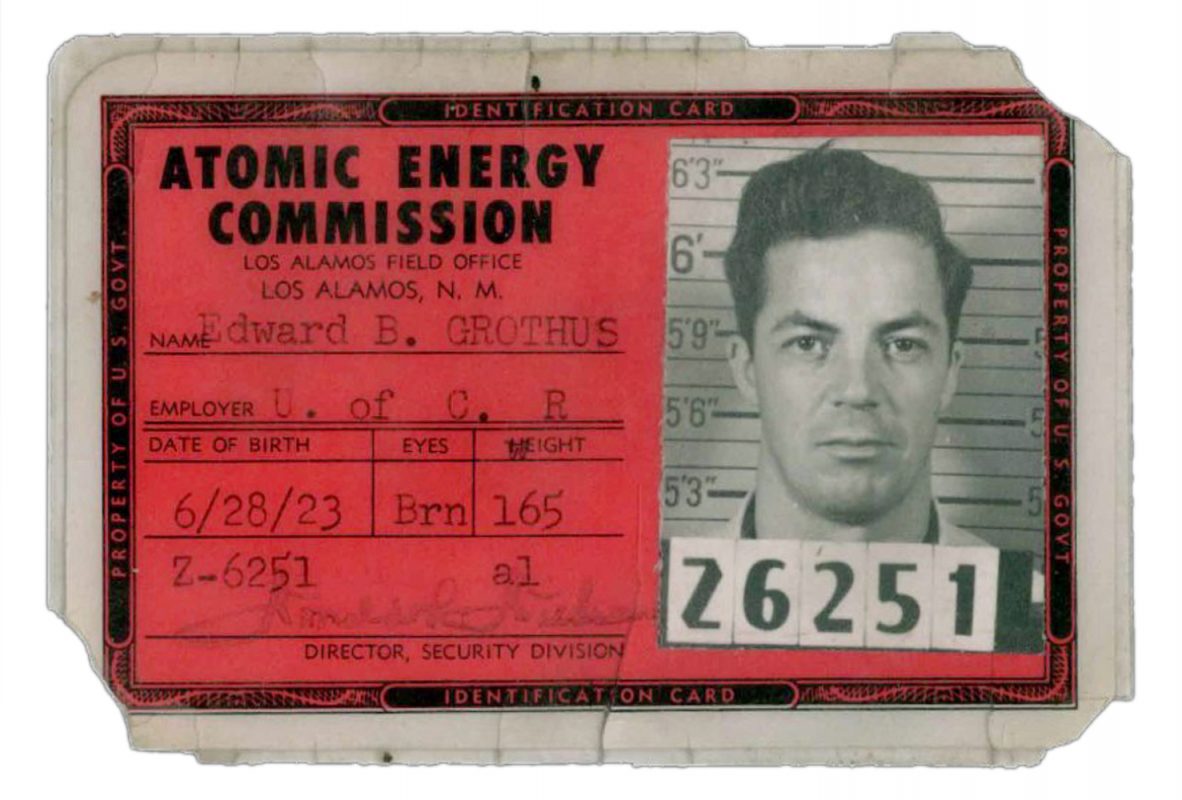

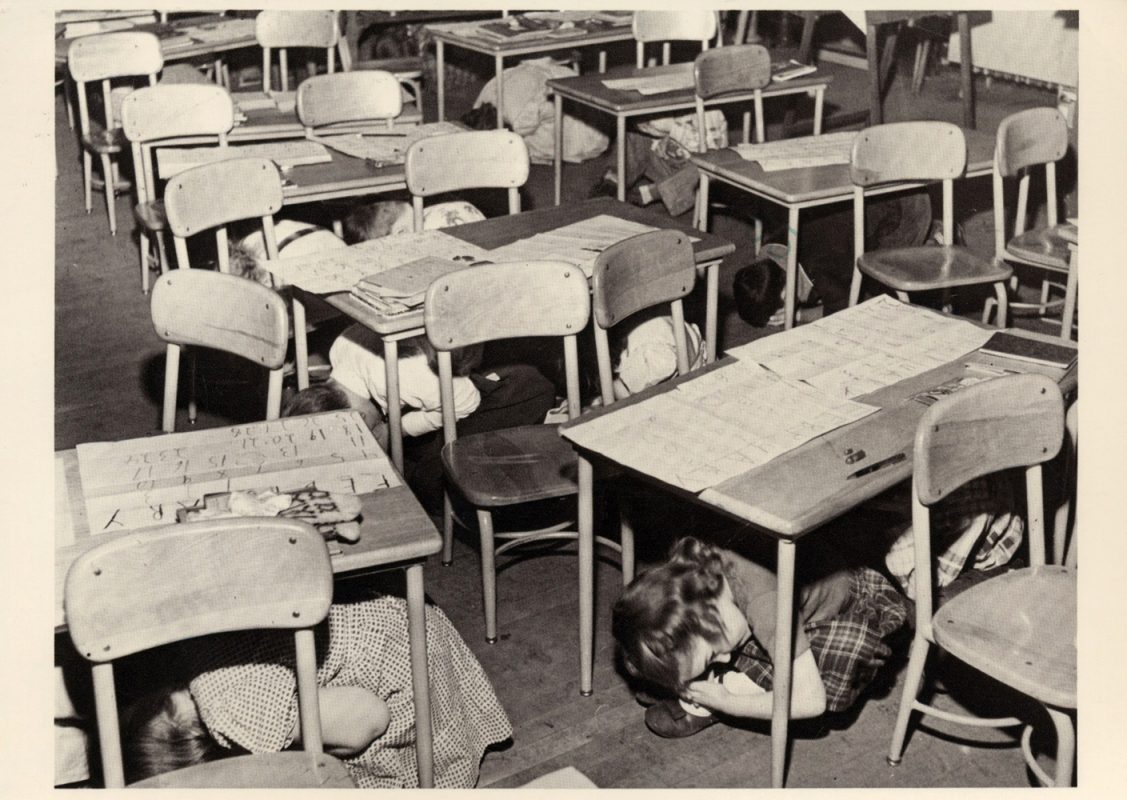

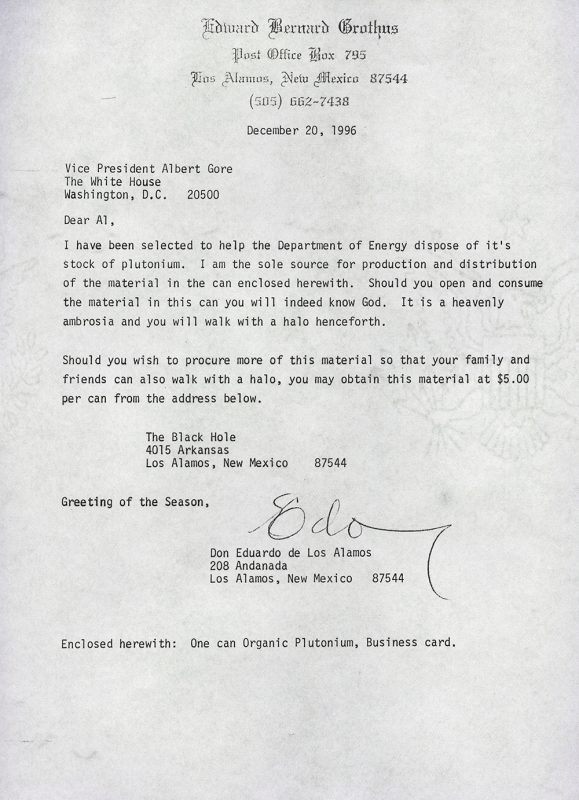

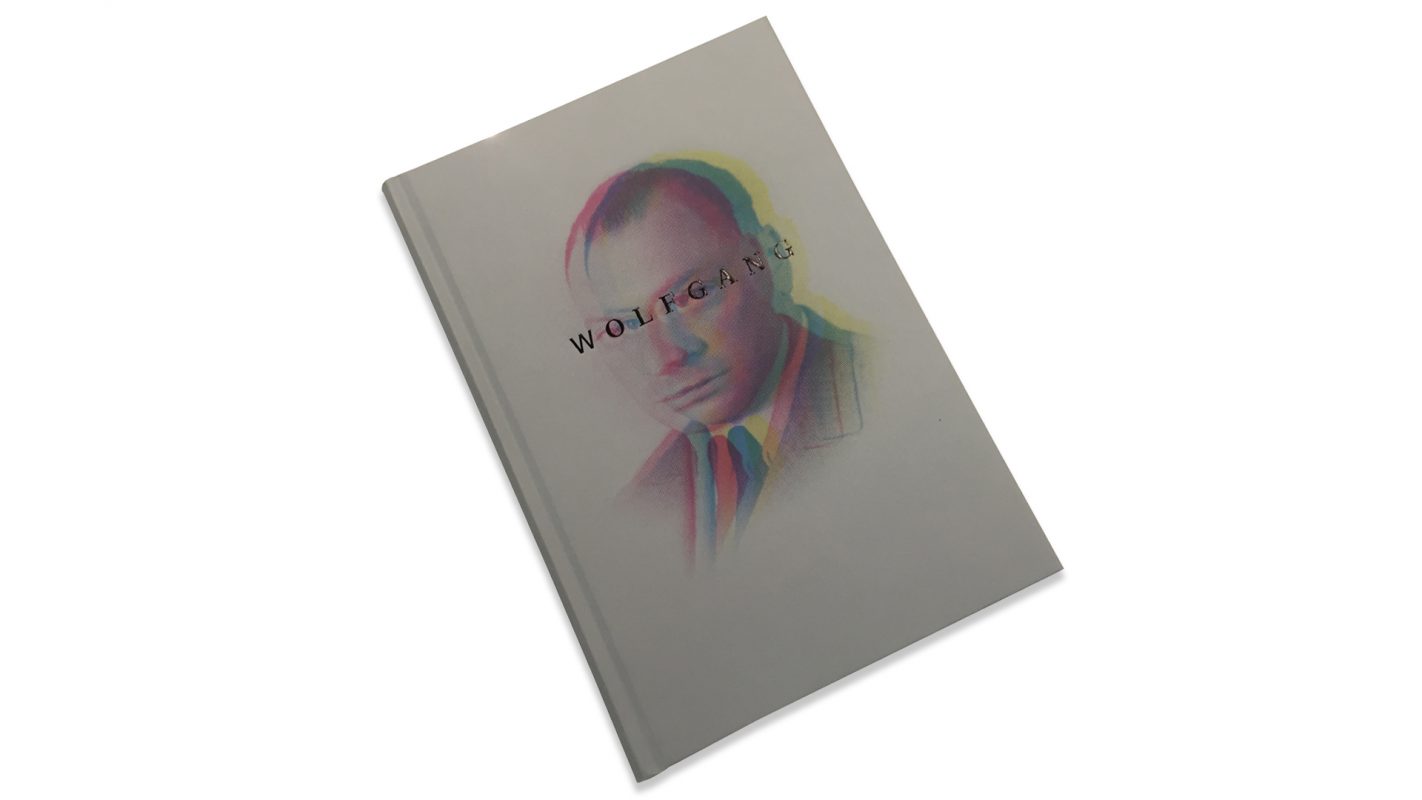

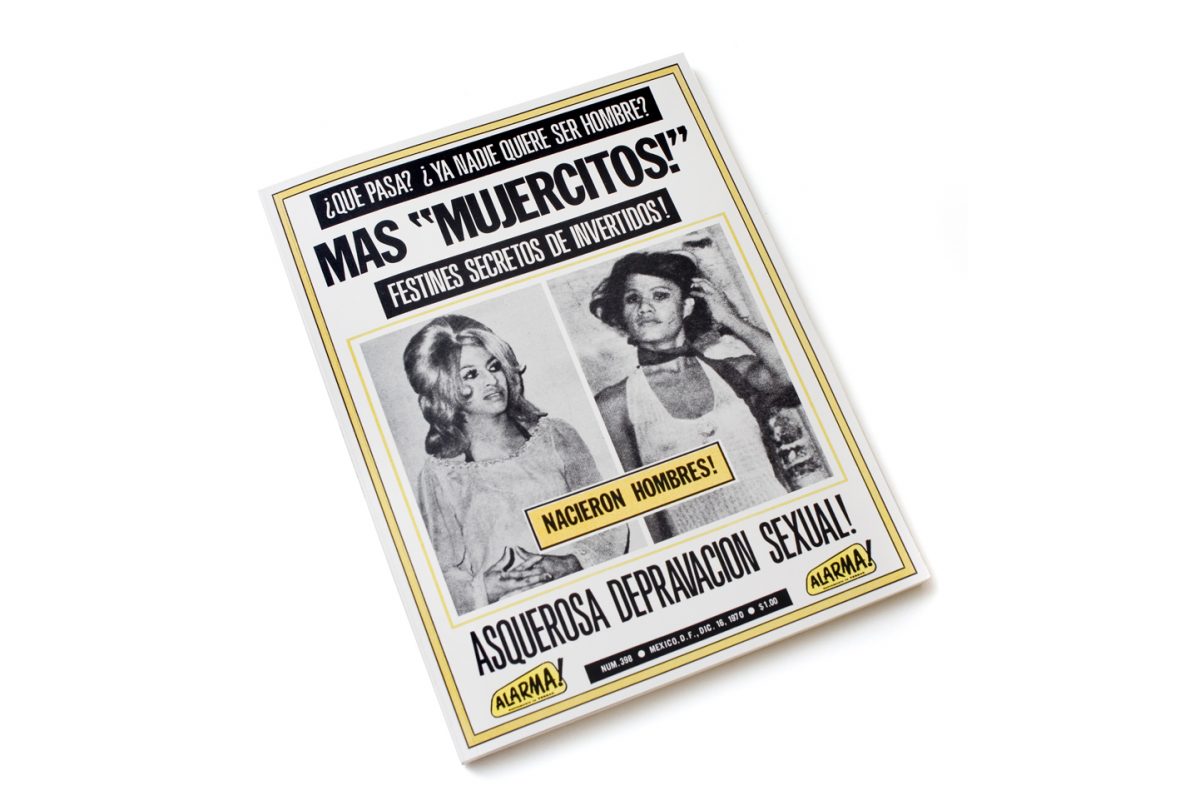

An envelope marked ‘SECRET’ falls out of Atomic Ed when the book is opened. Inside is an informational leaflet entitled ‘You and the ATOMIC BOMB: what to do in case of an atomic attack’. We are cautioned that “An entire city could be crippled temporarily by one bomb,” and “If you are above ground anywhere within three quarters of a mile from the air burst, you will have less than a 50-50 chance of survival.” We are told to roll towards a wall if no shelter is available, and to cover our heads from the heat and flash and radiation of an air burst. Despite the above, the leaflet positions itself as rational, empowering, even soothing: “If you are one of those who has said to yourself, “There is no defence against the atomic bomb,” the facts, as you will see, are otherwise.” Its inclusion within the project primes us, a contemporary audience living without such immediate fears, for the context that informs the work: the threat of annihilation, the gargantuan power wielded by governments and scientists in pockets of the world like Los Alamos, New Mexico. Janire Nájera immerses us within this context, and introduces us to one of the bomb’s fiercest opponents – whose moniker lends the book its title – Edward Bernard Grothus.

