Arpita Shah

Nalini (ongoing)

Essay by Emilia Terracciano

Arpita Shah’s Nalini is an ongoing photographic series about migration, memory and loss. From the ancient Sanskrit, Nalini, meaning ‘lotus plant’, conjures the gendered virtues of purity, fertility, and ‘spontaneous generation’. It is a popular Hindu name for girls.

Shah, who was born in Ahmedabad, Gujarat (India), raised in Saudi Arabia, and is now based in Scotland, has often used the rich and colourful pantheon of Hindu iconography to reflect on diaspora and issues of hybridity. Her playful series Nymphaeaceae, involving Asian, African and Arab women, explored issues of gender role play in Scottish studios. Shot across scattered times and geographies, Nalini moves away from the studio and the more reserved, conventional (perhaps stiffer) models of femininity we associate with this confined space, to focus on the lives of three women defined by migration: Shah’s grandmother, from which the series takes its name, her mother, and herself – although we never see her face.

An intimate representation of female dislocation, this evocative project is also fraught with anxiety as it seeks to piece together uprooted identities and social worlds variously inhabited by the three women. Photography occasions a series of spaces – carefully choreographed by Shah – in which lives and memories are recovered, celebrated, sometimes mourned. Loss, maternity and the longing for contact are constant tropes. We see flowers, textiles, skin, hair. Close-ups and tight framing heighten the tactile lure of Shah’s saturated surfaces. We are shown a flamboyant cascade of a magenta bougainvillea in full bloom, a mass of raven black hair, the moist wrinkles of Nalini who emerges from a bathtub. Rigorously uncaptioned, the fluid juxtaposition of these sensuous subjects suggests that to freeze, literally through the frame of the camera, a woman’s life in a single stage – as a grandmother, mother or daughter – is limiting – particularly taking into account the body’s centrality in feminist theory.

Shah has perhaps as much in mind when she selects a ruby pomegranate (a symbol also associated with fertility by the Persians) and the crumpled leaf of a lotus recoiled onto itself (a reference to Tantrism in which the lotus leaf is equated with the womb). Fertility and its decline are evoked in a ludic manner by Shah who anthropomorphises the vegetal realm to reflect on femininity. In another photograph, her camera focuses the folds of a sumptuous sari threaded with gold and silver brocade (it was ‘passed down through generations and made somewhere in East Africa’ Shah muses). When worn, the patli of a sari is hand-gathered into even pleats below the navel to create a graceful, decorative effect like the petals of a lotus flower – ‘almost like another skin’ – by great-grandmother, grandmother, mother and now by Shah herself. But Shah offsets the romanticising of sartorial customs with an horrific image displaying the effects that such feminine, domestic propriety can effect on a working woman: we see a pair of legs covered with severe scar burns. ‘My grandmother [Nalini] was making chapatis and her sari caught fire’, Shah writes.

For the young Nalini, leaving Nairobi, Kenya (the successful family ‘Krishna Dairy’ farm was sold after a series of riots in 1930) to relocate to Ahmedabad, Gujarat, meant renouncing a lavish lifestyle: not only her bougainvillea trees but perhaps also the aid of domestic workers, including a nanny, gardeners, maids and cooks. Such critical revisiting of femininity and the work of migration on the part of Shah tackles gardening as an art of memory – one that can imply subtle forms of feminine resistance.

To domesticate nature is also to become domesticated by it and we know that the transplant of native species to alien lands did aid newly-settled colonists, to create the ‘familiar’ and feel closer to home. One thinks of the grafting of the English landscape onto the Caribbean islands or the creation of Kew Gardens, London. But transplanting produces strange and hybrid landscapes, and Shah recalls how her father dug up concrete from the communal area to build an Indian rose garden in Saudi Arabia.

Processes of botanical appropriation also point to larger fights over bio-economies. Nalini, perhaps inadvertently, connects a faded photograph of the ‘Krishna Dairy’ with its proud, male staff and polished, motorised vehicles in full display, to an asphalt road cutting across what once was a luxuriant forest. Forms of extractive capitalism and the colonisation of natural resources go hand in hand.