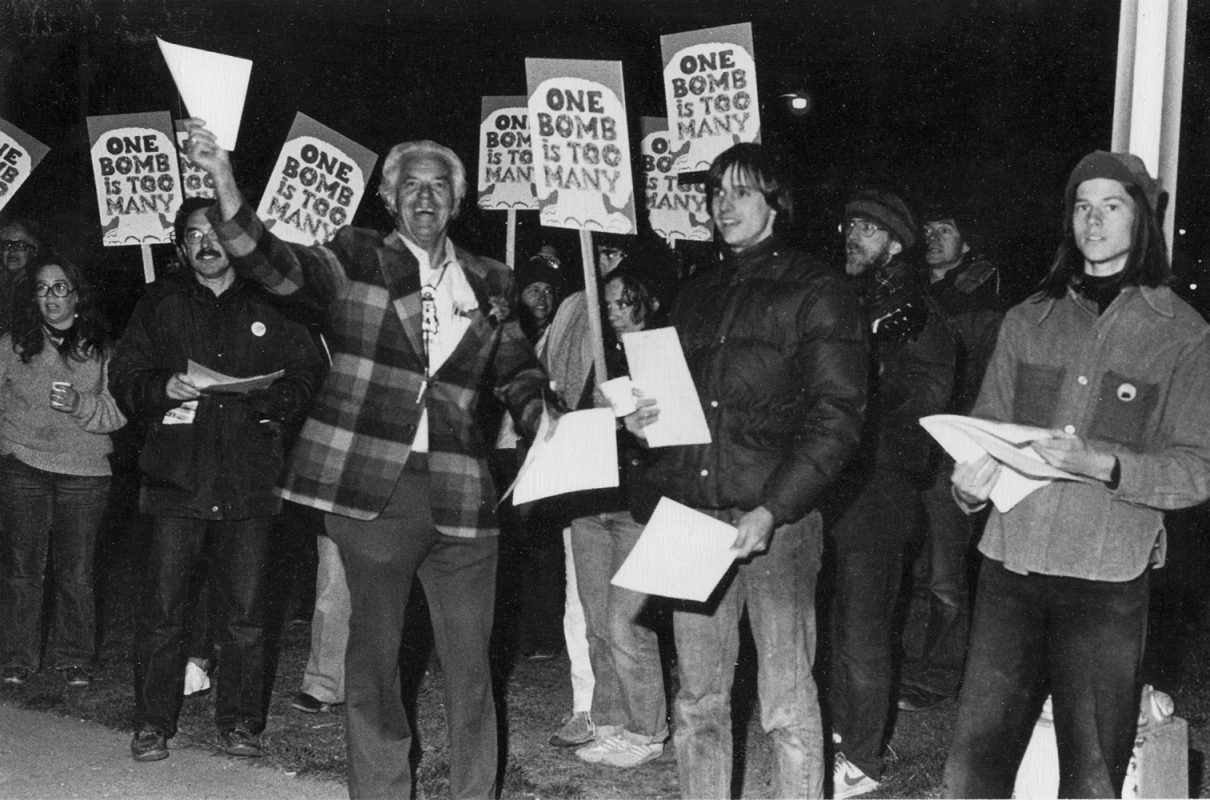

Nájera’s book project, published with Editorial RM, is the result of six years spent travelling to New Mexico and sorting through Ed’s archive, curated and presented here in the form of a remarkable narrative which makes up the first half of Atomic Ed. We meet Ed as a young man, rejected from the military on medical grounds, travelling through South America. The first images in the book interweave formal portraits of Ed’s parents with an image of him as an infant, the origin story of an understated hero. In one early image, he gazes out across a Rio de Janeiro skyline, hair slicked back. Soon after that photograph was taken, at the age of 26, he accepted a position as Machinist at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, helping to develop and refine the atomic bomb itself. At this point, the narrative skips and fractures: we see Ed much later in life, beaming, bobbing amongst a rally of people bearing signs announcing one of his favourite slogans: “One bomb is too many.” It is here that we meet him as he came to be known. Atomic Ed was a campaigner, a lifelong agitator against the atomic bomb, its consequences, and the brutal decisions made by those in power.

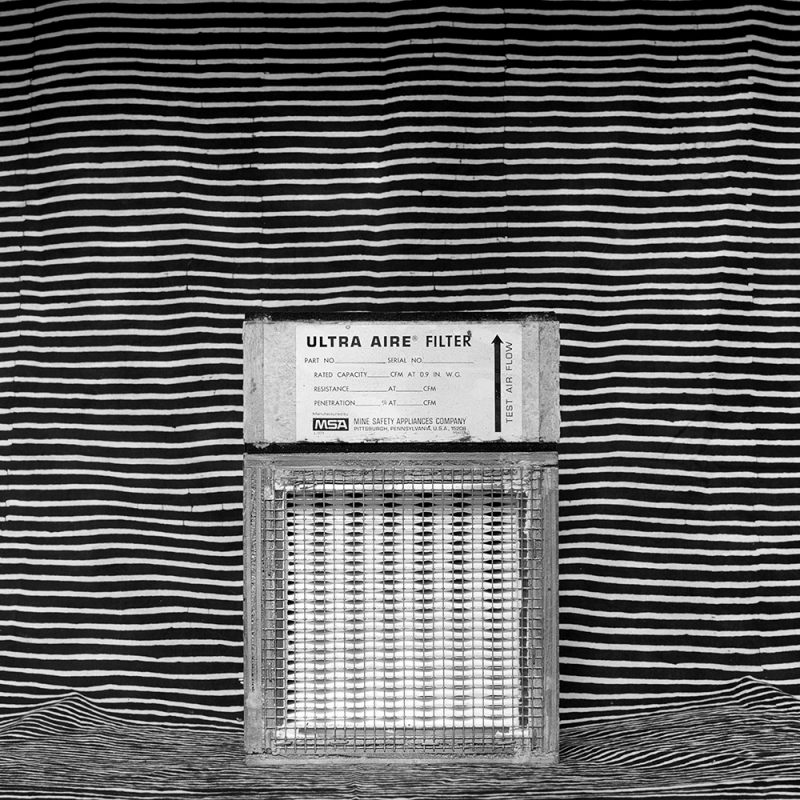

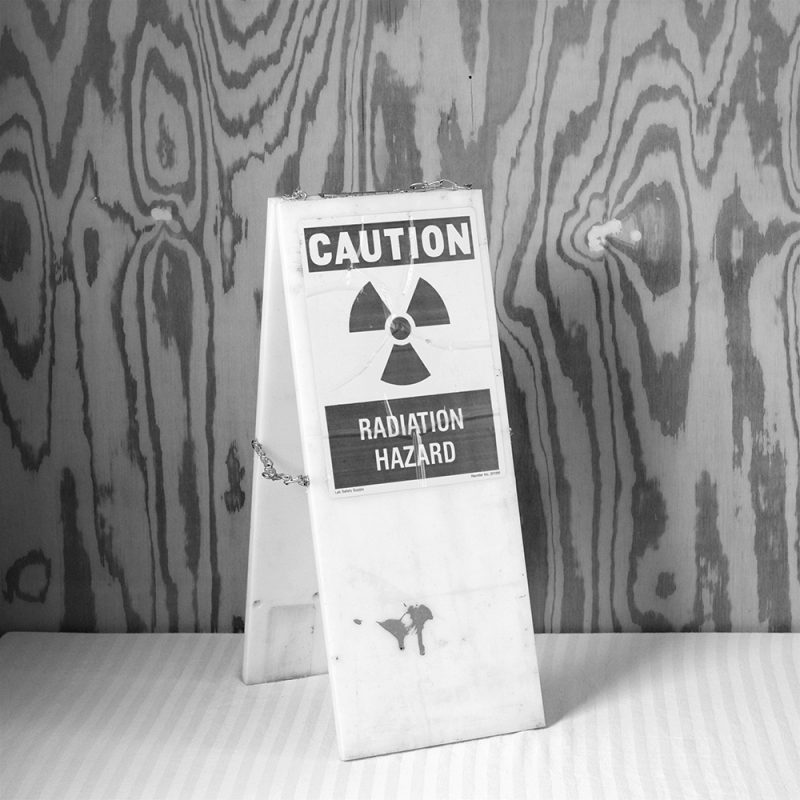

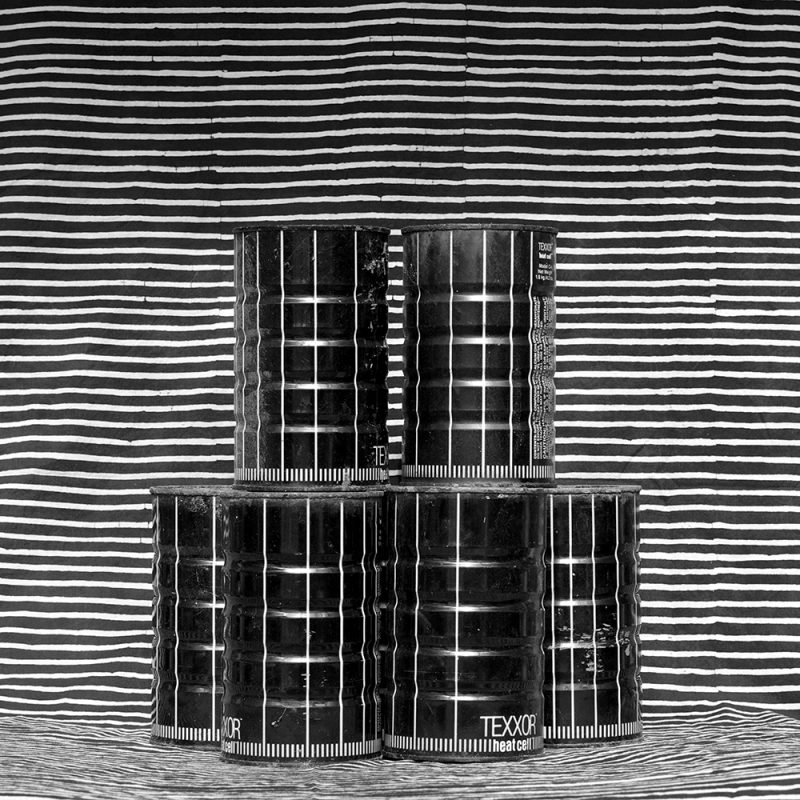

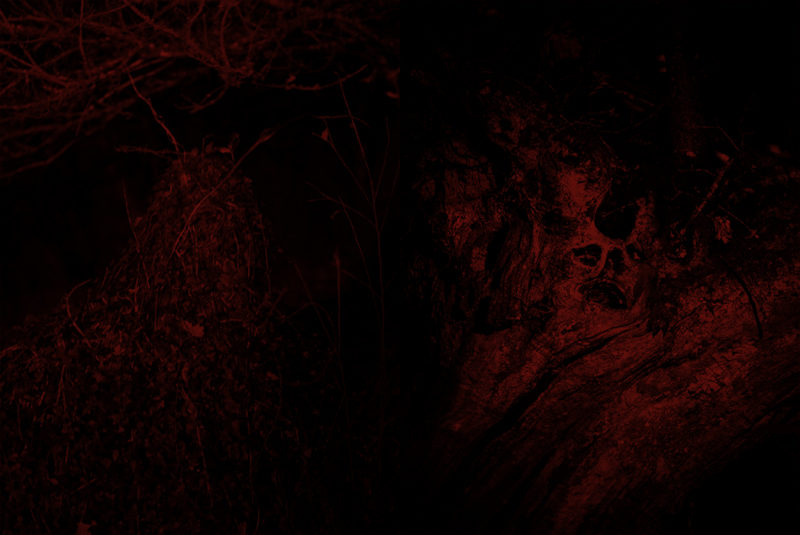

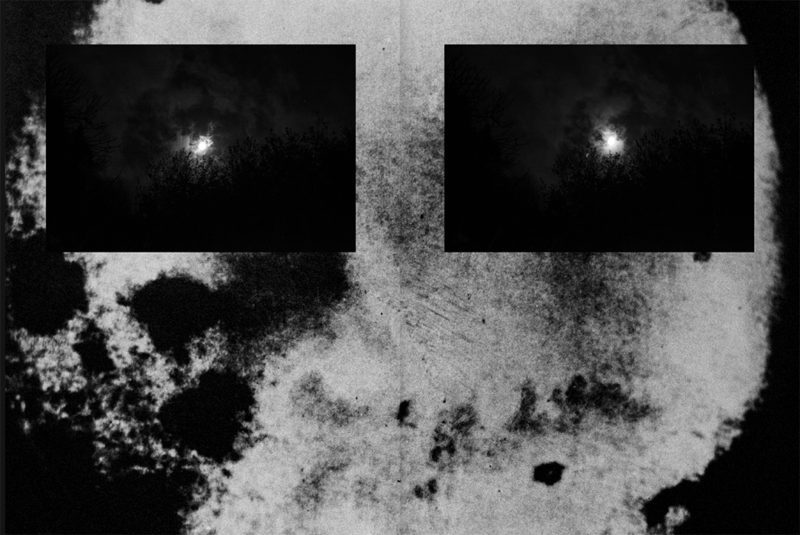

Following Ed’s archive and a collection of his correspondence, during which time we come to know and befriend him, we are presented for the first time with a series of Nájera’s own images. The Black Hole – so named because “everything seemed to go in but very little ever left” – was the shop Ed ran and curated. It sold assorted surplus material from the Los Alamos National Laboratory and acted as the hub of his political campaigning. After Ed’s death in 2009, no longer tended to with his obsessive care, the shop closed down and a sale occurred, designed to ensure that “as much stock as possible was owned by members of the community rather than being sold as scrap”. The Black Hole was a record of Ed’s meticulous attention to the cause, a rescuing of the materials that surrounded and populated his work; it was the physical embodiment of his enduring fixation. Nájera’s photo series documents a selection of these strange objects and materials, mostly unintelligible to the layperson when seen uncaptioned: gadgets and gewgaws with protruding wires, some sinister with symbols warning hazard, some seemingly benign (a box of phone handsets, books, a stack of graphite bricks).