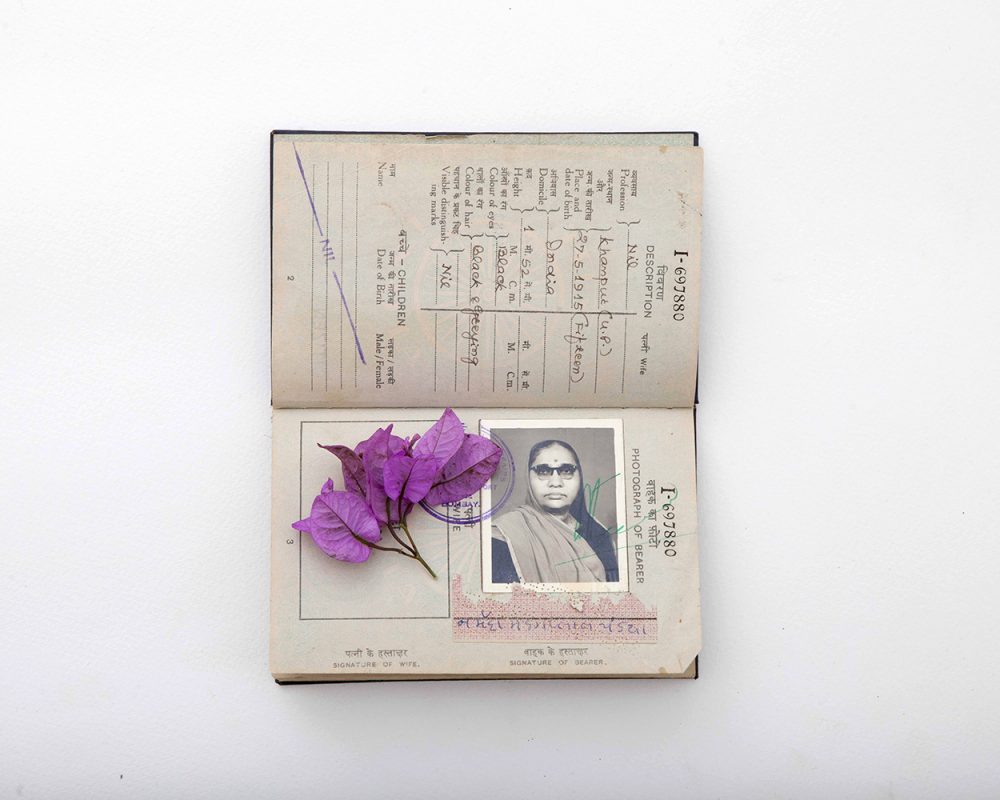

Shah collates her own herbarium and performs offerings in the form of flowers to Nalini and her mother. Cuttings picked in Africa, India and Europe adorn images mined from old family albums. In one instance she pays homage to her great grandmother by placing bougainvillea flowers alongside her passport photograph. The theatrics of flower offerings (puja in Hindi, also meaning ‘flower sacrifices’) evoke common Hindu practices of collecting and displaying photos of ancestors. In Indian homes, photographs, footprints and names written in books abound and are treated as more durable and tactile means to re-connect with ancestors – especially the deceased.

Printed photographs, notwithstanding the advent of digital imagery, have become increasingly popular over the years so that family members obtain pictures of their elders before they pass away. Framed and placed on domestic, makeshift altars, such portraits are beautified with locally-sourced flower garlands such as marigold and jasmine. Something of the kind is at work in Shah’s images and her hybridised forms of botanical offerings. This impulse to recover and gather old photographs and flowers could be read as a collection of intimate, small and impromptu portable shrines made by Shah on her wanderings across continents. In one final image, she crowns Nalini’s cropped silver plait with wild Kenyan pink roses, which signals the loss of fertility in Hindu custom. Shah figures the desire for diaspora through her photography, linking disparate spatial domains to extend lineage beyond the transient memories of living family members. Photography offers a trans-generational space, at once playful and performative, to rework forms of image-worship, rearrange flowers and memorialise the scattered, hybrid forms of the feminine. Nalini…what’s in a name? ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Arpita Shah

Nalini is supported by Creative Scotland and is being produced for an exhibition at Street Level Photoworks in February 2019.

—

Emilia Terracciano is an academic and writer based in London and Oxford. She is a postdoctoral Leverhulme Fellow at Ruskin School of Art, Oxford, where she teaches the course Globalisation, Photography and the Documentary Turn. Her research interests lie in modern visual art and photographic practices with a focus on the Global South. Her book Art and Emergency: Modernism in Twentieth-Century India was published by I.B. Tauris in November 2017. Emilia also writes for The Caravan, Modern Painters and Frieze.