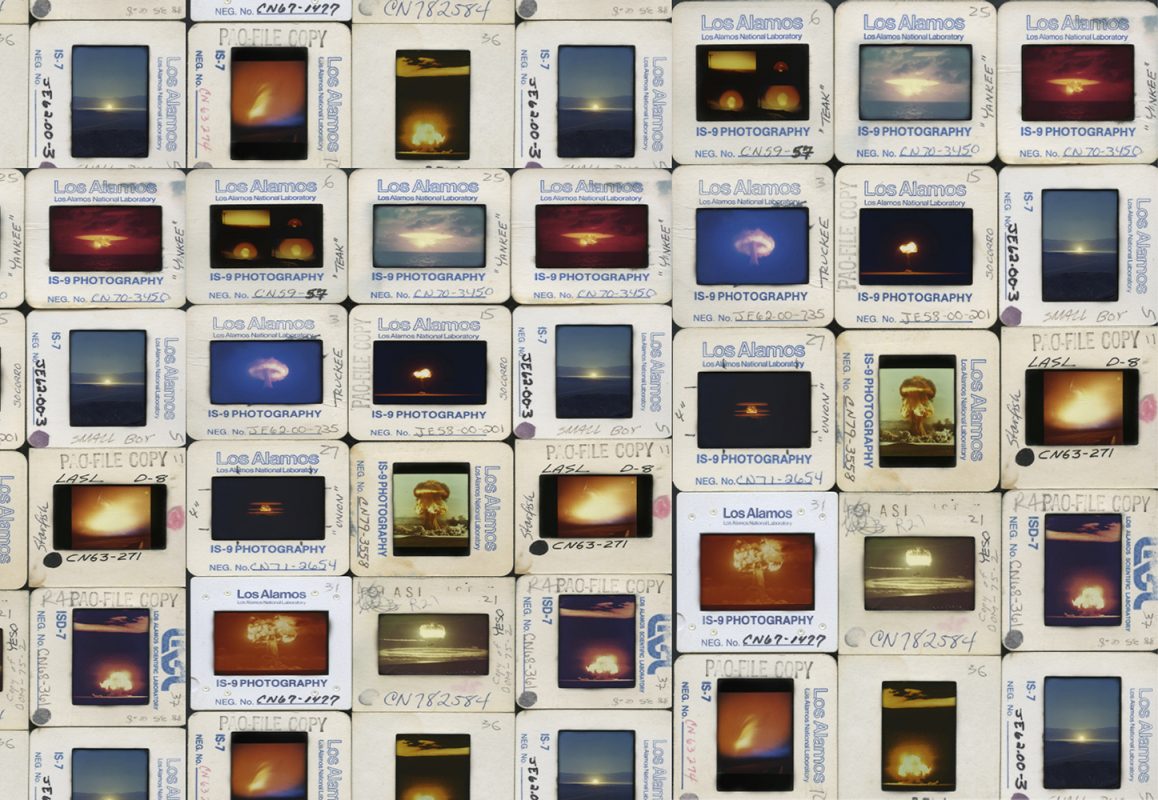

The Grothus archive as arranged by Nájera is engaging and visually appealing. The vivid colours of childhood snaps counterpose uncomfortably beautiful photographs of bombs bursting on desert plains: a burst of white gold in the centre of a blue-tinged dawn sandscape, the billowing orange bouquet of a mushroom cloud, each enlarged from slides taken from the Los Alamos lab documentation of bomb tests and trials. The rhythm established is one of ordinary life running alongside immense powers of destruction, a precarious coexistence that is rarely confronted in the everyday. Running through this uneasy admixture of imagery is Ed’s voice, via the telegrams and letters he sent, at times righteous and rageful — “Stop waging war. Stop your stupid war.” — and at others hopeful: “We cannot put the genie back into the bottle but with abolition of nuclear bombs we could all be certain of a future”. The voice that emerges is chipper yet obstinate, that of a sincere person fired up by a cause. It is striking, then, following the warmth and energy of the letters and family snapshots, that Nájera’s still lives are so austere: photographed in stark black and white, against plain monochromatic backdrops, and removed from context so that the objects she portrays seem baldly alien. Like the atomic advice leaflet that acts as a kind of prologue, it bookends Ed’s archive with the foreboding nature of its theme, that of atomic capability, which in fact — of course — has not dissipated: we live in a world where countries consider it necessary to retain nuclear power for the morbid quasi-reassurance of mutually assured destruction, should it come to that.

It is refreshing to meet with a work so free of ego in a photographic landscape that, at times, feels increasingly preoccupied with ideas of authorship. The recontextualisation of an archive allows a pile of letters to become a work of art, and even of friendship: we feel the anger and resistance and determination of a person dedicated to a vast cause that didn’t dissipate after the administration of a particular ‘president’ or with the end of a war, but that was ongoing throughout his life, though the acuteness of its threat shifted and transformed. Nájera’s particular achievement with the archive is to draw out this determination at the same time as Ed’s winking sense of humour and charisma. It is this extraordinary levity in his dealings with such a doom-laden subject that makes Ed’s archive so beguiling: his rightful rage is tempered by the velvet glove of his sarcasm and flashing grin. A 1973 telegram to Nixon, for example: “I think it is so very nice that you won’t be able to kill, bomb, burn and destroy beyond August 15th.”

At the time of writing, London’s roads have been blockaded for several days by the Extinction Rebellion. Commuters have been incensed by the inconvenience. Media discussion of the protests veers between the urgent and the hopeless. (Ed was aware of climate threat, too: he said that “a solution to the energy problem, so necessary for survival after the easy energy has been consumed should become a widely, freely, and ardently discussed issue here in Los Alamos.”) It is, of course, impossible to quantify the impact of a single campaigner or campaign on colossal issues like climate change or atomic capability, but Ed’s case is instructive: agitating for a better life while not seeing immediate results does not have to be disillusioning, but instead can be a lifelong attitude. Refusal to kowtow to the status quo can be both fierce and joyful. In the portraits of Ed that feature in the book he is, invariably, smiling, white-haired and with a twinkle in his eye; his desk strewn with books, his shelves packed with atomic detritus, and in front of him, a sign that reads “The legendary ED GROTHUS.” ♦

All images courtesy of the artist and Editorial RM. © Janire Nájera

—

Alice Zoo is a photographer and writer based in London, working with national and international publications such as BBC News, the British Journal of Photography, and the Washington Post. She is also a freelance photo editor at the FT Weekend Magazine, and co-founder of Interloper magazine.